Although it is not normally the case with short films, in the rare case of “Camping in Paradise,” it feels as though the movie would work a lot better if it were a feature-length film instead of a short one. The main problem with this Eirik Tveiten directorial is its surface-level tackling of the themes it sets out to explore. It becomes clear within the first few minutes what the film is trying to say, and while that in itself is not inherently bad, the lack of layering makes the message feel too simplified for its own good.

A philosopher named Christian (Espen Alknes) and his girlfriend Pernille (Oddrun Valestrand) are compelled to spend a night at a nudist campsite. From the very moment this premise unfolds, it is obvious that nudity is meant to serve as a metaphor for freedom. Freedom from judgment, societal norms, pretenses, and perhaps even one’s own inhibitions. This setup has a lot of potential. It is playful, slightly provocative, and thematically rich, but Tveiten’s handling of it leaves little room for the audience to engage or interpret. Everything is told to us instead of shown.

Now, this is not exactly a bad thing. The metaphor of nudity equating to liberation can be powerful if treated with nuance and patience. However, what doesn’t work here is the subtlety of a sledgehammer with which the message is presented. Tveiten, who has also written the short film, seems far too determined to hammer in his ideas to the point that the film appears contrived rather than organically impactful.

Lines like “There is nothing to hide behind your Gucci glasses here” and “Nudity refers to freedom” are not only on-the-nose but also rob the audience of the joy of discovery. The film feels as though it’s constantly shouting its message at you instead of trusting the viewer to piece it together.

This brings me back to why “Camping in Paradise” could have worked so much better as a feature-length film. Firstly, a longer runtime would allow the director to flesh out the central message, i.e., the idea of nudity as a symbol of emotional and psychological liberation, in a way that doesn’t feel forced. There’s a fascinating duality at play here: nudity as vulnerability, and nudity as empowerment. A feature film could have explored that tension more meaningfully, allowing space for introspection and subtle character development instead of relying on expositional dialogue.

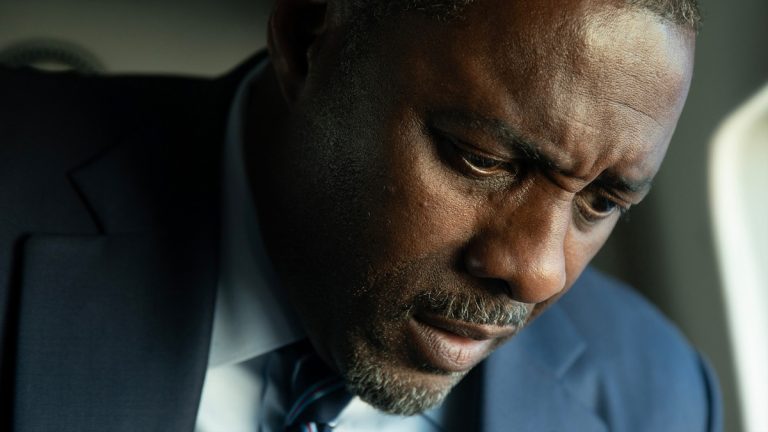

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, a feature-length version would give us time to actually live with these characters. We barely scratch the surface of who Christian and Pernille are as individuals. Why is Christian, often referred to as “Plato” by others at the campsite, a man of few words, so restrained and seemingly uncomfortable in his own skin? Is it because of philosophical rigidity, emotional repression, or simply a fear of appearing foolish?

Similarly, Pernille’s carefree, vibrant nature is briefly touched upon, but we never quite understand what drives her or what she’s seeking from this experience. Their dynamic, the stoic thinker versus the free-spirited partner, could have been a fascinating study in contrasts if given time to breathe.

The supporting characters, Viggo (Stig Henrik Hoff) and Jenny (Mona Grenne), also feel underutilized. They are clearly designed to act as catalysts for Christian’s transformation as they act as embodiments of the liberated world he’s afraid to join. However, the short film never gives them enough dimension. In a longer format, these interactions could have been rich, layered exchanges that gradually push Christian toward self-realization.

The transformation does happen here, but frustratingly, it occurs just when the film is about to end. The moment we finally start empathizing with Christian, understanding his discomfort and the internal weight he carries, the credits roll. It’s a narrative tease. The emotional payoff arrives, but only fleetingly.

Also Read: 10 Great Horror Movie Protagonists of All Time

And then comes the ending, where the film’s problems truly amplify. Given the film’s overall tone – quiet, slightly restrained – which is tinged with philosophical undertones and wholesomeness, one expects a warm, reflective conclusion. From the fifth minute itself, it’s easy to predict that Christian will eventually let go of his shame and embrace nudity, symbolizing his acceptance of freedom. That moment indeed happens, but the journey leading to it takes an unnecessarily erratic turn.

Christian’s sudden argument with Pernille feels tonally misplaced, almost jarringly so. It’s as if the film momentarily forgets its own rhythm and tries to inject artificial conflict. Following this is a comedic sequence that feels out of sync with everything that came before. Instead of deepening the emotional weight, it undercuts it. The tonal inconsistency not only dilutes the film’s message but also leaves the audience unsure of what to feel, as in, should we laugh, reflect, or cringe? The awkward humor feels forced, and not in a self-aware or intentional way.

Still, the ending brings Christian’s long-awaited transformation. He finally embraces the freedom he’s been avoiding. On paper, this should feel cathartic, but because of the inconsistent tone preceding it, the resolution feels somewhat hollow. The film’s heart is in the right place, but the execution stumbles just when it matters most. And all that remains is a faint aftertaste of what could have been a genuinely moving exploration of vulnerability and liberation.

However, credit where it’s due. Just having the audacity to present nudity as a metaphor for freedom in a short film format is commendable. Many filmmakers would shy away from tackling such a subject for fear of being misunderstood or labeled as provocative for the sake of it.

But Tveiten treats nudity with respect, framing it as an inherent part of the film’s world rather than a spectacle. The way he and the cinematographer, Torstein Nodland, compose their shots deserves praise. From the very first frame, the film makes you comfortable with the idea that the human body is not something to be censored or ridiculed but simply seen as it is, which is natural and unembellished.

The camera placement throughout the film ensures that the nudity never feels exploitative or titillating. It’s neutral and almost observational. The cinematography aligns with the film’s intent, i,e, to normalize, not sensationalize. In fact, the visual language often does a better job of conveying the film’s themes than its dialogue. The serene campsite setting, the earthy color palette, and the natural light all add to the film’s grounded texture. There’s a quiet beauty in how Tveiten captures human vulnerability against the backdrop of nature; you just wish the writing had been as patient as the visuals.

“Camping in Paradise” is, at its core, a film that wants to liberate its characters, and by extension, its viewers, from the weight of societal pretense. It wants to say that true freedom lies not in what we wear or project, but in our ability to simply exist without judgment. That message, though familiar, still holds relevance in today’s world. It’s just that the delivery here feels rushed and overstated.

Maybe someone should genuinely send Tveiten an email suggesting he turn this short into a feature film. Because the foundation is solid, the themes are worthwhile, the performances are engaging, and the direction is confident. All it needs is more time to breathe, more space to explore the nuances it currently only hints at. In its current form, “Camping in Paradise” feels like a sketch of a much better painting waiting to happen. And who knows, with the right runtime and refinement, it might just turn into something totally fresh and peerless.

![Village of the Damned [1995] Review: Pointless Remake](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/village-screenshot-1-768x320.jpg)

![Paths of Glory [1957]: An Anti-War Anthem](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/paths-of-glory-768x432.jpg)

![The Fiances (I Fidanzati) [1963] Review – Love Lingers in a Parched, Industrialized Land](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/The-Fiances-1963-768x432.jpg)