This final January 2026 update reflects late festival releases, reordered rankings, and a clearer critical picture of Indian cinema in 2025.

To write about the best Indian films of 2025 is less about surveying what is available and more about identifying what truly belongs to the year. And if one were to be honest, 2025 was not an exceptional year for mainstream Indian cinema. The machinery designed to churn out profit appears stuck in a peculiar limbo, where ambition has thinned out and risk feels almost allergic. Single-screen theatres remain largely extinct, and the re-release culture, once a harmless indulgence, now resembles a nervous tic, as if the industry itself is unsure of what new images it wishes to stand by.

Strangely, at a time when India appears to be racing ahead in adopting AI and machine-learning tools for cinematic production, the results have been creatively regressive rather than boundary-pushing. In an ecosystem already starved of opportunities for new talent, AI-rendered visuals and processes are being deployed in the most generic ways possible, flattening imagination instead of expanding it.

Add to this the increasingly visible hand of state-backed propaganda cinema, where certain films are actively suppressed to amplify others, and the larger picture feels bleak. Soulless star vehicles continue to arrive every Friday, while nepotistic gatekeeping has hardened into a system that transcends ideology. No recognisable face, no theatrical life.

And yet, within this stagnation lies something quietly consequential. 2025 marks a crucial political coming-of-age for Indian cinema. Mainstream filmmakers appear to have finally accepted a fundamental truth: no story exists outside politics. Attempts to bleach narratives of their ideological colour have begun to feel untenable, and in response, films are discovering sharper, more tactical languages of expression. That a producer like Karan Johar would back anti-caste works such as Homebound and Dhadak 2 is not a footnote, but a cultural shift worth registering. The politics are no longer whispered from the margins; they are shaping form, tone, and intent.

This list, then, gathers the films that resonated most powerfully this year. Many of them are not just films but flavours, gestures, and first steps. A large number are debuts, and crucially so, because firstness still carries a ferocity and rootedness that the industry otherwise risks losing. These works function as cultural milestones as much as creative ones. Of course, disagreements will follow. Translation falters, perception varies, and no list can be definitive. But the aim here is simple: to offer a set of assured recommendations from a year that demanded attention in quieter, braver ways. And as always, we welcome more.

25. Mrs. (Hindi)

Jeo Baby’s breakthrough Malayalam film “The Great Indian Kitchen” struck a nerve not just because it provoked conversation, but because it wedged the idea of a woman’s emancipation from the creaking jars and steel containers of her own kitchen, turning the perceived mundanity of domestic life into a quiet horror show. Arati Kadav’s “Mrs.”, a direct Hindi adaptation, softens the tone and leans into the everyday lightness of domesticity through the familiar grammar of Hindi cinema—but crucially, not in the way most Hindi films would.

Framed as a warm, lived-in portrait of a middle-class joint family, the film redirects its gaze towards the physical fatigue, mental abrasion, and quiet psychological toll experienced daily by its protagonist, Richa.

The triumph here is how Kadav carries forward the raw defiance of the original into a more mainstream register without defanging it in the slightest. Her storytelling is sparse, economical, and rooted. And Sanya Malhotra delivers a richly internal, moving performance—fully inhabiting a woman quietly clawing her way out from under the weight of expectations that should’ve long since crumbled into irrelevance.

Check Out: Interview with Sanya Malhotra

24. Tourist Family (Tamil)

Telling a story about good people and their good families, who spread warmth and positivity wherever they go, is tricky terrain. It so easily slips into syrupy territory, veering toward a sugar-coated sanitization of every human value imaginable. “Tourist Family,” Abishan Jeevinth’s directorial debut, treads that familiar line.

The moments of communal unity, love, and humour are straight out of the Indian family drama playbook. But context, especially in mainstream cinema, is everything—and here, it hits hard. This is a story of Sri Lankan Tamil refugees who row their way from Jaffna to Rameshwaram, and whose pursuit of a better life quickly becomes a struggle for survival until the world around them begins to soften.

What makes the film work is that it doesn’t build its power on the weight of its politics. Instead, it leans into melodrama, humour, and humanism to frame a portrait of India as it should be: a living mosaic of dialects, cultures, and messy harmonies, unshaken by strife and small-minded differences. In today’s climate, to even imagine that feels radical—and quietly powerful.

23. Lokah Chapter 1: Chandra (Malayalam)

With “Minnal Murali,” we got a charming home-grown superhero origin story, but “Lokah Chapter 1: Chandra” is the first time a Malayalam film has committed fully to the comic-book aesthetic. Writer-director Dominic Johnson leans into it with complete confidence, folding the pop-culture nostalgia of his youth into the older, darker nostalgia of Kerala’s wronged yakshi folklore. The result is a smart, funny, and surprisingly grounded story about Malayali youngsters trying to navigate the chaos of Bengaluru, a premise that sounds absurd until the film makes it feel oddly inevitable.

The weak link is the villain, who never escapes his stiff writing. As the climax approaches, he becomes haughty, tonally off, and unintentionally funny in ways that take the edge off the film’s larger stakes. Even then, the loverboy ease of Naslen and Kalyani Priyadarshan’s beautifully calibrated performance as Neeli carries the film with enough spark to sustain this franchise opener. The flaws are visible, but the ambition and personality on display make this a promising first fire-start of a series.

22. Superboys of Malegaon (Hindi)

The inspiring tale of macro-dreams nestled within the micro-aspirations of Malegaon’s scrappy filmmakers had already struck a delicate rhythm in the original documentary, where medium and message blurred with effortless grace. Over a decade later, Reema Kagti’s adaptation doesn’t try to reinvent that spirit—it reimagines it, giving those dreamers the full-bodied Bollywood treatment they always deserved. “Superboys of Malegaon” is light on its feet, achingly sincere, and soaked in a sepia-tinged warmth that’s impossible to resist.

Varun Grover’s screenplay feels especially personal. For a writer who’s long insisted that seeing yourself in a story is the most inexcusable principle of storytelling, this feels like his own journey folding into theirs—a quiet knot tying him to these passionate, makeshift moviemakers chasing light through the cracks.

From the goofy charm of its humour to the fragile bravado of its characters, everything lands with graceful precision. The world-building doesn’t feel constructed. There’s no flashy tug-of-war between craft and content; they melt into each other. Where the writing gently probes the inner lives of characters like Shafique and Nasir, the direction hums with the quiet, heartfelt energy of a filmmaker simply writing a love letter to the very idea of making movies.

More Related: Faiza Ahmad Khan & Nasir Shaikh’s Cinephile Legacy Finds Home In Bollywood & Beyond

21. Humans in the Loop (Hindi)

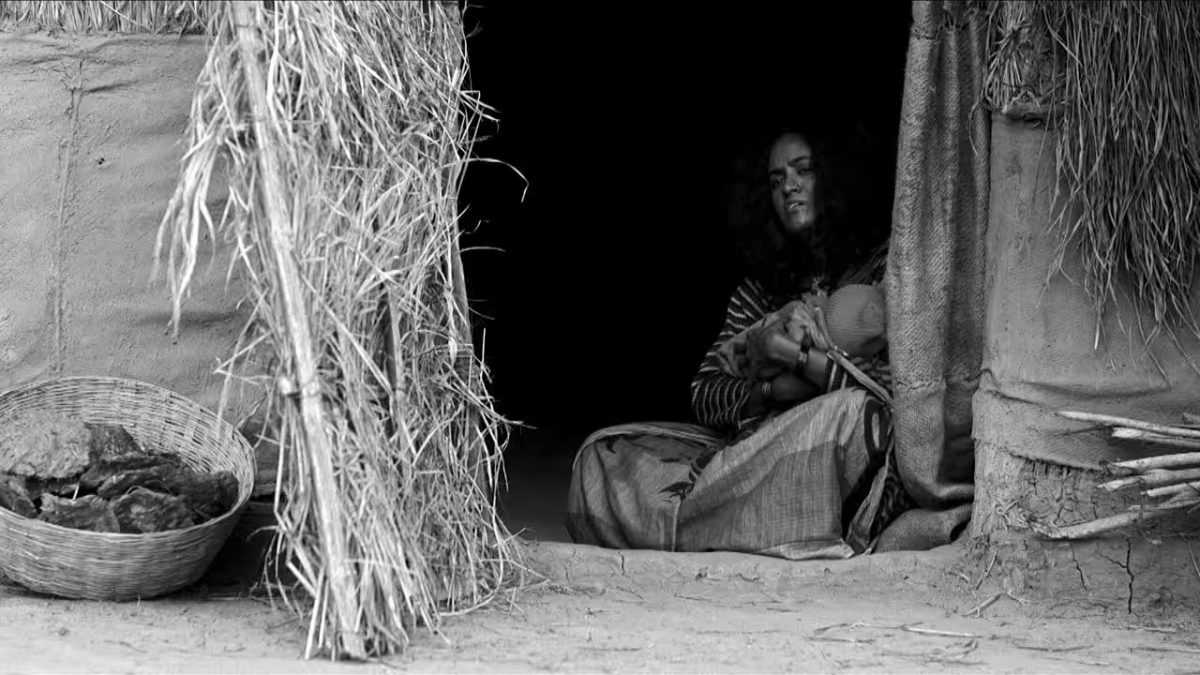

Shot over just twelve days near Ranchi’s Jonha Falls, Aranya Sahay’s “Humans in the Loop“ draws from investigative accounts of invisible labour in Jharkhand, particularly the countless women forced into cramped workspaces to serve the extractive, Western-driven demands of AI. Nehma, a young mother separated under the rigid dhuku system of the Sarna community, finds herself labelling graphics for offshore clients in a low-paid AI pipeline, even as she tries to hold together her fragile household.

The film quietly maps how her work mirrors her life: negotiating between the instinct to live fully within nature’s rhythm and the forced necessity to translate her lived reality into systems built far away from her world.

Sahay frames this not through grand speeches but through the tender, uneasy bond between Nehma and her daughter Dhaanu. Their relationship carries the weight of patriarchal inheritance, without pretending that awareness alone can erase it. The 1.55:1 storybook aspect ratio and compact runtime could have softened the film’s complexity.

Instead, they give its storytelling a clarity that never dilutes the social truth at its centre. What emerges is a culturally grounded, sharply observed film about a woman trying to make herself visible in structures designed to erase her. That it speaks in Kurukh, breathes in Sohrai art, and chooses simplicity without losing depth makes it even more quietly powerful.

20. Ponman (Malayalam)

More than a social or economic issue afflicting women, dowry—for men—often becomes an endless spiral, eating away at mental peace and livelihood. “Ponman” paints a stark, compelling portrait of this masculine conditionality. It’s charming, funny, and effortlessly gripping—a clever orchestration of clashing survival instincts. You root for one man as he squares off against his nemesis, a towering bully of a figure. But no one here is exactly wrong. The true villain is the broken backdrop: a fragile system that normalizes the demand for gold and leaves underprivileged families helpless in their inability to pay.

Based on GR Indugopan’s 2021 novel Naalanchu Cheruppakkaar, the film marks the directorial debut of acclaimed production designer Jyothish Shankar, and that background is evident in how vividly the spaces and settings are constructed. When Anurag Kashyap praised Basil Joseph as “one of the coolest everyman actors we have today,” he wasn’t exaggerating. As the titular “gold” man, Joseph dissolves into the narrative with a quiet, intuitive brilliance, sculpting the film’s heart without ever drawing attention to himself.

More Related to Best Indian Movies of 2025: Ponman (2025) Movie Review

19. Sister Midnight (Hindi)

On paper, Karan Kandhari’s debut feature looks exactly like the kind of India-set festival darling global juries love to applaud. Cannes recognition and Fantastic Fest acclaim only add to that perception. The film is steeped in concerns that deserve scrutiny, and some of its choices make that scrutiny inevitable. The dialogue often feels unnervingly foreign to its setting, the attempt to juggle black comedy with psychological disarray stretches the third act thin, and the cultural weight the film wants to carry sits awkwardly on its half-westernised shoulders. It is messy, uneven, and at times desperately trying to belong to spaces that do not claim it.

And yet, the reason it demands to be taken seriously lies in its striking aesthetic brilliance. The film’s stylistic imagination feels combustible and alive, like a chaotic street mural fusing classical Indian femininity with a raw, punk sensibility. The music holds the frames together, the visual language breathes with purpose, and somewhere between its tonal fractures and conceptual ambition, you begin to feel its strange pull.

Radhika Apte anchors it with one of her finest turns in years, playing Uma with a cold refusal to be softened, empathised with, or easily decoded. The film’s fractured sense of liberation comes layered, uneasy, and prickly, but it leaves you with something to wrestle with long after it ends, which is more than most films manage.

Related: Sister Midnight (2025) Movie Ending Explained & Themes Analyzed: What Baffles Uma in Mumbai?

18. Su from So (Kannada)

The most telling truth about storytelling lies in its simplest science: when we tell stories, we feel alive. When we hear them, the feeling doubles. That spontaneous exchange of energy, whether born of memory or invention, briefly convinces us that this act alone justifies existence. Comedy, then, becomes one of art’s greatest gifts. It exists to lift storytelling into an affirmation of life itself.

That desire for life to move freely, without moral policing or ornamental suffering, sits at the heart of JP Tuminad’s Kannada debut Su From So. On the surface, it resembles a familiar rural message film, where humour gradually gives way to correction and closure, complete with occasional traces of a tilak-wearing saviour figure.

However, reducing the film to that framework would overlook its true achievement. Su From So commits fully to an old-school, jokes-per-minute structure, a form many Indian films attempt but rarely land. The problem is not the archetypes themselves, but the absence of lived rhythm behind them. Tuminad understands this instinctively.

Playing Ashoka, a protagonist designed more as a conduit than a hero, he brings a restrained, almost diffident comic presence that quietly recharges every trope around him. The relentless background score and heightened drama are staged with visual care, but what truly sustains the film is its screenplay, which never loses sight of thought even while chasing laughter. In doing so, Su From So reminds us why comedy works best when it feels like a shared breath rather than a performed act.

17. Alappuzha Gymkhana (Malayalam)

The sports drama is a genre loaded with tropes, and most films lean on them for the sake of fidelity. It is a space where you can only break the clutter to a certain extent. Khalid Rahman, who last gave us the energetic and chaotic “Thallumaala,” has no hesitation in embracing the familiar arc of a boxing film. Yet “Alappuzha Gymkhana” refuses to let its genre define it. Instead of the standard rise-fall-rise trajectory, the film begins low and stays there. Even the brief high point in the middle arrives through nothing more calculated than chance.

What emerges is not a broad comedy, but one of the year’s most quietly affecting coming-of-age stories. Jojo’s eventual loss at the state-level championship becomes a window into a young man learning to move through life by following his own rhythm. The ease of finding your people and building a group where you belong without performance or pressure feels more urgent than any trophy. Rahman directs all of this with a laid-back confidence, and the cast, led by Naslen, carries the film into its stylish, almost dance-like stretches with effortless charm.

16. The Puppet’s Tale / Putulnacher Itikotha (Bengali)

When Manik Bandopadhyay wrote Putulnacher Itikatha in the early 20th century, he shaped it as a protest against the institutions and forces that reduce human lives to puppetry. Suman Mukhopadhyay’s adaptation honours that intent without bending the story into some modern, reformist overcorrection. The film builds its critique through a gentle, almost painterly portrait of Shashi, a young doctor returning from Calcutta to his village. His ambitions of going back to the city or even flying abroad barely animate him anymore, and the reason slowly emerges: a close, unrelenting intimacy with death that shadows his everyday work.

The writing moves with a softness that feels earned, never preachy. It unfolds like reading Shashi’s own diary, confronting his dilemmas with empathy and recognising that his conflicts come from an intellectual and philosophical space. Most films would stage the clash between modern science and local belief as an easy victory for the former.

Here, science only grows more fatigued and disillusioned. The natural light of the village seeps into Shashi’s certainties, unsettling them with quiet force. Filmed with remarkable technical control, the sound design and cinematography work in step with the performances to make every hesitation and fracture count. Abir Chatterjee and Jaya Ahsan bring a level of nuance that draws you in and holds you there.

15. Swaaha (Magahi)

It’s not every day you come across a film where the form and content feel knotted together, and with such stark sensitivity. “Swaaha” is a monochromatic social horror about a family of Musahars—a low-caste community historically classified as “rat-catchers” in Bihar—living on the fringes of an upper-caste village in Gaya, and the fatal night of their separation that pushed their anguish into a cry loud enough to echo through the town. It feels only right, then, that the film unfolds in Magahi, a language spoken by nearly 20 million people across India, but rarely heard or acknowledged in intellectual circles.

Though it deals with themes of marginalisation, witch-hunting, and the brutalities that follow, “Swaaha” isn’t built to raise issues. It’s an atmospheric, haunting work—an explosion of frustration from lives whose caste identity is inseparably tied to their economic displacement. One of its sharpest moves is how it watches religion with a careful, critical eye, tracking the split between mainstream deities placed on pedestals and the gram-devatas, local gods reduced to shadowy presences at the village’s edges.

The film holds itself together not with plot, but with an unrelenting visual atmosphere—and that’s where it lands hard. The writing may not always aim for subtlety, but then again, the film never pretends to whisper. Its independent folkloric approach isn’t looking for gentle affirmation. It asks to be stared back at.

14. Bison Kaalamaadan (Tamil)

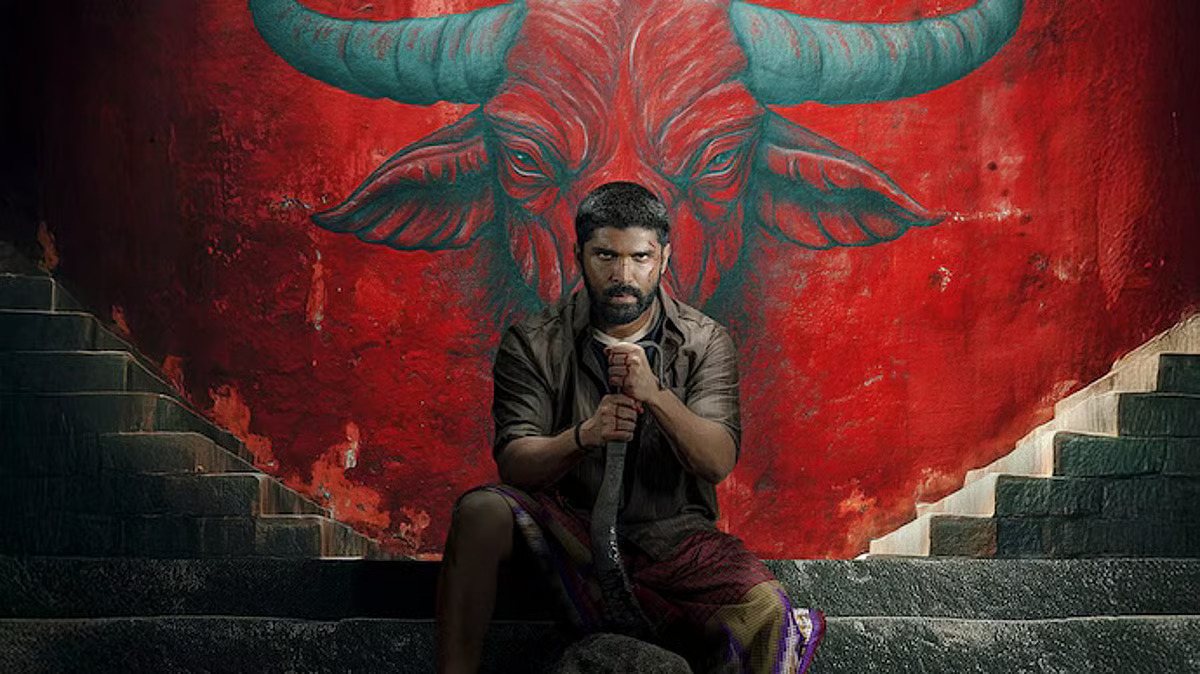

Mari Selvaraj remains one of the very few mainstream Indian filmmakers who understand that a person cannot be separated from the political realities that shape him. His cinema treats identity, caste, and circumstance as the spine of character, not as footnotes. In that sense, “Bison Kaalamaadaan” may appear like one of his more conventional choices.

A sports biography is the simplest label to place on it. Drawing loose inspiration from the life of coach and Arjuna Awardee Manathi Ganesan, the film builds a character study of a young villager whose devotion to kabaddi pushes him past the fences of political rivalry and caste inheritance he has carried since birth.

Selvaraj brings back the elements that by now feel distinctly his: potent animal metaphors, visual poetry that validates cultural memory, and an unbroken commitment to anti-caste storytelling. Yet the film never settles for the template that audiences might expect. The star presence of Dhruv Vikram, the gentle coming-of-age thread, and the defiant romance all fold into a story that gives its characters their full human weight. A father absorbs humiliation so his son can climb above it; a gang leader’s feud hides a deeper fight for dignity. Everything builds toward a film that turns accessibility into strength. The emotional sweep is large, but the honesty within it is larger still.

Related to Best Indian Movies of 2025: All Five Mari Selvaraj Films Ranked

13. Bad Girl (Tamil)

At first glance, Bad Girl seems like another entry in the coming-of-age lineage we’ve grown familiar with—one that might sit beside “Lady Bird” or last year’s “Girls Will Be Girls.” But Varsha Bharath’s debut quickly steps out of that frame. Light on its feet yet heavily stylized, the film leans into the confusion of growing up in a constant state of rebellion.

Through a firm, unembarrassed female gaze, Ramya emerges as a sharply observed protagonist—figuring out for herself why the “good girls don’t seek romance early” argument is flimsy, and why the lies told about her collide so naturally with the lies she constructs for her own survival. Toxic college heartbreak folds into an early midlife unraveling, and the film captures it all through a world that never feels sanitized or convenient.

What gives the film its genuine charge is Bharath’s instinct to tell a story that belongs unmistakably to her—relatable, familiar, but never reduced to cliché. These are words filmmakers often throw around, but here they feel earned. The truthfulness has no romantic padding, no softened corners, yet it lands with a sense of quiet magic.

Anjali Sivaraman’s extraordinary performance seals it as she turns Ramya into someone who isn’t just living a specific life, but someone who mirrors the confusions, impulses, and inherited patterns that follow most of us. The film’s emotional clarity comes from that very place—of watching yourself at an age where every choice feels both reckless and necessary.

Also Related: 10 Best Tamil Movies of 2025

12. Stolen (Hindi)

By the time we reach the final shot of Karan Tejpal’s thrilling, unexpectedly immersive debut, there’s a quiet sting in the face of Gautam Bansal—the bleeding ‘protagonist’—a hint of disappointment that his noble deed ended in futility. That very moment becomes the film’s key subversion: a jab at the urban saviour complex, undone not by failure, but by the absence of reward.

At its core, “Stolen” is a long chase—a survival thriller pitched between the state, two liberal urban elites plagued by guilt, and a volatile youth mob high on WhatsApp vigilantism. It tells the story of a tribal Bengali woman’s search for her kidnapped baby not by placing her at the center, but by folding her into the margins—mirroring her erasure—while the narrative barrels forward with the tension and propulsion of a road thriller. And crucially, instead of leaning on the novelty of its premise, “Stolen” commits to its politics. The film lays bare the ideological conflicts of its one-percenter perspective, refusing to let any of its characters off the hook.

With gripping performances by Abhishek Banerjee and Mia Maelzer, and lensed by first-time cinematographer Isshaan Ghosh with a fervour rarely seen in Indian thrillers, “Stolen” is far more layered than it initially lets on. It understands that, at its heart, this is a simple story about how kindness, when filtered through ego, class, and delusion, can boomerang. And it builds toward that truth with a stark, unflinching visual language that remains both sharp and gripping throughout.

Read: Stolen (2025) Movie Review

11. Dhadak 2 (Hindi)

When Shashank Khaitan’s “Dhadak” released in 2018, it left us split. It was a neatly staged romantic tragedy buoyed by two promising debutants, yet it committed an almost unforgivable sin by erasing the caste quotient of “Sairat,” the story it borrowed from so faithfully. Which is why the choice of Shazia Iqbal as the director of “Dhadak 2” feels like a genuine course correction. Iqbal, known for her blistering short “Bebaak,” steps into her first feature with a moral clarity and lived experience that immediately sharpens the film’s purpose.

Her adaptation of Mari Selvaraj’s “Pariyerum Perumal” works through the skeleton of the original, but refuses to be limited by the scale of a Dharma Productions film. Instead, she turns the mainstream canvas into a stage for analysing how caste violence and humiliation operate within supposedly progressive, academic spaces.

The love story remains, but it breathes inside an environment where inequality is not hinted at but examined with precision. Some of her narrative decisions land with a force that feels both unsettling and necessary. The pairing of Sidhant Chaturvedi and Tripti Dimri only amplifies the emotional and political charge of the film. The result is a commercial sequel starring two major young actors that also happens to be the most urgent and important Hindi film of the year.

Related Read: Caste was Never Part of My Story Until It Was: Featuring Dhadak 2

10. Ronth (Malayalam)

Few filmmakers in Kerala today hold as informed and self-questioning a mirror to the state’s policing system as Shahi Kabir. Having written “Joseph” and “Nayattu” and assisted on “Thondimuthalum Driksakshiyum,” Kabir has carried his conflicted familiarity with law enforcement into a filmography that keeps evolving in both honesty and craft.

With “Ronth,” his second feature, he brings that moral unease into full directorial control. Set over a single night where two nightwatchmen patrol the fault lines of their jurisdiction—and of their own wounded masculinities—the film unfolds like a slow descent into the silence between duty and decay. Its rhythm is unhurried but precise, its eye watchful without judgment.

Kabir’s command lies in how he keeps the horrors ordinary: suicides, elopements, abuse, and bureaucratic dead-ends pile up not as incidents but as symptoms of an institution rotting in plain sight. Roshan Mathew’s Dinanath and Dileesh Pothan’s Yohannan form a two-handed dance of fatigue and guilt, their shared exhaustion becoming the film’s emotional pulse. What begins as a procedural slips into something closer to poetry—a quiet elegy for a system too weary to collapse and too proud to heal. “Ronth” feels less like a story and more like a night that never ends.

9. Jugnuma (Hindi)

Sturdily comfortable at the junction of reality and magic realism, even if the narrative requires a fabulous cameo by Tillotama Shome to truly drive home the “fable” that acts as necessary context. What is interesting, however, is how the colonized and the colonizer within the film are clearly demarcated by the language spoken by the two sects, even if this could easily be misconstrued as a pretentious arthouse aesthetic.

What does work, within the context of both reality and metaphor, is the filmmaking itself, strongly cementing director Raam Reddy’s inspirations (take the final moment of Days of Heaven and use it as the incident for incitement and plot progression). The 16mm film camera aids immersion into a world where magic coexists with very real superstition, distrust, and corruption.

What also works—precisely because of its sparing nature—is the refusal to provide exposition, allowing ambiguity to persist within familiar frameworks of class divide, and of mythical and real lore intermixing with sociopolitical implications.

Deepak Dobriyal’s gravelly voiceover acts as connective tissue to the present, reminding us that the film itself is a fable, and that there is room for magic realism to comfortably cohabit—even in a country where myth and reality violently collide is hardly unfamiliar. Yet it is the film’s very real ecological messaging that permeates uneasily throughout, as does the suggestion that the liberation of the privileged may only be possible through the abolition of those very privileges.*

8. Mithya (Kannada)

There’s a strange sense of cultural inheritance when a deeply intelligent debut film reminds you of another. The rhythms of Udupi’s coastal life and the way Mithun, the protagonist of Sumanth Bhat’s “Mithya,” tries to belong there after arriving from Mumbai inevitably recall Chinu’s conflicted coming-of-age journey in Avinash Arun’s “Killa.” A decade later, this film carries forward a similar atmosphere, but filters it through a sharper, more bruised emotional register. Mithun’s attempt to exist between the warmth of his uncle and aunt’s household and the unprocessed grief of losing his parents is marked by a restless anguish and a confused longing for release.

Bhat’s patient, with his almost documentary-like gaze, treats Mithun with such tenderness that the film slowly places us inside his body, sharing his anxiety in unfamiliar spaces and silences. What unfolds is not merely a story about growing up amid loss, but a quiet recognition of ourselves, and how our emotional nature is often inherited from the cultures we grow within. The class divide between languages, along with repressed desire, lends the film a political undercurrent that never announces itself. Yet the mist-laden, gently poetic framing eventually gathers all of this into a space that feels unexpectedly warm, like a held breath finally letting go.

7. Eko (Malayalam)

Peeyoos, the protagonist of “Eko,” arrives with an easygoing, almost disarming charm. A young househelp with an open face and a relaxed gait, he soon reveals another register altogether: rugged, boyish, physically alert, and action-ready, yet curiously unsentimental and one-note. On the surface, these feel like traits of a very specific kind of man. Scratch that surface, and the comparison becomes clearer.

These are also the words we instinctively use for a dog. To carry that animal symbolism without reducing it to gimmickry demands an actor of rare control, and 28-year-old Sandeep Pradeep never loosens his grip in this bracing thriller, which pointedly refuses to follow any single character’s trail in a straight line.

Dinjith Ayyathan, who showed a keen command over emotional undercurrents in last year’s “Kishkindha Kaandam,” returns to familiar strengths here. His dog-populated universe remains firmly tethered to human behaviour, and narrative turns arrive as fragments of information rather than dramatic flourishes. With a larger canvas and greater resources, his control only sharpens.

The film is led with remarkable authority by Biana Momin, a middle-aged Meghalayan schoolteacher making her acting debut, whose performance quietly anchors the mystery around a near-mythic criminal figure. In that sense, “Eko” also reads as a sly provocation, nudging us to question our own appetite for legends and the stories we chase.

Also Check: 10 Best Malayalam Movies Of 2025

6. Homebound (Hindi)

At first look, Neeraj Ghaywan’s second feature seems far removed from the quiet tonality of “Masaan.” A decade later, he returns with a film that tackles its socio-political tensions with far more directness, setting a pandemic-era story against the wounded rage of India’s marginalised youth.

Mohammad Shoaib and Chandan Valmiki, two rural North Indian boys marked by different shades of otherness yet held together by friendship, find themselves chasing the one dream that remains both ironic and heartbreaking: a paying government job. It is the only form of respect that the nation still offers those it routinely pushes to the edges, which makes their struggle feel even more tightly wound.

Yet this overtly mainstream shell is exactly what allows Ghaywan to reach for something universal and gently human. “Homebound” never softens the reality of a young man forced to give up his education and ambitions to labour in a distant factory, thrown into an ordeal he never asked for. What it reveals instead is the tensile, often invisible hope that shapes our deepest emotions.

The sentimentality, the clear-hearted dialogue, and the openness of the film’s expression belong fully to Bollywood, especially with the Dharma logo announcing its entry. But because it is never arrogant about its choices, and because it treats its politics with humility and hunger rather than hostility, the film earns the weight of Scorsese’s name attached to it as executive producer.

Related Read: A Humanistic Mirror to India’s Fault Lines: Neeraj Ghaywan’s ‘Homebound’

5. Baksho Bondi (Shadowbox, Bengali)

What does it feel like to reconcile the persistent loneliness and sense of lacking in your life by clinging to the relationships you’ve chosen, however fragile or frayed they might be? Tanushree Das and indie cinematographer Saumyananda Sahi’s bruised, effortlessly moving directorial debut answers that question through a lucid, clear-eyed character study.

Maya is a woman who has, in some sense, chosen her poverty. She’s estranged from her own kin, in-laws are not even a memory, and she takes up odd jobs—tending chickens, working as a housemaid—to raise a son who’s already forced to act older than his years, while also caring for a husband, a former soldier, fractured by PTSD. It’s the kind of layered narrative that could have leaned on archetypes and still worked.

But Sahi’s writing instead roots the feminism of Maya’s solitary, hopeful existence in the contours of a specific, lived-in personality. In what might be the finest performance of her career, Tillotama Shome gives a turn that is heartbreaking and life-affirming in the very same breath. The way she draws out the resilience of Maya—never ornamental, never overstated—becomes a quiet lesson in how to exist in a world steered by the extremes of political and systemic indifference.

Check Out: Shadowbox (Baksho Bondi, 2025) Movie Review

4. The Great Shamsuddin Family (Hindi)

Only her second feature since “Peepli Live,” Anusha Rizvi’s “The Great Shamsuddin Family” unfolds as an almost real-time chamber piece. At heart, it is a high-energy family adventure, barely containing the pleasure of its own chaos. Set largely within the home of one daughter, the film thrives on the rhythms of an upper-middle-class Delhi Muslim household where every conversation spirals into banter, bickering, and affection.

Rizvi writes these exchanges with practiced ease, especially in how the women occupy the space with confidence and familiarity. Her direction stays measured, never showy, yet firm enough to let each performance rise. Dolly Ahluwalia, Farida Jalal, Sheeba Chadha, Juhi Babbar, Natasha Rastogi, Joyeeta Dutta, and a delightfully playful Shreya Dhanwantary anchor an ensemble that fills the frame with life simply by being present.

Beneath this well-earned warmth sits a quietly political and sharply observed character study. The home becomes an extension of Bani Ahmed, the film’s emotional centre and a clear personal stand-in for the director. What begins as an afternoon of routine frustration, marked by job applications and the desire to escape familial noise, slowly turns into a night where Bani slips into multiple identities at once.

She becomes sister, niece, daughter, and ex-wife, witnessing a distilled portrait of India as it exists today within her own courtyard. Kritika Kamra captures this shift with remarkable softness and control, grounding the film’s larger pleasures in an inward clarity that lingers well beyond its closing moments.

3. Ghaath (Marathi)

Chhatrapal Ninawe’s debut feature, nominated for the Panorama Audience Award at the Berlin International Film Festival in 2023, has finally found its global audience now. Told through the shards of a broken mirror, the film follows a handful of characters navigating Naxal-affected zones in Gadchiroli, Maharashtra.

This liminal space bordering Chhattisgarh becomes the cinematic terrain, where geography and ideology bleed into each other. With a fractured narrative structure, the often-invoked “Jal, Jungle, Zameen” is subtly repositioned: “Jal” becomes the in-between, the bridge linking jungle and land, while the looming presence of armed and ideological conflict binds the disparate threads together into something more cohesive than an anthology.

Despite operating in such a politically charged terrain, Ninawe’s lens remains deliberately neutral. The toxicity of those trying to assert their supremacy is unmistakably shown, and violence is often portrayed as cowardly. But even then, each character’s stance remains anchored in the ground they stand on—no belief feels alien to the world they inhabit.

And as for the cultural moorings of the tribals and Naxals? That’s where Ghaath quietly excels. It becomes a film shaped by its sound—the layered background score and sharply amplified dialogue crafting an immersive aesthetic, transforming what could have been a procedural into a haunting, deeply atmospheric political thriller.

Read More: Ghaath/Ambush (2023) ‘MAMI Film Festival’ Interview

2. Sabar Bonda (Marathi)

Winner of the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize (Dramatic) at Sundance this year, “Sabar Bonda” tells a story that, at least on the surface, feels like it aches all the way through: there’s forbidden sexuality, and so the kindling of a forbidden love; the setting is a small Maharashtrian village where social rigidity is treated like ritual; and the backdrop mourns the loss of a loving parent. But Rohan Kanawade—in his feature debut—approaches the personal-as-political with a tenderness that feels wholly his own.

Reframing the trope of the city slicker returning home, Kanawade examines the social architecture of love by placing it squarely within the boundaries of kinship and custom. In a humanistic stroke, the quiet romance between Anand and his childhood playmate Balya might not even register in the minds of their respective families, not out of regressive ignorance, but because the story is more interested in the grace of blissful unawareness.

The film’s strength lies in its ability to sit still within that emotional space. “Sabar Bonda” is as warm and sappy as the titular cactus pear fruits, but never fragile. It doesn’t shy away from the politics of identity and kinship, yet it does so without sneering at the hold that religion and family have over people’s lives. That quiet refusal to condescend makes this a rare and possibly first-of-its-kind film.

1. Second Chance (English)

Soft, slow, and light-footed films that follow the shifts of a mind rather than a fixed plot often find their way into our inner lives with surprising ease. Subhadra Mahajan’s debut, “Second Chance,” belongs to that rare set. It follows Nia as she returns to her family home in the Himachal foothills, trying to heal from the quiet wreckage of her trauma. The film never reaches for grand socio-political declarations, yet its tenderness lingers because of how precisely it locates healing in the fragile, imperfect bonds between people. Hours after it ends, the emotional residue stays with you.

Shot in black and white by Swapnil S. Sonawane with disarming honesty, the film steps away from the glossy romanticism of urban grief. It sees the world instead through the eyes of Bhemi, the middle-aged caretaker, her grandson Sunny, and the faith-filled simplicity of their small routines. Dheer Johnson’s debut as Nia is beautifully shaped, offering a quiet antidote to the usual coming-of-age drifter archetype. Kanav Thakur and Thakri Devi round out the film with performances so natural and quietly powerful that they end up grounding the entire narrative.