It is not possible to navigate the city of Paris without the eyes of Anna Karina looming up above you. She lies in Père Lachaise about half-an-hours’ walk east of Montmartre, but your eyes meet her’s far before you lay down flowers there — she is plastered on the billboards and in the Metro, smiling, locked into an expression of bemused nonchalance at the prospect of yet another re-release of the nouvelle vague features; maybe even in 4K this time.

It is always Anna Karina season in Paris, and it is always Godard season in Paris. And while Godard’s eyes do not shine out of every countertop photograph like Karina’s, it abruptly becomes clear entering the seedier parts of the city that the world that you observe with your own eyes — the Paris of gangsters and graffiti, of students and revolutionaries — is the world that Godard chose to set his cinema, and all cinema by extension, in.

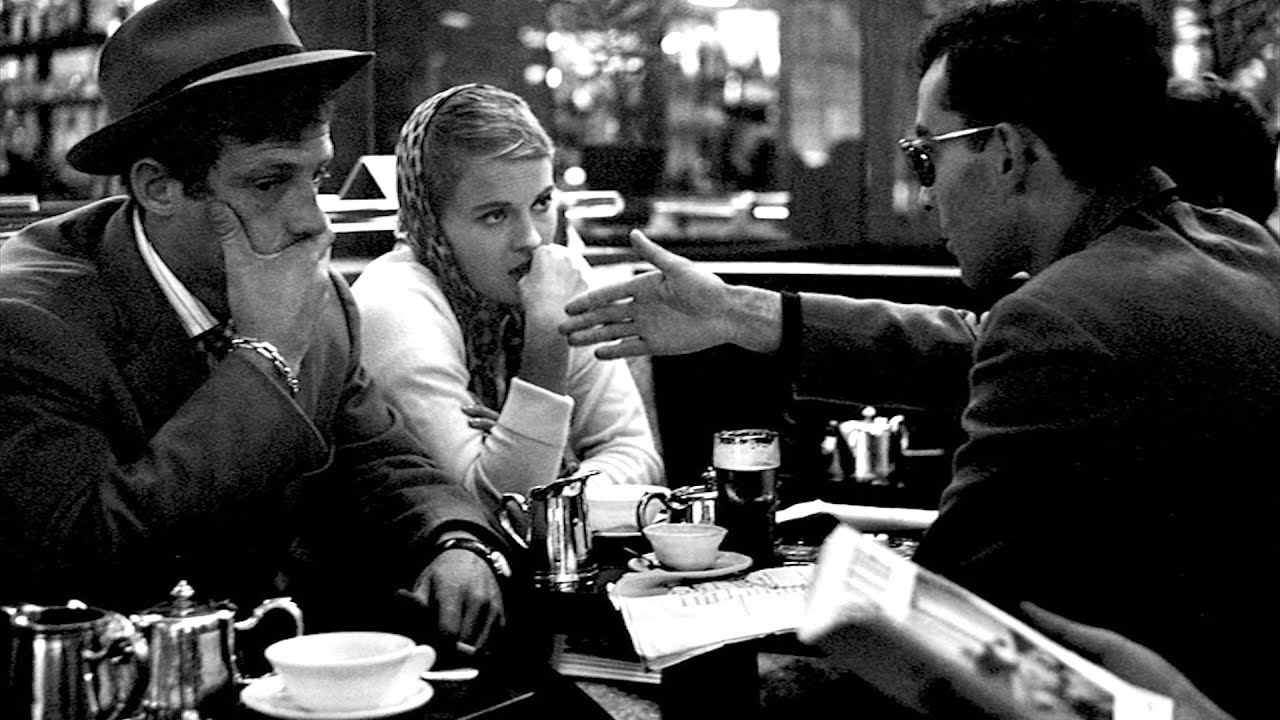

Godard would claim that his primary preoccupation was Marxism, but Godard is a notoriously poor authority on Godard, or really anything else (take his dismissal of Tarantino as a ‘knave’ indulging in postmodern pastiche, something that he himself created an entire career out of). While the politics of Godard’s cinema might have been overtly Marxist, his aesthetics remained primarily concerned with the enrichment of style. His personal style, first and foremost: never seen without sunglasses and a cigarette, in the company of one of his several muses. A master iconographer, for someone who claimed to be an iconoclast. It would form one of the many contradictions that led to the exaltation of his masterpiece “Breathless.”

Look: that there is cinema before “Breathless” and cinema after “Breathless” has been claimed ad infinitum. Ebert: “Modern movies began here.” On proceeding chronologically through any well-formed list of cinematic masterpieces, “Breathless” sticks out like a visceral gut-punch, carrying itself with a freewheeling intensity almost unmatched by any of its predecessors and aped relentlessly by nearly every one of its successors. Whatever cocktail separates the slam-dunk wheelhouse of modern cinema from the theater dramas of the Hays era seems to have been mixed right here.

It doesn’t seem to be about anything, for one — after screening a preliminary cut for Truffaut, who earmarked the parts of the film that could be trimmed out as per their unwillingness to move the plot forward, Godard responded by leaving in precisely the marked parts at the cost of any narrative development (or so the story goes). I don’t know if the result of this spirit of rebellion was accidental or a work of genius. But the film that came out was far more than an experimental retelling of a film ‘in the American style.’ It seemed to encapsulate everything that was good about cinema within it.

Godard and Truffaut were obsessed with the films of Howard Hawks, and nowhere were those films more compelling than in the apathetic self-assuredness of their chainsmoking protagonist, Humphrey Bogart. 1942 was a bad year for everyone, but not for Rick Blaine’s casual irreverence in the face of the war in “Casablanca.” Bogey stretched the conventional trappings of irreverence until it was sexy to not care.

His real-life girlfriend made it clear to everyone that to whistle, you simply had to “put your lips together, and blow”: only in Bogey’s world could it be so simple. And when he arrived on the screens of the French cinéma-clubs that Godard had frequented since he was sixteen, he imprinted himself so heavily and the psyche of the French that any work in the American style simply needed to bring him back in the form of Jean-Paul Belmondo’s Michel Poiccard.

Yet the Michel Poiccard of “Breathless” is a conflicting figure; as much as you are tempted to like him, he is relentless in proving himself to be nothing more than a poser and a womanizer (and, indeed — one’s personal enjoyment of the film may very well hinge on whether one finds Belmondo ‘cool’ or not). If he has any redeeming qualities, Godard is insistent on hiding them. Despite these efforts, however, he possesses a strange charisma that practically begs you to follow his misadventure.

What is going on here? How does this pathetic imitator of the greatest American actor of his generation have even a fraction of his appeal? Godard’s insight (and there were many he seemed to almost accidentally fall into — perhaps an inevitable consequence of trying to tear the medium down and build it back up from scratch) was that cinema being a visual medium, merely the aesthetics of Bogart were enough to hijack the viewer into viewing Belmondo as a glamorous figure. Godard’s tracking shots afforded him the center-of-the-world appeal that could only be given to a star of Bogart’s caliber, and the cigarettes and the hat did the rest.

Of course, Michel is cool. He must be — his visual conduct is inherently cinematic, and is it not the lens of cinema itself that endows ‘coolness’ upon men? Godard’s proclamation that cinema is a ‘girl and a gun’ is not merely pointing out that a love interest and a source of conflict are the only narrative tools you need to make a film. The fact that they are a girl and a gun is crucial.

The early-century development of cinema had established these two elements as the primary signifier of what cinematic meant. Godard realized that it worked the other way, too: by going the other way — by making a film about girls and guns — you could derive, independently, whatever made cinema tick. The code members that sought to regulate sex and violence in cinema were at odds not with sensibilities, but with the cinematic form. Sex and violence were not essential components of cinema — they were the underlying substance of cinema itself.

And that is what “Breathless” is, formally: a film pared to the essentials, everything taken out until there is nothing but sex and violence left. Much of the film takes place in Patricia’s (Michel’s mild American girlfriend) apartment, as the couple tumbles around angrily and indulges in fraught discussions. There is a detective plot in the background, which proceeds mainly through single shots and little dialogue. But the particulars of the police proceedings are not what the audience wants to see. Godard would rather watch people drive around in fancy cars and proclaim their love for each other; a man points out just what parts of a girl he likes while in a car.

Wouldn’t we all? Cinema is intrusive, voyeuristic, and infringes upon the world around it. Belmondo’s Michel was a film character, of course, but only insofar as he was on a screen. Bogart was an invention, Belmondo was a reflection. He was representative of the cinephiles of Paris, and of you, the viewer — the cinema fan who would light up a cigarette in the meager hopes of being perceived, perhaps from a side, as reminiscent of his heroes on screen. And now he was on screen as well. Is that why we lit our cities with neon lighting — because they looked good in the theater? Is that why we invented the DeLorean?

And so when you walk down the Champs-Élysées and face the impulse to hurl a pack of pamphlets into the sky and chant “New York Herald Tribune” it is not Jean Seberg you are summoning but Belmondo, with all his vagaries and his disgruntlement, and “Breathless” starts looking less like a celebration of cinema in all its glory and rather something more fatalistic. The grisly end of Belmondo’s character is your end, being preoccupied with a medium that is in so direct opposition to regular life, displaying by necessity only the highlights and the larger-than-life trappings of girls and guns.

Michel’s love of cinema is also his end. He is unable to live a life so much as play out a fantasy, where his American girlfriend can run off with him to Rome on a whisper, and where a few pseudonyms are enough to befuddle the police en route to capturing a murderer. Go home, says Godard. Life is not the cinema, and to believe so is a dire mistake. And the eyes of Anna Karina follow you all the way down the street as you walk back to your hotel in the rain.

![Fading Petals [2022] Review – A psychoanalytic albeit convoluted look at loneliness](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Fading-Petals-Official-Still-1-768x384.jpeg)