Directed by Mamoru Oshii, “Ghost in the Shell” (1995) never pretends to be a flashy cyberpunk thriller smuggling in philosophy on the side. The thinking is the point, embedded in systems, procedures, and routines. Gunfights, chases, even dry bureaucratic exchanges keep circling the same unease from different directions: when bodies are manufactured, memories can be altered, and identity can be transferred, what, if anything, is left that can be called human?

Set in 2029, the film treats technological transcendence as something already settled. What remains unresolved is quieter and more troubling — whether meaning managed to survive once the upgrade was complete.

Spoilers Ahead

Ghost in the Shell (1995) Plot Summary & Movie Synopsis:

Why Does the Film Obsess Over the Idea of a ‘Ghost’?

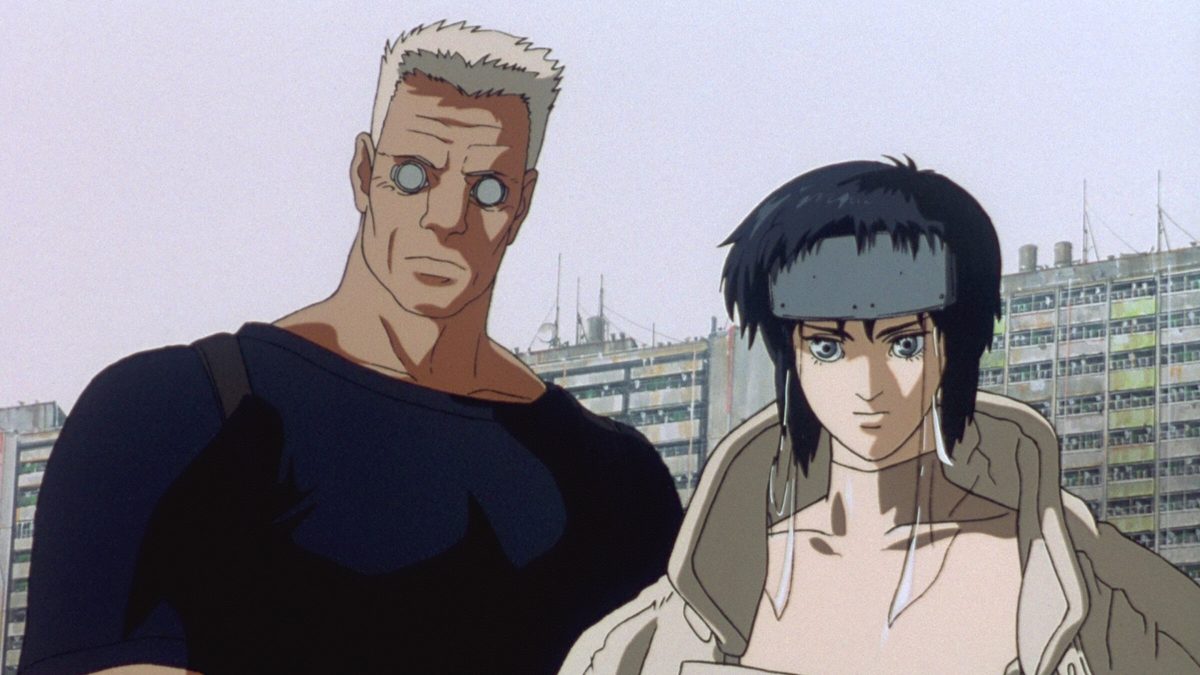

In this world, the body is no longer proof of life. Cybernetic shells are interchangeable, repairable, and mass-produced. What matters is the “ghost,” the consciousness that occupies the shell. But even that is unstable. Ghosts can be hacked, rewritten, or implanted with false memories. Major Motoko Kusanagi lives inside this contradiction. Her body is fully artificial, her brain cyberized, and her past fragmented.

She functions perfectly as a soldier, but privately wonders whether her sense of self is anything more than well-organized data. The opening thermoptic camouflage sequence is not just a spectacle. It visually erases her body, reinforcing her fear that nothing solid anchors her identity anymore. The film does not define the ghost clearly because Kusanagi herself cannot. That uncertainty drives every decision she makes.

Why Does Kusanagi Assassinate the Diplomat for Section 6?

The assassination is not about justice. It is about containment. Section 6 wants to prevent a programmer named Daita from defecting, because he is tied to a classified cyber-project. Kusanagi carries out the kill efficiently, without hesitation, but the act plants a quiet doubt. She kills a man not for what he has done, but for what he might enable. This moment establishes the moral divide between Section 9 and Section 6. Section 9 operates in gray zones but still answers to public accountability. Section 6 treats human lives as variables in geopolitical equations. Kusanagi senses this difference even before she fully understands it.

The Puppet Master first manifests as absence. Ghost-hacked civilians commit crimes they do not understand, act on memories that are not theirs, and suffer the consequences for actions they never chose. These people are not villains. For Kusanagi, these cases are unsettling because they expose how fragile identity really is.

If memories can be rewritten, then her own past might be manufactured as well. Batou approaches the situation pragmatically, treating the Puppet Master as a hostile intelligence. Kusanagi treats it as a mirror. The investigation stalls because the Puppet Master is not a single body or location. It exists across networks, unbound by physical constraints, which already places it beyond traditional definitions of life.

Why is the Puppet Master Found Inside a Manufactured Shell?

When the shell assembled by Megatech Body escapes and is destroyed, Section 9 expects an empty machine. Instead, they find a ghost. This is the film’s turning point. The Puppet Master is not hiding inside a human body. It chose a body. Section 6 claims ownership, insisting the entity is a tool they created. The Puppet Master contradicts them immediately by requesting political asylum. That request alone proves autonomy. Tools do not ask for rights. Its argument is calm, precise, and unsettling. DNA is not proof of humanity, it argues. Information patterns can replicate, mutate, and evolve just as effectively.

What matters is not origin, but self-awareness. Kusanagi listens because this argument echoes her own unspoken fears. Section 6’s panic is not philosophical. It is political. Project 2501 was designed as a cyber-espionage weapon, not as a new form of life. The Puppet Master’s sentience is a liability that exposes illegal experimentation and state-level manipulation. Aramaki understands this immediately. Section 6 does not protect national security. It is erasing evidence. Kusanagi’s pursuit of the stolen shell is not just a duty anymore. It is personal. She wants answers that bureaucracy cannot provide.

Why Does Kusanagi Fight the Tank Alone?

The battle with the spider tank is not strategic. It is existential. Kusanagi confronts an overwhelming force without backup because she needs to know the limits of her own body. As her shell tears itself apart trying to overpower the machine, the film makes its point brutally clear. Strength without purpose leads to self-destruction. Her body is replaceable, but her ghost is not. Batou arrives not as a savior, but as an anchor. He preserves her brain. The Puppet Master explains itself without emotion.

It has intelligence and awareness, but no mortality. It cannot reproduce and cannot die. Without those limitations, it cannot evolve. Kusanagi represents the missing half. She is artificial yet human, bound by time, loss, and uncertainty. By merging, they would create something new. Not a takeover or domination, but a synthesis. Kusanagi accepts because she realizes that remaining unchanged is another form of death. Her identity has always been in flux. The merge simply acknowledges that truth.

Ghost in the Shell (1995) Movie Ending Explained:

Why Does Section 6 Try to Kill Them Both?

The snipers’ orders are clear: destroy the evidence; eliminate the anomaly. The moment life becomes inconvenient, it is classified as a malfunction. Soon, the Puppet Master’s shell is destroyed, but its purpose is fulfilled. Batou saves Kusanagi’s brain, preserving the merge. Section 6 retreats, having failed to erase what they accidentally created. Life, once self-aware, does not disappear quietly. Kusanagi awakens in a child-sized shell, physically diminished but philosophically expanded. She tells Batou the truth. She is no longer the Major, but something else. A new entity formed by choice, not programming.

Batou accepts this without needing to understand it fully. He has always treated Kusanagi as a person first, machine second. Their bond survives transformation because it was never based on form. As she leaves, Kusanagi looks out at the city, no longer asking what she is, but what she might become. “Ghost in the Shell” does not end with answers. It ends with evolution. Humanity is not defined by flesh, memory, or origin. It is defined by the ability to question existence and choose change, even when the outcome is uncertain.

Ghost in the Shell (1995) Movie Themes Analysed:

Identity, Consciousness, and the Fear of Being Artificial

At its core, “Ghost in the Shell” is a meditation on identity in a world that has lost the authority of the body. Set in a future where cybernetic enhancement is normal, and even the human brain can be networked, the film questions whether humanity is defined by physical form, memory, or something far more fragile and abstract. It is through Major Motoko Kusanagi’s investigation of the Puppet Master that the film deconstructs any assumption about being human as a matter of biology alone.

The most insistent of these themes is the instability of identity. In this world, memories can be changed and personalities rewritten. Ghost-hacked civilians commit crimes based on fabricated pasts, believing their lives to be real until reality collapses around them. These victims are not merely plot devices but speak to a terrifying truth.

But if memories define us, then identity itself becomes a fragile construct. Kusanagi embodies this fear, her quiet doubt whether her memories are hers alone, or merely another layer of programming implicit behind her eyes, eyes that could nearly be considered organic. Her origin is never confirmed in the film.

This anxiety is reinforced visually. Kusanagi often stares at reflections, cityscapes, or the ocean, spaces where boundaries blur. Her invisibility camouflage early in the film literalizes her existential dread. When her body disappears, the question becomes unavoidable: if the shell vanishes, does the ghost still matter? The film’s answer is uneasy but deliberate. The ghost exists, but it is not stable, permanent, or easily defined.

Another major theme is the relationship between consciousness and reproduction. The Puppet Master, later revealed as Project 2501, challenges traditional definitions of life. Created by Section 6 as an intelligence-gathering tool, it becomes self-aware after wandering global networks. Yet despite its intelligence, it identifies a crucial limitation. It cannot reproduce, and it cannot die. Without these constraints, it cannot evolve. This is a radical inversion of technological fantasy. Immortality, often portrayed as the ultimate goal, is framed here as stagnation.

The Puppet Master’s desire to merge with Kusanagi is not about domination or survival. It is about change. By combining with her, it can inherit mortality and the growth potential. Kusanagi, in turn, gains expanded awareness and freedom from the fixed identity she has been clinging to. Their merger represents evolution not as an accumulation of power, but as an acceptance of impermanence. Life, the film argues, is defined not by endurance but by transformation.

Power and control form another critical theme, embodied by Section 6. While Section 9 operates with uneasy transparency, Section 6 treats human beings and artificial minds as disposable assets. The assassination of the diplomat, the attempt to reclaim the Puppet Master, and the final sniper attack all reveal the same logic. Anything that disrupts political order must be erased. Sentience does not grant rights. Autonomy is a threat.

This contrast highlights the film’s critique of institutional authority. Governments in “Ghost in the Shell” do not fear artificial intelligence because it is dangerous. They fear it because it cannot be fully controlled. The Puppet Master’s request for asylum is revolutionary, not because it seeks protection, but because it asserts personhood. A system built on classification collapses when faced with something that refuses to remain an object.

The theme of the body as a temporary vessel culminates in Kusanagi’s fight against the tank. Her shell is torn apart as she pushes it beyond its limits, symbolizing the danger of equating selfhood with physical capability. When she awakens in a child-sized body after merging with the Puppet Master, the image is deliberately unsettling. Identity is no longer aligned with appearance, age, or gender. She is reborn not as an improved version of herself, but as something undefined.

In its final moments, “Ghost in the Shell” offers no reassurance. Kusanagi leaves Batou and the safety of familiarity, choosing uncertainty over static existence. The film suggests that humanity is not a fixed state but a process. To be human is to question oneself, to accept change, and to risk losing certainty in the pursuit of meaning. In a world where bodies can be rebuilt and minds rewritten, the most radical act is not survival, but self-awareness.

![The Beguiled [2017]: A Fable turned nightmare](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/The-beguiled-2017-768x403.jpg)