Where would you go for something you love? What limits would you cross? What morals would you break? Would you give up your fun for it? Your youth? And your ego? More than that, would you give up your life?

“From here on out, life will only be volcanoes, volcanoes, volcanoes,” says Maurice Krafft to his wife and equally wild Katia Krafft (pioneering French volcanologists). Maybe a little less, for she didn’t want to ride a river of lava and wasn’t boating on a lake of sulphuric acid, unlike Maurice. Their love was finally complete and official.

They were now married, not only to each other but also to volcanoes. Two movies, countless photos, and hours of footage, yet we actually don’t know how they met or how they chose to be volcanologists, heck, I can barely say it. Some blame a cafe, some hold the bench responsible, but as director Sara Dosa mentioned, it was probably sheer luck, destiny if you will.

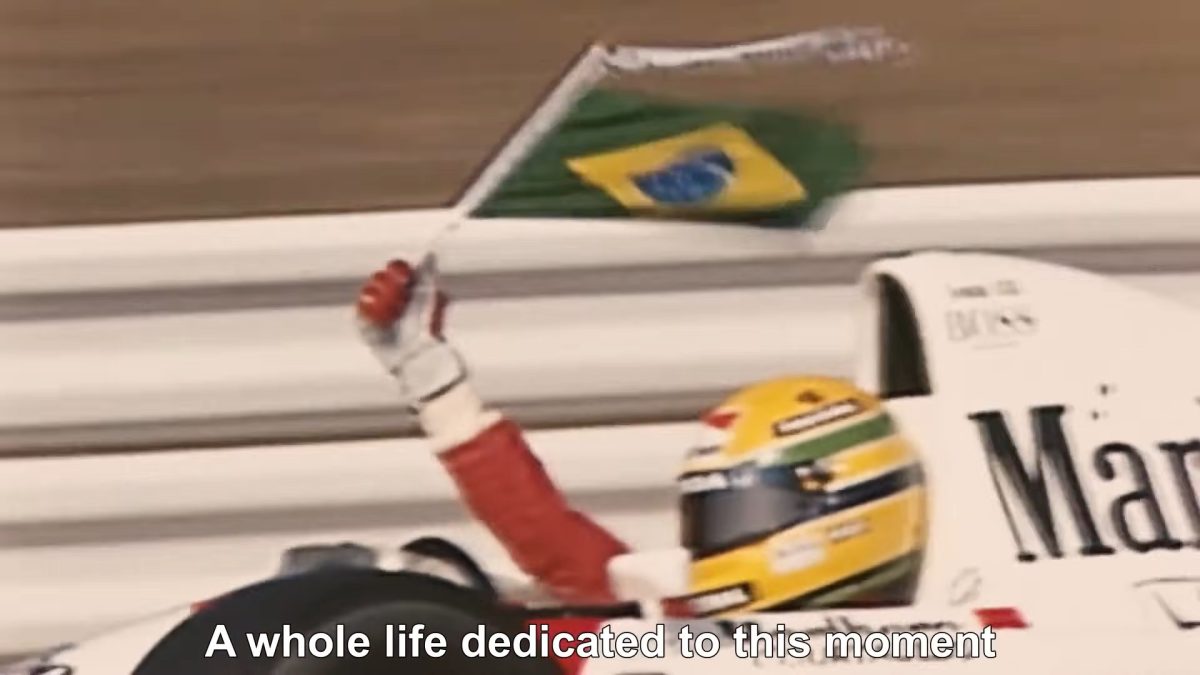

But that’s the thing with passions, it all looks like destiny in hindsight. We don’t know what they were doing before they had their rationed camera film, or how much effort they put into travelling the world. Brazilian F1 racer Ayrton Senna would be called a “prodigy” with the power of hindsight, that he was destined to dominate the drome. Again, we don’t know how many hours Ayrton practiced or how many bones he broke before becoming Senna. After all, the word “passion” comes from the Latin word “passio,” meaning “suffering”. As I mentioned, passion is romantic only in hindsight, when the fog of commitment clears and the sun of success shines. Practice is not televised, panache is.

Young Senna was like a go-kart – running wild, far away from eyeballs. That is, until he became the center of gravity at McLaren and the focus of broadcast at races. After his death, he was turned into the “Senna” of Asif Kapadia. And young Kraffts, they were like volcanoes of the Middle Ages; we only know fables of both. Luckily, in the modern age, we got Kraffts – who recorded the volcanoes, and then we got “Fire of Love” and “The Fire Within” – which recorded the Kraffts.

Maurice and Katia Krafft visited various volcanoes of the world. The cameras could record only two things – the splendor and the danger; everything else is an interpretation. Interpretations of the landscapes and the personalities. The two documentaries not only focus on these images as a means to show the beauty of volcanoes but also as ends in themselves. Each frame tells the dual story of feebleness and fervor, of frailty and fascination when human lives are put in contact with the grandeur of nature.

Sara uses the original archival footage and images with a natural film grain, while Werner, now an expert in creating larger-than-life documentaries, focused on high-definition restoration of the footage. “Fire of Love” (2022) keeps the footage shorter with some narration in the background guiding the viewer like a friend.

“The Fire Within” leaves the viewer for longer durations with an operatic and classical background score emphasizing the timelessness and grandiose of images. Sara further used a smaller aspect ratio of 4:3, like that used in silent era Hollywood movies and early television, compared to Werner’s wider ratio of 16:9 associated with more modern viewing methods like HDTVs, computer monitors, and streaming websites like YouTube.

Related Read: The 10 Best Documentaries Of 2022

As Marshall McLuhan said, “The medium is the message”, Sara sees the Kraffts through a nostalgic and amorous lens and emphasizes their romantic relationship. Whereas Werner understands them in a modern setting and as fellow filmmakers, not just volcanologists. Sara does it too, but Werner went into the depths of this intertwined nature of performance and passion. After seeing their footage, Werner Herzog pointed out that, as the camera started rolling, they would start a performance.

They would wear outrageous helmets and take multiple takes of moments in distress, not because they were charlatans but because that’s the nature of the camera. It demands a performance that makes the rolling of the reel worthwhile. Like a God who would demand sacrifice in lieu of his presence. Even then, they would find moments like riding horses, being recorded on their fixed quota of film for no apparent reason. That’s when they were free.

Meanwhile, Asif Kapadia mostly uses the archival footage from broadcasts and interviews with minimal narration of his own to create an experience which feels closer to the subject, i.e., Senna. In the director’s commentary, they explained that while the footage was not of great quality, they did a lot of technical work on the sound design to give the documentary a ‘feature film’ feel. They mentioned how the quality of archival footage got better over time, and that showed a gradual unconscious passing of time in the documentary.

Kapadia also didn’t use any “talking head interviews” reminiscing about the old times spent with Senna; rather, the focus was purely on using actual footage to make the movie stand out from classical documentaries. From VHS footage shot by Ayrton’s younger brother Leonardo to an in-car camera that records what Senna felt during races, this documentary shows the beauty of frames in a different way. The frames are not symmetrical or follow a strictly aesthetic color palette. These are not carefully curated to look like paintings, yet there is a certain captivating beauty in the frames of this movie.

Senna was also famous for his on-screen presence and the passion he showed. He would kiss the interviewer, raise the Brazilian flag, and register his disagreements on camera. His rivalry with Prost was the beloved golden goose for broadcasters. After winning the Brazilian GP, he pours champagne on his head and raises the trophy even though he is in extreme pain and can barely lift his shoulders. But bearing the weight on his shoulders was probably the summary of his life. He kept going even when going was tough – motivated through passion, pride, presence of a higher power, and probably performance too.

Both the Kraffts and Senna were clearly extremely passionate – I’m not doubting that. But here’s where I am a bit confused, and something Werner also pointed out: some of it must involve a degree of performance, whether consciously or not. Maybe passion, by its nature, requires some element of performance, i.e., “showing” that you are actually passionate. Maybe performing passion creates a snowballing effect that renders your aim clearer, making you more passionate and thus maybe, just maybe, more performative.

Still, you could see how much their characters grew. What started with passion and love turned into a cause later. Kraffts started recording dangers to show how devastating eruptions can be and how prompt evacuation can save thousands of lives. Senna started advocating for regulatory changes for the safety of drivers. Australian conservationist and wildlife educator Steve Irwin once said, “If we can teach people about wildlife, they will be touched. Share wildlife with me, because humans want to save things that they love”. Irwin himself was a man of passion, dedicating his life to the sole purpose of saving wildlife.

Starting his career in front of the camera like Kraftts as a TV host for “The Crocodile Hunter”, he went on to have a similar cause of raising awareness using his passion and personality as a medium. His organization, “Wildlife Warriors,” continues to save thousands of animal lives to this day. Dedicating your life and possibly even your afterlife for the sake of changing lives is probably the purest beauty of passion.

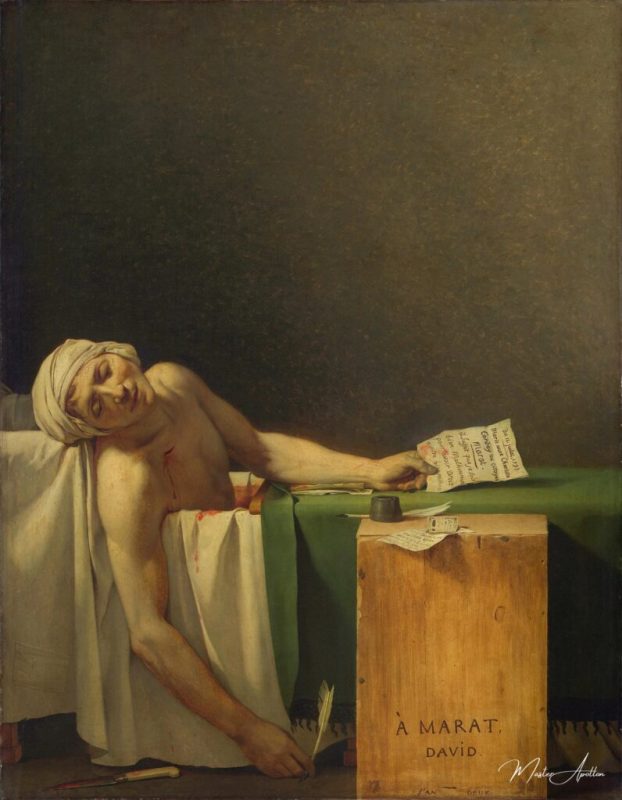

But everything comes with a price, and sometimes passion takes away the very thing it bestowed upon you – your life. We all know the story of Marie Curie, who was ultimately consumed by the glow of the very thing she discovered. In his 1793 painting “The Death of Marat”, Jacques-Louis David depicted the assassination of his friend, French revolutionary and radical journalist Jean-Paul Marat. As a vigorous defender of Sans-culottes (common people of lower classes of 18th-century France), he operated a periodical named “L’Ami du peuple” (“The Friend of the People”) through his savings, which placed him against the monarchy and with the radical Jacobins.

Also Read: The 10 Best Romantic Comedy Movies of 2022

You see, Marat had a skin condition, which caused him to spend much of his time in a bathtub. He would often work there, writing periodicals criticizing the ruler and channelling the revolts. Eventually, that’s where he died. Charlotte Corday fatally stabbed Marat after a 15-minute interview about Girondins. She didn’t attempt to flee. His legacy is more complicated. While he was against monarchy and upheld ideas similar to modern democracy, he is also blamed for the September Massacre. During her trial, Corday would say, “I killed one man to save 100,000.”

But at some point, Marat must have realised the danger of his work and his passion. Kraffts, Senna, and Irwin surely did. Right at the start, we saw Ayrton’s mother praying for his safety even before he made his F1 debut. Senna would contemplate quitting after seeing accidents of his fellow drivers, but didn’t – out of passion and out of love.

Katia once said, “I follow him because if he’s going to die, I’d rather be with him.” Not only did Kraffts know they would die, they also wanted to die doing the thing they loved, together. On 4th September 2006, Steve Irwin died from an injury caused by a stingray while filming an underwater documentary in the Great Barrier Reef. His passion took him away. But as he once put it, “I have no fear of losing my life – if I have to save a koala or a crocodile or a kangaroo or a snake, mate, I will save it.”

Even after knowing the dangers, none of them quit. Their passion and a higher cause didn’t let them. Senna once said, “I was not ready to give up my objective, my passion, my life. It is my life.” It is this never-ending laugh in the face of death that led them to the highest levels of glory. They all were standing at Mount Olympus of humanity. And they left a godlike legacy behind them.

Numerous awards bestowed upon various institutions and organisations named after them, yet their greatest legacy stands in how they affected the lives of upcoming generations. Curie paved the way for modern technology, Marat did it for modern democracy, Kraffts brought human lives in volcanic areas forward, and Irwin did it for wildlife. After Senna died, a Brazilian woman said, “Brazilian people need food, education, health, and a little bit of joy. And now that joy is gone.”

Icarus was a young man who escaped the cruel imprisonment of King Minos with his father Daedalus, using human-made wings. Though today Icarus’ story is seen as a moral warning against carelessness, their efforts and flight are second to none. They didn’t have the gifts of god like Hercules; all they had was passion and unrelenting desire to get themselves free.

Icarus went too close to the sun, Senna drove too fast, Kraffts stood too near the eruption, Curie spent too much time with radium, and Marat made too many enemies. But for some time, no matter how little, they all were flying. For some time, they all were basking in the glory and warmth of the sun. Icarus felt the glow of sun on his skin, Senna saw god at high speeds, Kraffts reached the outskirts of the world, Curie defied the patriarchal order of science, Irwin befriended the deadliest claws and jaws, and Marat brought a whole goddamn monarchy down.

They all flew. And the world flew with them. They gave up their fun, their ego, their youth, and even their life. They also knew they would fall. But they fell in glory, in respect, and in awe. The beauty is not in the flight or the fall, it’s in the knowledge of impending doom and yet giving it all you’ve got. They knew they would die. And that is the Morbid Beauty of Passion.