“I am always homesick.” We often come across certain terms that appear extremely easy for anyone to grasp, but seldom do we delve deep into the fundamentals of the word, which apparently might offer more conflicting and sensitive ideas than expected. This piece will try to focus on a commonly used term and how it has been explored in popular media. ‘Home’ is one such word we perhaps use more often than we even breathe, but we hardly try to excavate the concept of the word and politics underneath it. What is home? What defines home? Is it physically constructed, or is it present inherently within? With ‘Autumn Sonata,’ a classic European film directed by Ingmar Bergman, as our talking point, we will aim to problematize these ideas while also exploring how the presence or absence of a ‘home’ may affect human existence and relationships.

‘Autumn Sonata’ is a Swedish drama film released in 1978. It was written and directed by Ingmar Bergman and had Ingrid Bergman and Liv Ullman In the lead roles, portraying the problematic relationship of a mother and her daughter. The story follows the return of Charlotte (Ingrid Bergman), a renowned classical pianist, to her daughter’s residence after seven long years upon receiving an invitation from her daughter Eva (Liv Ullman). What was considered a fruitful return and a possible joyous reunion after years of separation turns out to be a hostile encounter between Charlotte and Eva, as both try to assess their estranged relationship, unearthing painful secrets from the tumultuous past.

Bergman has craftily incorporated the vulnerability of the main characters without empowering one over the other, thereby not allowing the audience to penalize one and sympathize with the other. Charlotte and Eva’s conversation might remind one of a similar situation of estrangement in a famous play, ‘Top Girls’ (1982) by Caryl Churchill. In that play, Marlene, an ambitious woman in order to be successful, refuses to take up the responsibility of her child and leaves her with her own sister. While she went on to prosper and promote herself in society, Joyce, Marlene’s sister, had to take care of Marlene’s daughter, Angie, resulting in the loss of her unborn child from the stress.

This dichotomy of fame and family is also recurrent in “Autumn Sonata.” Charlotte has always been this aspiring, ambitious pianist who only dreamt of achieving success in life: running towards fame, popularity, and recognition. In pursuing success, she vehemently neglected the essentials of the mother-daughter relationship, which strained her relationship with Eva.

Therefore, Eva became isolated- devoid of any love from her mother and could only find assistance from her father. Charlotte’s abandonment of motherhood caused Eva to bear this tedious process of growing up alone. She lacked the sense of belonging, affection, and love from her mother. She even went on to blame Charlotte for her ignorance and pomposity. Eva could not identify anything ambiguous from what Charlotte said: she was addressed ironically as a “darling little girl” when actually Charlotte was tired of her. This gap increased to an extent where they found it difficult to reconcile.

What this article began with might find its relevance here. What is home? Nobody can offer any constructive definition of the word except that it may indicate certain senses: the sense of belonging, responsibility, familiarity, affection, and security. Home is where one might feel ‘needed’ or ‘longed.’ A home does not need to be made from materials like a house is constructed. It is a shelter that anybody can provide with unhindered love and affection. Harold Pinter wonderfully dealt with this concept of ‘home’ in his two-act play ‘The Homecoming (1964).

In ‘Autumn Sonata,’ Eva longed for that home. She stays with her husband, Viktor, a caring, responsible individual, and also cares for her disabled sister, Helena. She’s trying to provide security and comfort to both of them, particularly to Helena, owing to her illness. Whereas in reality, she has been deprived of that homely feeling throughout, owing to her mother’s ignorance.

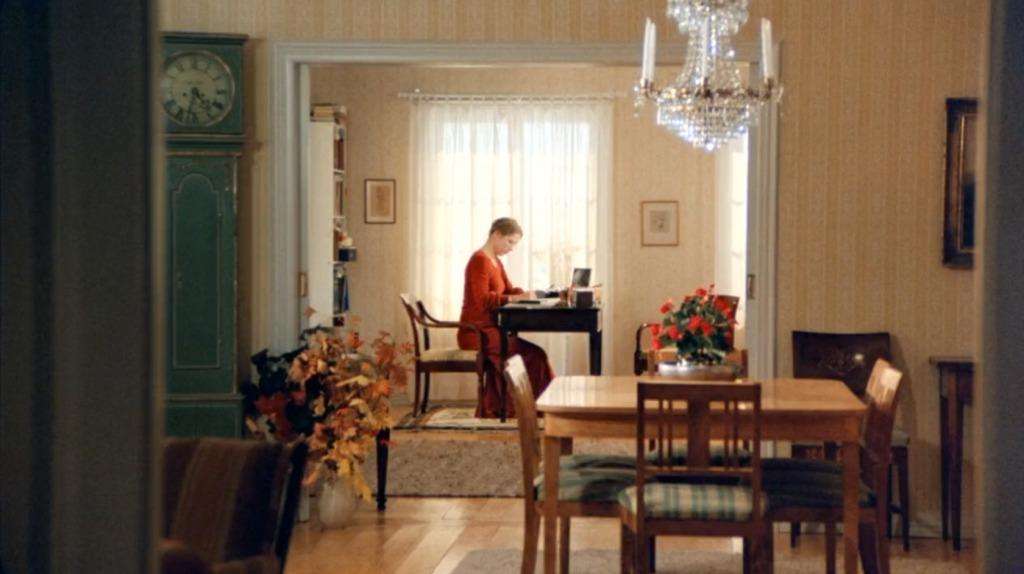

Eva remained ‘unfamiliar’ with the surroundings and the environment, which was propagated by her mother. She suffered from inferiority in the presence of her mother- she lacked the power to feel ‘needed.’ She went through emotional turmoil because she could not live up to her mother’s expectations, losing her first child, Erik, whom she conceived at a young age. The film, technically, through camera work, also captured Eva’s state of detachment with her staging in a frame-within-a-frame format at the beginning when she was writing the letter, thereby generating considerable distance from the camera, denoting her apprehensive nature and the state of loneliness and isolation.

Now the question is- does this lack of belonging occur suddenly to just one person? Or, can it be possible that this sense of longing has its own lineage? Can Charlotte be entirely blamed for her irresponsibility as a mother? As mentioned earlier, Ingmar Bergman did not try to prove one superior over the other. He emphasized the simultaneous suffering of both characters from the same ailment of isolation and detachment. One must have its own origin, and what seemed to be like an emphasis on the ‘effect’ portion in the film’s initial segment turned out to be just a figment of the bigger problem. Eva rightfully states: “You managed to injure me for life, just as you are injured.” In the lengthy monologue, Charlotte also confesses to emotional estrangement from her parents.

Charlotte never came to experience the comfort associated with her parents, which became evident from her saying, “ I don’t remember my parents ever touching me, caressing me, or punishing me.” She was alien to the emotions of tenderness, care, and softness; she did not know anything about love. Charlotte’s confession became more painful as she even questioned her own existence, triggering the corrosive feeling of just ‘existing’ without any purpose. In this situation, music became her only respite, which could help her express her feelings.

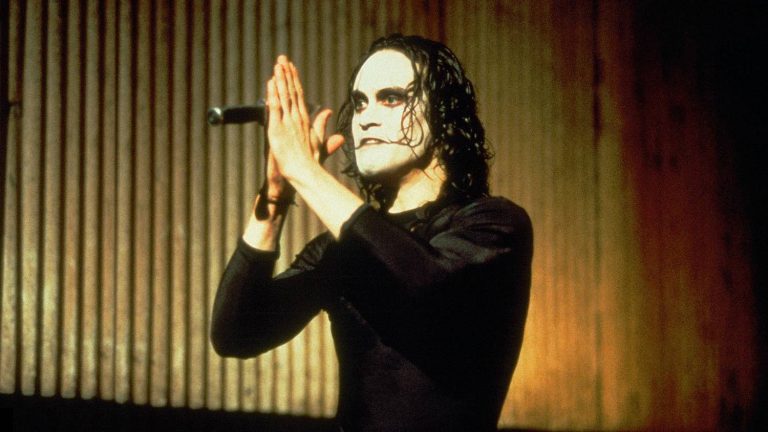

Viewers here can relate to her pursuit of achieving excellence in music more than anything. Music was her ‘Home,’ and she excelled in embracing that. She even expected her daughter Eva to comfort and assist her, but she never received that. Moreover, she did not expect Helena, her disabled child, to be at Eva’s house. Charlotte is reluctant to meet her but puts on a false facade to appear happy while meeting Helena. This behavior might seem rude and arrogant in the beginning, but it symbolizes her pursuit of evading the disturbing past life that she had. Helena represented her damaged childhood. This entire history of detachment and alienation perhaps tempted Bergman to employ repeated close-up shots of Ingrid, thereby delving deep into her psyche and mindset.

Bergman, the film’s writer with sheer brilliance, introduced some metaphorical lines that might not strike the audience initially but, with gradual progression, will sound highly symbolic of the character’s predicament. For example, from the beginning, Charlotte exclaimed that she had some “pain in the back,” which prevented her from practicing for a more extended period. As the film progresses with the tonal shift of Ingrid Bergman’s character, the same sentence comes back with a notion of her painful past life, which hardly provides Charlotte any emotional stability. Any child’s backbone is her parents, and Charlotte didn’t have such a support system.

Bergman skilfully transformed this supposed physical ailment into an indicator of emotional vacancy. By the film’s third act, viewers can identify the existential crisis of both the mother and the daughter; both expected care and comfort from each other, but to no avail. This triggered their loneliness, which they found hard to overcome. Home, for both of them, was missing. One might argue that Charlotte’s predicament is more painful than her daughter’s, owing to the long life that she had lived devoid of parental care and her daughter’s affection. But it would be an injustice to compare and quantify their state of insolvency.

With the title ‘Autumn Sonata,’ Ingmar Bergman provided an essence of ambiguity in conferring the consequences. Charlotte repeats a particular line throughout the film, emphasizing, “I am always homesick,” perhaps with the hope that somehow, someday, everything will be reconciled and she will get back to her home and will be blessed with long-lost comfort and peace, which even her fame and popularity could not offer.

On the other hand, Eva wrote an apology letter to her mother out of repentance after she left their house abruptly following the open confrontation. Here, the camera appears to be even farther away from Eva than in the beginning, constricting her within a more intimate frame-within-a-frame format. This enforces her subjugated state of mind, as she is now equally apprehensive and apologetic, hoping that the letter reaches her and Charlotte will forgive her. Charlotte’s face suddenly appears on the screen- not sure if she actually received and read the letter or if it is just a figment of imagination, with Viktor and Eva visualizing Charlotte reading the letter.

Does ‘Autumn’ bring harvests of happiness, reconciliation, and peace in the lives of Eva and Charlotte, or does it symbolize the further decay of their relationship? It is up to the viewers to interpret. ‘Home,’ after all, can only be resurrected with the labor of love from both sides, with perfect balance and equilibrium maintained, and not through lopsided commitment. Endless possibilities can be woven with both rejuvenation and decadence, going hand in hand with the flow of life with that one singular belief:

“We never give up hope, do we?”