Welcome to this most recent master class on dissociative co-existence. Jonathan Glazer’s latest film, “The Zone of Interest,” needs no lengthy explanation beyond its extended introductory blackout. As the longest-serving commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp, the wartime life of Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel) was portrayed via a fusion of a 2014 Martin Amis novel and Nazi military events. He and his family live in a functional but tastefully decorated compound directly adjacent to the camp, with a concrete, barbed-wire barrier next to their obsessively manicured garden, with the woods and river on the other side of their property. The film’s title refers to that term, which is applied to the Auschwitz perimeter area.

As such, this dividing wall also assumes the role of a leading character, given that much of the film involves seeing the billowing smoke from the crematoria, as well as hearing the (often, but not always, faint) screams and gunfire. And this is precisely the point, as life in the Höss household (with his wife Hedwig (Sandra Hüller), five children, and assorted servants) playfully goes on without any bother from the unspeakable mayhem next door. Later in the film, Höss gets a transfer, much to the dismay of his wife, who is so invested in being the self-anointed Queen of Auschwitz that she successfully gets Rudolf to stay in their home while he is working in the Berlin area.

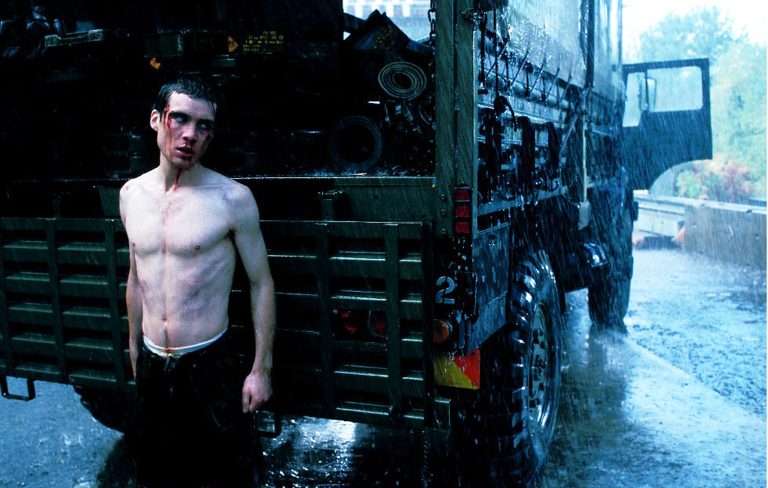

Prospective viewers should be aware of both the slow pacing and the spartan storyline, but its quiet symbolism and imperceptible gestures never fail to interrupt our full concentration. This is cinema that is hands-down required viewing for any student of the Holocaust or other serious filmgoers of any stylistic persuasion. With that said, the British director Glazer has not been prolific. “Sexy Beast” (2000) was his first full-length feature film, with “Birth” (2004) and “Under the Skin” (2013) to follow. This reviewer has quite frankly not enjoyed any of his previous films, finding his choices of creepy, quirky drama too contrived and simply unappealing. However, his earlier use of sound and ominous imagery were precursors of better work that lay ahead.

So what if the plot remains thin? “The Zone of Interest” remains an outrageously chilling production that is driven by its oblique referencing to what is happening mere feet away. There are lapses in Hedwig’s indifference with occasional snippets of sadism, where she lets a house servant know, in no uncertain terms, and at any time of her choosing, she could have her reduced to ashes. In contrast to the otherwise dominant bright green daylight shots of the Höss residence and its bucolic countryside environs, we see vivid, even if fleeting, nocturnal forays where a Judy Garland/Dorothy lookalike traipses through the muddy, burnt-out hellscape via black-and-white negative photography.

And to add an exclamation point, there is a cross-cutting of Daddy Höss doing his kids’ bedtime reading of the grisly Hansel and Gretel … just another dagger to the heart. We now have our most definitive proof to date that Dorothy is not in Kansas anymore. Turning the other cheek, being oblivious, complacent, or whatever, does not necessarily produce groundbreaking material, even when there are consequences of immeasurably mortal proportions. We’ve seen this before. However, when the stunning tranquility of the Auschwitz surroundings lay immediately next to the inferno itself, there is a precipitated reaction of combined fear, along with a very troubling inward gaze at ourselves. The Höss family looks like us, talks like us, and may just be us.

Contrasting themes are certainly no strangers in cinema, literature, and the arts in general. Beauty and tragedy are frequent travel companions, lest we also not forget that id and superego often reside within the same zip code. The aforementioned garden owes its fragrance, as well as the lifeforce of its many colorful species, to the fertilizer ashes. When Hedwig’s mother comes for a visit, she is proud that her daughter has elevated her own humble family origins to a more regal station. However, at night, we see her lying in bed, sleepless from the menacing orange glow, with her surreptitious exit from her daughter’s compound happening soon thereafter.

After finding a small piece of human debris in the nearby river, Rudolf hurries his children back to shore, and we next see black ash being rinsed off in the white porcelain sink back at the house. The film has a segment later during his assignment away from Auschwitz. In one scene, we see Rudolf attending a senior officer ball, replete with elegant chandelier lighting, that is juxtaposed against later witnessing him vomiting alone in a nearby dark stairwell. Could it be that he has begun to internalize his nightmarish duties, or is it related to an earlier scene where he is having an abdominal examination by his military doctor? Please credit Jonathan Glazer for keeping us guessing.

Terrence Malick’s 2019 “A Hidden Life” might be considered the flip side of an atypical Holocaust duet, where, quite similar to “The Zone of Interest,” Jews remain offscreen, and the carnage is kept at arm’s length. Instead, both films dwell on the inner psychic geography of either those involved or those who elect not to be involved. Regarding the act of not signing on, “A Hidden Life” is based upon the true story of Franz Jägerstätter, who was a Catholic Austrian village farmer and a conscientious objector, eventually sentenced to death for his refusal to pledge his allegiance to the Führer.

With its lush alpine dreamscapes, as seen through myriad camera angles and lighting/seasonal variations that are classic Malickian trademarks, Franz and his family may live high above the clouds but not heavenly enough to evade penetrance from the horrors beneath. This is not necessarily the most watchable film after the first forty-five minutes because the final three-quarters of this three-hour film is mostly consumed with highly repetitive torture and trials. Aside from its sole devotion to Franz and his progressive prosecution, “A Hidden Life” does not contain other atrocities, but there is archival footage of speeches, rolling tanks, and flags during the very first frames of the film. Either way, this first forty-five-minute segment is a must-see treatise on moral choice.

Although Franz never wavers in his resolve, we follow his journey in speaking to other villagers whose sporadic sympathy is only expressed in whispers and hushed tones, thus serving as a companion theme of hollow disengagement, just like in “The Zone of Interest.” His priest and then his local bishop urge Franz to both acknowledge the consequences of his decision, as well as the importance of honoring the Fatherland (noting, however, that the historical record underscores the conflicts between Nazism and Catholicism). Soon thereafter, Franz wanders alone into his chapel, sits down, and perhaps he finds some solace in the reflections of the emotionally beleaguered mural painter:

“I paint the tombs of the prophets

I help people look up from those pews and dream

They look up, and they imagine if they lived in Christ’s time, they wouldn’t have done what the others did

They would have murdered those that they now adore …

What we do is just create sympathy

We create admirers …

They won’t fight the truth

They’ll just ignore it.”

After you see “The Zone of Interest,” these words will be even more devastating when we realize how much the painter’s plea never seems outdated. Has our epidemic of excessive adoration irreversibly disrupted our rightful habitat of measured appreciation and balanced judgment? Please say it isn’t so.