Before his untimely death in 2007, Edward Yang was arguably the world’s greatest filmmaker: an artist with the patience of a great novelist and the vision of a master painter. Of all the directors to emerge from the New Taiwan Cinema of the 1980s and ‘90s, his star shone brightest.

It started out humbly enough, with some TV movies and a contribution to the seminal anthology film In Our Time (1982). His first two features – That Day on the Beach (83) and Taipei Story (85) – were touching tales of wasted youth and urban malaise, but it was Terrorizers in 1986 that he first flirted with the transcendent. A shrewd update on Antonioni’s Blow-Up, the film’s postmodern storytelling flits between different characters with a rhythm all its own. Yang never looked back, and the next twenty years would comprise a practically perfect run of films, including two expansive, gorgeous masterpieces whose reputation grows year after year.

As new restorations of his output tours American theatres, now is as good a time as any to reflect on the oeuvre of a singular genius of the silver screen. For Yang, the camera was a gift with which he could make poignant insights into the human condition that few have rivaled before or since. The only shame is that he didn’t have more time to express himself.

7. That Day, on the Beach (1983)

By all accounts, That Day, on the Beach is an engrossing example of New Taiwan Cinema, a drama whose contrasting of the rural and urbane exemplifies many of the movement’s key themes. It follows two women – one played by future director Sylvia Chang – who were friends during childhood but now have very different approaches to life. Told in an elliptical structure that flashes back and forth, the story unfurls with such satisfaction due to the layered characterizations at its core, anchored by excellent performances across the board. Interestingly, the film marks the only collaboration between Yang and visionary Australian cinematographer Christopher Doyle, later a frequent Wong Kar-Wai collaborator. His impeccable command of shadow and light is already on full display here.

That the film is Yang’s least accomplished work is a testament to his track record in later years more than a slight on the movie. Compared to Yi Yi or A Brighter Summer Day, That Day, on the Beach finds it harder to justify its expansive runtime (144 minutes), and the overlaps between the women’s stories can make the narrative feel a bit repetitive. Nevertheless, for those inexperienced with Yang’s oeuvre, the beginning may be the best place to start, allowing you to enjoy the pleasure of seeing the director’s skills as a filmmaker develop with each passing year. In any discussion of early New Taiwan Cinema, this film should get a mention.

6. Mahjong (1996)

Mahjong leaps off the screen with a contagious energy that arguably makes it the Black Sheep of Yang’s career. However, a departure from the norm can sometimes be uniquely refreshing, as this crime caper indeed is. Like A Confucian Confusion, made two years before, the film is something of a genre experiment that dissects the East-West divide in Hong Kong, this time in the criminal underworld, spearheaded by a genuinely funny performance from British actor Nick Erickson in a role initially slated for David Thewlis. Rather than appearing as a plea for crossover appeal, the film’s melting pot of genre, culture, ideas, and languages works to reflect Taipei’s underbelly in all its unkempt, enthralling glory.

The movie takes a little while to warm up, but by the climax, you’re on the edge of your seat. Again, the architecture of Taipei provides the backdrop for some excellent lived-in world-building. Yang’s use of recurring locations to geographically place a story in a city and time is one of his greatest assets. It means he’s able to engross the viewer in either a heartbreaking existential drama or something more playful. To pun on the movie’s title, the gamble certainly paid off on this one.

5. Taipei Story (1985)

Western distributors renamed Yang’s second feature to evoke the legacy of Ozu’s classic Tokyo Story, and the echoes of Japanese domestic drama certainly reverberate throughout. Similar to Ozu’s best films, it’s another thoughtful take on shifting cultural values. The 1980s were a decade when unprecedented periods of economic growth resulted in seismic social change, particularly in regard to the class system and the battle of the sexes. In Taipei Story, protagonist Chin is an archetypal career woman at an architecture firm playing a very literal role in the city’s construction and largesse, whilst Lung (played by Yang’s friend and fellow filmmaker Hou Hsiao-hsien) is a faded minor league baseball star who can’t hold down a job. As childhood sweethearts, they have seen their relationship drift apart in real-time as the power balance changes drastically between them.

The film also ranks among the most aesthetically pleasing entries into Yang’s filmography. The neon-soaked cityscapes of Taipei have never looked prettier or more foreboding. The portrayal of the city’s boxy, claustrophobic architecture is particularly pertinent, a fine example of Yang’s visual flare being used to complement the narrative rather than an ornamental distraction. The result is something that’s perhaps too sobering to watch over and over but undeniably captivating as a precise snapshot of a time in place of a country in transition, as reflected beautifully in a melancholy tale of a woman trying her hardest to leave the past behind. The tussle between past and present, modernization and tradition, masculine and feminine, all under Yang’s watchful eye and deft touch.

4. A Confucian Confusion (1994)

A Confucian Confusion is the most critically underrated film in Yang’s back catalog, a shrewdly written and bitterly cynical comedy of manners depicting Taiwan’s burgeoning leisure class. The movie also demonstrates the director’s most forthright conversation with contemporary youth: most of the characters here are under 30 and struggling to reconcile hedonism with the professional restraints of corporate Taiwan. The catchy title stems from a particularly revealing plot point about an author who pitches a book where Confucius returns to modern Taipei; whilst many are taken in by him, it’s only so they can ask how he manages such a convincing disguise.

Yang suggests that in a decade as fraught with political tension as it was with economic growth, the values of Confucius’ China and the West are fundamentally at odds. Taiwan sits at a unique crossroads between the East and West, and as the situation there escalates, this film is sadly more relevant than ever in examining this fact.

Perhaps the biggest drawback to A Confucian Confusion’s popularity is the hitherto poor video quality of any available copy in the West, but recent restoration efforts by Janus Films promise to solve this. What has always been apparent is the ingenious screenplay, which accomplishes the rare feat of creating layered, vulnerable characters within a comic setting. The dialogue melds wordplay and wry observation with moments of heartfelt sincerity, especially an ending that offers an optimistic view of a way forward for Taiwan’s youth despite all.

3. Yi Yi (2000)

Yang’s died in 2007, but his struggle with cancer had been ongoing since the turn of the millennium. Perhaps it’s post-rational thinking to view his final film, Yi Yi, in that context, but from its very first frame, it is a movie fascinated by the very fibers of human life, the everyday moments of a year in the life bookended by two of its greatest ceremonies – a wedding and a funeral. It is as beautiful a swan song as any filmmaker has achieved, a worthy recipient of overwhelming critical acclaim upon its release, and now solidly within the pantheon of the great films of the 21st century.

Do not be daunted by this reputation, though. Yi Yi remains perhaps the most instantly accessible and rewarding entry in Yang’s filmography, quickly finding a groove in its editing and cinematography, which makes life’s minor moments seem grandiose because, to this director, they are. Leisurely but justified pacing allows the introduction of over a dozen recognizable characters, each with different motivations and personal weaknesses. The extent to which an individual must overcome their faults seems to be a focus here, including whether faults can really be overcome at all.

Perhaps, as humans, the best thing we can do is embrace our differences and limitations and try to fulfill our desires with the help of those around us. If ‘life is beautiful’ feels like too broad a stroke for a compelling film, then rest assured, the typically painterly detail with which Yang paints this panorama of modern Taipei fills in the blanks and should enlighten even the most cynical of viewers.

2. Terrorizers (1986)

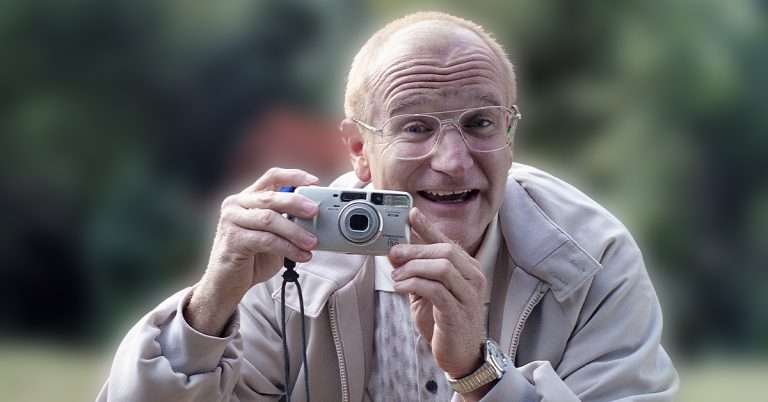

As alluded to in this article’s introduction, Terrorizers was the first time Yang was able to reach into the transcendent, the first time he made a film whose true brilliance cannot be described in words. From a certain point of view, this is a shrewd post-postmodern take on Antonioni’s Blow-Up, another film about a photographer who uncovers a world of mystery in their negatives, but that’s just one of many strings to the movie’s bow. Throw into the mix a compelling domestic drama (à la Taipei Story), a gripping gangster drama, and an unconventional narrative structure, and you get one of the most unique films of the ‘80s.

There’s just a tangible and luxurious command of craft on display, and now that Yang has mastered his medium, he can deploy its tricks with a wanton playfulness. The overlapping stories and subtle flirtations with surrealism make the film a real puzzle box, a jigsaw in which all pieces must be in place in the viewers’ minds to make any sense of it all. But perhaps the greatest praise I can give Terrorizers is that one does not need to fully comprehend the intricacies of the plot to understand and appreciate it: Yang’s elegance behind the camera and array of strong performances in front of it make it a viscerally emotional, rather than restrictively intellectual, experience. A cerebral slice of social commentary whose experiments with genre leap off the screen, Terrorizers is a seminal turning point in Yang’s career and can stand toe-to-toe with his more famous later efforts.

1. A Brighter Summer Day (1991)

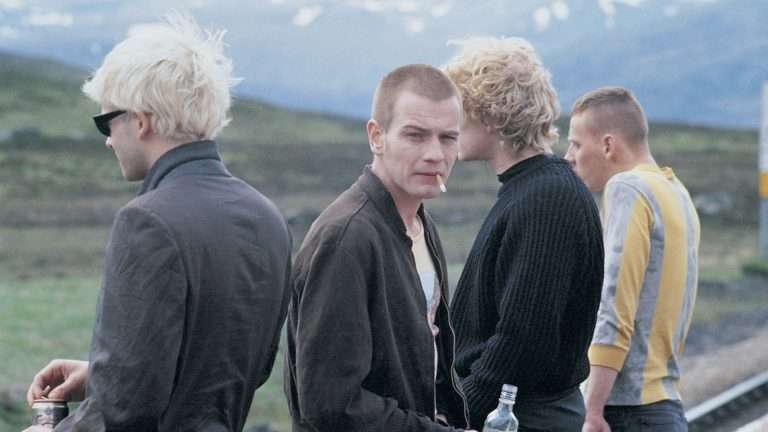

Despite its four-hour runtime, A Brighter Summer Day is, in one sense, Yang’s giant swing for the fences, a prestige drama with worthy themes and an expansive cast of almost 1000 extras. If this film was American, you could imagine it sweeping the Academy Awards. Still, its current incarnation has been a hidden gem for film buffs and restoration experts to uncover over the years. The current Blu-ray copy, compiled from various prints, is a miracle of modern cinema in allowing the world to experience this beautifully warm and humane masterpiece, a reflection on youth and love and violence that feels both hopeful about the future and angry about the present.

The film is ostensibly a coming-of-age story set in the 1950s about Xiao Sir, a boy struggling to become a man amid pressures from his home life, school, and the youth gangs that infest the streets. His prospective girlfriend, Ming, provides respite from his troubles, but their moments of affection bring further complications to their lives, leading to a heartbreaking climax. The magic of the picture is the lengths to which Yang and his collaborators go to make Xiao Sir’s world feel authentically lived in, a feat in production and costume design as much as pitch-perfect casting and patient pacing.

The viewer can’t help but build an unbreakable empathy for the young man despite his faults; his concerns become our concerns, making the ending all the more difficult to watch. But watch it, we must, and re-watch and re-watch, because the lessons told within this masterpiece will be worthwhile until the end of time, a fitting way to complete this ranking and pay homage to a mighty magnum opus of world cinema.