There’s a deep sadness at the heart of Atiye Zare Arandi’s documentary, Grand Me. Arandi’s eight-year-old niece is the focal center, a curious, lively presence who is not only sad and disappointed in her parents but also unhesitant in pulling back on her bitter anger at them for repeatedly letting her down. Melina isn’t coy or reserved in making her displeasure be heard loudly and clearly. It is a tragedy that neither of her estranged parents is particularly willing to properly listen to her nor adept in gauging the root of her anger. Although the father registers his presence in the film only on the phone calls, both he and Melina’s mother, Atefeh, seem more comfortable retreating and having someone else assume her responsibility.

The film especially foregrounds Melina’s relationship with her mother. In the car, the former can barely repress her rage and resentment of the latter for all the distance that has crept up between them. Often shaken by her daughter’s attacks, Atefeh confesses feeling so judged by her she isn’t quite sure how she can earn Melina’s faith and intimacy. Since Atefeh has remarried someone who has his own adult son, Melina is furthermore incensed by her mother, who is devoting little time to her. While Atefeh questions her daughter on whether she thinks she has no right to lead a life beyond the maternal framework of duty, Melina hits back, charging her mother as to why she had to marry to get the right.

It is one of that bullet-like precocious wisdom of kids that can cut through any fog of wrongful socialization into the supposed roles laid down for girls and women. In a scene, we witness one of these pernicious lessons-giving by old authorities to young girls, instructing them to stick to the hijab and avoid divine and social disgrace. The advised set of rules imposed upon women from a young age is outrageous.

But as Melina’s stinging protests in her conversations with her mother attests, these girls know how to push back against the baggage of such enforced dressing and behavior. They are all capable of waging their private rebellions, defying any norm through the lens of their wiser intelligence. Melina is so perceptive that she can be rude and awful in the harsh assessments of her parents, who seem to have abandoned her. However, the empathetic position Arandi is able to generate ensures Melina’s brutal candor never makes us stray from the pathos in her emotional predicament.

Melina lives with her grandparents in Isfahan. It is an adoring ecosystem where she feels nurtured and genuinely cared for, but she longs to live with her mother in Tehran. When her mother suggests a vacation to Turkey, which Melina can take, the latter pleads with her father to get her a passport. The father, however, keeps dodging the proposal as he is averse to her living with her mother. While Melina vociferously criticizes her mother, she is more reserved in voicing the discomfort she experiences when she stays at her father’s place. Although the daughter shows a keen wariness of going by norms, her differing attitudes toward her parents present a subtle critique of overtly gendered expectations. In spite of her abject disillusionment with both of them, Melina comes across as doubly unsparing in interactions with her mother.

Despite her grandparents trying to shield them from the frequent heartbreak she gets from her parents, Melina chooses to be confrontational, provoking them into paying her the attention she deserves. The film closely inclines us to her appeal. Even if she is surrounded by her fiercely protective, affectionate grandparents, her loneliness and gloom seep into every pore of the film and the viewer’s being.

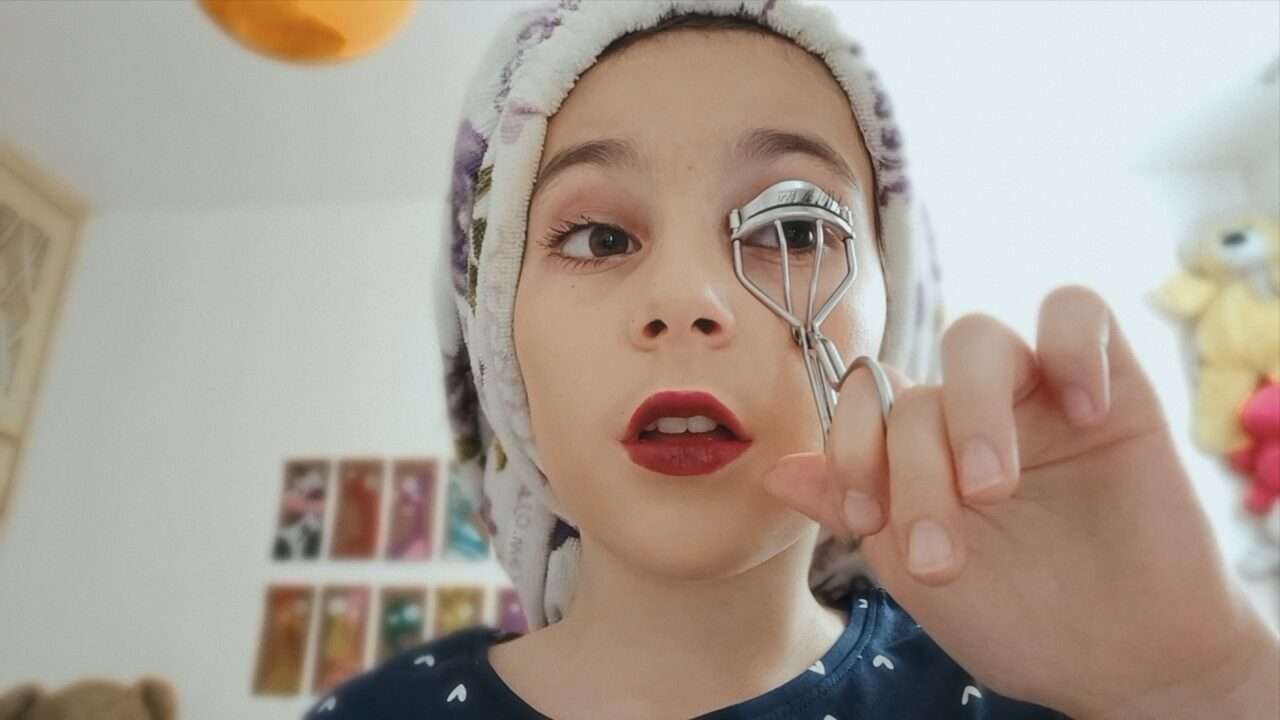

She tries to spend time by herself, filming herself putting on makeup. She plays with her grandparents, yet her thoughts ultimately keep returning to her parents, who also, as she admits before Atefeh, annoy her. There are these shattering moments when she desperately clutches onto her mother when the latter prepares to leave after briefly dropping by. In the tussle between the daughter anxiously holding on to her mother and the weary latter struggling to break herself loose lies the fragile, tender heart of this film.

![The Disaster Artist [2017]: Filling the Hollow](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/the-disaster-artist-768x432.jpg)

![Goddess of the Fireflies [2020] Review – A story of freedom](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Goddess-of-the-Fireflies-highonfilms-768x398.jpg)