Agnes Varda is primarily known for being one of the most important and recognizable names in the history of European Art Cinema. Some claim that her film La Pointe Courte (1958) was the true beginning of the French New Wave, many regard her study of time and existentialism in Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962) to be one of the greatest films in cinema’s history, films like One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977) and Documenteur (1981) are seen as landmarks in the study of femininity and her various documentaries have left her regarded as one of the most important and revered documentarians.

Agnes Varda is as significant for her progression in cinema as she is for her work in feminism, a landmark figure in both respects and at the convergence of the two, she is almost unchallenged in her often-cited title as the ‘Greatest Female Director of All Time’. This heavy praise and acclaim have meant that her films are largely circulated, repeatedly applauded, and have become cornerstones in the study of cinema. However, despite the large praise of these monumental works, there is a glaring gap in the study of Varda’s oeuvre – her short films.

Related to Agnes Varda – Faces Places [2017] – A Joyful and Wistful Journey of a Preeminent Artist

It is perhaps an oversight that befalls most great filmmakers – over the years, the study of cinema has often neglected short films, preferring to concentrate on feature-length productions. This can largely be attributed to economic issues and the perceived value for money for audiences (or lack thereof). Therefore, short films have often been disregarded (both in their creation and the exhibition of them) due to the lack of pull for audiences and the consequentially poor economic gains for cinemas. Yet, thanks to the advent of the internet, previously rare and underseen short films have seen a certain resurgence, with fans often being able to cheaply, or even freely, have access to these works. And, after uncovering Agnes Varda’s work in the short format, it is perhaps as good a reminder as any of the importance of recognizing short films and the ability they have in offering certain artistic visions and perspectives that are not so readily afforded by, or suited, to the longer form.

Not only do these works of Varda’s further emphasize her artistry, but they offer a level of experimentalism that often isn’t available in even the bravest of her feature-length films. These films frequently work by challenging conventions, reinventing cinematic forms, and introducing or critiquing concepts or ideas. For what they lose in the narrative structures and character creations evident in her feature-length films, they make up for in invention, wit, and cinematic intellectualism. While her feature films play out as novels, these short films play out as poems to the cinema, both challenging and affectionately recognizing the complexity of the medium.

L’OPERA MOUFFE (1958)

During her first pregnancy, Agnes Varda filmed Diary of a Pregnant Woman (1958). The film acts as an impressionistic portrayal of pregnancy in which the viewer follows a pregnant woman as she roams the streets of Rue Mouffetard in Paris. Varda combines her alluring camerawork with the intimate understanding of her own ongoing experience. What is perhaps most invigorating about Varda’s work in this instance is its touchingly empathetic approach. Varda doesn’t allow the audience to become a spectator to the pregnant woman, but rather tries to align the viewer with her subjective perspective, impelling them to become enmeshed with her gaze and share the frustrations, impulses, and desires of the experience. The film plays out as less a story and more of an embodiment of a very specific and temporal viewpoint.

Here, she envisions an intimate and unique perspective, but in a film that is perhaps only achievable in the short format, due to the focused portrait and impressions it undertakes. As always, Varda, who was originally a photographer, transcends the novelty of the idea into a work of art through her elegant and seductive capturing of bodies, objects, personalities, and the world surrounding them. All of this is filmed within a monochrome pallet of fluid movement and enchanting compositions. Through the ongoing point-of-view camerawork, Varda aligns the viewer with her personal perspective and experience of pregnancy, and it is perhaps this unique level of personal attachment, which so frequently pervaded her films that have made Varda such a beloved director.

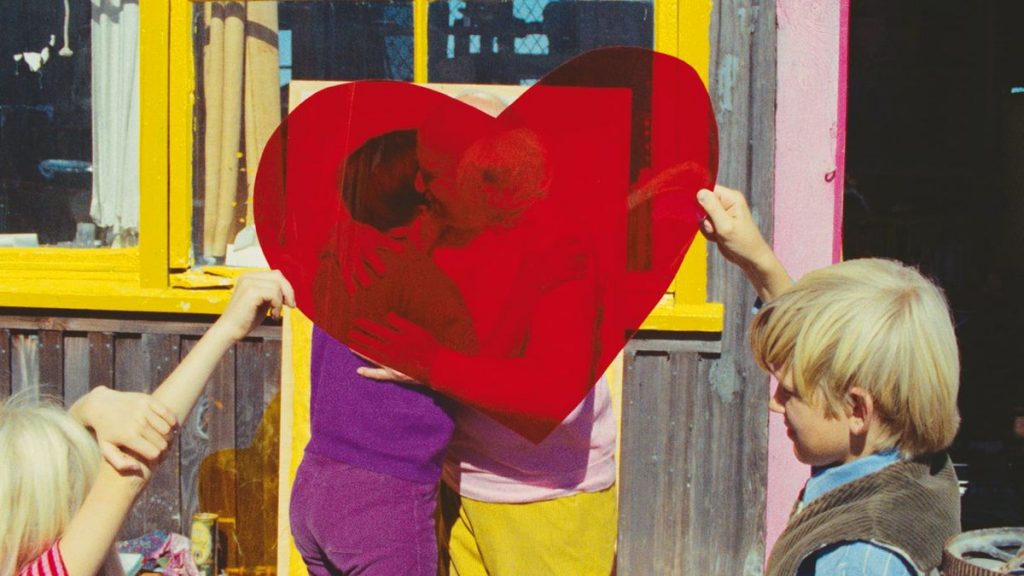

Agnes Varda infuses the piece with touches of sentimental beauty, quiet melancholy, and deft humor. As she allows her camera to focus on images of life, from children to the elderly, she symbolizes ideas of birth, growth, and eventually mortality – confronting the ongoing fears and hopes of the pregnant mind. The world, which is so often filled with expressions of dissatisfaction and indifference, becomes one of fear for Varda as she ponders the existence in which her child is entering. But, in equal measure and in response to this fear, images of children playing and laughing help to overcome the despondency of the lost citizens and provide symbols of hope in the surrounding bleakness.

Similar to Agnes Varda Movies – Official Poster For Cannes 2019 pays tribute to the French Legend

While on more humorous notes, she shares images of meat and men, reminding us of the carnal and emotive desires which pervade her character’s hormonally charged mind. Varda uses all of these idiosyncratic thoughts and observations to create a wonderfully rich and complex transference into the mind of the camera. The spectator now shares the vision of the lens and consequently, the ‘Diary’ becomes that of the viewers.

It’s a film without much linearity or direction, but it allows its audience to be transported through time, to see a different world, and through a different perspective. But perhaps more importantly, it invites the viewer into Varda’s own ongoing mind’s eye in the year of her pregnancy. It’s possible that in the history of cinema there has never been a director who has offered themselves so intimately to their audience, and here, in this most poetic of films, Varda presents herself in complete vulnerability during one of the most cherished moments of her life.

UNCLE YANCO (1967)

In Uncle Yanco (1967), Varda once again allowed her camera to become a mirror into the exploration of herself. While she invites the audience into the intimate journeying of her life, she does so with an enormous amount of charm, acuity, and humor. The film revolves around her meeting with an estranged uncle of which she never knew she had. The film questions ideas of family and exactly what that means, and as it may be expected, the great discovery of the meeting is that artistry runs deep through the veins of the Varda heritage.

Uncle Yanco is a tender family portrait, but also a comedy of sorts as Varda plays with not only the people involved and the images which position them, but also the ongoing theme of truth. There are often scenes that are purposefully shown to be reshot and by making her audience aware of this, she self-satirizes the intimacy that she herself evokes and that filmmakers so often profit from. Even in these moments of sincerity, Varda shows a distinct restlessness and a lack of satisfaction with simplicity, finding herself interrogating larger themes and motifs. Varda proves that she isn’t content with typicality; her films can never be ‘just’ stories, they must be visual works of art or philosophical essays, and it is the denseness of her work that continually elevates her as an artist.

Despite the larger themes at play, it still manages to be a deeply affectionate and fun film and one that allows Varda to find herself in concurrency with our own discovery of her. Yanco himself is a delightful character and Varda introduces us into his world on the water with respect, compassion, and reverence. But while it is undoubtedly interesting to see this reunited family and Varda’s self-discovery, as always in her career, it is more about how than what. How does she decide to display the story, rather than, what is the story? She was, after all, a visual artist far before she was a writer. During the film, Varda employs a playfulness reminiscent of some of the most enjoyable Nouvelle Vague films. With an upbeat soundtrack, playful editing, self-effacing humor, delightful colors, and the joyful Varda family at the center – Uncle Yanco plays out as perhaps Varda’s most warm film. The effects of the exuberant filmmaking bring memories of the exquisite comedy which Godard directed of Anna Karina. The tint of joy directed through Varda’s colorful eyes helps connote the sense of homeliness in which she finds in an unbeknownst unity of thought, humor, and being.

Related to Agnes Varda Movies –TIFF 2017: NEW IMAGES & CLIP FROM “FACES PLACES”

Beyond the film’s visceral pleasure, it would be a mistake to recognize the film’s moments of self-reflexivity and inquisition of truth as merely a gimmick to further indulge the jovial tone. It is imperative to recognize that Varda uses these concepts to challenge the form of filmmaking, the question of truth, and the perception of images. Her interrogation of the fabricated forms of documentaries manages to somehow humorously undermine the sincerity of the film and simultaneously remind us of its artistic value. Varda’s ability to adopt intimacy, inquisition, and experimentation all under the guise of an explicitly feel-good tone reflects the diversity of her talents as a filmmaker and perhaps alludes to the artistry necessary and often unrecognized in non-fiction filmmaking.

SALUT LES CUBAINS (1964)

If all of the aforementioned films show Varda’s versatility as a filmmaker and her ability to question and reshape typical presentations cinema, then Salut Les Cubains (1964) went a step beyond this – questioning whether motion pictures can even be – just pictures? When one thinks of Cuba, it is almost impossible to separate the connotations of colour and exuberance that have for so long been attached to the country’s self-image. So, when Varda went to Cuba and shot a documentary on the country and its culture and ended up directing a film consisting solely of hundreds of black and white still images, you would perhaps assume that this would be completely incompatible with the buoyant preconceptions of the country.

To capture a country as grand as Cuba, surely you need the levitating camera of Urusevsky or the warm colors and suave suits amidst crowded streets which were provided by Coppola. However, after watching Varda’s meager attempt, it seems difficult to leave without remembering a world filled with an immense amount of brightness, vivacity and flow – even if this is the total opposite of the literal images cast against the screen.

By using the multiplicity of still images with the flow of cha-cha-cha and bolero sounds to bridge the staticity, Varda creates a sense of discontinuity and continuity concurrently. The permeating music and narration offer a sense of the ongoing motion and the perpetual warmth and flavour of the country, but the disjointed still images work by cracking the film into moments like fragmented memories. Varda welcomes us into her own memory and in a retrospective viewing of the film, it only grows in its appeal as the images play out like the shattered pieces of a forgotten past and a hopeful utopia. It is within the warmth of the dancing locals, the smiling faces and the overlaying native sounds that bring the colour to the film and while the black and white images remind us that the film is stuck in history (both in that of Cuba’s and Varda’s), it doesn’t distract from the innate vibrancy of its culture.

Related to Agnes Varda – Feminism and it’s Eternal Affair with Film-making

The warmth afforded by Varda’s vision also presents her power as a political filmmaker. Her films have often relied on a certain tenacity and didacticism, and here, she brings the same political weight to her message but does so by using a different angle to her activism. The film is presented with an affiliated adoration as opposed to her perhaps more recognizable style which is imbued with indignant condemnation. The joy in which she brings to the screen reflects her admiration for Fidel Castro’s Cuba and the image of an elusive paradise. Similar to her documentary, Black Panthers (1968), Varda’s political alignment in unity with her filmmaking prowess works to embellish the world she is capturing and grab the attention and support of her viewers. Through the affinity of herself and the people she filmed; her political filmmaking was created with such empathy and strength that it is difficult not to feel supportive towards the movements she championed. While history has gone on to suggest that socialist Cuban life was perhaps not as wonderous as Varda’s incredibly joyous filmmaking suggested, nevertheless, the film remains a remnant of hope, and the pervading optimism itself embodies a certain sort of undying paradise.

In Varda’s exploration of form, she extends on the work of films such as La Jetee (1962) in questioning the value of still images in cinema but also reminds us of the importance of sound. It is invariably the ongoing soundtrack that beats with energy and her narration that is spoken with both wit and affection that allows the film to achieve its vivacious utopian vision, even in the voidance of color and motion. Perhaps the notions of montage and revolution have always gone hand in hand since the earliest days of cinema, but like the Russian directors who went before her, Varda reimagines new visual means in the creation of utopian dreams.

ULYSSEE (1982)

Despite the vast examples of cinematic mastery found not only in the previously mentioned films but also further in the depths of Varda’s career, it is in Ulyssee (1982) that Varda potentially achieved her greatest work under the short format. She seemingly used the film to focus on the ongoing question of criticism and art and of authorial intention and meaning. It’s as if her camera and poetic imagery became a vessel for Roland Barthe’s writing.

This film, like many great pieces of cinema, leads to a fundamental questioning of truth – a theme explored in the likes of Stories We Tell (2012), Symbiopsychotaxiplasm (1968), or Chronicle of a Summer (1961), and even as previously mentioned – playfully touched upon in Uncle Yanco. But, while this inquisition may not be the first attempt to analyze the idea of ‘truth’, her interrogation of various artistic mediums underneath differing perspectives of memory help to offer an intriguingly original lens on an ever-fascinating investigation. Varda questions the value of film and our evaluation of it. With the simple motif of a single photograph, she asks the people captured in the photo, herself, and us, the viewers, what does it mean, and does it even matter?

There is also a cheekiness to the film which further strengthens Varda’s place as a unique auteur. Despite her intellectual study of memory, time and value, she cannot help but intrude on the images with constant comedic expressions. No matter the denseness of the material, Varda seemed unable to let her camera direct with any feeling of self-importance, continually bringing laughter and smiles to the images and the audience who view them. The film is also used as a discovery of memory. Her hazy memory is contrasted against the non-existent memory of the young child and the absoluteness of the photo. The photo itself is then compared to an art piece the young boy who was photographed did in trying to recreate the photo. It then questions context and the history behind the image and the ongoing political and personal histories during the time when the photo was taken. Varda fills the film with various concepts, themes and questions, but ultimately when the credits roll, the meaning of the image is undecided and left for the viewer to decipher. Agnes Varda, as typical of her filmography, allows her audience to view her life as she reflects on her experiences, relationships and mind. Yet, while adding a sense of her interior personality and the quirkiness of her singular artistic vision, she fills the action with an enormous number of questions about cinema as a medium and leaves her audience with no particular answers. It’s a film with such depth and denseness that to truly understand the gravity and complexity of Varda’s questions in a single viewing would be seemingly unfeasible and would perhaps be perfectly suited to a double-billing with Raul Ruiz’s The Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting (1978).

This film, more than any other in her oeuvre, can be seen to be an essay on cinema and art – a provocative analysis of criticism and creation. When asked about the film, Varda explained that she was questioning her memory and time, explaining, “that is what the cinema is really about: a re-examination of time, movement and especially the image.” In Varda’s description, she summarises not only the purpose of this film but of her entire filmmaking career. The images which float across the screen become the intersection of both a personal and cinematic study. Whether it be experimenting with form, dictating ardent political messages or conveying personal stories, Varda’s films are all wrapped up in a simultaneous dialogue between the morphing medium and the transience of her own experience.

In this study of semiotics and the notion of memory, Agnes Varda once again reminds her audience, through the juxtaposition of color and black and white photography, between motion and stillness, young and old, memory and truth, painting and photography, sound and image – that the only truth we will ever achieve is our own. She perhaps undermines the notion of criticism itself and reminds her viewers of the importance of joy and pleasure – instructing us that the value of cinema and life itself, is and can only ever be, one’s own.

While these shorts all show experimentation with film, unfortunately, it would be a lie to claim that they seem to have left a large legacy on cinema. They haven’t perhaps changed the way cinema is created but they certainly leave questions on how cinema should be viewed and valued. Varda constantly asked questions of the medium and recognized the importance of always questioning how, through all of the various and wonderful facets afforded to directors, it is best to convey an emotion, a story, or an idea. She often confessed to entering into the film industry completely naively, stating that she’d only seen about ten films by the time she was 25. Yet, while this may seem sacrilegious to the most passionate of cinephiles, it is perhaps this exact naivety that let her become such a distinctive director. The medium of film was not met with a pre-established code or sets of conventions as it was for her contemporaries, filmmaking was an abstract space and a blank slate that she could transform and make her own and it’s for that reason that her films were always filled with a level of reinvention that continues to stand out in the annals of film history.

While her narrative films show an artist at her purest and most remarkably precise, her short films show roughness and playfulness, imperfect experimentation, and a remarkable mind that reminds viewers why cinema was ever able to transcend its role as entertainment and to be regarded as the seventh art. If the recognition of her feature films in recent years have shown us the necessity for female filmmakers, let her poetic short films remind us of the necessity for new innovators, directors, and critics to constantly revisit the fundamental question of ‘how’?

Agnes Varda Links – IMDb, Wikipedia