The film’s title caught my attention long before I dived into this 83 minutes-long magical-realist experience. It is borrowed from one of T.S. Eliot’s most famous and oft-quoted poems, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Was the excerpt I had read about the film misguiding since it never mentioned a balding, aging man but a spritely, aspiring, young photographer? A comedy-drama directed by Patricia Rozema, popularly associated with the emergence of the Toronto New Wave in cinema during the 1980s, I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing opened at the Cannes Film Festival in 1987 and received a six-minute standing ovation after its conclusion from the audience members. It is simple and profound to equal extents; measuring out the magical-realist experiences around art, love, and everyday life in coffee spoons.

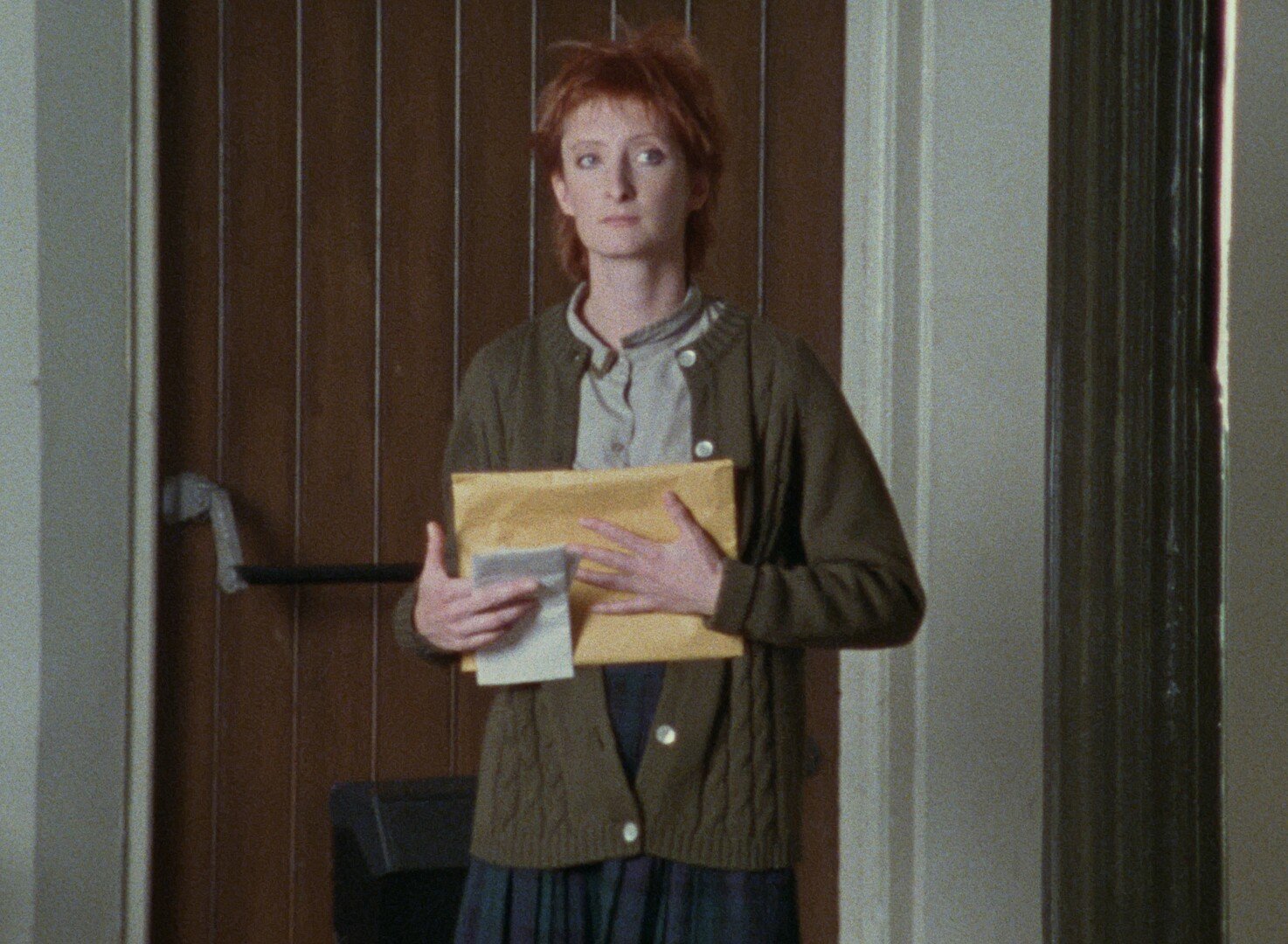

Polly Vanderseva, played by Sheila McCarthy, is a young redhead woman who best describes herself as a “gal on the go”. She fleetingly takes up one job after another, from accounting firms to a toothpaste factory, until she finds herself the role of a temporary assistant position with the curator, Gabrielle, played by Paule Baillargeon. She is too clumsy to work on a typewriter; when she is out on the street taking pictures, her passion comes alive. Polly becomes fascinated with Gabrielle, her private life, and her work, so much that she summons the courage to stand up for Gabrielle when her work is criticized by a male peer. However, the closing distance between her life and Gabrielle’s makes her encounter uncomfortable truths. Can Polly, a person who drinks milk and eats crackers for dinner, stand this discomfort, or does she drown under the weight of these complex human consciousnesses? The film leaves you enchanted, smiling, and wishing it weren’t so damn short and poetic.

Related to I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing – Feast [2021] ‘MUBI’ Review: An insightful yet frustrating Feature

The theme of queer identity runs distinctly through the narrative. Before we proceed to discuss the same, it is essential to keep in mind that we are talking about the Canadian notions of queerness – a progressive state which had already granted queer people equal rights, protection, and benefits under the Canadian constitution in the early 1980s. Thereafter, the film never problematizes the idea of gender and sexuality. In a beautiful shot, when Polly is admiring herself in the glass outside a building in a public place after she has concluded that she might be in love with Gabrielle, “not kissing and all that stuff” as she confesses, the audience sees her posing, broken reflection.

The fragmentation of a flawed preconceived identity is brought out but not doted upon in the course of the film. In one of her many mental escapades, she seems to be full of insight into how gender is irrelevant in matters of the heart. To that extent, she goes on to talk about Freud’s idea of “polymorphous perversity” and counter the same. While it may sound didactic, considering Polly comes off as a shy, awkward girl, her profound thoughts make sense only in her little escapes into black-and-white fantasy. In another scene, when she questions Gabrielle’s lover, Mary, played by Ann-Marie Macdonald, about the nature of their love, neither Polly nor the audience is shocked by the knowledge of romantic love between the two women. What is more interesting throughout the film is the female gaze, automatically making it stand out in the 1980s for not sexualizing women beyond the agency they command in their roles.

I must make a small note about the background score in this film which actually attempts to replicate the voices of the mermaids singing, albeit successfully. It is a commendable little touch to the narrative. Further, Polly performs sections from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony in one of the scenes, and those few scenes will always be remarkable for bringing together Polly’s inner and outer selves into one masterful conductor, a person she can never wholly become.

Also, Read – 5 to 7 [2014] Review: Cinq à Sept with The Mermaid

Sheila McCarthy steals the show as Polly. She has a face that conveys so little it ends up speaking volumes, especially in the scene when Polly first chances upon Gabrielle’s work of art. Her face undergoes visceral changes in expressions until she utters the words ‘nice’ as an adjective to describe it. She slips in and out of her head, and the audience’s, with the calmness of the sea breeze.

However, it is a richly conceptualized character. If you really end up reading the above-mentioned poem by Eliot, which I strongly recommend you do for being able to fathom Polly’s character arc and some subtle references in the screenplay, you’ll realize that Polly is quite opposite to Prufrock in age; yet, they are so similar in their visions, revisions, and indecisions. Her growing disenchantment with Gabrielle (whose arms is braceleted, white, and bare in one of the scenes) recalls to mind the lines, “In a minute there is time/ For decisions and revisions which a minute will reverse”. Last, but not least, I choose to remember Polly in her loose, white flannel shirt and white shoes, another Prufrockian resemblance.

The film probes questions around authenticity and art. It has masterfully selected to lead the audience into the complexly manifold world of artists and art – a world quite incomprehensible for “completely simple-minded” people like Polly. However, what ties it all together is the use of a magical-realist element right at the end. Polly, like Prufrock, knows that the mermaid voices won’t sing to her, but is she willing to indulge herself anyway? The film, I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing, won accolades across 30+ film festivals back in the day. It is like a little fairy-tale brought to life, resting upon (in Rozema’s own words) a ‘distinctly feminist’ foundation.

![Colossal [2017]: Sundance Film Festival Review](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/colossal-2-768x384.jpg)