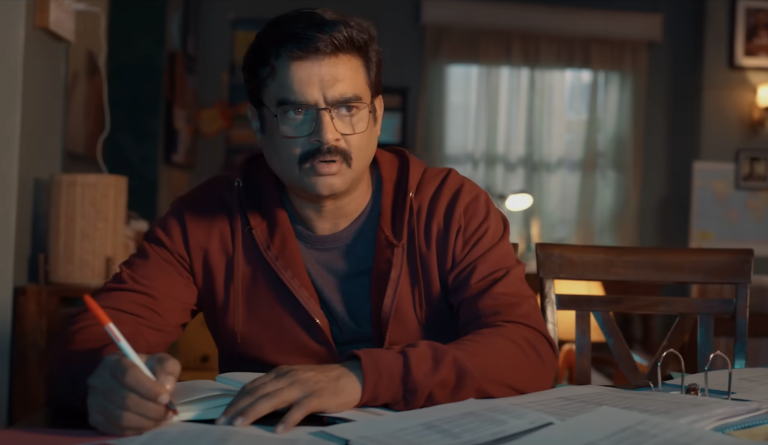

J Stevens’ “Really Happy Someday” is a deeply moving, emotionally nuanced reckoning with transition. Breton Lalama plays a musical theatre performer who has to contend with and accept the churn of transformation, everything that comes with the T-shot. We journey with him as he grows into confidence and peace in his shifting voice, while Stevens’ gaze remains graceful and quietly understanding at every step of the way.

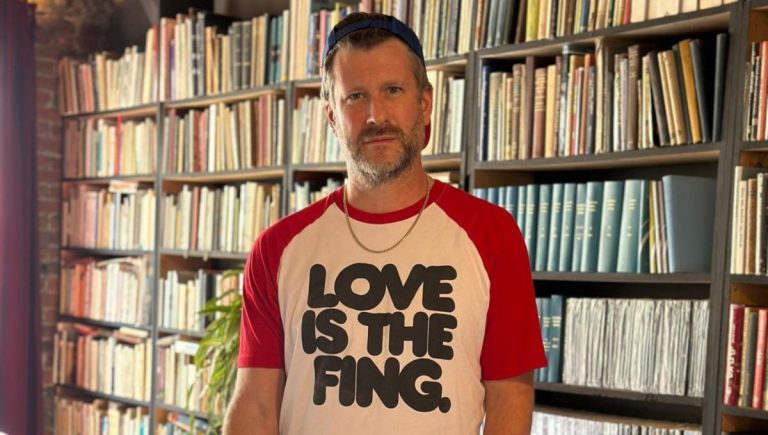

Ahead of the film’s international premiere at BFI Flare 2025, HighOnFilms’ Debanjan Dhar sat down with J to discuss its sudden inception, creating safe spaces for gender-diverse storytellers and more.

Debanjan: The film feels so intimately observed it almost feels like docu-fiction. You shot it over the course of a year. Tell me about the first draft you and Breton wrote together, and how his journey with his voice, his body fused into it, what beats of the narrative you had more or less in place at the start and where you wished to keep it open…

J Stevens: We outlined the script from the start so we knew where we wanted to start and finish. As we’d go to film the next portion, we’d script it out. We did that to stay open to changes, not just in Breton’s voice but to filmmaking. We had an idea of the arc. There was a version of the script where the middle was a bit easier. We thought his voice would get better in a couple of months but there was a moment when it got worse instead and he was frustrated. We shifted stuff around.

Debanjan: You also said somewhere that if there were situations you found too close, you removed them. Can you talk about establishing this separation, working at this along with Breton? Any instances?

J Stevens: Z is a fictional character. I understand the instinct to think they are very similar. There are overlaps. It was important for me to protect Breton since the role demanded such vulnerability. We were drawing inspiration from things that have happened in both of our lives, but also distinctly changed it. Life can be boring so we had to raise the stakes to make the film more interesting.

Debanjan: A chance encounter on the street sparked the film…

J Stevens: Yeah, we followed each other on social media for a while. One day, we crossed the street while going to work. I instantly felt drawn to Breton. He had such a sparkly, magnetic force. That day happened to be his one-year testosterone anniversary. He’d posted a tonne of ask-me-anything videos on Instagram about grappling with vocal transition since he is a performer. I’d been writing a different version of the film and thought what he was saying was so nuanced. So I proposed writing the film together with him.

Debanjan: Was he very open as a co-creator right from the start?

J Stevens: Absolutely. We saw and recognized in each other a safe space for exploring what we wanted to say. I felt so grateful for Breton’s openness both as a performer and writer. We were also intentional. We had a small crew where almost everyone was queer if not gender diverse. So, the performers could feel seen, safe, and cared for, so there was no discomfort or hesitation during the difficult, intimate, vulnerable moments.

Debanjan: Some of my favorite scenes in the film are between Z and his coach, Shelly. There’s such warmth and reassurance in those, as she gently but insistently nudges Z to lean into and embrace the difference. Talk to me about weaving those conversations in; Ali is also Breton’s real-life coach.

J Stevens: Yes! Ali Garrison is Breton’s vocal instructor. Breton suggested Ali could do it. They have such good chemistry; I leaned into it all the more. The space that they are in is her studio where they do all the vocal lessons. The synergy in those scenes comes from the history they share, even though each of them is scripted.

Debanjan: Tell me about getting the rights for Favourite Places. Did you have any other backup?

J Stevens: I wrote a very impassioned letter to Warner Chappell, the music group who owns the rights, about why the song was so important for the film. Breton loves the song. It’s all about searching, dreaming of a place but not quite being able to get there. It was the perfect metaphor for what was happening to Z. Adam Gwon, the composer, who wrote back right away. He attended the TIFF premiere and has been an incredible champion for the film.

Debanjan: I’ve to ask you about Spindle Films, the mentorship you facilitate, building a community of gender diverse creators. I know it’s just been a year but tell me about something that’s been particularly joyful to witness…

J Stevens: Spindle Films was born as a mixture of two things. It was to start the process of making this film and how beautiful and safe the set can be, and to get into Union Television as a director. I had a lot of crew members who came up to me and told me I was the first above-the-line trans person they ever worked with. Naturally, I hated that. I wish there were more folks around who get this opportunity. So Breton and I founded Spindle Films. It’s beautiful to form a community especially now when the news is full of daily attacks on trans and queer people.

Debanjan: I want to take a couple of recommendations. Anything you watched recently that you’d like our readers to check out?

J Stevens: I’ve to say Luis De Filippis. She made the incredible Something You Said Last Night. I saw it at TIFF while I was writing this film and was deeply inspired by her storytelling and the care with which she moved through her film. She is also one of our mentors at Spindle Films.

Debanjan: Finally tell me what you’re looking forward to at BFI Flare. The film has been at TIFF. Are you at all nervous for the screening?

J Stevens: Yeah, it’s our international premiere. I’ve had work play at international festivals but this would be my first in-person appearance. It’s always exciting and nerve-wracking. I always say I like the process of making work more than showing it. My comfort zone is on set. I’m nervous during screenings. I’m constantly surprised and delighted by the response, being in a theatre and feeling the effect it’s been having on people. They are a good reminder of why art is important and why putting trans people’s humanity on screen is vital. It gives me the energy to keep doing it.