Paul Thomas Anderson is a filmmaker who refuses to indulge in escapism, instead holding a mirror to reality with an unflinching gaze. His films delve into the complexities of human nature—obsession, ambition, loneliness, and self-discovery—often with layered narratives that demand multiple viewings. Whether it’s the feverish rise and fall of a pornographic filmmaker in Boogie Nights, the intricate web of interconnected lives in Magnolia, or the simmering tension of unchecked ambition in There Will Be Blood, Anderson’s storytelling is rich with psychological depth.

His collaborations with actors like Daniel Day-Lewis, Philip Seymour Hoffman, and Joaquin Phoenix have resulted in some of the most compelling performances in modern cinema. Visually, his signature long takes, immersive tracking shots, and a distinct color palette create a hypnotic experience, while his partnership with composer Johnny Greenwood adds a haunting intensity to his films. Beyond features, he has worked on short films, music videos, and the documentary Junun. With nine masterful films to his name, here’s how they rank.

9. Hard Eight

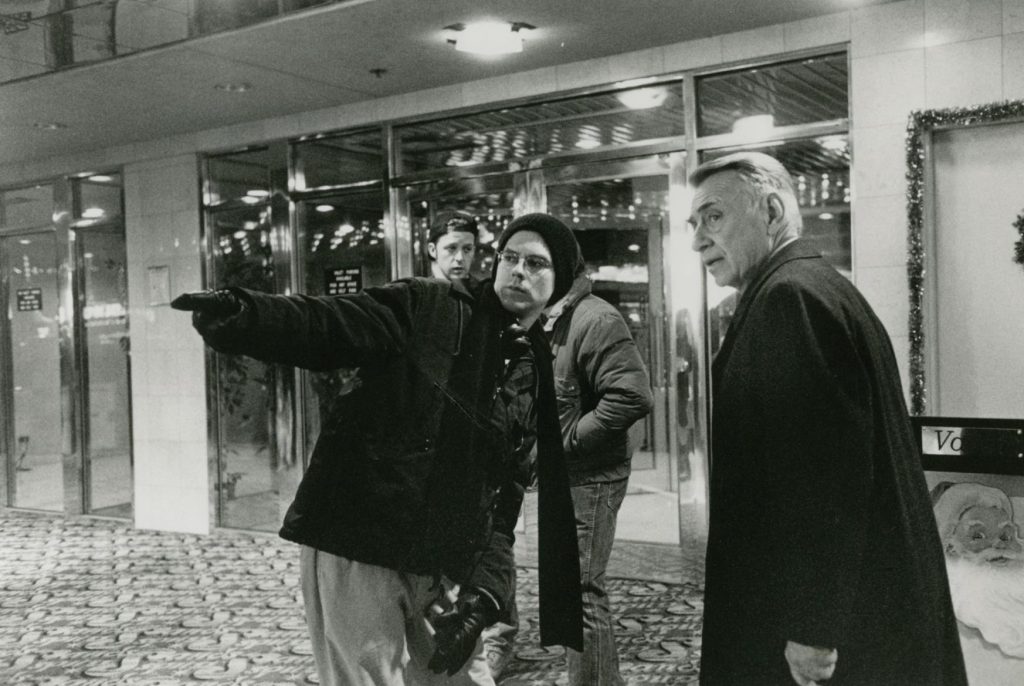

As Paul Thomas Anderson’s debut feature, Hard Eight demonstrated just how willing the writer-director was to swing for the fence right out of the gate. The film is an expansion of his own short film, the Sundance darling Cigarettes & Coffee (1993), and bears the distinction of introducing many of the thematic motifs he has since expanded upon on a decidedly grander scale, such as toxic masculinity, the search for one’s place in the world, and the notion of found family. Following an aging gambler named Sydney (Philip Baker Hall) as he shows a down-on-his-luck drifter (John C. Reilly) the ins-and-outs of his less than admirable profession, Hard Eight is as worthwhile a film to watch as any of Anderson’s other works if one hopes to understand his visual rhythm as well. One need only look to the film’s organic tracking shots to see how much of a master behind the camera Anderson already was by the ripe age of 25.

Hard Eight has more than earned its due as the film that allowed Anderson to go onto bigger and better things, but “better” is the key word there. In comparison to the more expansive and delicate films of the director’s filmography, there’s not much to dissect with Hard Eight either during the film or after it’s over. The chemistry between Hall and Reilly works well enough to create an engaging pseudo-relationship within the confines of the narrative, and Anderson must have thought so considering the two would go on to appear in his next two features. Plus, little did we know that a cameo from the late Philip Seymour Hoffman would give rise to an actor-director partnership for the ages. Nevertheless, even if Hard Eight’s low stakes and small-scale austerity don’t hinder it in any way, they also don’t give us much of a reason to return to it any time soon.

8. Boogie Nights (1997)

Anderson not only overcame the sophomore slump where it stood, but the sheer difference in quality and execution between his first and second features is more than staggering. Perhaps it’s because he has yet to face a true challenge to his capabilities as a filmmaker and storyteller that he is so revered by the film community today. Another film based on one of Anderson’s shorts, in this case The Dirk Diggler Story (1988), Boogie Nights expands Diggler’s story into a sprawling narrative that concerns his transformation from an unassuming busboy named Eddie Adams (Mark Wahlberg) into a bonafide adult film legend. Through the family he finds under the tutelage of director Jack Horner (Burt Reynolds), not only is the porn industry made to look as professional and respectable as it is enticing and welcoming, but it’s never been more apparent how much Anderson cares about the characters he creates.

Regardless of what they bring to the table or what sins they commit during the film’s years-long saga, everyone is treated with the kind of grace and humanity they deserve when their quest for the American Dream leads them down a road that few are daring enough to tread. Even as the film abruptly, but matter-of-factly, shifts from the bedazzled excess of the 1970s into the impatient demands of the 1980s, where Horner and his team find their credibility threatened by the convenience of home video and the emergence of recreational drugs, Boogie Nights doesn’t waver much. We’re not expected to sympathize with the characters as their lives begin to fall apart, but are rather granted the pleasure of doing so. What their struggles lack in development or complexity are made up for in Anderson’s fluidity in constructing an unforgiving world, as well as the ensemble’s ability to convey an equal sense of unpreparedness and helplessness. Wahlberg, Reynolds, and Julianne Moore have rarely been better than they are right here, and, unlike his previous feature, this is an Anderson feature that offers so much that it’s worth returning to every time. It should be no surprise at all that Boogie Nights was the film that shot Anderson into the stratosphere, a place that is seemingly unwilling to let go of him.

7. Punch-Drunk Love (2002)

When, shortly after the Cannes premiere of Magnolia, Paul Thomas Anderson floated that his next project would be an “Adam Sandler movie” it’s difficult to imagine many critics took it as anything other than a hipster joke. Even now, there appears to be a debate as to how much metatextual critique of the romantic comedy, or of Sandler’s comedic persona and career, there is in this fascinating mid-career anomaly. The fact is that Anderson likes romantic comedies (and Sandler) and wanted to apply his own talents to the genre, creating an off-kilter odyssey scattered with moments of truly irresistible loveliness.

Sandler’s unstable salesman Barry and Emily Watson’s blunt but kind-hearted Lena eschew the usual conventions of Hollywood “chemistry”, but nevertheless radiate intangible warmth and love as the clear connection between these two lost souls forges amongst PTA and Robert Elswit’s flourishes of light and colour. Barry’s run-in with dodgy phone-sex operators and his torturous sororal relation strike a more sinister tone – for much of the film’s runtime you’re uncertain whether to scream or swoon. All is buoyed by the frenetic energy of a Jon Brion score that mixes simple, relentless percussion with crescendos of strings and sprinkles of Harry Nilsson music originally written for Robert Altman’s infamous flop Popeye (1980), another oddball romantic flick that served as inspiration.

Boogie Nights and Magnolia throb with the confidence of a cinephile given the resources to carry out his vision on the broadest canvas possible. Punch-Drunk Love speaks of a different confidence, in which Anderson realises that with his accumulated talents and prestige he can do whatever the hell he wishes. Casting Adam Sandler for a movie at Cannes? Of course! Integrating a human interest piece in Time magazine about collecting flight coupons from pudding boxes? Why not! Though the mix of genre and director may seem incongruous, Punch-Drunk Love is arguably the keenest demonstration of Anderson’s vision – a vivid portrayal of idiosyncratic romance, a reminder that all people are worthy of love.

6. Phantom Thread (2017)

Whilst Punch-Drunk Love saw PTA take a surprisingly earnest touch to a supposedly lightweight genre, Phantom Thread is the same director taking a blackly comic approach to one of cinema’s most vaunted. The film’s polished marketing and cast of British stalwarts led many viewers to believe that this 2017 effort was going to be as self-serious as The Master, or There Will Be Blood. Instead, we get a costume drama (emphasis on costume) tinged with absurdity and kink. Ultimately its a love story as peculiar and compelling as his work with Sandler fifteen years previously, enhanced by a coat of experience, both personal and professional.

Making the connection between the romance of Phantom Thread and that of Anderson’s relationship with Maya Rudolph is not tenuous – the director has admitted the inspiration for the story came after the care offered to him by his common-law wife when he fell ill -, making the film uniquely intimate and personal beneath the gloss of Jonny Greenwood’s score and arguably the best cinematography seen to date in his filmography. That PTA was able to create such beautiful images after his split from regular DP Robert Elswit is a testament to the command of craft he carries at this stage of his career. The camerawork, made in collaboration with the lighting team among others, excels in both marvellous, wandering tracking shots and meticulous stationary compositions. It is, simply put, a luxurious two hours to sit through, transfixed in the beguiling setting of 1950s London.

Its unconventional romance also serves to skewer the traditional conventions of such relationships of the aged genius and their unassuming muse. By affording Alma (a magnificent Vicky Krieps) agency, and arguably control, the screenplay adds a new dimension to familiar tropes, imbuing the once-dry costume drama with vitality and entertainment. The film is littered with indications that we are in the presence of true cinematic greatness, America’s greatest working filmmaker going from strength to strength.

5. Licorice Pizza (2021)

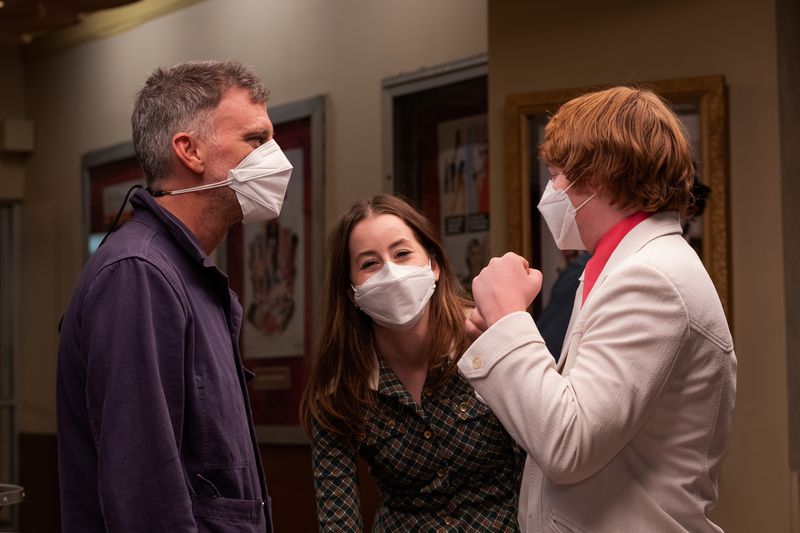

As much a spiritual successor as it is a historical predecessor to Boogie Nights, Licorice Pizza has already further solidified Anderson’s propensity for playing fast and loose with any notion of a plot, which, in his mind, is just a four-letter word. and constructing a world you can practically smell when the time and place are as distinct as they are here. Many true developments shape the backdrop of the San Fernando Valley of 1973, but all of them contribute to the free-wheeling nostalgia that Anderson creates through the kindred co-dependency Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman) and Alana Kane (Alana Haim) find in one another. Despite her best attempts to rebuff the advances of a guy ten years her junior, Alana cannot help but get caught up in Gary’s youthful idealism and join him in his various business schemes. Anything to distract her from the clear lack of discipline and direction she has discovered for herself in her early adult years. Their obvious age difference is made all but irrelevant as their mutual understanding of one another takes them for a ride amidst a swiftly changing landscape with an equal share of promises and hardships. The kind of landscape that perfectly emulates Alana’s repeated attempts to realize all that she can be now that she’s at liberty to do anything, but must do something.

For as skilled of an actor’s director as Anderson is, especially when it comes to allowing an eclectic ensemble to finely spread themselves across the canvas of a narrative, that he is willing to leave Licorice Pizza firmly in the hands of two actors making their film debuts is a testament to the patience one harnesses after a 25-year career. Hoffman crafts an image of a young man whose confident congeniality can only mask his ambivalence toward the real world for so long. That ambivalence is matched by the ineffaceable Haim, who brings everything from a blatant lack of interest in almost everything around her to a wide-eyed curiosity about the unlimited number of opportunities in front of her. It’s a practically violent internal struggle to reckon with Alana’s waning youth that she is able to convey so masterfully like many a lost soul protagonist of the New Hollywood movement, plucked from the hard-edged terrain of the early 1970s and released onto the equally unforgiving 21st century. Their pairing gives the film a tender, almost magical, sense of authenticism that makes it critical viewing for anyone hoping to engage with Anderson as he pursues the past in order to make sense of an uncertain, at times reckless, future.

4. The Master (2012)

Anderson’s sixth film has one of cinema’s most subtly provocative titles as it immediately beckons the question: who is the Master? Lancaster Dodd, the Hubbard-inflected quasi-religious leader whose brainchild, The Cause, gathers steam as they travel cross-country, seems the obvious candidate. He’s a master of the oratory for sure, as Philip Seymour Hoffman embeds the perfect level of demented charisma into his monologues, but it is suggested later on that his wife Peggy (Amy Adams) may be pulling the strings.

Whoever the ‘Master’ is, it sure isn’t Freddy Quell, the tortured war veteran played with harrowing physicality by Joaquin Phoenix. Disillusioned and tortured on his return from battle, he doesn’t seem to be in control of anything, trotting from place to place in a self-brewed drunken stupor before he comes into the magnetic field of the Dodds. Through memories, parties and intensive questionnaires Quell is put through a journey not dissimilar to those of a classic post-war American novel (Steinbeck in particular), but for him there seems to be no hocus-pocus cure for damaged goods.

The Master as a film is drama at its most gripping and psychological. Subtext and real-life allusions may take a back seat on first watch as the viewer is astounded by the technical proficiency of the piece, the careful creation of an eerie tone, at once a continuation and an evolution of the brand of formal brilliance seen first in There Will Be Blood. Films such as these truly set Anderson apart from his peers, whilst other pioneers of the 1990s indie boom have stayed in their wheelhouse, Anderson’s scope has expanded, and as he so openly channels Steinbeck and Huston its difficult not to acknowledge his newfound place within the pantheon of Great American Storytellers. It’s little wonder that of all PTA productions, this it the director’s favourite.

3. Inherent Vice (2014)

There’s a reason filmmakers have historically been apprehensive to adapt the work of Thomas Pynchon. Master of American postmodernism, the sprawling structure and scope of his novels lends itself almost exclusively to the freedom of the page. But Paul Thomas Anderson isn’t like most filmmakers, and in his euphoric, largely faithful, adaptation of Inherent Vice, he showcases talents in visual storytelling, comedic timing and delivery, and rich characterisations of figures who in the text occasionally slipped into caricature.

Whilst his preceding three pictures seemed to thrive on a subconscious tension created by visuals and score, Inherent Vice is going for something more lilting. Out goes classical music and in comes stoner guitar tracks and Neil Young ballads. Out goes Joaquin Phoenix as Freddie Quell, war veteran, in he comes as spacey private eye Doc Sportello. Despite this, there’s still lots be concerned about in the Los Angeles of 1970: crime, corruption and conspiracy at the highest levels of federal office, as well as the usual ragtag group of opportunist criminals and druggies. Typical of Pynchon, there is a *lot* of plot to handle in Inherent Vice, and its within Anderson’s understanding that the full breadth and scope of it will not be understood on a first viewing without a notepad and pen. In lieu of stationary the film can present itself as a delightful sensory experience, bathed in the sunlight of a bygone era. Anderson has long excelled in period pieces (he hasn’t set a film in the present day since 2002) but never has he recreated an atmosphere and aesthetic so lovingly, with fingerprints of Chinatown and The Long Goodbye visible on the celluloid, melding with the original author’s eye for eccentric detail within the largest of canvases.

Upon the movie’s release in 2014, for every critic swooning over the film there were three more bewildered and frustrated by its surplus of plot (yet lack of a story) and indulgent runtime. Rather than being inserted into the canon, like The Master or There Will Be Blood, Inherent Vice seems destined for cult classic status, the underrated gem in a filmography accepted with loving arms by fans eager to revisit its hysterical (in both senses) hysterical genius.

2. Magnolia (1999)

Clocking in at just over three hours long, Magnolia is Anderson’s longest film and also his most introspective. It’s a bit surprising to think that this was only his third feature, especially considering its assuredly grand scale and slice-of-life storyline that sees a multitude of complicated characters come in and out of each other’s lives in ways both big and small over the course of one rainy day in Los Angeles. Magnolia is a film that features so many Anderson trademarks, and one that so unabashedly wears its influence from the likes of Scorsese and Altman on its sleeves, that one may assume this was meant to be the grand finale Anderson would have saved for the end of his already storied career. On the contrary, it’s rather the film that legitimized Anderson as a force to be reckoned with when given free rein in the director’s chair. Featuring what is perhaps the director’s most star-studded and eclectic ensemble cast next to Boogie Nights, it’s the kind of film that represents what was once great about going to the movies and has since begun to fade; few filmmakers are still able to get studios off their backs and swing a major budget for a psychological drama, not to mention one in which action powerhouse Tom Cruise was cast as a seduction coach struggling to come to terms with the scarring emotional damage hidden beneath his misogynistic exterior.

Although Cruise gives what is arguably the best and most dramatically demanding performance of his career, his turn is just the tip of Magnolia’s iceberg, as the film is anchored by some of the rawest performances across Anderson’s entire catalog. The likes of Hoffman, Reilly, Moore, and Melora Walters, among several others, are all in service of Anderson’s symphonic exploration of generational trauma and how the fallibilities of parenthood manifest themselves over several decades. For such serious subject matter, however, Anderson is also sure to inject quite a few moments of off-kilter levity and charm to balance things out, which is more than enough to make Magnolia fly by despite its imposing runtime. Given the equal levels of confidence and indulgence that Anderson demonstrates throughout, there’s a lot of reason to believe that Magnolia is a film that should’ve died on the vine, but it absolutely works. Even if it feels like it never fully taps into the kind of greater meaning it purports to have, it’s hard to resist the chance encounters and twists of fate that provide these troubled individuals with the hope they need to endure the torrential downpour of everyday life, which sets the stage for an uplifting denouement.

1. There Will Be Blood (2007)

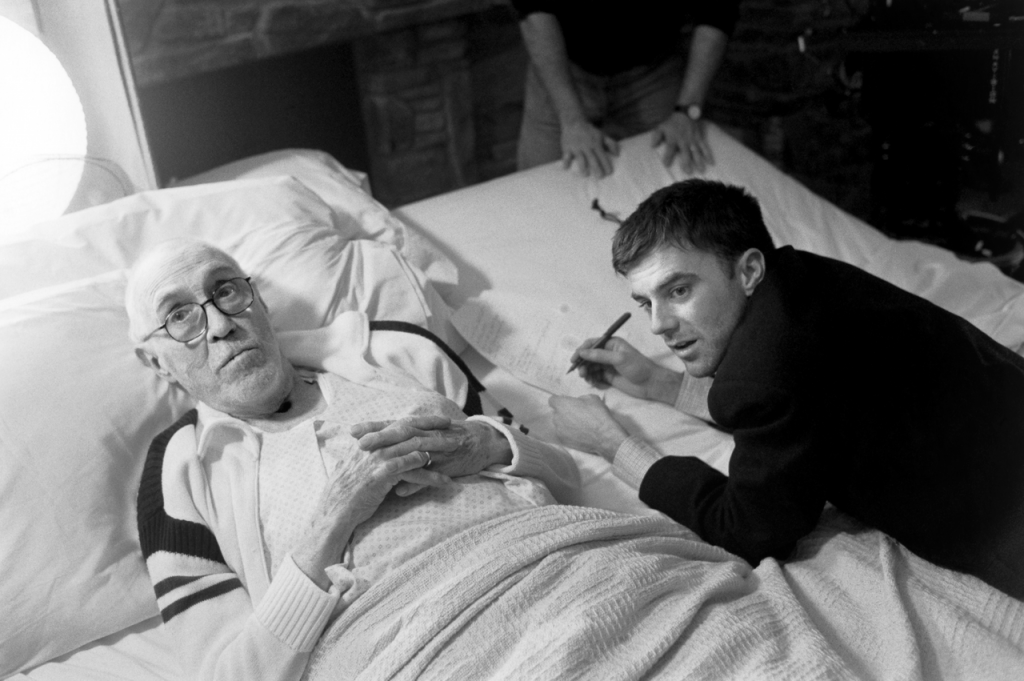

Well, you know what they say: “The bigger they come, the harder they fall.” It’s an adage as old as time, but one that’s perhaps most suitable to life in America, if nothing else. And given that Paul Thomas Anderson’s films tend to serve as microcosms of the American experience, it’s only fitting that his magnum opus take such a simple expression and unleash hell across three decades-worth of epic storytelling. Following oil prospector Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis) as he builds an empire in the early 20th century with his adopted son in tow while facing some fierce backlash from a young, equally conniving preacher (Paul Dano), There Will Be Blood sees Anderson trade in the San Fernando Valley of his youth for a decidedly different vision of California, though one with a similar form of tarnished promise across its vast desert landscape. Adapting Upton Sinclair’s exposé novel Oil! in the loosest sense imaginable, he forgoes much of the source’s social satire in favor of a more straightforward, at times blood-curdling character study of a modern-day Machiavelli, wringing out every bit of Day-Lewis’s expected charisma as he can to craft one of the most memorable films, and characters, of the 21st century.

It’s a testament to the amount of control that Anderson had over his own abilities at this point in his career that the legacy of There Will Be Blood has never been limited to Day-Lewis’s Oscar-winning performance and the seemingly endless discussions surrounding it. At the same time, the film is everything that Daniel Plainview comes to embody by the time of its startling resolution, in which his feud with Dano’s Eli Sunday comes to a head. With the moral crusades of these two self-made men, one a profiteer and the other a prophet, dominating the narrative at large, Anderson handily crafts a lamentation of an American dream that is never without consequence, one that is founded upon corrupt principles that ensure the success of few and the victory of none. In Anderson’s view, this is the same dream that many continue to chase almost a century after the matter. The fact that American culture has yet to fully comprehend the damaging effects of greed, excess, and ambition without a host of innocents paying the price first is but another reason to latch onto the ultimate American tragedy he created with There Will Be Blood. If Robert Elswit’s cinematography and Jonny Greenwood’s pulse-pounding musical score are any indication, as well, There Will Be Blood is a film that’s as fun to pull apart as it is engrossing to witness, and will undoubtedly go down as the crowning achievement of Anderson’s career.