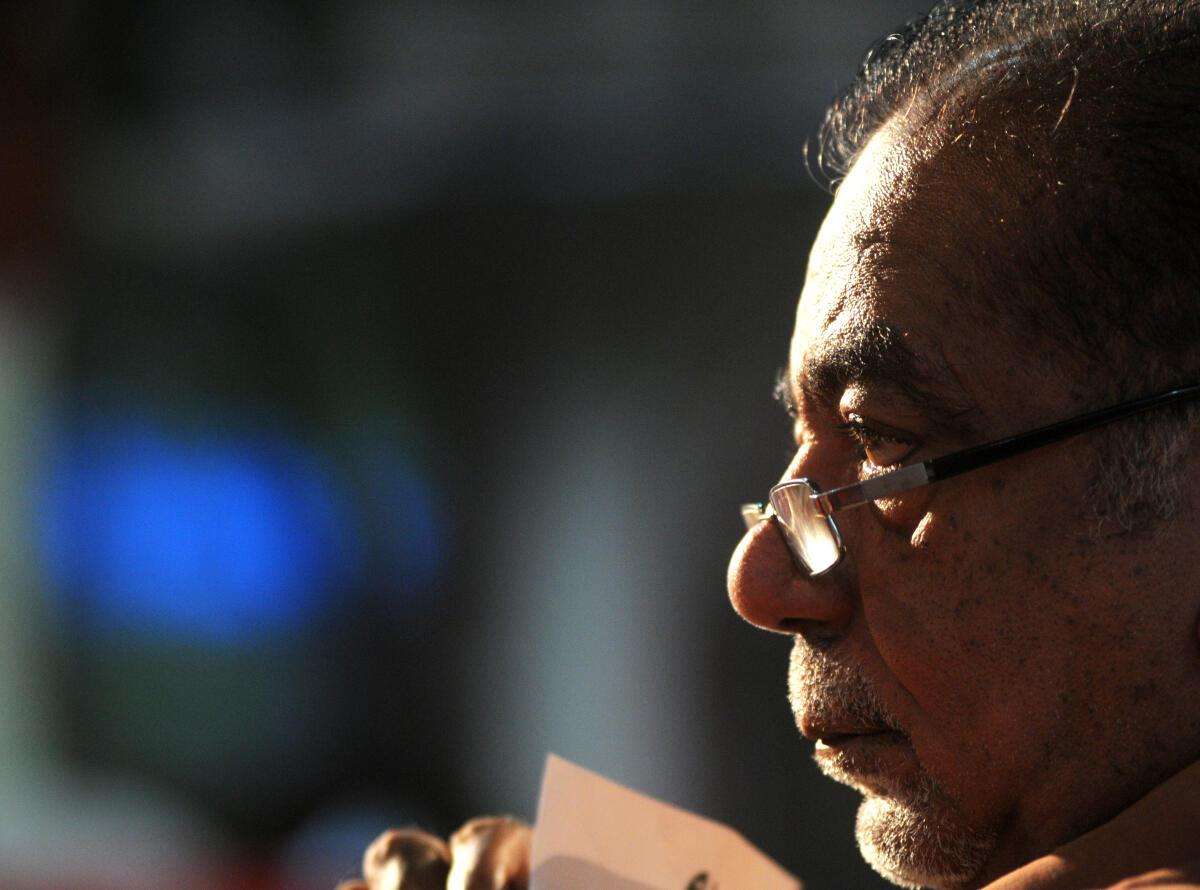

If there is one diegetic device that film viewers associate with K. G. George, the renowned Indian director of Malayalam language films hailing from Kerala who passed away recently on September 24, it must be the flashback. Indeed, George titled one of his films Lekhayude Maranam, Oru Flashback (Lekha’s Death, A Flashback, 1983), though reconstruction and retelling via flashback is a structural principle in several of his films. Most notably, flashbacks organized his first directorial venture, Swapnadanam (Sleepwalking, 1976), and was revisited in later films such as Yavanika (The Curtain, 1982), Kathaykku Pinnil (Behind the Story, 1987), and Ee Kanni Koodi (One more Link, 1990).

George uses flashbacks as integral to the structure of his films, whereby his characters are shown as living immersively in their pasts, irreversibly in the grip of memory to such an extent that their past becomes the diegetic present in these films. The exception is Lekhayude Maranam Oru Flashback, where the flashback is external to the story; the flashback serves the audience and not the characters in the film. In the other films, flashbacks are integral to the characters and the film’s structure.

The familiar adage with a ring of truth to it – “character is destiny” – literally becomes the defining feature of these later films through the tight structural control of flashback as the preferred narrative mode to build and reveal character. The chronological forward movement of time in these films for viewers is a backward movement in time, script-wise. George’s craft as a director becomes visible in the unflagging pace of these films that reject chronological movement, preferring instead a vector of time running in two opposing directions in tandem consistently for almost the full length of a feature film.

While Lekhayude Maranam, Oru Flashback, Yavanika, Kathaykku Pinnil, and Ee Kanni Koodi all center around an unnatural death followed by a societal and police procedural that investigates these deaths, George’s first film, Swapnadanam is an ambitious and tightly told story of a temporal and spatial displacement. In this film, we can clearly see the blueprint of an enduring diegetic template of almost philosophical proportions that was to become the face of George’s films: the temporal and spatial connections between past and present.

Swapnadanam begins with a title card that tells us that one day, a man disappeared from a small town in central Kerala and that, after several weeks, he showed up in Chennai. The man does not know who he is, his name, his identity, or why he is in Chennai. The film is an exploration of this jump cut in space and time: who is this man, and why is he in Chennai? George uses the now discredited quasi-medical procedure of narco analysis or the administration of the so-called “truth serum” as a plot device to get this amnesiac to talk to a team of sympathetic doctors who decide to help the man regain his sense of identity.

Under the thrall of narco analysis, while the team probes his unconscious, the man travels back to his past through a structured flashback. In the first-person narrative of the flashback, we learn that his name is Gopi and that he used to be a medical doctor, disappointed in love, unhappily married, and given to terrifying nightmares. His memories are tightly controlled by these themes as he relays them catatonically to the medical team. The memories circle back to the precise moment when the man left his home and ended up in Chennai. The man relives one final, terrifying nightmare, depth within depth, as the doctors plumb the lower recesses of his psyche. The nightmare becomes his portal out of his past as his past becomes a residual therapeutic experience, freeing the man to move forward in the real, diegetic present.

Gorgeously shot in black and white by cinematographer Ramachandra Babu, George’s long-time collaborator, even with the stylized seventies patina to it, Swapnadanam lays bare George’s fascination with a cinema of memory-time, almost in the manner of survivors of PTSD whose relationship to the present is largely instrumental, and whose true existence is locked in a past that is their perpetual present. They are their memories; their face and body betray the weight of these memories. George’s characters, saddled with terrifying memories, and who live perpetually in the past as their present have a recognizable onscreen look; the women are often hunched over, their sarees covering their bodies tightly like a blanket, undone hair, bare faces, foreheads knotted, voice breaking, trembling and shaken.

Men, likewise, affect a performative, nonchalant masculinity that barely hides the terror of being found out and exposed for some transgression secreted away in their past. These characters look and act sick; George offers them no respite from their sickness. There is an uncanny physical and character resemblance between Swapnadanam’s Gopi, played by Mohandas, and Joseph Kollapally, played by Venu Nagavalli in Yavanika. Likewise, the women characters–Jalaja’s Rohini in Yavanika, Devi Lalitha’s Vanitha in Kathaykku Pinnil, and Ashwini’s Kumudam in Ee Kanni Koodi–resemble each other physically and psychologically in their abjection.

In these flashback films, George is not so much retelling the same story as he is exploring various configurations of time as duration in relation to memories. Days, weeks, months, years – do memories fade? Do they lose their power over you? When does the present become rid of the past and become the authentic present? When is one free of the repetitive terror of the past? In George’s films, characters have nowhere to go, no certainties beyond the concrete facts of their lives, no loopholes or beliefs to redeem them, no deux ex machina. It is a bleak world with no easy exits.

Yavanika is an exceptional film in this regard. The time frame of diegetic action spans only a handful of days in this film. Yet, the enormous power of these few days is enough to disrupt the protagonist Rohini’s present and future in an irreversible manner. Flashback as a narrative and structural device is essentially repetitive and iterative, whether it is structured as one long, complete iteration as in Swapnadanam, or episodic retellings and displays as in Yavanika, Kathaykku Pinnil, and Ee Kanni Koodi. In a flashback narrative, the past is always tendentious and marked as opposed to a linear chronology. Each frame answers in a calculated manner the question: why are we here in the present like this? How did we get here?

If George had used the unconventional and dated trope of narco analysis in Swapnadanam, in Yavanika, he uses the intermedial qualities of cinema itself, in particular, cinema’s shared characteristics with theater, to plumb the depths of a crime and the psyche of those who perpetrated the crime.

Yavanika tells the story of the disappearance and murder of a debauched tabla player, Ayyappan, represented onscreen with a ferocious and vivacious intensity by the Malayalam actor Gopi. The disappearance opens the film with the rest of the film structured as a whodunnit with the chief investigating officer, played by Mammootty, interviewing Ayyappan’s coworkers and actors at Bhavana Theaters where Ayyappan worked, visiting crime sites, and theorizing the who-how-why of the murder. Character revelation through flashback inches its way toward a certain kind of existential truth; it cannot be hurried.

George is confidently aware of this. Thus, in Kathaykku Pinnil and Ee Kanni Koodi, he repeatedly revisits scenes from multiple perspectives, the so-called Rashomon effect, to arrive at the truth of a circumstance or an event. But beyond multiple perspectives lies the problem of ascertaining who is telling the truth. Thus, George’s reliance on an element that overdetermines itself—the narco analysis in Swapnadanam, the repeated attacks on the same woman by the same gang of men in Kathaykku Pinnil, and the relentless persistence and empathetic positioning of the police officer in Ee Kanni Koodi. These overdetermined elements are necessary to establish cinematic truth in murder plots.

In Yavanika, the element that does not compute, the aspect that overdetermines itself, is the theatrical performance itself. George self-consciously builds in a contrast of modalities between film and theater right from the start by devoting a significant portion of the diegetic time to the drama Karuppum Veluppum (Black and White) being performed by the actors of Bhavana Theaters in different locations in Kerala.

Lengthy sections of the film feature the rehearsals, the spectators anxiously and not so patiently waiting for the drama to begin, Rohini fumbling her lines, her missteps on stage in real-time, the scuffle between the drama troupe owner and the sponsors, the drama troupe’s bus and their trips, the internal bickering between members of the group, the make-up and costuming of the actors et al. In other words, the world of the drama troupe and the drama itself on stage achieve the status of a certain kind of material truth in real-time, a reified authenticity within the world of the film.

In the closed-room murder mystery of “Who Killed Ayyappan?” when the murderer finally admits to killing Ayyappan in real-time, on the drama stage, the film viewers know we are hearing the truth because a drama performance is ‘real.’ Unlike films that are made inside a production studio, both mistakes and truth are real and costly for dramas. The truth lies in us, the spectators, buying into the relationship between drama and truth. You can only speak the truth on stage in front of a real, live audience.

This is why Hamlet confidently asserts in Shakespeare’s drama, “The play’s thing/wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king” (Hamlet, Act 2, Scene 2). We have willingly accepted the truth of drama within the artifice of cinema. Each iteration of the lie spoken by the perpetrator in recreated flashbacks for the police officer explodes into the truth on stage in front of the world, so to speak. It is a brilliant coup.

In his mastery of cinematic form, George never imitated himself. He took risks with each of his screenplays on how best to portray cinematic truth, insistently circling over the potholes of cinematic lies. If we respond to his films with an appreciation of what we consider to be their honesty and authenticity, it is not merely because of their content but also because of his careful and confident experiments with form.

Read More:

50 Years of Nirmalyam (1973): Timeless, Introspective, and Radical

Analysing the ‘New’ in Malayalam’s New-Generation Buddy Movies: Rani Padmini (2015) and Super Sharanya (2022)

From Provoking Anger to Evoking Nationalism: The Alarming Evolution of Propaganda Films In Bollywood in the Past Few Years

![Lookback at Bresson: A Man Escaped [1956]](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/A-Man-Escaped-highonfilms-768x576.jpg)