Although the time-loop subgenre has historically been dominated by science fiction, crime, and horror, its most culturally durable reference point remains the classical rom-com strain inaugurated by “Groundhog Day.” That lineage was decisively revived—and popularised for a newer generation—by 2020’s “Palm Springs,” to the point where romance and repetition felt inseparable just at that moment.

The aftershocks travelled far enough for Bollywood to appropriate the device for a social-messaging exercise with “Bhool Chuk Maaf” last year. Yet the irony of the time-loop format lies in its own rigidity. Its appeal depends on novelty, but its architecture is aggressively constrained. Innovation becomes a survival tactic, not an embellishment. which is why the loop can never afford to remain in one tonal or generic register for too long.

This is precisely the space that “Berlin Loop,” the feature directorial debut of Emily Manthei, attempts to occupy. The film treats crime not as an end in itself but as a texture—something ambient, insinuating, and everyday. “Crime-tinged” is an accurate descriptor here, because the “Berlin Loop” is less interested in spectacle than in the quiet moral erosion that comes from proximity to illegality.

The narrative centres on Fatima, a disillusioned teenager working as a cleaning lady. Her face and physicality signal vitality and unspent promise, but her daily existence is shaped by the precarity of Berlin’s informal labour economy. She moves through the city guided by what looks like integrity, though one suspects it may simply be exhaustion masquerading as principle.

When instinct eventually nudges her into stealing a bicycle, the decision feels less like a rupture than an inevitability. In films that merely brush against crime rather than plunging into it, such acts often carry a specific emotional charge: sultry, impulsive, cheap with desperation. Here, that single theft pulls Fatima into the city’s shadowy bike-theft network, overseen by the casually menacing Windisch.

The theft day refuses to end. The loop resets, again and again, dragging Fatima through increasingly compromised moral terrain. But what’s interesting is how the film frames this repetition. The loop never feels fully involuntary. Fatima’s youth itself legitimises it. This is not fate punishing her so much as choice rehearsing itself, over and over, until its consequences become unavoidable. The loop exists less as a cosmic malfunction and more as a psychological condition.

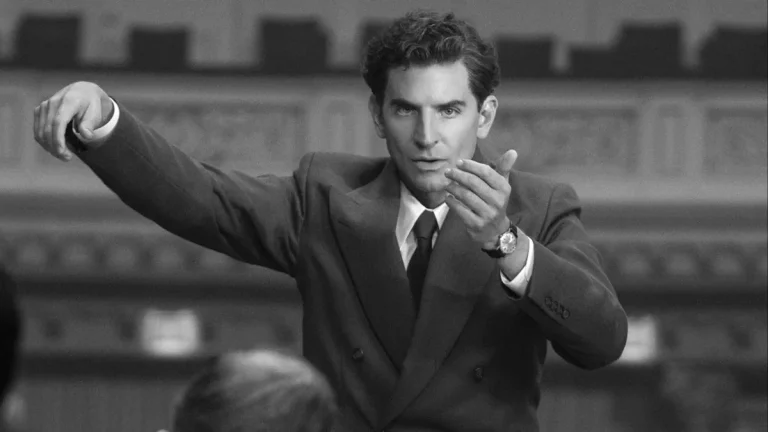

Where the “Berlin Loop” truly distinguishes itself is not in what it narrates, but in how it chooses to speak. Manthei’s writing smartly gravitates toward the rhythms of a coming-of-age comedy, allowing levity to coexist with unease. Windisch, played with elastic charm and latent threat by Thilo Herrmann, becomes the film’s most vital disruptive force. His garden-variety playfulness supplies the film with texture and ballast that would otherwise be difficult to sustain. This street-smart dangerousness never announces itself loudly, which is precisely why it works. His confrontations with Derya Akyol’s Fatima are marked by genuine tension—not the theatrical kind, but the uneasy friction of power imbalances that feel recognisably real.

Translating the monotony of low-level criminal labour into a literal time-loop, complete with a visible reset mechanic, becomes an inventive and frequently amusing gesture. For a low-stakes caper, the film benefits from its constant motion. Things are always happening, even when nothing is progressing. Within independent speculative fiction, this blend of genre-bending narrative design and socio-economic observation feels less like an experiment and more like a necessity—one that remains strangely underutilised.

The film grows more ambitious when it introduces classical strategic philosophy into this urban churn. The incorporation of The Art of War stands out as one of the film’s most striking conceptual moves. It promises a collision between ancient doctrine and contemporary survivalism. Yet this is also where the film begins to overreach. While the reference is intellectually stimulating, it lacks cumulative force. It gestures toward insight without fully earning it, resulting in a diffusion of momentum rather than its consolidation.

This dilution becomes most evident in the film’s relationship with its own title. “Berlin Loop” reads as a personal, inward-facing ode to the city, but it never develops a strong enough sense of Berlin’s personality to establish a grounded emotional connection. The city remains a functional backdrop rather than a living organism. This becomes a problem when the film’s central ambition is to critique urban class conflict. Such critique requires the city’s pulse—its textures, rhythms, and contradictions—to be felt viscerally. Here, that soul remains frustratingly out of reach.

Part of this can be attributed to the film’s guerrilla production ethos. Manthei has spoken about making the film without what she initially believed were essentials: a producer, a budget, and a commission. The achievement itself is admirable and speaks to a genuine love for the medium. But within this specific work, the reliance on a music-video aesthetic occasionally undercuts the film’s critical potential. There is also a pronounced insistence on narrative closure, on making everything add up neatly by the end. This urge toward coherence ends up muting the film’s sharper impulses toward cultural documentation and social critique.

At 87 minutes, and with supporting performances that struggle to match the lived-in intensity of the leads, “Berlin Loop” begins to feel slightly laboured in its final stretch. Still, its ambition never feels dishonest. The film’s synthesis of drive, curiosity, and formal risk makes Manthei a filmmaker worth watching closely. The loop, after all, is never involuntary when it comes to sharpening one’s craft.

![Lux Ӕterna [2019] Review: An Unwavering Scream at the Consumer Culture](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Lux-Ӕterna-Movie-Review-2-768x322.jpg)

![Implanted [2022] Review – A shallow A.I-gone-wrong thriller](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Implanted-Movie-Review-1-768x322.jpg)

![Complicity [2019]: ‘NYAFF’ Review- A Constant Struggle of Being an Outsider](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Complicity-highonfilms1.jpeg)