Lee Chang-dong rose to popularity among the mainstream audience after the release of his psychological thriller “Burning,” but he is not new to the festival circuit. He is a revered filmmaker in International film festivals known for exploring the social and political climate of South Korea in his films.

Lee Chang-dong has written and directed six films so far in his career, which spans over 20 years. His greatest achievement is that at least five different films could top the list, and their fans won’t mind that. Before discussing his films, it is essential to know about his life before his foray into cinema.

He graduated from Kyungpook National University in Korean literature. He was involved in directing and writing theatre plays during his college time. He is a celebrated literary figure in South Korea whose fiction earned him accolades. “There’s a Lot of Shit” won him The Korea Times Literary Prize in 1992.

In the Criterion edition of Secret Sunshine, Lee Chang-dong describes his creative process as one of utter despair. It is not surprising if you have seen his work. In his films, we see characters living in a solitary existence, consumed by repressed grief, against the backdrop of South Korea’s regressive socio-political environment.

In some of his grimmest movies of the past few decades, he’s tackled such themes as his country’s oppressive recent history (Peppermint Candy), the sexual victimization of women (Oasis and Poetry), questioning the religious belief and faith (Secret Sunshine), and the hopelessness that young people feel in an increasingly inscrutable world (Burning).

His films require multiple viewings to unpack the emotional and psychological layers in the drama influenced by the volatile Korean environment in which he sets them. His unwavering and solidly structured plotlines invite the viewer to observe the behavior of troubled characters and deliver unflinching exposés of pain, trauma, and rage.

It’s difficult to rank Lee Chang-dong’s films, and I would not mind if any of his top five films on this list top the rank as all of them are exceptionally great. I think only a few directors would have such filmography. Without any further delay, here is the list of every Lee Chang-dong film ranked.

6. Green Fish (1997)

Makdong is an aggressive young man with fatalistic behavior. Discharged from the military, He returns home with a dream to unite the family and run a small restaurant with them. The problem is that the native has undergone radical change since he left. The modernization of the Korean militia society is underway after the financial meltdown in the 1990s. The township has sprung up in the distance. Discotheques and bars are replacing small food joints.

Related to Lee Chang-Dong Films: 75 Best Movies of The 2010s Decade

Lee Chang-dong’s debut film, Green Fish, is a study of human frailty against the backdrop of economic disparity. With a flair for adding melodrama to the predictable plot, he creates uncertainty in the characters’ behavior. The film reflects how socio-economic changes shape society and the people inhabiting it.

Makdong, in search of a job, finds himself in the care of petty gangster Bae Tae-gon (Moon Seung-Keun). Naive and emotional, Makdong forms the illusion of having a family outside the family when the gang members treat him like his own. Lee Chang-dong is less interested in the gangster drama unfolding leisurely.

The moment you find yourself hooked on the Gangster drama, Lee Chang-dong diverts your attention to Makdong’s family. Though he understandably focuses on the human drama, the sudden diversion feels bumpy rather than a smooth transition in the screenplay. That is the only complaint I could find in Lee Chang-dong’s complete filmography.

5. Oasis (2002)

It is serendipity that two of my most loved, transgressive romantic films of the century were released in the same year, Punch Drunk Love (dir. Paul Thomas Anderson) and Oasis. The lead characters in their films are atypical men who do not succumb to their limitations to garner sympathy. Neither of the filmmakers ever tries to appease its audience by making the character likable or heroic. They never judge their character for what they are, and that is where lies the strength of the film.

“Oasis” opens with Hong Jong-du (Sol Kyung-gu) released from prison after serving three years for a hit-and-run case. His immediate family has moved to a new place without providing the forwarding address. They don’t want him. They don’t even care if he is dead or alive. His mother is indifferent to his presence.

Hong Jong-du is socially awkward. His gleaming eyes and perpetual smile could be deceiving. You feel for him, but you would probably run away if you saw him in person. He lacks social and familial skills. Even after a cold reception and explicitly telling him how life was good in his absence, he doesn’t budge and sticks with the family, as if he doesn’t understand his family doesn’t want him.

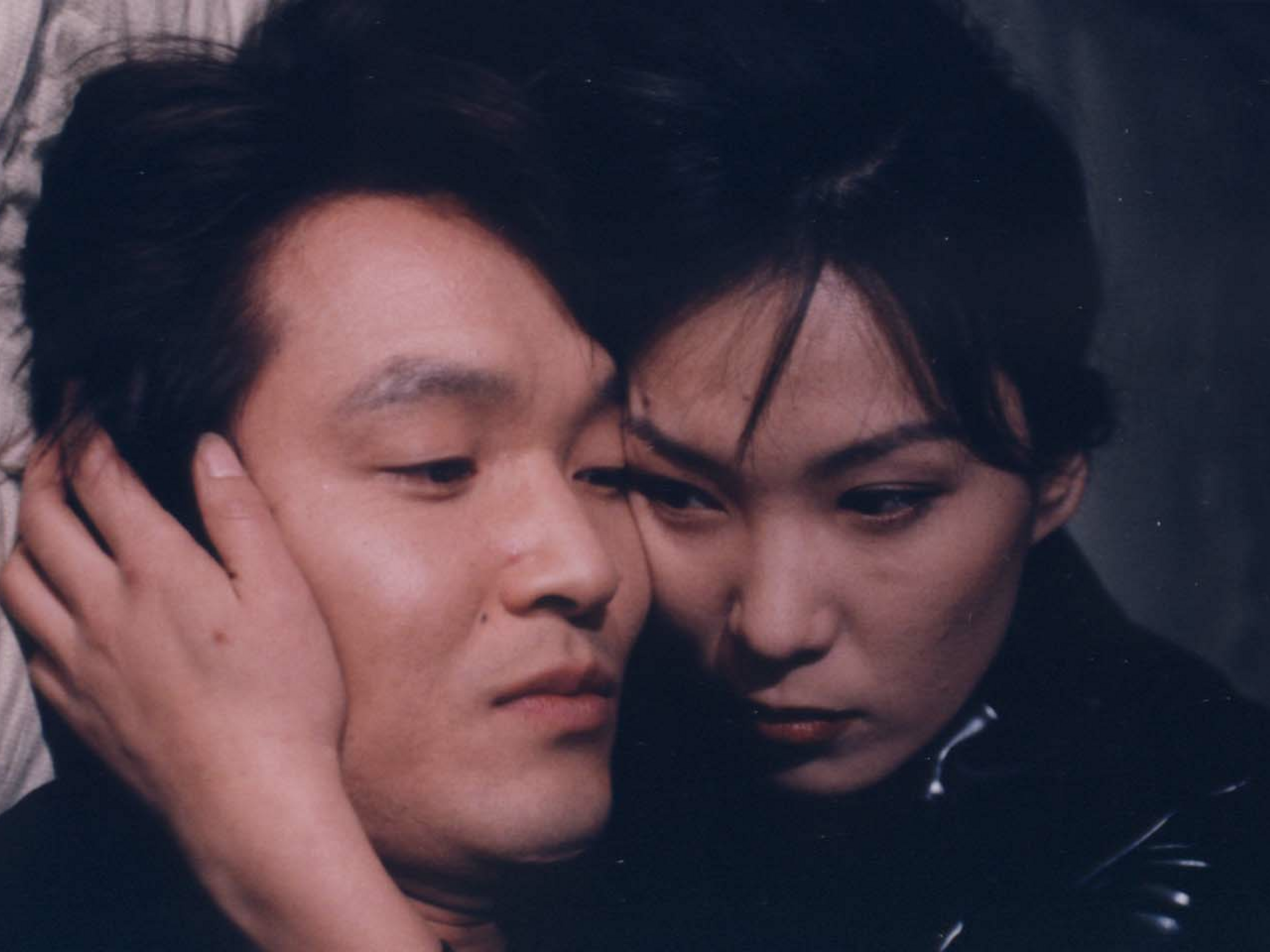

He meets disabled Gong-Ju Han (So-ri Moon), who is suffering from cerebral palsy, when he visits the family of the man he killed in an accident. Gong-Ju Han’s brother- and sister-in-law shift to a new apartment meant for a disabled person, locking her in a shabby small room.

Families abandon Gong-Ju Han and Jong-du. They are ignored and abused for self-gain. Lee Chang-dong doesn’t manufacture sympathy for them, and he doesn’t judge them. “Oasis” is a story of what constitutes love and desire between two physically disabled people in a perfectly abled society.

4. Burning (2018)

Every person has secrets buried deep down inside them, well guarded and protected, which in turn makes them mysterious. This mysterious aura, sometimes obvious, loud, and sometimes subtle, is fascinating and intriguing. It creates an independent and uncommunicative orbit that should be left untouched by others. Only explored at the discretion of that individual.

This elliptical orbit of mysterious aura and puzzling nature of an individual is patiently explored in Burning (Beoning), an adaptation of Haruki Murakami’s short story Barn Burning, except that it is set in Korea. Three distinctive characters intersect in this slow-burning psychological drama that examines the class conflict and tensive interpersonal dynamics emerging from brewing rage, sexual longing, and animosity, culminating in a queasy, bone-chilling climax.

The greatest achievement of Burning lies in the controlled and restrained narration that uses minimal exposition, relying on visual cues to express the airtight tension among the characters. The anger, grief, rage, love and envy are never explicitly expressed, rather it is internalized that is reflected in discomfort silences further heightened by Kim Da-won’s unsettling score.

Burning is a stunning, opaque story riddle with ambiguous enigmas and uncertain turns of events. It is rather a well-crafted and stunningly muted cinematographed film with absolute control over its writing, displayed in powerful characterization and a well-earned climax that you won’t see coming from five hundred miles.

3. Secret Sunshine (2006)

Lee Chang-dong’s films are about regular people doing regular things in their daily routines. No one is a hero or anti-hero per se. One of the residents describes “Miryang,” a small town where the film is based, as “just like every other place.”

Mastery of Lee lies in building a character out of those normal people out of their normal lives and weaving a simple narrative to reflect the socio-political and economic influence on these characters. With ‘Secret Sunshine’, Lee gets more intimate and personal to show a quest of a woman struggling to find the sunshine in the midst of personal loss, grief, and shaky faith.

Jeon Do-yeon’s committed performance and Lee Chang-dong’s dense writing render thematic complexity to the grief of a woman that requires multiple viewings. Lee spends two acts of the film, understandably so, depicting the grief of a woman who is going through hell, and he doesn’t cushion it or mellow it down for the viewers.

He keeps it as real and as raw that it will be excruciating to sit through some of the tormenting scenes. Jeon Do-yeon’s Best Actor (female) Cannes-winning performance is a testament to her incredible acting in the film that has to be seen to believe it.

Related to Lee Chang-dong Movies: The 40 Best South Korean Movies of the 21st Century

2. Peppermint Candy (2000)

Christopher Nolan’s psychological drama Memento wasn’t the only film in 2000 to employ reverse chronology. Far from the West, Korean screenwriter and director Lee Chang-dong, in his sophomore film Peppermint Candy, released the same year, also adopted the reverse chronology narrative. He examines a man unflinchingly and unhurriedly against the backdrop of the ever-changing and volatile sociopolitical environment in Korea.

Only in his second film, Lee Chang-dong displays the adroit ability in screenwriting that reflects the repressive social and political climate of South Korea and deft in his direction that only a few veteran filmmakers can boast.

The five phases in the protagonist’s life form the narrative in Peppermint Candy. It is structured in reverse order and opens with his suicide on the bridge, then goes back in time to his college days. It does a psychological exploration of Young Ho (Sol Kyung-gu) after he accidentally shoots an innocent girl during the Gwangju massacre in the 1980s. It leaves a scar on his psychology that turns into a blister under the military dictatorship in the Korean government during the 1980s to the economic crisis in the 1990s within the Korean government.

Peppermint Candy also explores the rise of masculinity in Korean society, which chews up Young Ho’s relationship with his wife and enables his toxic behaviour. Director Lee Chang-Dong explores one of the most tragic moments in Korean history in an extremely powerful way by portraying a male character who struggles within a militarized society.

1. Poetry (2010)

Contemplating the guilt and grief and articulating it to vent out during the existential crisis forms an underlying theme of Lee’s melancholic “Poetry.” Poetry is Lee’s most accessible work on its surface. Opens with a disquieting scene of teen-girl suicide and builds to the consequence it has on the people of that small town, including sixty-six-year-old Mija (Yun Jung-hee). That’s one way of looking at the Poetry. As we know, Poetry holds a labyrinth of emotions in its subtext. The emotional depth and psychological complexity Lee’s ‘Poetry’ carries is nothing less than a conundrum piece.

It would require multiple viewings to understand whether Mija’s life turns into poetry while she seeks inspiration to write one or she becomes part of a poem while figuring out how to write. Life plays a cruel joke on her that translates to poetry; she ultimately finds the inspiration to write one in the most unexpected of places.

Mija, a part-time caretaker living in a modest house with his grandson, learns about the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. There’s an irony to her tragic news when she joins the poetry-learning community. She has a wistful desire to learn a new medium of expressing herself while she is thrown into the abyss of unconscious forgetfulness of the language she knows well.