Video essays can enhance a viewer’s ability to perceive the different aspects of visual story-telling. In this video essay – the link provided below – I take an in-depth look at Costa-Gavras’ classic political thriller Z (1969). Z is a hugely entertaining film, which established and improvised lot of narrative and visual tropes that later became inherent part of political cinema. In fact, the 1960s was bursting with radical energy and revolutionary fervor. Therefore, to comprehend the brilliance of this movie, it’s also important to understand the political landscape of the era and how that influenced the movies of the decade.

Massive political upheavals were happening across the globe in the 1960s. The last of the European colonies were crumbling. At the same time, the Cold War at its peak. Though the alleged ideological conflict didn’t lead to direct military struggle between US and Soviet Union, both the nations initiated or participated in many proxy wars that were scattered across the world and cost millions of lives. Elsewhere, people were fighting against different forms of economic imperialism. It was also the era of Rock n’ Roll, Civil Rights Movement, space race, Mao’s brutal Cultural Revolution, Prague Spring, and so on.

Naturally, cinema remained a pivotal tool to reflect the raising political consciousness of the decade. Some of the monumental movements in the history of cinema were flourishing in the 1960s. The French New Wave, Czech New Wave, and the Japanese New Wave were characterized by its unique artistic approach, set in the largely contemporaneous backdrop of social and political change. Political expression was reaching new heights in the Italian cinema of 1960s. The post-Neorealist Italian filmmakers like Francesco Rosi, Mario Monicelli, and Ermanno Olmi were perfectly capturing the cynicism and moral grayness of the era.

In 1963, revolutionary artist and Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembene made his 20-minute short film, Borom Sarret. Sembene – the novelist, former soldier and dock worker – was later known as the ‘Father of African Cinema’. He battled against censorship and racism to make radical art that indicted the neo-colonial African society. The new generation of political-conscious filmmakers hailing from Latin American and Africa led to ‘Third Cinema’, a cinematic movement born within the recently decolonized Third World nations. And these visually unsophisticated films powerfully zeroed-in on the themes of poverty, class, violence, identity crisis, and political oppression.

Hollywood’s highly commercialized studio model and aesthetic conventions were considered as the ‘First Cinema’, whereas the European art-house cinema that challenged Hollywood by bringing forth fresh aesthetic and formal techniques was addressed as ‘Second Cinema’. Third Cinema borrowed a little from the European cinematic traditions, but sought to free itself from the artifice of dominant cinematic practices of the time. The term ‘Third Cinema’ was first coined by Argentinean filmmakers Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino.

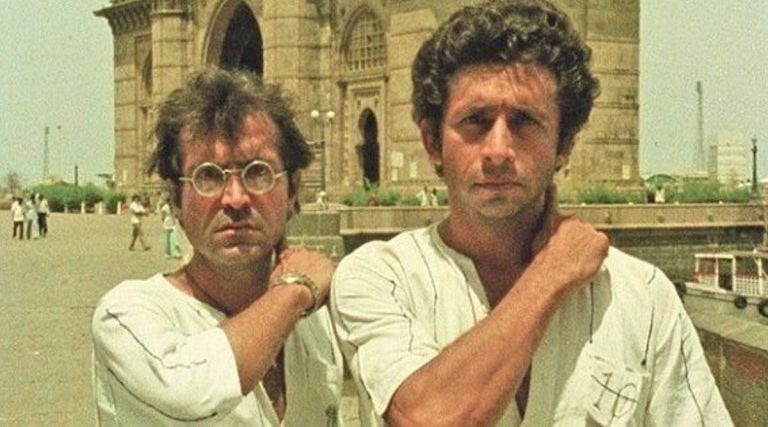

One of the films that deeply influenced Third Cinema and caused a paradigm shift regarding the notions of political cinema was Gillo Pontecervo’s Battle of Algiers (1966). It employed film art to give voice to the people’s struggles. The film laid bare the root causes of social injustice; the causes which still remain relevant in our conflict-ridden world. The other great political cinema that defined this decade was Z (1969). It strangely and sadly reflects our uncertain contemporary times, where the power-mongers have only grown more bold and shameless.

Now let’s find out more in the video below on how Costa-Gavras crafted the timeless tale, which brims with righteous sense of anger and outrage: