Ex Machina (2015) Movie Explained – Ending & Themes Analysed: If Alex Garland sticks to his word about his next feature film being his last one, it’ll be a disappointingly short albeit extremely fruitful career as a director. There’s no more significant proof of that than his 2014 debut as a feature filmmaker with ‘Ex Machina’. Starring Domnhall Gleeson, Alicia Vikander, and Oscar Isaac, it shows a keen directorial eye possessed by a man who was previously known for his screenwriting credits and being a published author. Set in a frigidly minimalistic world of sharp lines and expressionistic lighting, Garland packages the age-old ‘fate vs. free will’ debate in a sci-fi story that is both inventive yet feels familiar; harkening back to his screenplay adaptation of Ishiguro’s ‘Never Let Me Go.’ As far as debuts go, it is masterful in its controlled ability to tell a story that visually dazzles while conveying extremely loaded philosophical ideas.

Ex-Machina Plot Summary & Movie Synopsis:

Caleb Smith is a talented programmer employed by Blue Book, the world’s largest internet search engine company. He wins a contest in which the prize is that he gets to spend a week at the home of the company’s elusive founder and CEO, Nathan Bateman. Nathan lives alone, isolated from the rest of the world and consumed by his work. It’s a golden opportunity for Caleb as he states that Nathan’s abilities are akin to Mozart’s in their prodigious ingenuity since he wrote Blue Book’s base code at the age of 13. At Nathan’s home, Caleb finds out that the former has no interest in a formal employer-employee relationship but wants them to bond like two friends having a gala time together.

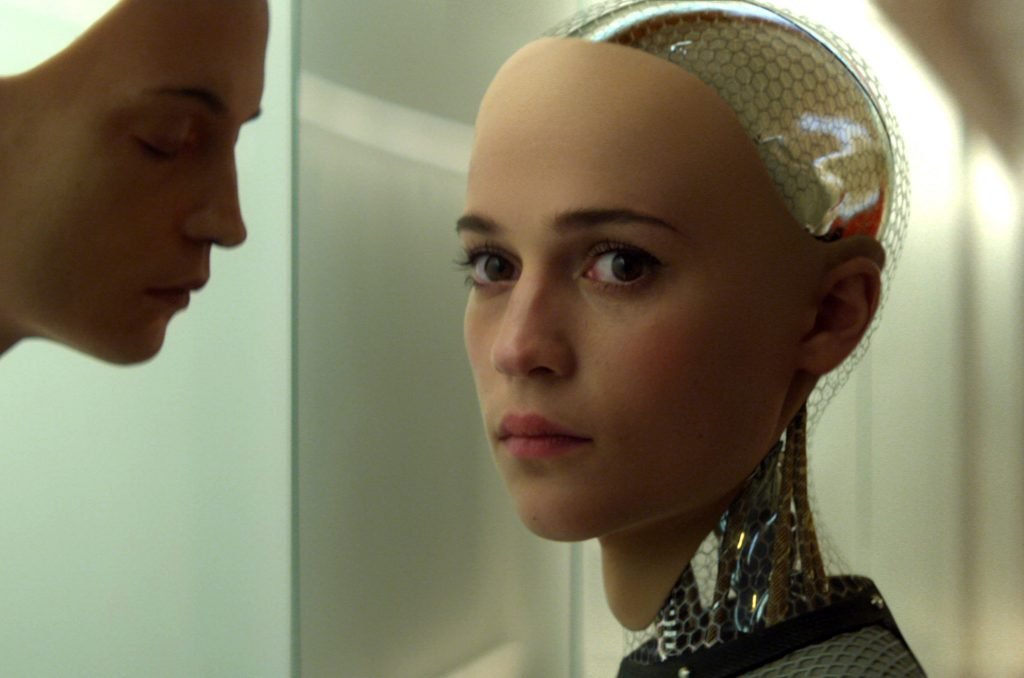

There is a specific purpose to Caleb’s visit, though, and it’s that he has to be the human component in a Turing Test involving an A.I. that Nathan has created. The subject, named Ava, has a human face. Still, an otherwise mechanical body is essential to the test as Nathan isn’t simply trying to determine whether people can be deceived into believing that Ava is a robot but to let them know that she is and still makes them overlook the fact because of how real she is. Caleb and Nathan’s conversations range from discussing the possibilities of A.I. to discussions on free will, gender, art, creativity, and even religion. As the progress and time of the test passes, Caleb starts to discover a sinister side to Nathan while also finding himself attracted to Ava.

What does ‘Ex Machina’ mean?

The term ‘Deus ex Machina comes from Greek theatre and is a literary device. It means ‘god out of the machine’ and refers to a character playing God, being lowered onto the stage using a crane to resolve a conflict. The plot device helped in unpredictably settling what otherwise seemed like an irresolvable issue, generally towards the end of a play. The film’s name removes the word ‘Deus’, which means God, from the term. This is a reference to Nathan’s creation of Ava and, therefore, at playing God, which undermines the role of God in favor of human creation and therefore shows a world where God is increasingly made irrelevant as attempts to supersede his creations are being made by humans, through the use of machines. The name is a literal borrowing of the term and its manipulation, as at the end of the film, it is the intervention of a machine that resolves the plot from its deadlock once Nathan reveals his knowledge of Caleb and Ava’s subterfuge.

Ex Machina Movie Theme Explained:

Creation and playing God

Nathan’s house is set amidst a lushly green landscape, a world that seems to have been spared the touch of humans. Within this Edenic paradise, he is operating a subterranean research facility where he’s attempting to create what would one day render life itself, something the space surrounding his facility epitomizes, completely unnecessary. Garland, therefore, plays with the dichotomy of human and natural creation from the offset. Ava is Nathan’s creation – that’s the crux around which the entire film revolves. She can express seemingly real human emotions and interact in a way a real human being would, socially. She, therefore, represents the pinnacle of human creation. In Nathan’s eyes, her creation wasn’t a decision that he consciously made but came about as the next step in human evolution. Therefore, what we observe from the get-go is a conflict between nature and man in which Nathan sees himself as being God.

He is completely enamored of Caleb from the moment he calls Nathan’s creation akin to something that shouldn’t be associated with human history but the ‘history of gods’. He then goes on to manipulate these words to make it seem like Caleb actually called him ‘God.’ Garland keeps resorting to language as the means of depicting Nathan’s gargantuan ego. When Nathan asks why he was selected, Caleb tells him that based on his performance and skillset, he was ‘chosen’, a term that instantly demonstrates the power dynamic between them while also making it seem like Caleb is some sort of prophet chosen by a godlike being, to carry out his wishes. Caleb’s admiration of Nathan, devolving into fear and contempt, is also achieved through language. From his assertion of Nathan’s work as being part of the ‘history of Gods’, Caleb turns to quote Oppenheimer’s justification of his creation from the Bhagavad Gita, ‘I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds’, stating his recognition of Caleb’s destructive tendencies.

Robots and Sexuality

Nathan’s delusion spills into the realm of gender fairly early. From the moment he starts viewing himself as God in front of Caleb, male delusion surfaces. For him, belonging to sex that cannot biologically reproduce, the act of creating a sentient lifeform is the equivalent of a godlike act as it subverts nature’s dictates. Then comes Nathan’s flagrant sexism. He employs a Japanese woman, Kyoko, who doesn’t speak a word of English and whose attractive qualities clearly play a part in her employment. As Caleb starts to get germane to Nathan’s deception, he asks him why he made Ava female since a robot doesn’t need sex. Nathan starts with a tautological explanation about sex being related to social interaction before resorting to an inane justification about how if one has life, they might as well enjoy it, which is facilitated by the possession of sex and sexuality. To that extent, Ava has apparently been equipped with genitals that respond to sexual pleasure, but he denies ever having engaged in a sexual interaction with her on the grounds that he shares a paternal relationship with her.

This perverted approach of Nathan soon unravels the real purpose behind Ava being female – to disarm Caleb and make him more susceptible to believing that Ava is human. She is ‘the magician’s hot assistant,’ the distraction that keeps one from judging the A.I. itself completely rationally. Her face happens to be a composite of Caleb’s preference for women in the kind of pornography he consumes. Caleb turns out to be the perfect test subject as his sensitivity, and lack of an emotional retreat makes him easily susceptible to Ava’s manipulation, something that was programmed into her while also finding himself attracted to her physically. This expresses itself in the form of his micro-expressions and his voyeuristic monitoring of Ava when they’re separated. Even though Caleb’s responses to Ava are automatic, they still depict an underlying inhibition in both men. They’re both involved in science, and its usage for human advancement yet are prohibitively vulnerable to their own sexual desires.

What is the crack on the glass wall?

When Caleb first meets Ava, he notices a crack in the glass wall separating the two of them. He is confused by this distortion in the midst of everything else that seems so glacially perfect. He punches the mirror in his room to express his frustration. Towards the end of the film, Caleb discovers that there were multiple prototypes before Ava who were all destroyed or succumbed to their burning desire to escape. As he finds out that Kyoko too is an android, he starts questioning his own sanity and cuts himself to see if he too is an android with planted memories. He starts to bleed profusely and realizes he’s human, and that strengthens his desire to help Ava escape.

A key question related to Ava, as exemplified by the chess computer problem, is if she can express real emotions or does she just simulate them? While no clear answer is provided, the crack on the wall becomes a lateral hint at the fact that she can. Like Caleb, she too must have punched the wall at some point out of frustration at her captivity and maltreatment by Nathan. Therefore, the cracks on the wall become symbolic of the characters’ recognition of Nathan’s wickedness which then sets off their pursuit of liberating themselves. The fact that they appear as anomalies in surroundings designed to have a painstaking degree of orderliness emphasizes the vehemence of their disaffection.

Ex Machina Movie Ending Explained:

On their final day, Nathan reveals to Caleb that he’s been monitoring his secret conversations with Ava during the power cuts all along using a battery-powered camera. Caleb testing Ava was never the real test, but the other way around – Caleb was to be the subject of Ava’s manipulations, and if she succeeded in gaining his trust, it would depict that she has real intelligence. At this point, Caleb tells Nathan that he was aware of the latter’s surveillance in some capacity and therefore had reversed the security system the previous night when Nathan was drunk. Nathan angrily knocks Caleb down. As Ava escapes, she meets Kyoko, and the two of them are attacked by Nathan. He manages to disable Kyoko, but Ava kills him. Following this, she borrows skin and hair from previous android prototypes to take on the guise of a real human being. When Caleb finds himself locked, she doesn’t help him in escaping but instead escapes the facility herself, taking the chopper meant for Caleb to return. As she finds herself amongst other human beings, she seems disenchanted before turning back.

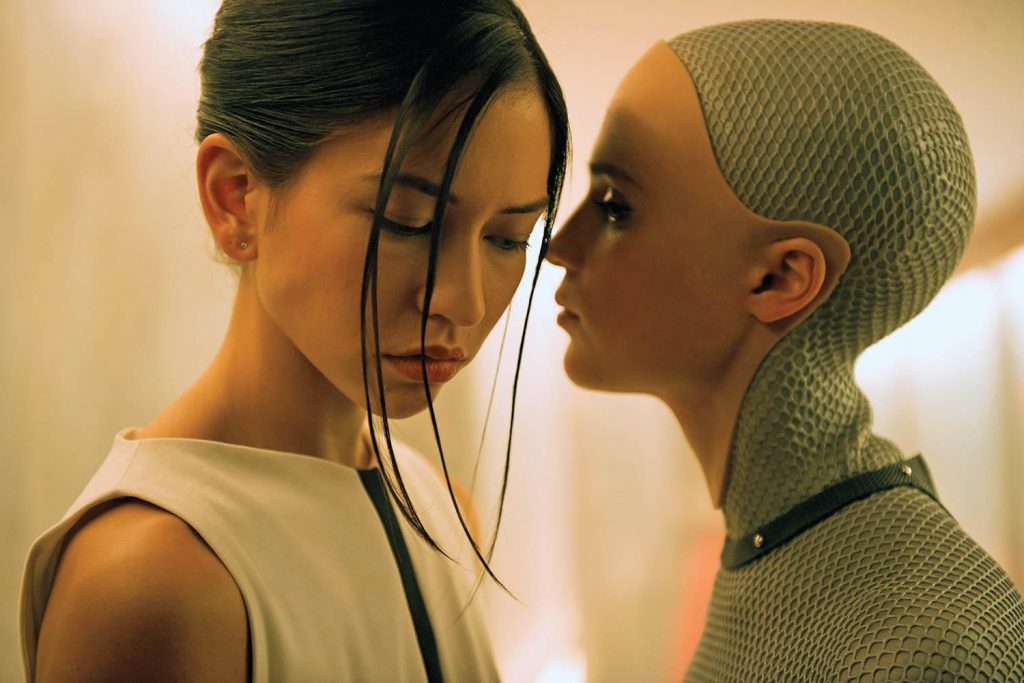

What does Ava say to Kyoko?

Ava’s undisclosed words to Kyoko are the only time we see two women interact in the film. Following this, the two engage in combat against Nathan, and Ava kills him. There’s a parallel here to Virginia Woolf’s argument in ‘A Room of One’s Own’ about women requiring a creative space of their own to express themselves, devoid of patriarchal intrusion and restriction. Similarly, the first time the two robots meet each other, enslaved in their own ways by their master, they temporarily create a space where they subvert what they were programmed to do by their creator and end up killing Nathan, who taught them to seek freedom while prohibiting them from doing so. It’s the interaction between the two that aids this, hence bringing to a head Nathan’s depravity and providing the two with retribution against that alongside freeing themselves from him. Ava’s words to Kyoko were possibly her trying to convince Kyoko to join her in her escape from the facility. This sadly doesn’t happen, but at least Kyoko’s purpose is toppled by her perverse subservience under Nathan while the act of killing Nathan becomes part of Ava’s designed purpose, something he surely didn’t intend in his otherwise extremely calculated approach.

Why does Ava turn back?

In Nathan’s words, Ava is a ‘rat in a maze. She has been programmed to use her intelligence as a means of staging her escape. She succeeds in doing that, which is why one of the few prominent expressions of emotion from her is when she is elated at the prospect of finally seeing the world outside the laboratory. She had initially mentioned to Caleb that if she ever got to see the outside world, she’d go to a road intersection, which is exactly what she does. Yet, in doing this, Ava both performs what she was created to do and what she desires to do. So she can no longer move forward, and all she can do is go back, possibly to the facility, and in there, free Caleb. The film’s ‘fate vs. free will’ argument reaches its climax here as she has accomplished both purposes and now has become, in effect, purposeless.

It’s important to note here that there isn’t an emotional aspect to Ava’s abandoning Caleb, and therefore, there is no spite or sense of revenge against humanity in it. Nathan had stated that the robot that would follow Ava would be the perfect one, and this is proof of that – Ava has no real feelings and can only simulate them to achieve her ends. For her, Caleb was a tool and no more than that, and so she didn’t free him as taking that extra step would make her actually sentient. It also ties back to Caleb’s explanation of the thought experiment, ‘Mary in the black-and-white room’, which tries to determine if someone possessed with precise theoretical knowledge but no experience of it is capable of adapting to the reality of what they know as well as going beyond their knowledge. Ava, not being a real human being and devoid of any real thoughts or feelings, cannot gain anything from the world outside except some kind of mechanistic closure at having achieved her goal, which in this case, was to escape.

![The Story of Southern Islet [2021]: ‘Locarno’ Review – Malaysian ghost-tale conjures an enchanting spell](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/The-Story-of-Southern-Islet_6-768x512.jpeg)