François Truffaut initially came into prominence as a critic for Cahiers du Cinema, where one of his articles, a scathing and derogatory critique of the stagnancy of the works of eight French directors of the day, became so widely discussed that he managed to find a regular spot at a larger magazine. With mentor and father figure Andre Bazin, Truffaut developed the auteur theory, which was poorly received until it found support from Andrew Sarris in the 1960s.

Truffaut’s voyage from a self-taught aficionado of literature and movies to one of the finest directors the world has ever seen may seem fairytale-ish, but the miracle did take place with the release of his first feature, the semi-autobiographical “The 400 Blows”. Before his premature death at the age of 52, Truffaut directed 25 films – five short of his personal goal of 30 – most of which are widely regarded by cinephiles across the world.

His films commonly feature characters trapped in claustrophobic surroundings, such as a stagnant or volatile relationship, leading to acts of rebellion and dreams of liberty. This list will feature a ranking of all 25 feature films of Truffaut. His three shorts, including the brilliant “Antoine and Colette” would not be ranked.

21. The Man Who Loved Women (1977)

The film begins with numerous women separately arriving to attend a funeral of a man named Bertrand Morane, whose life is then observed in flashback by Geneviève Bigey. The title derives from the name of the autobiography Bigèy had decided to author, which would have openly discussed his many relationships with women. Charles Denner plays the protagonist, with the rest of the cast consisting of the likes of Brigitte Fossey and Nelly Borgeaud. Truffaut wrote the script during the production of “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” (Steven Spielberg, 1977), where he acted in a crucial role.

Promiscuity is a recurring feature of Truffaut’s works, but in this case, the presentation of the obsessive-compulsive womanizer creates a sense of misogyny that gradually increases till the end of the runtime. Even without the misogynistic conundrum, the film is boring and superficial, incapable to hold the viewer’s attention following the initial period of curiosity. While Maurice Jaubert’s soundtrack and Néstor Almendros’ cinematography are excellent and the film features strong acting performances, the film remains one of the few misfires from Truffaut.

20. Shoot the Piano Player (1960)

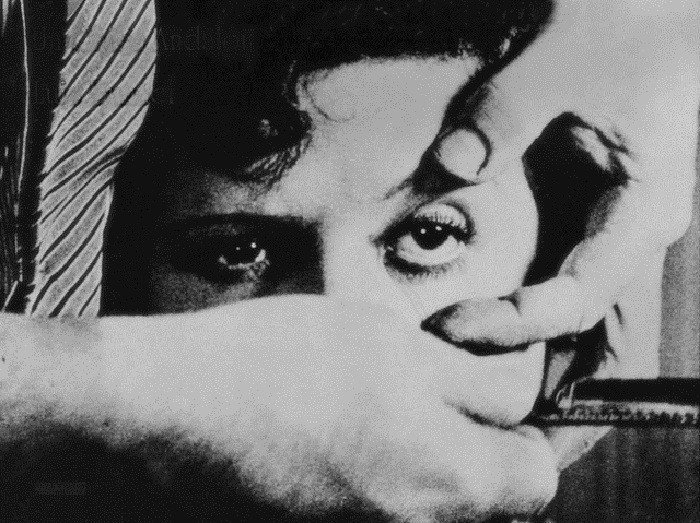

Here the list turns personal. Truffaut’s sophomore feature, a noir highlighting the aesthetic and experimental freedom of the French New Wave, is usually considered a major Truffaut work. However, the film banks too much on experimentation, often creating large chunks of monotony. The film, based on a novel by David Goodis, focuses on Charlie Koller, a bar pianist, who, alongside waitress Lena, gets involved in a troubling scenario including his brother and a duo of gangsters. Charlie Koller himself is hardly a straightforward person, as he isn’t who he claims to be.

Related to this François Truffaut film: Andhadhun (2018): An Ace Thriller from Sriram Raghavan’s Stable

Needless to note, there are some exceptional sequences in the film that feel like top-tier Truffaut, especially a scene where Lena surprises Charlie by holding his hand. However, it is unmoving and as inexpressive as Charles Aznavour’s so-so performance as the protagonist. As a thriller, it offers no excitement and little engagement. “Shoot the Piano Player” reminds me of “Diary of a Shinjuku Thief” (Oshima Nagisa, 1969), as both films bank on constant experimentation and are heavy on conservations about sex and personal or societal upheaval. Not unlike Oshima’s film, this too is unpredictable and soulless.

19. Fahrenheit 451 (1966)

Fahrenheit 451 is Truffaut’s only feature film made outside the Francophone world, and the resultant movie makes it clear why he remained rooted in France for the rest of his career as a director. The film is, of course, an adaptation of the watershed novel by Ray Bradbury. Truffaut’s adaptation is moderately loyal to the source material, although he makes two crucial changes, including one that even Bradbury seemed to like. However, Truffaut’s “Fahrenheit 451” is far from excellent.

Related to François Truffaut Film: Do Faithful Movie Adaptations Work?

Truffaut, a passionate bibliophile, realizes the emotional impact of helplessly watching books burn, and builds some effective scenes. The narrated opening credits add to the dystopic atmosphere. However, a major letdown is the horrible miscasting of Oskar Werner – whose relationship with the director severed during the film’s production – as Guy Montag. The director was used to working with small budgets and casts, and in this big-budget environment, his dystopia seems unstable and questionable. Bradbury’s original novel is an emotionally and morally scintillating read; this adaptation is merely a shell that offers nothing apart from periods of superficial engagement.

18. A Gorgeous Girl Like Me (1972)

Also known as “A Gorgeous Kid Like Me”, this minor Truffaut work is a study on a criminal woman appropriately named Camille Bliss, played by a brilliant and convincing Bernadette Lafont. Stanislas Previne, a sociologist, is striving to complete a thesis on criminal women, and the charming yet dangerous Camille is his subject of study. As Camille explains the story of her life, Stanislas finds himself falling for her charms.

Truffaut had explored the femme fatale narrative before and more successfully in “The Bride Wore Black”. Despite the prevalence of comic antics and a bewitching femme fatale character, this would have been barely watchable if not for the strong performance from the cast. In addition to the above-mentioned brilliance of Lefont, André Dussolier and Charles Denner deliver excellent performances. If the narrative had the opportunity to do the cast justice, “A Gorgeous Girl Like Me” would have been placed way higher on this list.

17. The Woman Next Door (1981)

Truffaut’s penultimate film, made in the same year as the incredible “The Last Metro”, is a perfectly acceptable watch, but pales in comparison when compared to the two movies it is sandwiched between. Like “The Man Who Loved Women”, this film is the visualization of description shared by a narration, in this case, Madame Jouve. The tale told is a tumultuous romance between neighbors and former lovers who rekindle their passion for each other and cheat on their respective spouses.

However, it is no “In The Mood for Love” in allure and discretion. The romance is both tempestuous and destructive, slashing through the hearts of Bernard and Mathilde and establishing personal and family problems. Truffaut usually strengthens this sort of narrative through masterful usage of shots and witty dialogues. Similar to those works, “The Woman Next Door” is stormy and intense, but unfortunately, it never inclines to reach excellence. Fanny Ardant and Gérard Depardieu fit their roles, although they are not at the top of their games.

16. Two English Girls (1971)

A scene from “Two English Girls” – an almost inverted version of “Jules and Jim” based on another novel by its creator Henri-Pierre Roché – still lingers in my mind. A very playful game involving Claude Roc, played by Truffaut’s muse Jean-Pierre Léaud, and his English acquaintances lead to a playful kiss through the bars of a chair. Set to a magical tune composed by frequent Truffaut collaborator Georges Delerue, the moment is strong enough to stop itself. However, the man and woman involved make the scene interesting from the narrative point of view.

It is Claude and Anne who kiss, not Muriel, who Anne wants Claude to woo, and whom Claude would soon come to love. The romantic and sexual tug-of-war between Claude and the two English sisters creates a highly promising concept. However, the film is overlong, remaining dull and stagnant for a substantial portion of its runtime. It is still a good film, but with a shorter runtime, it could – alongside its more loved thematic predecessor – have been one of Truffaut’s finest.

15. The Green Room (1978)

“The Green Room” marks François Truffaut’s final lead acting performance in films directed by him. Truffaut only took up lead acting opportunities in highly personal films, and here the personal ideas of nihilism and nostalgia lead to a commendable performance despite his typical lack of expression. The film tackles – almost like an Ôbayashi film – the chasms in one’s heart generated by the devastation of war. Truffaut’s character feels indebted to his dead friends and family and thus decides to pay his respect to them.

The film is adapted from three Henry James short stories, primarily “The Altar of the Dead”, and the restrained formalism of James perfectly gels with Truffaut’s ideas for the film. The film’s defeatist-optimist ideal can very well be a juncture of contention, but even the most critical viewer would feel the brilliance of the director’s amalgamation of the protagonist’s agony and the beauty of the scenic views shot by Néstor Almendros. Nathalie Baye’s Cecilia initially acts as a representative of the viewer, but then transforms into a more confused and concerned being.

14. The Soft Skin (1964)

“The Soft Skin” is most famous for being the originator of the famous cat scene in “Day for Night”. While the latter film doubtlessly recreated and used the scene extremely well, “The Soft Skin” needs more attention for its controversial, deep narrative. Truffaut explores a love triangle between publisher Pierre Lachenay, his wife Franca, and Nicole, an air hostess. Naturally, the plot is a hotbed for sentimental devastation, mental breakdowns, violence, and chaos.

Related to François Truffaut: 20 Best French Films of the 2010s Decade

Truffaut has always tried to emulate Hitchcock, and the mirroring is clear in the film. This leads to a major problem. Truffaut messes up in establishing his characters. While Jean Desailly’s Lachenay is intricately built, Francoise Dorleac’s Nicole needs improvement. Nelly Benedetti’s Franca is a mess, a mere repetition of the superficial cheated-upon wife mold. Nevertheless, the Hitchcockian style also lets Truffaut twist and turn his narrative, replacing the inertness of the plot in favor of excitement and mystery. Truffaut also has an iron hold over atmospherics, and the final product is as stylish as it is engaging.

13. The Bride Wore Black (1968)

For the majority of his career as a filmmaker, this enigmatic, thrilling femme fatale film, based on a novel by Cornell Woolrich, was Truffaut’s best attempt at creating a mysterious tale. Julie Kohler, played by Jeanne Moreau, attempts suicide but is stopped by her mother. She then leaves home and starts charming and killing off one man after another, only revealing her name to them the moment before their death. The reason behind the serial killing spree? That is the heart of the film revealed midway down the runtime and expanded upon till the end.

Jeanne Moreau is at her very best playing the emotionally vacant, captivating serial killer. Playing the “bride” driven by an irresistible intent of murderous vengeance, she captivates the men who once wronged her and her magnetism surely extends to the viewer. The screenplay is quite well-made, perfect for a film of this tone and substance, and it is visually miles ahead of Truffaut’s first color attempt (“Fahrenheit 451”) but it is Moreau’s characteristically striking performance that propels it.

12. Mississippi Mermaid (1969)

“Mississippi Mermaid” is often categorized as a minor Truffaut and remains one of the least-watched films from his oeuvre. Like “The Bride Wore Black”, this film is adapted from a Corne Woolrich novel, and here the entire cast performs to the top of their capabilities. The film tells the story of, well, another bride. Yet again there is a twist in the tale; the bride is a fake, a scammer eyeing the protagonist’s towering wealth. This original trick is the harbinger of misfortunes to come; the heart of the tale lies in the protagonists getting conned, either financially or emotionally. Louis, Julie, Marion, Berthe, and Comolli: all believe and lose.

Related to this François Truffaut Film: 10 Best Films of Roman Polański

Jean-Paul Belmondo (of “Breathless” fame) and Catherine Deneuve play the male and female leads, and their uneven relationship – although always passionate in love or hate – takes them from Reunion to multiple French towns in Truffaut’s most expansive film. It is also one of his most complicated tales, the extent of which becomes a detriment when the screenplay loses steam in the second half, but the chemistry between the leads and excellent cinematography showcasing both natural and urban beauty propels the film.

11. The Story of Adele H. (1975)

Victor Hugo is widely rated as one of the greatest masters of literature. The unfortunate tale of his erudite, promising daughter Adèle Hugo, whose erotomania led her to follow an English officer to the likes of Halifax and Barbados, is less known. Adèle maintained a habit of keeping a journal for the major part of her unfortunate journey halfway across the world. Truffaut’s film is primarily a loyal adaptation of this journal. The great author is never shown on screen as part of Truffaut’s contract with the Hugo family.

A 20-year-old Isabelle Adjani played the protagonist in her first acclaimed performance, winning awards left and right. The film is one of restraint, sentimentalism, passion, and a slow voyage towards utter destruction. Adjani fully comprehends the nature of the story – a study of the relationship and differences between body and soul – and becomes Adèle Hugo, leading to an authentic outcome. Adjani is not the finishing line of the movie’s positives. Truffaut’s direction is more stylized and patient than ever before. He tells the story with sorrow and marvel and creates a truly excellent work of art.

10. Love on the Run (1979)

The final installment of the Antoine Doinel Pentalogy is both its least and most interesting film. As usual, Antoine messes up the relationship with every woman he manages to impress in his life; this film shows four, including the return of a familiar figure from Antoine’s past screw-ups. Love, indifference, maturation, and hate become focal points of the movie, as Antoine, like real-life alter-egos Truffaut and (by this point) Léaud, searches for liberty and comfort.

Related to François Truffaut: 15 Best Films of Jean-Luc Godard

The fundamental complication in the film occurs in it banking almost too much on flashbacks. Antoine’s life flashes from his childhood to the present day, but this daily soap opera style, which feels like a nuisance, in the beginning, transforms into its trump card. “Love on the Run” is simultaneously a tribute to the greatest hits of Antoine Doinel and a brilliant non-linear tale of separation and reminiscence. Truffaut could have made brilliant soap operas if he wanted to, and here lies the proof. His narrative is so effective that it is easy to root for any character by the end of the film.

9. Bed and Board (1970)

“Bed and Board” sees our familiar Parisian everyman Antoine Doinel following his marriage with the reserved and brilliant Christine Darbon. Their domestic life seems cozy, but their youth – and the resultant immaturity and inexperience – quickly becomes a prominent hindrance. Léaud is brilliant as Doinel, and Claude Jade is typically excellent as Christine. The viewers have already grown to love the duo, having watched their bittersweet antics in “Stolen Kisses”, and here their relationship is more bittersweet than ever before.

Like “Love on the Run”, the fourth installment of the Antoine Doinel Pentalogy is not what it appears to be in the first few minutes. It begins as the sketch of an entire community and a slice-of-life masterclass. As the story progresses, other layers are discovered, most importantly claustrophobia and the lust for liberation. A light comic atmosphere persists throughout the film, and Truffaut masterfully stirs it with little occurrences and interesting, reassuring conversations, in turn creating a uniquely warm, forward-looking French experience.

8. The Wild Child (1970)

The technicalities of Itard’s methods of educating Victor can be and have very well been challenged, but Truffaut’s dramatization of the French real-life story – while going into excruciating details – is more about relationship and progress. While being forced to transform from an inferior being to a human, Victor falls into a striking identity crisis. This dilemma is never more apparent than at the conclusion of the film. Like “Stolen Kisses”, this too is a Truffaut creation radiating warmth, but in this case, the transformation from brutal, genuinely shocking violence to more delicate emotions enriched by Vivaldi is an advancement to behold.

Related to this François Truffaut Film: 10 Fascinating Child/Teen Prodigy Movies

Truffaut himself plays Itard, and his performance is driven by complex personal ideas, including the reflection of “I think that Itard is André Bazin and the child Truffaut” and “I was reliving somewhat the shooting of The 400 Blows, during which I initiated Jean-Pierre Léaud into cinema. I basically taught him what cinema was”. Jean-Pierre Cargol’s incredible performance as the wild child deserves acclaim; the director let him be unrestricted and communicated with him both in front and from the back of the camera, and he made the most out of it, delivering both thunder and flowers. For Truffaut, it is a typical tale of a rebel man, a social outcast.

7. Confidentially Yours (1983)

“Confidentially Yours” is Truffaut’s final film before his premature death. It is his first detective story since “Stolen Kisses”, with which it shares an iota of lightness. It involves a series of murders leaving real-estate agent Julien Vercel as the chief suspect. To save the boss who was so recently trying to fire her, amateur thespian and professional secretary Barbara Becker puts on the cap of a detective and tries her best to find clues proving Vercel’s innocence. Truffaut returns to the black-and-white world after a long time, and the result is a complete success.

The film is expertly fashioned, partly due to the extraordinary presence of Fanny Ardant as the amateur thespian and accidental (and equally amateur) investigator, and primarily due to the presence of the tangled, tightly knitted mystery that a detective plotline necessitates. To enhance the whodunit conundrum rich in secrets, surprises, and stalemates, Truffaut’s black-and-white world – streets and bars, police stations and cityscapes – proves instrumental, resulting in a stimulating, entertaining, and impactful finale from a genuine master of cinema.

6. Stolen Kisses (1968)

“Stolen Kisses”, the third installment of the pentalogy focussing on the ever-difficult life of Truffaut’s playful and ever-confused alter-ego Antoine Doinel, is a strange curio of a movie. It is the first that observes the relationship between Antoine and Christine, and it does so with childlike wonder. It seemingly is a detective story, but poor Antoine is so bad at being a detective that the film remains firmly determined in its existence as a perpetual comedy. Apart from Doinel and his acquaintances, another detective – a more pressing personality constantly following the most sympathetic figure in the entire film – is at play.

Related to François Truffaut: Best Coming of Age Films

Instead of being a mystery, a romance, or even a comedy, Stolen Kisses magically transforms into a comforting blanket of a film where the vanquished receive affection. This metamorphosis happens despite the narrative constantly developing one source of melancholy or another. Doinel is but a fool, and so is Christine, and while they pose as grown-ups, the real adults understand their naivete, and, instead of stifling their playful souls, facilitate their free spirit and encircle them in cordiality. Only Truffaut could have made a masterpiece out of an adventurous endeavor – unthinkable to categorize as part of a genre or describe without forfeiting its potency – so drastically different from the previous installments of the Doinel series.

5. The Last Metro (1981)

The Last Metro is yet another masterpiece from Truffaut and a practically perfect film. It takes place in Nazi-occupied Paris. Marion Steiner, wife of Jewish theatre director Lucas Steiner, must keep the theatre safe and running, all while hiding her husband from the Nazis and the ones supporting them. The arrival of Bernard Granger, an actor who secretly is a member of the resistance, creates the focal conflict of the narrative. The title refers to the fact that theatres were meant to complete their shows and allow the audience to catch the last metro, beyond which began curfew and chaos.

I was initially drawn to the movie because of its magnificent utilization of the various shades of red, but then the film proved to be a revelation beyond belief. Watching “The Last Metro” is like watching multiple films in one, yet none of the constituent narratives dominate the others. The collective performance of the cast – led by a brilliant Catherine Deneuve – is the strongest in Truffaut’s oeuvre. The Last Metro speaks of resistance: both passive and active. It speaks of joy, love, pain, dreams, heartbreak, and destiny. It never loses sight or waters down any of its important emotions and themes, preferring to keep a restrained dose of magic flowing throughout the runtime.

4. Jules and Jim (1962)

“Jules and Jim” is one of the most characteristic films of the French New Wave. The fairytale-ish tale of cheerful, extroverted Frenchman Jim, introverted Austrian Jules, and the enigmatic and lovely Catherine drew acclaim from all corners of the world, including from Jean Renoir (whom Truffaut both respected and criticized). All major traits of the movement Truffaut is most associated with can be found in the film: the desperate search for liberty, the emotional terror of love and relationships, and the strong feeling of carefree energy.

While Oskar Werner and Henri Sarre are brilliant, it is Jeanne Moreau who impressed me the most. Despite the ambivalence of her character, she is charming and mystifying. Georges Delerue is at his composing best, and Raoul Coutard manages to perfectly capture the constant rotation through zones of breezy and dark. Based on a novel by Henri-Pierre Roché, the film also serves as the home for multiple immortal scenes of world cinema: the tiny race where Catherine cheats to win is the most representative moment of the New Wave; the one where Catherine sings Le Tourbillon comes next.

3. Small Change (1976)

In “Small Change”, whose original French title translates to pocket money, Truffaut sends the viewer into the gentle and innocent world of children. The focus is on some students of a certain class in a particular school in a small French town, and their teachers and family. While the children create general chaos through their antics, Truffaut establishes a more serious tone through the poverty and haplessness of Julien Leclou.

I am surprised and disappointed at the unfair comparisons between “Small Change” and the films of Wes Anderson. With no disrespect to Anderson, whose works I adore, especially “Moonrise Kingdom”, which seems to have been influenced by this film, Truffaut does not bank on perfect symmetry, carpeting, and other enhancements to create an aesthetically stimulating atmosphere. Additionally, his wonderland in Small Change feels genuine, because it is. Truffaut has always been better at developing warm tales than scheming the coldness of noirs, and here he is at his warmest, masterfully deciphering the realm of children through numerous sketches accumulating to form an extensive study of an entire community. The final sequence left me stunned and breathless.

2. The 400 Blows (1959)

Truffaut’s debut film demonstrates how difficult growing up can be for a child who is pushed to dwell in uncaring environments. Every component of filmmaking comes together in “The 400 Blows” to deliver a landmark film. How else can I convey the beauty and emotional potency of a film clearly influenced by Truffaut’s life and showcasing a young Jean-Pierre Leaud’s acting genius? By using umpteen adjectives, perhaps, but I would possibly run out of them before being satisfied with my description.

Related to François Truffaut: The 400 Blows (1959): An Unsentimental Film about Adolescence

The film, which is both agonizing and breathtaking, focuses as much on the setting as it does on the protagonist, producing lasting moments in the process. Antoine Doinel is Truffaut. François Truffaut is Antoine who creates mayhem and breaks rules. He is, however, too immature to grasp that typewriters have serial numbers and is too young to understand his place in the world. “The 400 Blows” is one of the most famous films in world cinema and deservedly so. It immediately projects Truffaut as a great director, brings life into the French New Wave and kickstarts the storied career of Jean-Pierre Léaud.

1. Day for Night (1973)

Alphonse goes around asking everyone if women are magic, receiving myriad answers. He does not ask whether films are magical because he – a passionate cinephile – knows there is no confusion; he would receive the same affirmative answer from everyone he questions. Deriving its title from a cinematic technique known in France as the American night, Truffaut’s “Day for Night” is nearly two hours of passionate cinephilia that captures the magic of creating a film in the most perfect way possible.

It is sentimental, personal, full of characters positive and negative, surprises, and ideologies, yet never do we feel Truffaut overusing these elements to the detriment of the movie’s total impact. Truffaut does not solely focus on the lead actor or the director. Difficulties for the make-up artist, the script girl, and the propman are also important for him. Despite the questionable glorification of the director which enraged Godard, and after an exchange of letters, ended their friendship, this is Truffaut’s greatest achievement as a director and one of his best roles as an actor.