While most movie lovers are well-versed in the French New Wave, far fewer are aware of the cinematic movement that arose in the little island country of Taiwan across the closing decades of the 20th century. The Taiwan New Wave has its origins in a series of reforms and personnel changes made to the Central Motion Picture Corporation (CMCP) in Taiwan in the early 80s, which revolutionized the landscape of cinematic production across the nation. The changes came after Taiwanese cinema had been saturated for nearly two decades with escapist entertainment-oriented films, from cheap rom-coms to Hong Kong-style formulaic martial arts movies, and the time was ripe for breaking away from conventions and trying something new. Inspired by the neorealist movements in European cinema, Taiwanese filmmakers started experimenting with a realism-based approach with slim budgets and non-professional actors (often casting their friends and family).

The ambition was twofold: to produce a new breed of cinema focused on documenting the minutiae of everyday life in a rapidly urbanizing Taiwan and to consolidate a collective national memory on film by narrativizing Taiwanese history. These twin tendencies can be seen represented by the two greatest luminaries of the Wave, who have garnered the most international acclaim, namely Edward Yang and Hou Hsiao-Hsien. While Yang’s films have primarily tended to focus on urban lives and the accompanying sense of alienation, Hou’s most prominent works are typically rural-set, focusing on the lives and memories of Taiwanese natives, which refract national history. New Taiwanese Cinema titles are distinctive for their formal minimalism and a keen interest in socio-cultural commentary, and the movement has produced a treasure trove of films and filmmakers that stand the test of time.

In this list, we look at ten great films from the Taiwan New Wave, all of them essential watches for anyone looking to acquaint themselves with the best that Taiwanese cinema has to offer–

1. In Our Time (1982)

In Our Time injected a breath of fresh air into the 1980s Taiwanese film industry, saturated with escapist action and melodramatic movies, and simultaneously paved the way for the New Taiwanese Cinema movement. Comprising an anthology of four stories that depict ordinary life in Taiwan, it marked the beginning of a neorealist approach to filmmaking in the country with its nuanced representation of social life and a focus on the naturalistic portrayal of emotions.

The first tale, “Little Dragonhead,” directed by Tao Te-Chen, focuses on a young boy seeking retreat within his dinosaur toys to shelter himself from the outside world, where he only faces constant bullying and rebukes from his parents. The second tale, “Expectations,” shifts to a young girl entering puberty who happens to develop an infatuation with their new tenant, a man much older than herself. Directed by Edward Yang, it focuses on the many expectations and hopes that fill her little head and how they affect the people in her life.

The third segment, titled “Leapfrog” and directed by Ko I-Chen, shows an enthusiastic college goer trying to stay afloat under the weight of his ambitions as he tries to organize a collegiate swimming competition, which he dreams of winning. And the final tale, “Say Your Name,” offers a humourous account of one morning in the life of a couple who accidentally get locked out of their home and workplace.

Directed by Yi Chang, it provides a fun and fascinating conclusion to these four tales of varying temperaments. Together, these four episodes represent a range of ages and moods: from the budding innocence of youth to the blooming possibilities of the early teens, the competitive headrush that characterizes a young adult, and the multifarious complications of marital life. They make for a vibrant scrutiny of humanity in all its shades, with the four scripts embodying rebellion, melancholy, perseverance, and, finally, just sheer bad luck.

2. Taipei Story (1985)

Much like the nation Taiwan trying to carve out its own economic and cultural identity separate from the Chinese mainland, the characters in Edward Yang’s Taipei Story seem to be stuck between the decadent clutches of the familiar past and the alluring, yet uncertain, promise of a future inspired by the West. The film is rooted in a sense of shifting timelessness that would come to define New Taiwanese Cinema in its attempts to move away from melodramatic escapism and into angst-ridden urban landscapes.

It stars fellow auteur Hou Hsiao-Hsien (who also co-wrote the script) as the emotionally distant Lung, a man content living with a stagnating measly job while basking in the glory days of his past spent playing baseball. His girlfriend Chin (Chin Tsai) is on the other end of the spectrum – assertive, ambitious, and dreaming of the bourgeois fantasy of climbing corporate ladders and living a life of material prosperity in the United States.

Chin can’t seem to convince Lung to let go of the ties that bind him to his homeland and his old friends and family, ties which also prevent him from soaring high by joining his brother in America as partners in a profitable business. This constant impatience with the old and decaying and the gradual embracement of the modern structures Yang’s dramatic vision, patiently upheld by his sensitive treatment of the characters.

The film features impeccable chiaroscuro lighting enveloping the frames with the soft warmth characteristic of the familial comfort offered by one’s hometown, contrasting it with the blazing neon signs brought about by capitalism and the inevitable cultural confluence with the West. Yang’s decision to cast his friend Hou and the fact that the latter sold his house to help fund his friend’s film aptly represent the homegrown independent spirit that came to define the Taiwan New Wave.

3. A Time to Live, A Time to Die (1985)

Inspired by the director’s experiences while growing up, A Time to Live, A Time to Die represented a noticeable leap forward within Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s filmography. A tale as melancholic as it is restrained, the film sees Hou coming into his own in terms of the formal and stylistic elements that would dominate his later work. It tells the story of a family leaving behind the Chinese mainland to settle in Taiwan and all the cultural and familial changes entailed by the shift. The protagonist Ah-ha (which also used to be Hou’s nickname) is a little kid sharing a deep bond with his grandma as his father dies while he’s still young. We see his grandma, growing old and senile, often abruptly setting forth to go back to their former home in mainland China, sometimes taking Ah-ha with her but always eventually coming back home.

As Ah-ha grows up to be a rebellious high-schooler, getting into fights and falling in love, there starts developing an emotional gap between him and his family, especially the grandma to whom he was so attached as a kid. A Time to Live, A Time to Die is the second film in Hou’s coming-of-age trilogy that begins with the seminal A Summer at Grandpa’s (1984) and closes with Dust in the Wind (1986).

As a sensitive tale about growing up among street gangs, family woes, and the uncertain promises of the future, the overall portrayal of post-immigration life almost seems to foreshadow Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day (1991), which goes on to deal with similar themes in greater detail. The languidly paced narration (with a voiceover from Hou himself) ever-so-slowly creeps up on the viewer to an astonishingly powerful conclusion as bittersweet as life itself, tying together the many emotions scattered throughout its epic sweep.

4. Terrorizers (1986)

With his third feature, Terrorizers, Edward Yang casts a harsher eye on society and presents a drama that trades some of the warmth and organic intimacy of his previous work for cold and calculated cynicism. The gloomy note it begins with turns positively devastating by the end, signaling a broken society where the cracks run deeper than one might imagine. Terrorizers feature several lives within urban Taipei connected by what seems like sheer coincidence, with random acts of violence and mischief setting off butterfly effects that proceed to destroy their peaceful co-existence (or at least the illusion of it). The narrative is developed through a mosaic of perspectives: a young photographer’s voyeuristic forays into the urban life around him, a doctor from China’s rocky marriage to his novelist wife, and a rebellious teen hanging out with the local street gang.

The film occupies a peculiar place within Yang’s filmography, marking a turn into darker territories, with its violent nature seemingly a precursor to his much broader exploration of criminality in A Brighter Summer Day (1991). The way the film cuts between the multiple story arcs to forge narrative linkages and uses montage to embellish character details and plot progression is symptomatic of a maturing filmmaker starting to experiment with form to achieve narrative ingenuity. Yang maintains an almost Bressonian distance from his subjects, utilizing a style that doesn’t call attention to itself but rather quietly works its magic by dialing up the tension through stray observations, magnifying in significance as the story develops.

5. A City of Sadness (1989)

Charting the destruction of a family over years of political conflict, Hou Hsiao-Hsien presents one of the strongest films in his oeuvre by focusing on a harrowing point in Taiwanese history that nearly crippled its backbone. A City of Sadness spans between the years 1945 and 1949, and with Hou himself being born right in the middle of this period, his script is justifiably filled with the bitterness and anguish of his people struggling to eke out a peaceful coexistence. Taiwan had barely just achieved its independence from Japan when it was thrust into a civil war with the Kuomintang government (KMT) arriving from China. We see members of the Lin family getting torn apart, limb by limb, in a series of conflicts with the mainlanders amidst conspiracies and false accusations – all of it leading to a spike in violence and death across the city, cruelly justifying the title.

Like most works of New Taiwanese Cinema, A City of Sadness is preoccupied with depicting a people caught in transition, but of a kind that’s vastly different from the cultural transition to Western urbanity generally represented by other works in the movement. With steady, measured takes and Hou’s signature narrativizing that prioritizes empathy with the human condition above all else, the film transports the viewer to 1940s Taipei and lets them experience the fallout of political turmoil from the perspective of the common suffering citizen. The first of three films by Hou Hsiao-Hsien that depict Taiwanese history, A City of Sadness was the first film to openly represent the KMT’s abuses of power, including the infamous February 28 event. It was also the first Taiwanese film to win the Golden Lion at Venice and was responsible for bringing Taiwanese cinema to greater international attention.

6. A Brighter Summer Day (1991)

After making three features focusing on the impasses of contemporary urban life in Taiwan, Edward Yang was inspired by his peer Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s A City of Sadness (1989) to craft his version of the story of Chinese immigration to Taiwan following the Communist Party’s victory in the mainland. The result was A Brighter Summer Day, undoubtedly the most personal film in Yang’s career and probably the most comprehensive portrait of a nation and its people at a crucial juncture in its history.

It tells the coming-of-age story of Xiao Si’r (Chang Chen), a high-school student and the son of immigrants, struggling to balance his studies between getting embroiled in local gang wars and his love for a girl named Ming (Lisa Yang). His parents were forced to leave behind the familiarity and comfort of their past lives and quickly adapt to a foreign country, while their children grew up in an atmosphere of political unease and identity crises. Were they Chinese, or were they Taiwanese?

As Taiwan herself struggled to eke out its own national identity from the clutches of its neighboring governments, so did her young citizens. The film’s English title is a reference to a misheard lyric from Elvis Presley’s “Are You Lonesome Tonight?” and is emblematic of how the narrative represents the rapid modernization of Taiwan that was taking place, with an influx of American pop culture that allowed the youth to dream differently than their parents and also find a shared sense of belonging in popstars and rock n roll. With an engineer’s precision and an artist’s flair, Edward Yang ever so subtly hints at emotional developments without spelling them out and uses contrast over exposition to communicate his intentions to incredible effect in a sprawling epic of a film reportedly featuring over 100 speaking parts.

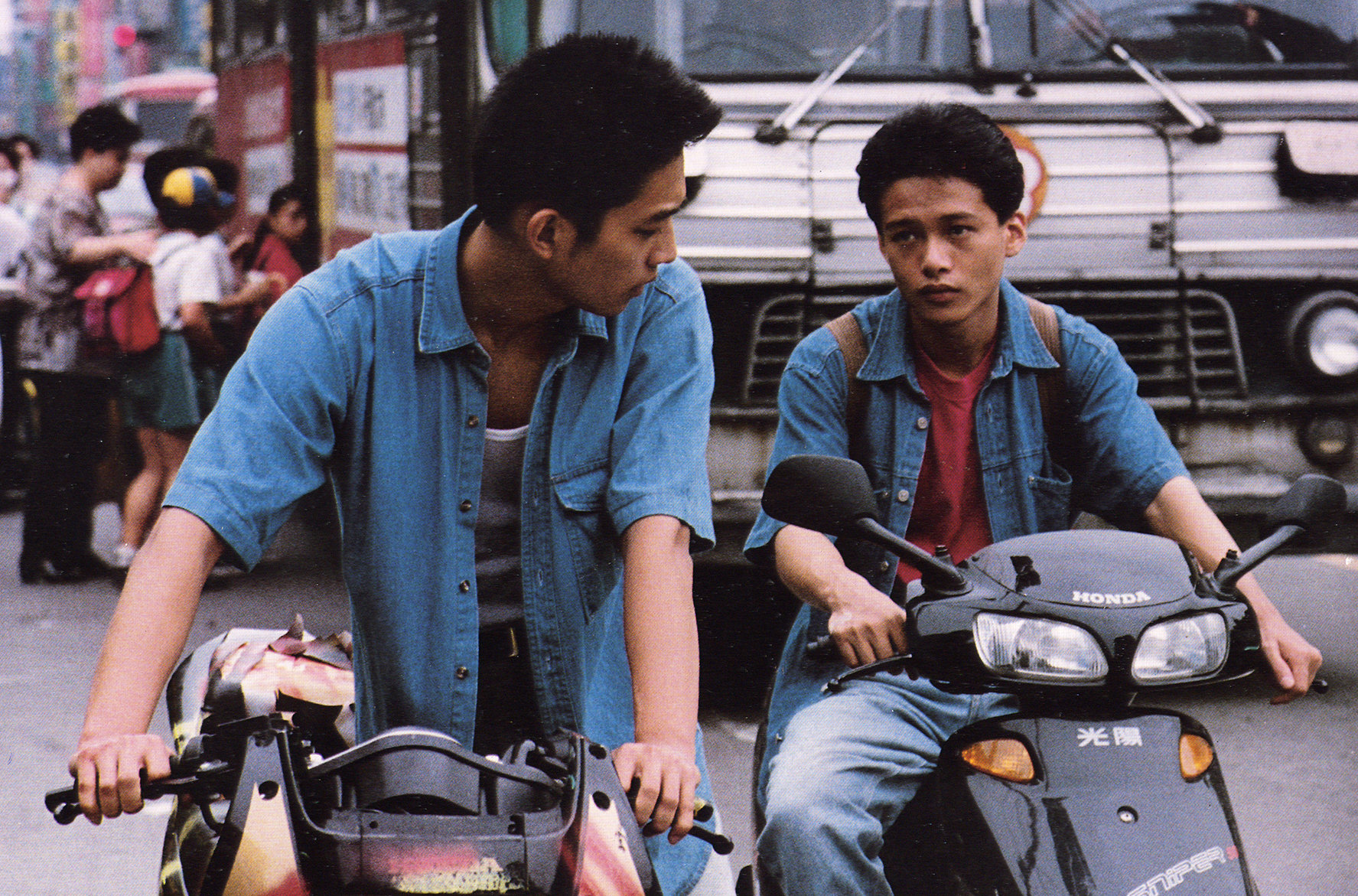

7. Rebels of the Neon God (1992)

Tsai Ming-Liang’s debut feature Rebels of the Neon God presents a poignant portrait of urban rootlessness and the heady cocktail of longing and isolation shaping the lives of teens and young adults in metro cities. The narrative primarily follows Hsiao-Kang (Lee Kang-Sheng), a teenager putting himself through cram school and living a drab life with his parents. A parallel storyline shows us Ah Tze (Chen Chao-Jung), who, with his friend Ping, leads an aimless life of petty delinquency punctuated by booze and women. The two arcs converge in a chance encounter when, one day, Hsiao-Kang is forced to get a lift to school in his father’s taxi after his motorbike is impounded. Tze, who’s on his bike, vandalizes the taxi’s side mirror and drives off, and Hsiao-Kang develops a strange and ambiguous fascination for Tze.

Hsiao-Kang soon quits his school and starts hanging out around Tze, hoping the latter notices and acknowledges him. This obsession soon takes on perverse forms, like when one day he vandalizes Tze’s motorbike and dances in joy as he watches the distraught Tze discovering his wrecked vehicle. The “Neon God” in the title is a reference to Nezha, a Chinese deity known for being impulsive and rebellious, with whom Hsiao-Kang seems to identify at least partially when he writes, “Nezha was here” on the sidewalk after trashing Tze’s bike. Rebels of the Neon God also marks the film debut of Lee Kang-Sheng, who goes on to become Tsai’s constant collaborator, appearing in all his subsequent feature films.

8. The Puppetmaster (1993)

The first film from Taiwan to compete at the prestigious Cannes Film Festival (where it bagged the Jury Prize), The Puppetmaster was Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s second film after A City of Sadness to extensively deal with Taiwanese history. It presents an endearing docudrama on the life of Taiwan’s most cherished puppeteer, Li Tian-Lu, who appears in the film as himself, having previously acted in Hou’s films as well. The film cuts between Li’s childhood and early adulthood when he had to use his puppetry skills to serve wartime propaganda, alongside snippets of Li in the present, looking back upon his life and times. It features several actual puppet shows, with the focus in each case shifting from the enacted scene to the puppeteer by the end.

Set across the first half of the 20th century, when Taiwan was still under Japanese occupation, The Puppetmaster depicts a time when traditions, rituals, superstitions, and fate seemed to overrule man’s attempts at carving out a life for himself. Something that Li himself says in the movie, “Man’s fortunes are unchangeable,” resonates hard when read alongside the catchphrase from the film’s poster, i.e., “There is always someone pulling the strings…”. Despite everything that these colonized Taiwanese natives are doing for themselves, they still seem to be reluctantly forced to dance to the tune of some higher power, guiding their destiny as if they were puppets themselves. Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s penchant for restrained elliptic storytelling reaches its zenith in The Puppetmaster, with the narrative being built around a series of ellipses – a structure that Hou borrows from traditional Chinese opera.

9. Vive L’Amour (1994)

They say, “Home is where the heart is,” and Tsai Ming-Liang’s second feature, Vive L’Amour, operates along similar lines while inverting its structure, showing that the absence of the heart is irrevocably linked to the absence of a home. May Lin (Yang Kuei-Mei) is a real estate agent who sells houses to other people but seemingly lacks a permanent place to stay, flitting between her workplace and the many apartments she has keys to. Her lover Ah-Jung (Chen Chao-Jung) illegally sells garments on the footpath and retreats to Lin’s apartment for his sexual proclivities. Hsiao-Kang (Lee Kang-Sheng), a columbarium salesman, steals Lin’s apartment key to let himself in when she’s absent. Despite his job being to arrange a resting place for other people in their afterlife, he seems to lack one himself.

The title, which translates to “Long Live Love,” is a farce: there is barely any love in the characters’ lives, and common lust is the most they can hope to experience. None of the three lonely individuals are shown to have a proper residence for themselves, inhabiting a common apartment, which also becomes the shared space where they carry out their futile search for intimacy and purpose, their personal identities abounding in irony.

Tsai never fully clarifies whether these people really are homeless or not, and, aptly, that information is never necessary to understand them. His portrayal of a cold and lonely Taipei emphasizes the absence of love within the lives of his characters and, thus, their efforts to find a true abode. The long static takes – still less extreme when compared to Tsai’s later work – and minimal framing highlight the alienation plaguing these urban lives and present a truly arresting portrait of three lives marginalized within their own social spheres.

10. Yi Yi (2000)

The final title on our list is Edward Yang’s last film, Yi Yi, a fitting swansong about life itself and a sweeping rendition of all the trials and tribulations constituting modern day-to-day existence. The film opens with the marriage of A-Di, brother to NJ (Wu Nien-Jen), whose family forms the centerpiece of Yang’s script. Other key players are also introduced through this grand gathering: NJ’s son Yang-Yang (Jonathan Chang) and elder daughter Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee), his ailing mother who falls sick during the wedding, and his former love interest Sherry, whom he meets after 30 years. NJ is a level-headed family man and a dutiful employee, but his past unexpectedly catches up with him and leaves him questioning his moral integrity through the events that follow.

Yi Yi observes three generations of a Taiwanese family, grappling with the many quandaries that inevitably arise with living in a material world made up of sobs, sniffles, and smiles, with sniffles predominating. Spaces merge within Yang’s frames through reflections on windowpanes and glass surfaces, sometimes blending in the urban backdrop with workplaces, homes, and cafés, much the same way that the characters’ lives collide and bleed into each other, affecting them in unforeseen ways. The evolving city is as much a part of their lives as they are a part of the urban revolution. Beginning with a wedding and closing with a funeral, Yi Yi comes full circle in its depiction of the cycles of birth and death, creation and destruction, coalition and dissolution that structure human existence.