In the wake of the departure of British power, the fledgling nation-state, India, began the process of nation-building with a certain nationalist zeal. However, the formation of the nation-state also came at a cost- a cost which had to be paid by cleaving British India into India and Pakistan, with the ensuing bloodbath and the large-scale deracination and displacement of lives on both sides of the border. Perhaps the most recognizable consistent thread that unites such films as “Shree 420” and “Mother India” is their cinematic embodiment of the newborn nation and its unwavering faith in Nehruvian socialism.

While “Mother India” embodies and idealizes—as Brigitte Schulze has noted—the contribution of the rural population to “the foundational myth of Nehruvian socialism,” it is “Shree 420” that evokes the emerging cityscape and captures a migrant’s attraction to, and eventual disillusionment with, urban modernity and capitalism in the years following independence, all while remaining firmly within the realm of melodrama.

It is pertinent to mention here that it is not only “Shree 420” that explores the emergent urban space in the formative years of India. In fact, in the formative period, parallel to the release of these films, there can be traced a development of a patch, formed by a cluster of films which consistently transgressed the circumference of melodrama and dealt with the subject of crime pulsating in the seedy underbelly of the burgeoning cities —especially Bombay but also occasionally other cities like Calcutta— in the newly formed nation-state.

These films, through their narrative motivation and their expressionistic visual style, are remarkable not simply for their nod to Hollywood film noir but also their conflation of the ‘noirish’ world of crime with comic interjections and romantic interludes, and thereby transmogrifying American noir into a new variant- Bombay noir.

David Satterthwaite’s account on the scale of urban change globally during the period of 1950-2000 suggests that the dissolution of European colonial powers in most nations of Africa and Asia led to the changing dynamics of the urban spaces of those nations. This observation is underpinned by the fact that the cities, especially Bombay, Calcutta, and Lahore, witnessed a large influx of population in the years following the Partition.

The rebuilding of these cities, then, was effectuated from the point where the colonizers left. Hence, the mood of despair, nihilism, and post-war disillusionment that ran as an undercurrent through the Hollywood film noir is seemingly absent from Bombay noir. The spirit of Bombay noir, in stark contrast, lies in the interplay between the apprehension and excitement resulting from the colossal expansion the city had to experience to accommodate the motley of identities.

In this study, we focus on two films from the Bombay noir cycle- “Aar Paar” (Guru Dutt, 1954) and “12 O’Clock” (Pramod Chakravorty, 1958), both of which cast Guru Dutt as the hero. “Aar Paar” opens in a prison, where we meet Kalu Birju (played by Guru Dutt) for the first time. This singularly makes it clear that the hero is an outlaw. However, Kalu’s innocent fear of getting caught for an innocuous act of smoking bidi in the toilet and the jailor’s declaration, to Kalu’s surprise, that his honesty, hardwork, and good conduct has fetched him mercy on the last two pending months of his punishment construct him as an outlaw who has perhaps slipped into illegality by accident, both literally and metaphorically, with no other ulterior motivation.

This is a marked difference from the Hollywood noir heroes, who are not so much naive, a trait of their Hindi counterparts, as they are cynical and morally ambiguous. It is just before Kalu leaves the jail that the noir motivation is set in motion with Qaidi No. 114 surreptitiously passing over information concerning Captain, whom he would find at South Street Hotel, and a recondite message meant for Captain.

Explore More: City As Character: 10 Distinct Cities in Cinema

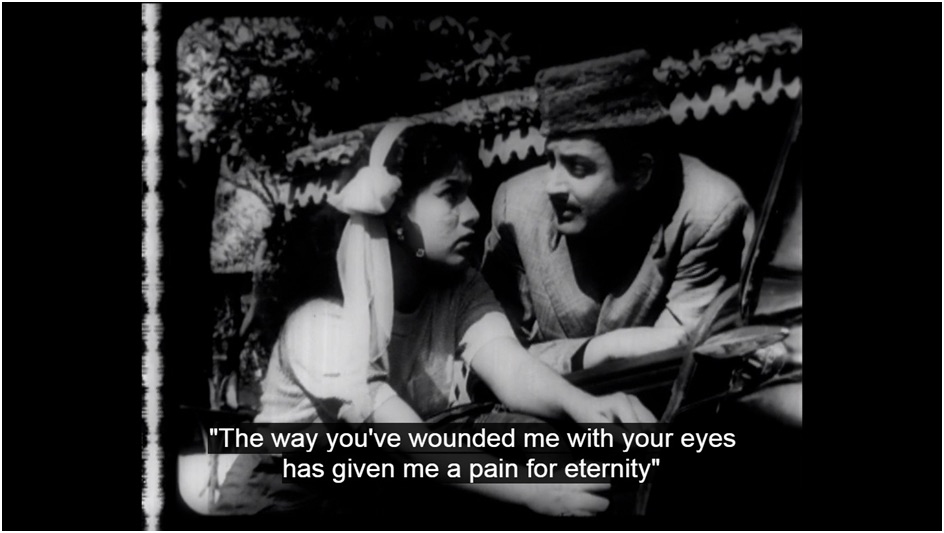

When Kalu trudges along in a street of Bombay, he trips over a pair of legs protruding from underneath a stationary car. Mistaking the pair of legs for a man’s, he pulls them, and it is revealed to be a woman. After a brief altercation between the two, the first song sequence of the film begins. The song, “Kabhi aar kabhi paar laga teer-e-nazar” (“Sometimes here, sometimes there/these eyes are like arrows”) begins with a dance of street children and picturized as being sung by a woman working in a construction site (Dutt, 1954, 00:06:03-00:11:26). However, while the street children appear to share the same continuous space and time as Kalu and Nikki, the woman driver, there is little evidence that the woman worker is in close proximity to them.

The choice of the inclusion of the woman worker, then, can be explained as an oblique but also visual commentary on the rapid urbanization of Bombay in the post-Independence years. The euphoria of love at first glance is paralleled by the euphoria of a city in the making. With Kalu’s arrival at South Street Hotel, the film introduces the femme fatale—the nameless moll of Captain—played by Shakila.

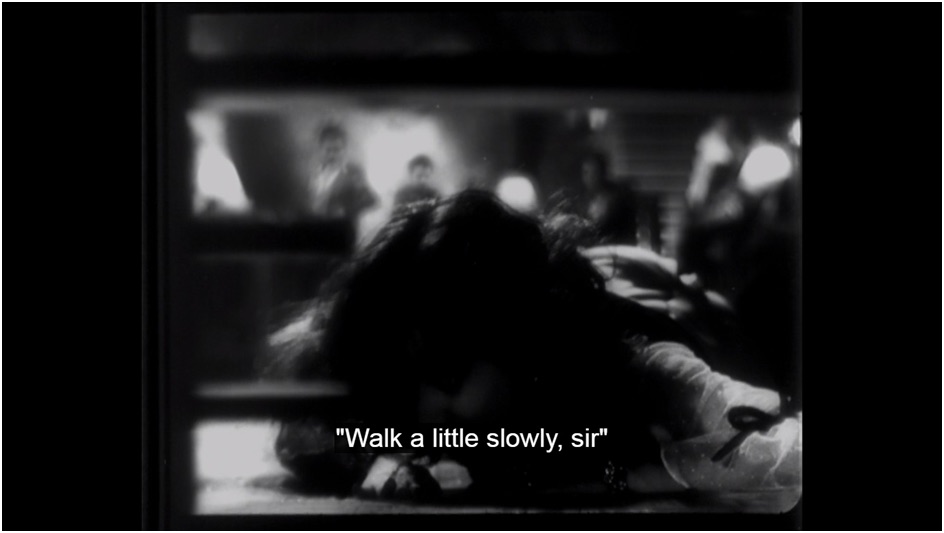

The euphoric atmosphere of “Kabhi Aar Kabhi Paar” is supplanted by the amorous forebodings of the moll, through her song, “Babuji dheere chalna/Pyaar mein zara sambhalna” (“Walk a little slowly, sir/ Watch your steps when you fall in love”) which insinuates a strong likeness between treading the path of love and the deceptive, dark alleys of the city (Dutt, 1954, 00:19:48-00:23:20). The suggestion of the emergent urbanity and its accompanying moral decadence is not restricted to the song lyrics; it is also reflected visually through the mise-en-scène and the lighting of the interiors of the dubious hotel.

The low-key noir lighting in the hallway, along with the woman’s refusal to divulge details, obscures various areas of the frame and the dancer’s face—and, by extension, her motivations and true nature. The surrounding shadows, darkness, and even smoke carry overtones of the unexplainable and the unknown.

Even in light comic and romantic sequences, the noir-style lighting and mise-en-scène evince an unromantic atmosphere- one of uncertainty and precariousness. One cannot help but wonder about the creative motivation of V.K. Murthy, the cinematographer of the film, who also plays the role of Jailor Saxena, behind filming this sequence (00:28:38-00:32:30) with such low-key lighting. With Kalu outside and Nikki (played by Shyama) inside-visible only through the small, grilled window of her room, this frame (Fig. 7) is an implication of the distance between them in relation to their position on the social ladder. It can also be read as a remark on the proliferation of migrant workers in the city and their dingy workplace environment.

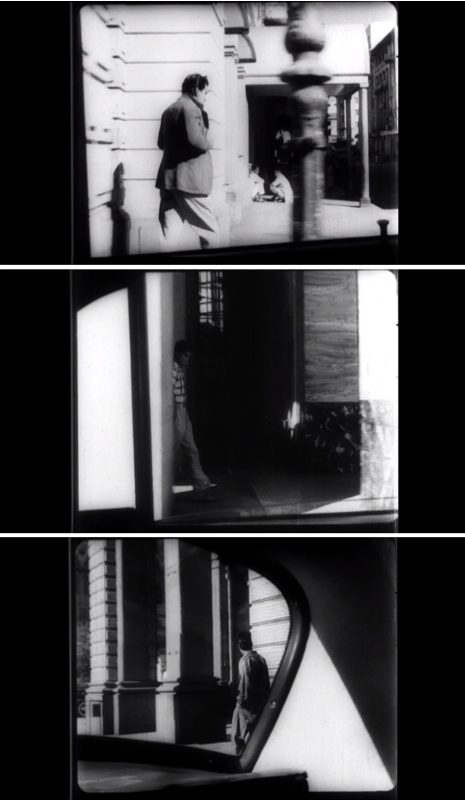

The light French clair camera is put to use yet again in “Aar Paar” as is evident in the sequence of the rehearsal of the bank robbery carried out by Captain and his companions(00:59:15-1:01:43). The camera in observing —as a flâneur from within the taxi —the characters pacing up and down the streets of the city also seems to observe the relics of the colonial past in the architecture of South Bombay (Fig. 8.- Fig. 10.). Ranjani Mazumdar notes that filming the city from the point of view of the taxi suffused the otherwise noir style with a ‘wanderlust aesthetic’.

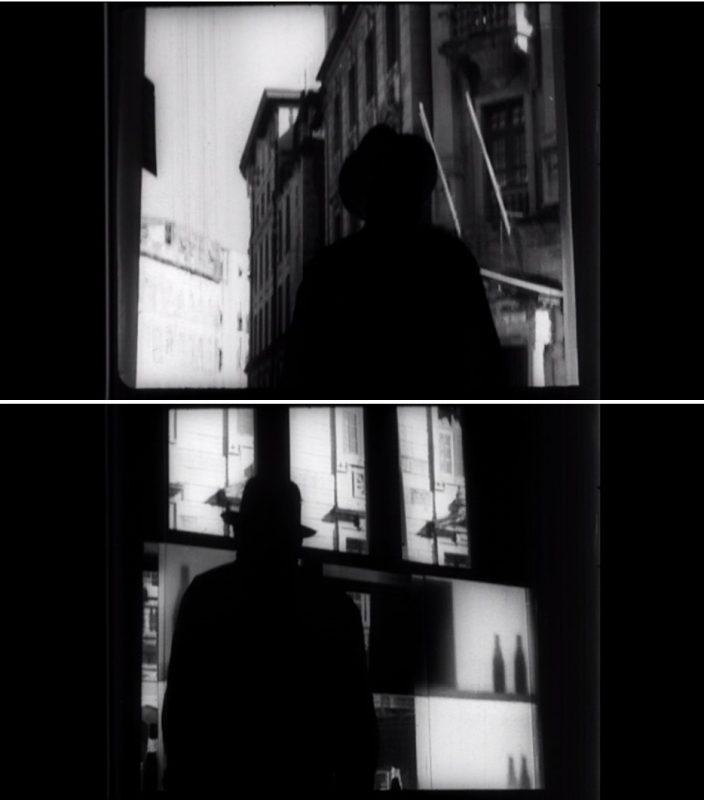

The dark silhouetted figure of the Captain against the background of the building of the bank in broad daylight creates an opposition of light and dark, which evinces a sense of threatening aura looming over the city (Fig. 11 and Fig. 12). The low angular shots used in this outdoor sequence intensify the tension of the narrative.

That Bombay was a melting point of diverse social groups and cultures is made apparent through the dialogues of the film, written by Abrar Alvi. This also puts into perspective the immense transformation of the city to make room for every diverse character.

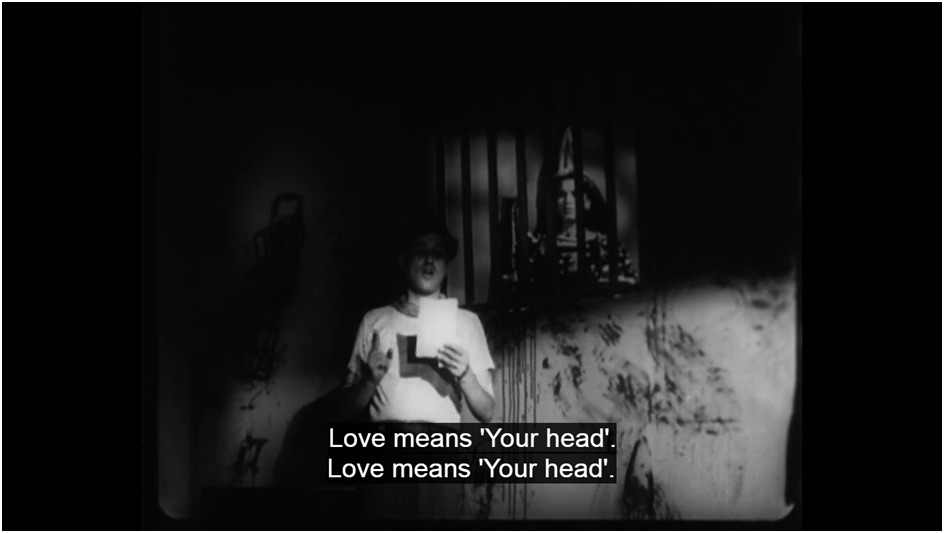

In yet another Guru Dutt-V.K. Murthy collaboration- with Dutt playing only the hero this time-”12 O’ Clock” employs the low-key lighting, and we see the faces of Guru Dutt and Waheeda Rehman constantly enshrouded by an ominous darkness. This darkness, even in romantic situations like “Aar Paar,” conveys unknown tensions and anxieties in the changing face of the city— tensions that have crept into the private lives of the people. When Bani, played by Waheeda Rehman, arrives at the doorstep of her uncle’s house, she is seen standing in the dark with no corners of her face rendered visible.

The cycle of noir films produced in the decade of the fifties, thus, makes glancing commentary on the emergent urbanity through such commonplace noir tropes as gambling dens, femme fatales, all indulging in a world of crime against the backdrop of the city. The city being central to the narrative of these films is testified by the fact that most of the films made during this period had names associated with the urban way of life, for example, “12 O’Clock” and “Taxi Driver” (Chetan Anand, 1954).

The cycle—most notably initiated by Guru Dutt and the Anand Brothers (Dev, Chetan, and Vijay)—along with collaborators like cinematographer V.K. Murthy and even Johnny Walker, who often played the jester in these films, brought together diverse genres such as romance and comedy under a distinctly noir aesthetic. This conflation becomes a subtle articulation of the angst and exhilaration of the post-Independence Bombay, which became a vast, complex field of both optimism resulting from the newfound independence and paranoia of the city going astray due to the rising modernity.