Paul Schrader has long been drawn to the inward collapse of men caught in cycles of repression, isolation, and self-denial. But with “First Reformed” (2017), he pushes that exploration into uncharted territory—into the theological realm. Here, masculine angst meets religious austerity, and the result is a devastating psychological portrait of a man gripped by a crisis of faith.

From global ecological despair to the ghosts of personal trauma, the film tracks Reverend Toller’s descent as he tries, quietly and desperately, to locate himself in a world that feels increasingly hollow. Make no mistake: “First Reformed” is a psychological thriller—taut, meticulous, and quietly combustible. But its intensity doesn’t lie in dramatic reveals. It pulses instead through conversations, diary entries, and the lonely rituals of daily life. This is a film of restraint—emotionally, visually, theologically.

Nominated for Best Original Screenplay at the 91st Academy Awards, the film is layered and demanding. To explain it is not to over-analyze its ambiguity but to immerse ourselves in what it deliberately offers—and withholds. Much of its power hinges on Ethan Hawke’s masterful performance, which earned him Best Male Lead at the 34th Independent Spirit Awards. But beyond the performance lie unanswered questions, unspoken tensions, and gaps that feel very much intentional.

This piece is our attempt to sit with those questions and to unpack the narrative’s deeper structure and thematic intricacies.

First Reformed (2017) Plot Summary and Synopsis:

Why does Reverend Toller start writing a journal?

The film opens with a solemn image of the First Reformed Church in Snowbridge, Albany County, New York. Within the modest walls of this old Dutch Reformed congregation, Reverend Ernst Toller embarks on an experiment: he begins writing a handwritten journal of his daily activities, raw thoughts, and unfiltered opinions. He resolves to continue this practice for twelve months. After which he will destroy the diary by fire. Built in 1767 at what was once a stop on the Underground Railroad, the church is now barely afloat, sustained through its acquisition by Pastor Joel Jeffers of Abundant Life, a thriving evangelical megachurch that handles the logistics and funding.

What does Michael reveal about his worldview?

One Sunday, after the service, Toller is approached by a quiet parishioner named Mary Mensana. She privately asks him to meet her husband Michael, a radical environmental activist recently released from jail in Canada. Michael, she explains, is deeply disillusioned by the state of the world. She’s pregnant, but Michael is disturbed by the idea of bringing a child into what he sees as a doomed planet. Hearing her concern, Toller agrees to visit them at their home.

There, Toller and Michael engage in an intense, soul-baring discussion. Michael is unwavering in his belief that climate catastrophe, corporate greed, and ecological collapse are rendering the world unlivable. In such a grim future—where activists are either jailed or murdered—he can’t justify raising a child into false hope and inherited helplessness.

In response, Toller opens up about his own past. Following family tradition, he served as a military chaplain. However, when his son Joseph, whom he had encouraged to enlist, died in the Iraq War, he was consumed by guilt. His wife left him, and he abandoned the military. Only then did he begin his service at First Reformed. He tries to explain—plainly, quietly—the delicate balance between despair and faith. He offers to help Michael find the strength to live with his disillusionment. They agree to meet again the next day. That night, in his journal, Toller confesses he held something back: the belief that despair, at its core, is man’s vanity—a refusal to accept God’s transcendent creativity. It didn’t feel right to say aloud.

What does Toller learn about Michael’s plan?

The next day, a small group of tourists visits the church, and Toller gives them a tour. He shows them the historic artifacts, the souvenir shop, the broken organ at the pulpit. Later, he’s summoned by Pastor Jeffers at Abundant Life, who reminds him about the fast-approaching 250th Reconsecration ceremony. When asked about preparations, Toller admits there’s been little progress. Jeffers gently prods him to reach out more, reminding him that even pastors need pastors.

On his way out, Toller receives a message from Mary: Michael has postponed their meeting due to work. Before heading back, he has lunch with Esther, the choir leader from Abundant Life, who cares deeply for Toller and wants to support him through his physical and emotional deterioration. But Toller, stubborn and inward, keeps her at arm’s length.

Later, Toller visits Mary at home. She leads him to the garage and shows him a chilling discovery: Michael had been building a suicide vest. She’s not afraid for herself or their unborn child. She’s terrified of what Michael might do to himself. Toller takes the vest and promises to dispose of it, agreeing not to involve the police out of fear it might push Michael further over the edge. That night, in his journal, he muses on discernment—how people often confuse chasing emotions with seeking real experience.

How does Michael’s death affect Toller?

The next morning, a music company arrives to repair the church’s broken organ. Afterwards, Toller visits Abundant Life again and is unnerved by the extreme views expressed by some of the young congregants about religion, violence, and the world. He mentions this to Jeffers, who cynically remarks that “Jihadism is everywhere these days.”

Soon after, Toller receives a message from Michael to meet at Westbrook Park. When he arrives, he finds Michael’s lifeless body—his head blown apart by a shotgun. The police treat the death as a clear-cut case of depression-induced suicide. Toller asks Mary if she had been an activist, too. She admits to sharing Michael’s beliefs but clarifies that she believes in life, not death. Per Michael’s final wish, a memorial service is held at a toxic-waste landfill, where his ashes are scattered as Esther’s choir sings an environmental protest song.

The next day, Toller attends a lunch at a local diner with Pastor Jeffers and Edward Balq, a major funder of Abundant Life and the CEO of Balq Industries. Balq has taken a personal interest in the Reconsecration ceremony. He confronts Toller over Michael’s memorial, accusing him of politicizing the church and dragging Abundant Life into controversy. Their conversation quickly turns into a heated argument over climate change. Balq brushes it off as “complicated,” while Toller insists it’s a moral issue of Christian stewardship. Balq leaves, disgusted, calling Toller a failure who couldn’t even save a lost soul.

The next day, Mary asks Toller to go on a biking trail with her. Afterwards, he helps her pack up Michael’s belongings—his memory now a constant ache. Sinking deeper into despair and drinking heavily, Toller finally visits a doctor, who suspects stomach cancer and schedules further tests. Esther, concerned, confronts him about his health, but Toller lashes out, telling her he despises her for being a mirror of his failures.

What does Toller discover about Balq Industries?

Alone, Toller begins going through Michael’s laptop—something he had hidden from the police to protect Mary. On it, he finds damning information about Balq Industries and their devastating environmental footprint. Wracked by illness and disillusionment, Toller begins to unravel. He reconstructs the suicide vest, never having disposed of it like he promised.

Also Read: First Reformed Review [2018]: Spiritual Collapse under Crisis of Faith

First Reformed (2017) Movie Ending Explained:

What happens during Mary and Toller’s final interaction?

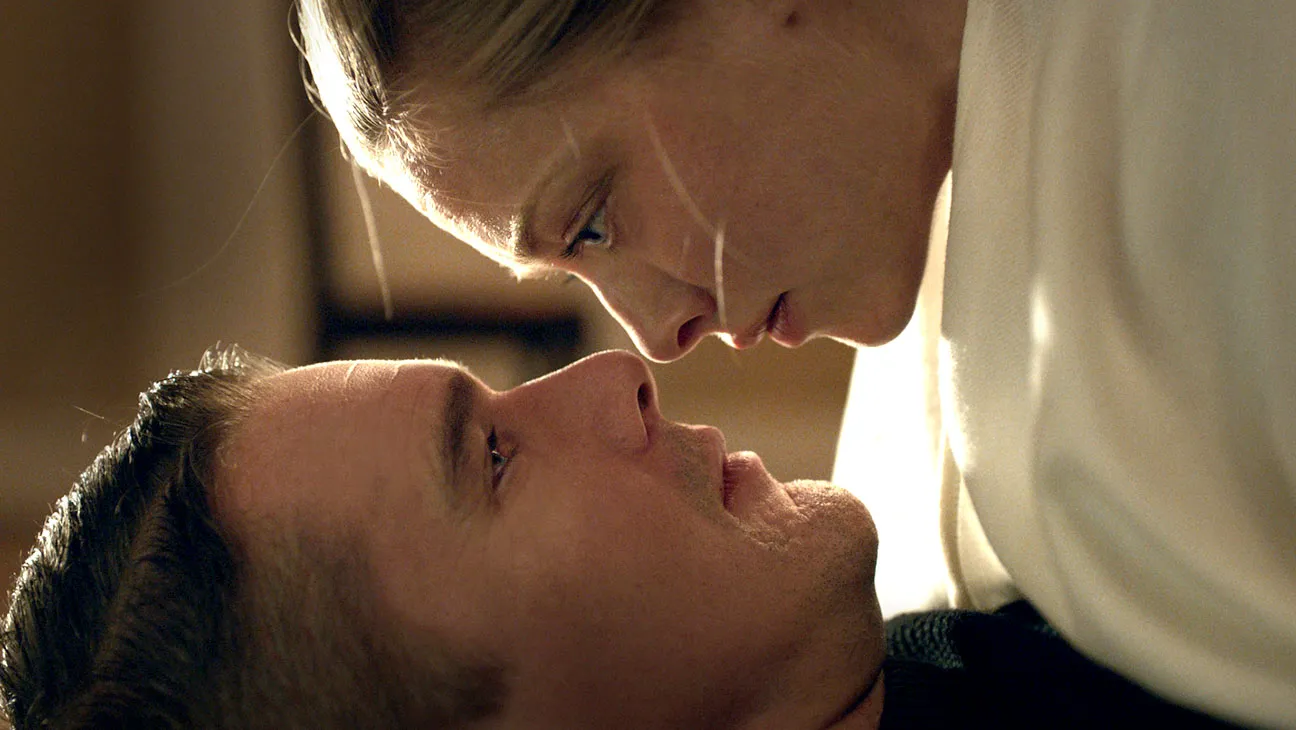

One evening, Mary visits the clergy house, deeply anxious. When Toller asks how he can help, she shares a calming ritual she once practiced with Michael: lying on top of one another, fully clothed, breathing in sync. After a moment of hesitation, they try it. What begins as an act of comfort turns transcendent. Toller has a vision: they’re floating through space, soaring over mountains and forests.

But then the vision darkens—smokestacks, industrial wastelands, ecological destruction creeping in. The dream collapses into a nightmare. The next morning, Toller helps Mary prepare for her trip to Buffalo, where she plans to stay with her sister. She says she wants to attend the Reconsecration, but Toller insists she stay away.

Does Toller go through with his plan at the ceremony?

Alone, Toller begins testing the vest. He even visits Balq Industries wearing it, returning later for a quiet dinner of miso soup and fish. On the eve of the ceremony, Jeffers checks in again, gently suggesting that Toller step away from the event. But Toller refuses—this too, he says, is sacred to him. Just before the ceremony begins, Toller arms the suicide vest and prepares to walk into the church.

But as he watches the attendees arrive, he spots Mary. She came anyway. In a panic, he tears off the vest, wraps himself in barbed wire from the church cemetery, and dons his white clerical alb. Standing alone, he pours a glass of drain cleaner, ready to drink. Then Mary finds him. She interrupts. He turns to her. And without a word, they passionately kiss.

First Reformed (2017) Movie Themes Analyzed:

The Theology of Despair

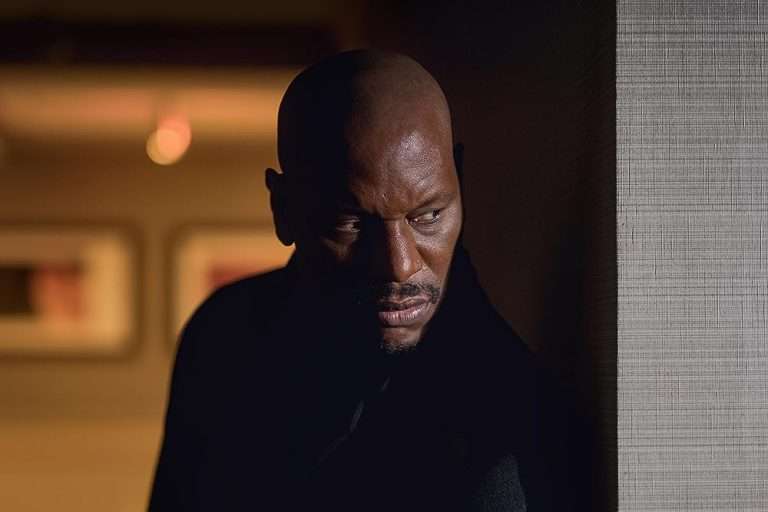

Reverend Ernst Toller learned whatever he could about God’s grace through scripture and the soft cadences of church teachings. But in the cold, austere clergy room he now inhabits—cut off from love, family, and warmth—God speaks only through silence. The ancient First Reformed church, now more of a hollow tourist relic, mirrors this state of spiritual abandonment. This is the heart of despair that Schrader dissects with quiet brutality and Ethan Hawke embodies with raw precision.

The film navigates two theological frameworks of despair. One condemns it as a sin—a turning away from divine purpose. The other views it as a necessary, almost sacred reckoning with existential truth. “First Reformed” charts a descent from the righteous kind of despair—the kind that demands answers from God—to a bleaker, darker place that blurs spiritual crisis with personal collapse.

The diary, doomed from the moment he begins, is less an attempt at healing and more a slow unraveling. Michael’s arrival isn’t a revelation—it’s a catalyst. His grief is environmental, and his dialogue with Toller appears theological at first glance. But once Mary reveals that Michael was an atheist, it becomes clear that this isn’t a divine inquiry. It’s theological nihilism, a quiet rejection of sacred order. Toller doesn’t embrace it, but he doesn’t reject it either. His ink-drenched confessions suggest he’s slipping further into this abyss.

Søren Kierkegaard, in The Sickness Unto Death, claimed that true despair is the disconnection of the self from both God and one’s own being. That’s exactly what happens here. Toller is coming undone and, paradoxically, coming of age, though his growth feels like an undoing. And his act of chronicling it all by hand, not digitally, feels like a self-imposed ritual of suffering. Not to understand himself, but to endure himself.

Faith vs. Corporatism

Capitalism, like any well-oiled religion, has its rituals, its dogmas, and its gods. In “First Reformed,” it even has a Jesus: Edward Balq. Wealth incarnate, he sits at the center of the church’s future, determining not just its funding but its very voice. The reconsecration ceremony doesn’t celebrate a historic sanctuary—it marks its quiet assimilation into corporate theology. When the pomp begins, the film doesn’t care about spectacle. It only cares about Toller’s trembling body, his escalating detachment, his psychic hemorrhaging beneath the surface.

Then there’s Pastor Jeffers, an enigma wrapped in gentle tones. He’s sympathetic, even tender in moments, but always a mouthpiece of the larger machine. Abundant Life, in all its sterile grandeur, doesn’t feel like a church. It feels like a school run by PR consultants. The dynamic between Abundant Life and First Reformed isn’t just hierarchical—it’s parasitic. And Jeffers, for all his empathy, remains complicit. The modern church isn’t a sacred refuge—it’s a corporate outpost. Piety bows to profit. And Schrader, razor-sharp, never lets us forget it.

Masculinity in Crisis

Reverend Toller is the textbook image of a man socialized to be composed, restrained, and stoic—to carry pain in silence and bleed only in metaphors. But “First Reformed” strips him bare. It reveals how masculine identity, especially within religious frameworks, can become a prison of self-denial. Toller does not scream. He does not beg. He writes. Toller drinks. He punishes his body like it’s the only thing he owns. And in that suppression, Schrader shows us the rot.

Masculinity here is not loud or dominating. It’s silent, internalized, and ultimately implosive. Toller’s masculinity doesn’t protect him; it isolates him. The expectations of strength keep him from seeking help. The weight of doctrine keeps him from embracing vulnerability. His descent into radicalism isn’t born out of power—it’s born out of a lifelong fear of appearing weak. The suicide vest becomes the most grotesque symbol of this implosion. Not just a political act but a personal one. A way for a man to finally “act” in a world that’s rendered him spiritually impotent.