Since 2017, David Lowery has begun to emerge as an important auteur whose films are abundant in both staggering imagery and philosophical ideas. His recent creations, A Ghost Story (2017) and The Green Knight (2021) are, I believe, two of the most meaningful films of the last decades: they not only ascend to the visual heights of some of Terrence Malick’s and Andrei Tarkovsky’s best moments but also succeed in leaving the viewer in a state of intense contemplation.

The richness of symbolism and philosophical transmission, however, cannot be fathomed too easily. Judging from interviews in which Lowery tries to explain why he does what he does, it is perhaps because he makes his filmic choices quite intuitively. This makes the two films profound enigmas – for many viewers, frustrating enigmas – that scream for decoding and interpretation. One way to shed light on these creations is to look for common themes that seem to occupy Lowery’s mind as a mature screenwriter and director. Identifying these common themes can make the films not only more accessible but also beneficial for our own self-reflection.

Related to David Lowery: Andrei Tarkovsky as an Existential Cinematic Philosopher

Since neither A Ghost Story nor The Green Knight can be fully grasped after one viewing, feel free to read these lines before or after watching one or both of the films. Spoiler alerts may be irrelevant when it comes to films that demand a continuous deciphering and whose beginning and end are deeply intermixed, like the magical serpent ouroboros that keeps eating its own tail, continually being reborn from itself.

Dead Men Walking

What A Ghost Story and The Green Knight have in common is the theme of learning to face our own ending. Can we agree to die when it’s time? Can we accept the reality of our temporality and truly let go of our own cherished existence? If we do that, these two films tell us, this will lead us to maturity and liberation.

In both films we encounter two dead men walking. Even though The Green Knight’s Sir Gawain is physically alive, he is, much like the deceased C. in A Ghost Story, compelled to come to terms with his own cessation, since he keeps marching toward inevitable death. To be sure, both protagonists do their best to evade this inescapable fate and constantly deny the overshadowing presence of death which follows them wherever they go. Eventually, each of them goes through a journey within their consciousness, vividly visualizing a full lifetime and even lifetimes in order to be able to make the right choice. They return from their inner journeys far more conscious and this new awareness enables them to die wholeheartedly. Strangely enough, in both films the “happy ending” is death: death implies peace and understanding, harmony with life’s greater rhythms.

If we follow closely the journeys of these protagonists, we can also make use of them to reflect on our own life’s journey. Even if we don’t acknowledge this fact, death is always present for all of us, not only as some vague point down the road but as an inseparable part of life itself. We somehow have to learn to live with it. There are honest but gruesome moments in which it becomes clear to us that we are actually going to die. In such moments, our terrorized thoughts grapple with the notion of their own ending, not just the physical death but the end of our mind, our memories, and our very sense of being. How can “I’ come to an end? Can you imagine an existence without you? Our consciousness wants to persist forever. Not escaping the reality of death is therefore an awesome task.

Related to David Lowery: Every David Lowery Film Ranked

Existentialist and absurdist philosophers have asked the same questions that trouble Lowery in these films. For the German philosopher Heidegger, humans are “being-toward-death”: only humans have the distinction of standing and facing death. For the French philosopher Albert Camus, awareness of our own personal mortality is the greatest absurdity: although everyone lives as if no one knew, there are moments in which we recognize that the “tomorrow” toward which we are rushing has to be traveled to its end, where only death awaits us. We build our lives so cautiously, Camus points out, only to realize that all this building culminates in disintegration. But both Heidegger and Camus, like Lowery, arrive at the same conclusion: confronting the fact of our finitude is a fundamental key to authentic existence. When we accept that we are always on a journey toward our own death, we can also try to make meaning out of this predicament.

What will remain of us?

A ghost, so many books, and films tell us, is a sort of suspended existence, someone who died but refuses to leave because of some insatiable longing, unresolved memory, or intense attachment. Stuck in this limbo, it hovers and roams in spaces to which it no longer belongs, waiting for an experience that cannot be fulfilled. Ghosts probably represent something we can identify within our minds and hearts, what we may call a ghost from our past: our incomplete yearnings and recollections.

C., a young musician, is just about to become a ghost. Shortly before that, he and his partner, M., plan to go through a small death: moving from their rented suburban house, to which he, for reasons he cannot explain, is too attached to leave. He believes that they have a shared history there, but it is made obvious that he somehow senses the presence of his own death around him. When M. recalls how she, as a little girl, used to hide a note containing memories in every house she had to leave so that there would be a piece of her there waiting, C. wonders why she would leave all those houses and never go back. Even when he dies in a car crash, this happens just outside of the house. Soon he himself will remain like a note hidden within the walls of the house, leaving a piece of himself forgotten and waiting.

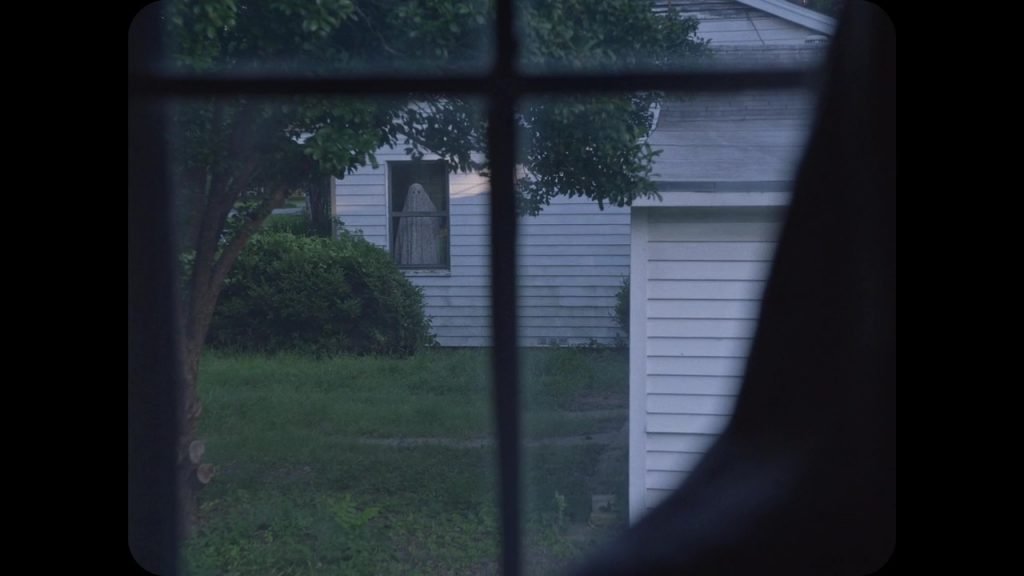

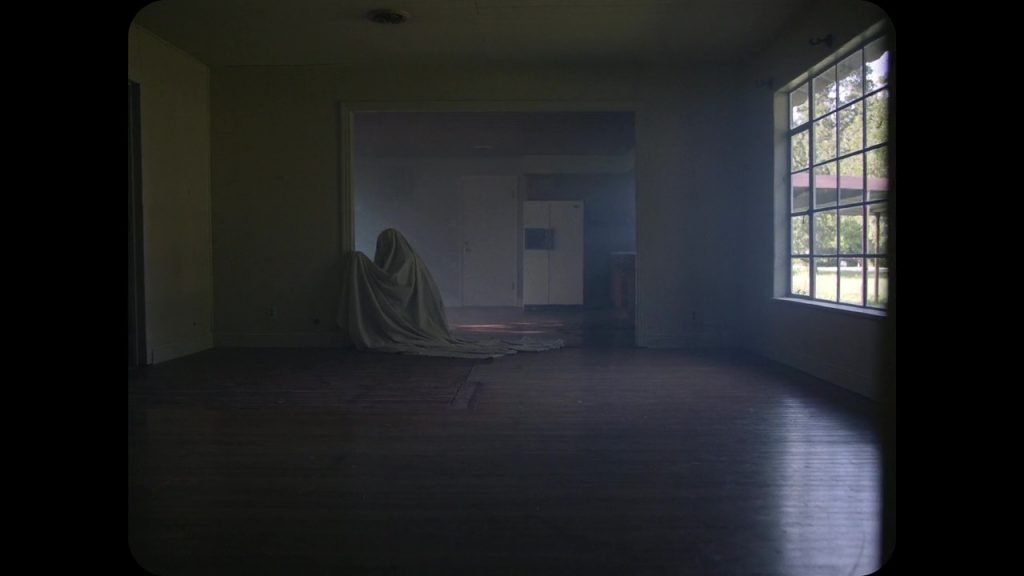

From the moment C.’s body lies in the hospital bed, Lowery forces us, the viewers, to become ghosts ourselves: long, motionless shots make us silent witnesses, just like the angels in Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire. In this way, we can identify with C., who “wakes up” in the hospital as a sheet-covered, non-existent being. The sheet’s only openings are empty, hollow eyes, shaped in a way that reflects profound sadness and longing. As C. stands up and walks through the hospital’s corridors, he refuses to leave through the gate of light which opens for him. Unwilling to fully die, he makes his way back “home.”

C.’s ghost seems so incredibly absent and yet so present. Despite his faceless witnessing, we can easily “read” his emotional experience, as he watches the grief-stricken M. devouring an entire pie only to vomit it up immediately afterward, or when he caresses her to no effect. But soon enough we will realize that the film is not about M.’s grief but about C.’s inability to say goodbye and depart from “history.” Since his entire existence has been reduced to a frozen memory, he is now stuck for eternity, while for the humans around him, chronological time continues to flow, river-like. We understand this when C. encounters another ghost sitting next to a window in a house nearby. It tells him, “I’m waiting for someone,” but when C. asks, “Who?” the answer is “I don’t remember.” This fate, the ghosts’ exile, clearly awaits him as well: turning into a pure longing without an object, an insatiable hunger reminiscent of the Buddhist hungry ghosts.

At first, he remembers what it is that he is attaching himself to. Although by now time jumps with every turn of his head, he is still enraged when he sees M. with another man, and after she leaves the house and is replaced by a small, happy family – a single mother and her two children – he throws a tantrum to make it clear that this is his house and his history. All the while he obsessively tries to extricate the note that M. has concealed from within one of the house’s walls, to feel the piece of her that she has left behind, but also to hold on to the memory of who he is waiting for.

Another turn of the head and the house becomes filled with young men and women partying, already with the awareness that the house is “haunted.” In this scene Lowery finally tells us what this enigmatic story is all about, allowing this extremely silent film to be suddenly filled with a long and dramatic speech by a young hipster. He speaks of the futility of our hope to leave something behind us that will persist even after our death, something we will be remembered for. He sounds like Camus when he says that while we “build our legacy piece by piece,” in the end, humanity will be gone, the planet is going to die, and the universe will keep expanding until it will eventually take all matter with it: “Everything you’ve ever strived for, everything that ever made you feel big or stand up tall, it’ll all go.” C. is listening intently to these words, probably reflecting on his own hopeless insistence on sticking to the physical realm and refusing to move on to a new, unknown “house.” We can surmise that Lowery is also occupied here with the dilemma of the artist, the filmmaker in his case, who strives to leave a legacy so transcendent that it will “supersede the flesh.” This is echoed in a song C. had previously composed, a song dealing with sudden death and abandonment, which is probably the piece that is left of him in this world.

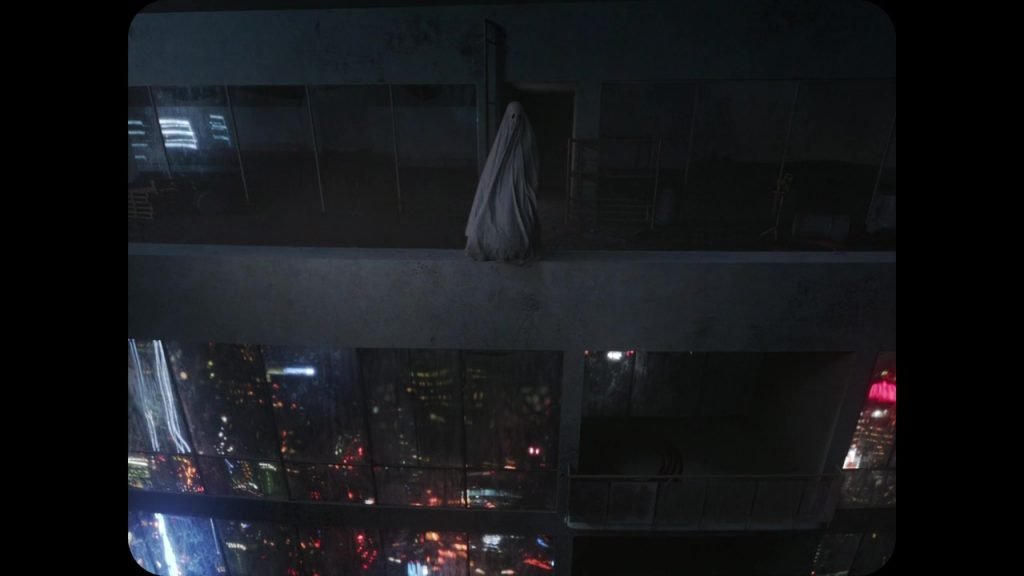

But despite his reaction to the hipster’s speech, C. won’t let go. How could you release a memory which is the only substance you are made of? Just as he finally gets hold of M.’s note, the house, as well as the house nearby, are torn down by bulldozers, leaving both ghosts with nothing to hold on to. For the other ghost, this means redemption: as soon as it recognizes that “I don’t think they’re coming,” it is freed from the torturous waiting of which it was made and vanishes into thin air. Even this is not convincing enough for C., who continues to roam the skyscraper which has been built upon the ruins of the old houses. Like the deathless robot boy David in Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence, he commits an impossible suicide by throwing himself off a building. And like David, he is eternally caught within his own circuit of memory.

With the fading away of M.’s memory, C.’s only anchor is the history of the house. This is why his failed suicide takes him back in time, all the way to the initial foundation of the house when the first settlers came to the area. Like C., the viewer becomes caught in this maze of time and space, silently witnessing a hopeful family of settlers and noticing how one of the children sticks her own note under a stone. Like everyone in this story, she represents the desperate human struggle to keep a memory alive within the perpetual torrent of time and to declare one’s existence in the emptiness of the cosmos. But soon after, the entire family perishes in an Indian attack, and the exhausted C. observes the girl’s rotting corpse, and later the remaining skeleton.

Another jump in time and C.’s ghost finds itself in the newly built suburban house, a moment before the living C. and M. enter to examine the space. Now the ghost has an opportunity to relive the entire history of the relationship in this house. We notice that the living C. senses a familiar presence between the walls, the presence of his own unavoidable death, and we finally understand that the weird noises the couple had been hearing while they lived in the house were coming from C.’s very own ghost. They too are trapped in this vicious circle of time, in which the dead are alive and the living is already dead.

Also Read: A Ghost Story (2017): An Existential Poetry on Featherbed of Grief

When the ghost hears his living self at night whispering to M. that he feels ready to leave the house, he realizes with great despair that this is the end of the house’s story as well as the end of his pursuit in the physical realm. He is going to be deserted for the second time. Only this time he doesn’t neglect his unfinished business: while watching the inexperienced version of his ghost-self witnessing M. leaving, he breaks the circle of time by reaching for M.’s note and reading it. What exactly is written in the note matters very little, and Lowery leaves it concealed for a good reason. It is the act itself that is enough for C.’s mature ghost to be reminded of what was but is no longer here, and with this total recognition of finality, he can die consciously, this time without leaving a piece of him in time and space.

“Green is what is left when we die”

The Green Knight appears to be an altogether different allegory, dealing with its own meta-theme. Loosely inspired by the late 14th-century Middle English chivalric romance, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, it indeed raises the extremely broad tensions between our arrogant human culture and nature, and our transcendental religions and paganism. After all, the green knight is a personification of nature, guided by the sorceress Morgana to challenge King Arthur’s men on Christmas Eve. However, in Lowery’s hands, the story becomes a process of preparation for a mature and humble recognition of one’s own finite existence.

Lowery’s Gawain is a young would-be knight, the son of King Arthur’s sister Morgana, who feels too childish to take on the responsibilities of knighthood. His mother devises a magical event – conjuring the green knight – to force Gawain into manhood by leading him through a frightening initiation. She creates the perfect setting to evoke in her son the unexpected readiness to volunteer for the green knight’s “friendly Christmas game.” The game invites a willing man to strike the green knight with his own ax and, in return, to receive an equal blow a year later in the green knight’s forest church, the “green chapel.”

Whether Morgana’s plan goes wrong is unclear, but the green knight offers his neck for decapitation and Gawain cuts off the head, believing, like everyone else in the hall, that he has triumphed and demonstrated the courage befitting a knight. But the green knight, being ever-renewing nature, life and death in one, instantly comes back to life, announcing that a year from now, the mortal Gawain will be likewise beheaded. While Gawain harbors the hope that this is all a game, both Arthur and Morgana understand that the young man will be facing death as a master: Morgana prepares for Gawain an enchanted protective green belt to prevent actual harm and Arthur encourages him to act as any real man would and to march up to “greet death before his time.”

Lowery’s vision of Gawain’s journey a year after, which expands the original poem, blurs the border between inner and outer to signify that this is, after all, a journey into consciousness or, more accurately, into the subconscious. Harrowing sights of death welcome Gawain as he travels deeper into the forest, where nature’s domain robs humans of control and grasp. As a scavenger tells Gawain while merrily walking in a corpse-choked battlefield, “nature will do its trick. She’ll suck ’em in and tuck ’em tight.” In this intensely subjective vision, everyone around him seems to represent either the green knight or Gawain’s innermost being or both. When the scavenger and his gang steal Gawain’s protective belt and the green knight’s ax and leave him bound hand and foot, Gawain asks, “Is there really a chapel?” to which the young robber replies, “You’re in it.” Utterly defenseless, Gawain is compelled to confront his own cessation for the first time: for a moment, Lowery shows us that all that remains of him is a naked skeleton.

From now on, the young Gawain seems to hover between existence and non-existence. He is a silhouette, a reflection in the water, or a vague figure shrouded in thick fog. It seems almost obvious that his next station would be an encounter with a ghost, Lady Winifred, who has lost her head in the spring. Just like her, Gawain’s head might look like it is on his neck, but it is not. And when he wonders whether she is real or a spirit, she answers, “What is the difference?” But Winifred, like the scavenger before her, is also an ambassador sent by the forest’s spirit to test Gawain’s chivalry – his kindness and selflessness: when he returns Winifred’s head to its place, the stolen green knight’s ax miraculously reappears.

Gawain’s dark night of the soul only continues to unfold: the token given to him by his loved one Essel is torn from his neck, and his human figure is further dwarfed by the overwhelming presence of mythical giants. His only relief is a fox that escorts him, possibly as an expression of his self-protective impulse, and a castle whose inhabitants – a Lord, his Lady, and a mysterious old woman – welcome him with open arms. They may be representations of King Arthur, Gawain’s lover Essel, and his mother, and are perhaps nothing but a vision invoked by Morgana from afar, since the Lord tells him when he departs, “If you come back by this way again, we shall be gone!”

Also Read: The Green Knight (2021): The Cyclic Battle Between Rot and Growth

Whether real or unreal, the castle’s Lady challenges Gawain in many ways. She draws a portrait of his shadow self, and erotically tempts him into begging to retrieve the stolen magical belt only to humiliate him by saying, “You are no knight!” But most significantly, an articulate speech by the Lady, just like the hipster’s speech in A Ghost Story, finally discloses to us what The Green Knight is all about. We hear that green is the “color of living things, of life,” but also of rot and decay. In our pursuit of red – lust, ardor, and passion – we, humans, do our best to scrub out the green when it “comes creeping up the cobbles” or “blooms beneath our skin.” But even when we pull it out by the roots, it returns to creep in around the edges, and remains when passion dies: “When you go, your footprints will fill with grass… All you hold dear will succumb to it.” Gawain is no doubt craving the red of honor and power; he still hopes to come back as a respected knight to an admiring kingdom, and for this reason, he determines to cling to his belt when the green knight’s ax strikes him.

When he eventually enters the green chapel, he finds the green knight serenely asleep as if he were an ancient tree. He is therefore compelled to sit at his feet and to submit himself to his mighty presence. As the green knight opens his eyes, several of the story’s characters are reflected in them, including Gawain’s own eyes, since the green knight is the beginning and the end of all stories, all of life as well as death’s final blow. If Gawain faces anyone, it is his own face and his own noble choice embodied. Can he offer his neck now? Is he ready? He is not: instead, he flinches and asks the Lord of Life and Death with existential horror, “This is really all there is?” In return, he receives the disturbing question: “What else ought there be?”

In the same way that C.’s ghost transcends time and space through an inner vision whose purpose is to redeem, Gawain sees before his mind’s eyes a full, alternative lifetime unfolding, which is reminiscent of the optional lifetime Jesus, in Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ, is given just before making his final act of self-sacrifice. The allusion to this film’s unforgettable ending should not surprise us, because Jesus and his promise of eternal life are present in this film too, only here it is not the wish for immortality that comes out victorious but the acceptance of one’s mortality, the green, the “way of all flesh.” Still, for a long moment Gawain escapes in his mind to the red: Owing to the belt’s protective power, he returns to Camelot and is enthroned by the sickly Arthur as the new king. Essel secretly bears his child, but in the name of his status, he abandons her, takes the child away from her, and marries a noblewoman. For a brief moment it seems as if he has cheated death, but then, as he becomes the living expression of the portrait of his shadow self, everything starts to go downhill: he loses his son in battle, becomes humiliated by the crowds, and years later, when his castle is under siege, he is abandoned by his entire family. At that point, Gawain realizes that all he has done is to deny and postpone an unpreventable reality that was constantly knocking on his doors; he thus removes the green belt to allow his head to fall onto the ground.

Recommended: The 30 Best A24 Films

“Now I’m ready,” he announces after the vision has dissolved, removes the magical girdle, and prepares for the green knight’s ax. He is congratulated by the Lord of Life and Death, who has no intention of sparing him, for his emergence as an authentic knight. It is significant to understand that Lowery departed here from the original poem, in which Sir Gawain doesn’t take off the belt, remains unharmed, and returns home shamefully. Since Lowery’s interest is not in a moral tale of integrity and honor, but in the mature recognition of our finitude, what really matters is Gawain’s willingness to embrace his fate, just as the dissolution of C.’s ghost is considered a happy ending.

This is the repeated, uncomfortable message that Lowery finds so urgent to convey. We may feel that this message – that everything we hold dear will vanish at the end of time or that the grass will cover our dissolving footsteps – is pessimistic or even tragic. But Lowery makes it clear in interviews as well as in the general tone of these films that for him, this is optimistic and peaceful learning. Like the existentialists, who are convinced that an unwavering confrontation with our finite existence can release immense positive powers from within us, Lowery seems to believe that this is an important key to finding our place in the universe.

![I Am Mother Netflix [2019] Review – A Slick but Underwhelming AI-Themed Thriller](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/I-Am-Mother-Netflix-highonfilms-768x448.jpg)