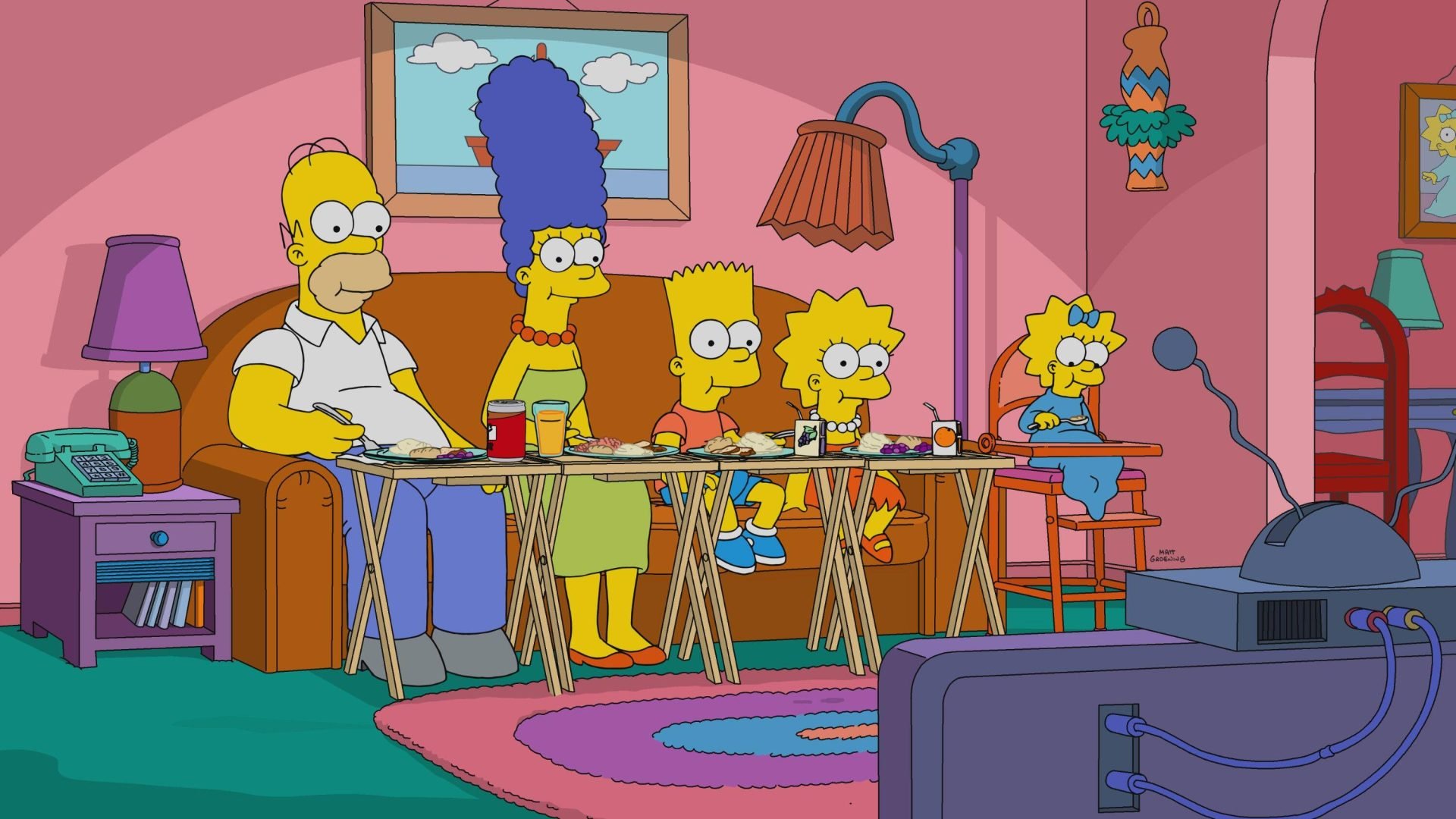

Anybody that hasn’t been living under a rock has heard of The Simpsons. Created by Matt Groening, the first episode about a dysfunctional, yellow cartoon family aired on December 17th, 1989, and has since proliferated into 740 episodes. Audiences of the 90s might remember how incredibly popular animation was generating a sort of “Simpsonmania” like a TV equivalent of the 1960s Beatlemania. Merchandise such as Bart Simpson’s Guide to Life (1993) or the Hit & Run video game (2003) stacked the shelves (and very quickly left them) as viewers fell in love with the anarchic black comedy that stood out in a beige world of tame, predictable sitcoms.

Simpsonmania has now well and truly passed, with most people remembering the show fondly as a counterculture icon of the past. It’s as if the show ended decades ago and isn’t still churning out limp episodes as the sell-out it promised never to be. Increasingly nonsensical storylines, product placement, lazy jokes, and an over-reliance on celebrity cameos have led to what is now known as “Zombie Simpsons.” So how did such a successful, clever, and universally loved show become such a cheap commodity? There are tons of factors, and although there isn’t one particular point it went from good to bad, there’s certainly a pattern of decline we can follow.

Why was it so good?

For people to care so much about why The Simpsons went so terribly downhill, it must have been pretty great, to begin with. How did a silly little animation capture millions of viewers every week? Firstly, it was one-of-a-kind. Most sitcoms focused on upper-class families (Full House, 1987; Seinfeld, 1989), reinforcing traditional American values, like obeying the law, putting your family first, and doing the “right thing.” Queue: yawn. Of course, these shows had their comical moments of conflict, but they were cautiously moral and docile overall. The Simpsons, however, was the complete opposite.

Before starting work on The Simpsons for Fox Network (who the show meta-textually makes fun of constantly), Groening caught the attention of Hollywood with his comic strip Life in Hell. First published in 1977, the angsty comic explored social alienation, bitterness, and doom through a comical cartoon lens. Its rebellious spirit was then passed onto The Simpsons, fine-tuned by Sam Simon and given the depth and form needed for TV by James L Brooks. We see these three names on the family’s television after the opening gag.

The Simpsons started off as a satirical cartoon about suburban American life, unfolding in the fictional town of Springfield. The Simpsons were the nuclear family focal point (parents Homer and Marge; kids Bart, Lisa, Maggie, and their two pets), though many other residents had their own individual storylines. Nowadays, at least one member of the Simpsons must seemingly be present in every scene, stealing away the rest of the characters’ autonomy.

At first, The Simpsons was an inversion of other 80s sitcoms, depicting a lower-middle-class family always on the brink of chaos. Shady characters, unruly kids, bullying, booze, fights, sarcasm, schemes, and mocking pop-culture references are all normal in Springfield, forming a sort of hyperbolic realism that subtly ridicules the sitcom genre (and our society in general). Crucially, though, The Simpsons still had a moral backbone, consistent character development, redemptive conclusion, and touching moments of pathos that could easily bring us to tears.

A lot of the show’s humor was derived from its intellect. You won’t find any fake laughing tracks added in post because each joke is far too vast for a single punchline at the end. At least, that’s how it was in the beginning. So where did it all go wrong? After winning 11 Emmys and a Peabody Award during its Golden Age (seasons 2-8), The Simpsons shot down from 22 million viewers a week to 1.95 by its 33rd season. It essentially turned into the type of show it always raised its eyebrow at. No longer a parody but the real thing.

Zombie Simpsons

Compared to the original fuzzy-lined, square-ratioed cel animation, The Simpsons is now a crystal-clear digital widescreen that’s lost all its flair. The characters are no longer themselves but hollow caricatures that act out of sync with their original personalities. Caricatures whose actions are tedious stepping stones to build up a flat, one-dimensional joke. This process even has a name—“Flanderization”—which we’ll get into later.

Up until season 10 of The Simpsons, you rarely saw a character using the internet or a computer, despite most people having one by 2000. This maintained a distance between the story world and ours—a much-needed distance to enjoy the satire and wit of the show. We can see this when Homer first discovers the internet in Das Bus (S9:E14). As usual, Homer has no idea what he’s doing when making the internet company “Compu-Global-Hyper-Mega-Net.” Groening uses this to make a dig at the wealthy (and corrupt) 1% when Bill Gates arrives to destroy his fake office. “Mapple” first appears in MyPods and Boomsticks (S20:E7), founded by Steve Mobbs in the most unimaginative, overt reference to Apple we could imagine. From then on, The Simpsons runs on blinding product placements, with the whole family committing themselves to technology rehab.

In this same episode (Screenless, S31:E15), Homer can even be seen playing the real iOS game Tapped Out. Talk about indiscrete marketing! We’re sure that if you showed the original animators the Tik Tok intro to To Surveil with Love (S20:E21), they’d be horrified at the show’s soulless indoctrination into trendy society. That said, Groening remains the creative consultant of The Simpsons when he’s not distracted with other projects like Futurama (1999) and Disenchantment (2018).

The widespread hate for Zombie Simpsons, plummeting viewer stats, and absence of many original cast and crew members (Marcia Wallace, Phil Hartman) aren’t putting Fox off from making more. Ultimately, The Simpsons have a cult status that keeps enough people tuning in to turn a profit. Younger generations that have never seen the original show (which is now targeted at empty-headed teens rather than intellectual adults) aren’t aware of its downgrade. Producer Mike Reiss insists that “to give up on the show is to say we’ve explored everything human beings can do,” but all we can hear is cha-ching.

Flanderization

Flanderization is a term that can be applied to any TV show but originally stems from The Simpsons. Namely, the friendly-turn-fanatic neighbor Ned Flanders. It refers to when a character (usually cartoon, but it can also be seen in shows like The Office, 2005, where Dwight becomes a parody of himself) progresses into an empty, exaggerated version of themselves. Certain traits or features are inflated over time until it completely overtakes the character, such as the Christian aspect of Flanders overtaking his kindly mild-manners, making him a bible-thumping religious fanatic.

Of course, no character is fully developed from the beginning. They gradually progress and evolve into something more concrete and finalized. You need only look at season 1 to find—on a basic aesthetic level—characters sport different hair colors (Moe Szyslak, Barney Gumble) or even different races (Waylon Smithers). However, once a character has found its footing as a fleshed-out human, you can’t successfully make them act differently unless weighed out by the Rule of Funny. A rule The Simpsons ends up discarding altogether. Let’s look at some examples:

Homer Simpson

Homer begins season 1 as a strict disciplinarian, which gives way to a slightly more lenient (if still hot-headed) parental figure. This is mainly because he’s too dumb, lazy, and distracted by the TV to punish (or notice) his children. Homer is dopey but not completely brainless; he’s extremely lucky for someone, so accident-prone and adores food and beer. Homer is also very emotional, furiously strangling Bart one minute and giggling like a little girl the next. This allows him to feel enough love and guilt towards his family that he always redeems his vices, such as working two jobs to buy Lisa a pony (Lisa’s Pony, S3:E8)

In recent seasons, Homer is an utterly selfish buffoon with no moral compass. He acts purely out of impulse or gratification, neglecting his wife and family without making amends. Whatever small brains he once had has depleted into mindless, iPad-scrolling mush. As Professor Lawrence Pierce puts it: “I think Homer gets stupider every year” (The Simpsons 138th Episode Spectacular, S7; E10). We can see a similar theme in Ralph Wiggum’s Flanderization. Although he’s always been the special needs kid in Lisa’s class, he could surprise teachers with things like his eloquent acting skills in I Love Lisa (S4:E15). Now he can barely string a sentence together.

Marge Simpson

Marge’s catchphrase isn’t a phrase so much as a sound. A grumbling sound of disapproval she makes under her breath. This sums her up completely: she’s sensible, cautious, and observational but also a bit of a doormat who probably, after so many years, knows there’s no point trying to stop whatever chaos is about to ensue. She’s way too good for Homer but brings out his lovable side, patiently accepting all his flaws and quirks. Around the 20-season mark, we begin to wonder why Marge married him at all, as by now, she’s completely done with his drama. In Wedding for Disaster (S20:E15), we see a bridezilla, Marge making unreasonable and angry demands or getting road rage in Marge Simpson in: “Screaming Yellow Honkers” (S10; E15). Both worlds are away from her original gentle nature.

Bart and Lisa Simpson

Bart and Lisa have always had their typical sibling rival that only occasionally gets out of hand (Lisa on Ice, S6:E8; My Sister, My Sitter, S8:E17). Their arguments are exasperated by the fact they are opposite people—Bart, a dim-witted daredevil, and Lisa, a school-loving child prodigy. For the most part, however, they team up to solve mysteries and problems together (like reuniting Krusty the Clown with his father in Like Father, Like Clown, S3:E6, or defeating Sideshow Bob repeatedly) and always makeup in the end (Bart writes Lisa a song for her birthday in Stark Raving Dad, S3:E1).

Lisa’s genius eventually became her defining characteristic. She no longer plays with Malibu Stacey dolls or calls the Corey Hotline but demonizes everything, protesting, lecturing, and hating everything she sees. On the other hand, Bart goes from an entertaining prankster inspired by Dennis the Menace to a complete sociopath. When Bart accidentally kills a bird, he keeps her eggs warm in his treehouse in penance, which he would never do now.

Saying this, Bart hasn’t been Flanderized as much as other characters in The Simpsons, such as Moe (creepy bartender and part-time criminal to obsessively suicidal but friendly neighbor) or Dr. Hibbert (reliable family practitioner to the king of malpractice, replacing Dr. Nick and handing out morphine here, there, and everywhere). Overall, Springfield and its people are not who they used to be.

Pinpointing its downfall

It’s impossible to pinpoint exactly when The Simpsons died, but most fans agree that The Principal and the Pauper (S9:E2) was the episode that signaled the end. Although there were still some amazing episodes to come, season 9 is considered the end of the show’s Golden Age, where characters began to get flatter and more absurd by the minute. Although The Principal and the Pauper does have a handful of hilarious, multi-layered gags, they can’t detract from the fact writer Ken Keeler destroyed the entire narrative arc in one fell stroke.

At the end of each wild episode, Springfield returns to its equilibrium. None of the characters age or change clothes; the Simpsons never permanently move out of 742 Evergreen Terrace. Homer remains working at the nuclear power plant despite causing so many near-meltdowns. You can fly the Simpsons family to as many countries and give them as many new careers as you want, but they’ll always land back in the same spot. On the other hand, certain plot points can’t be undone. For example, Marge will always be a gambling addict, and the deaths of Maude Flanders and Bleeding Gums Murphy will remain so. It would break the narrative logic to suddenly resurrect them—even in a cartoon.

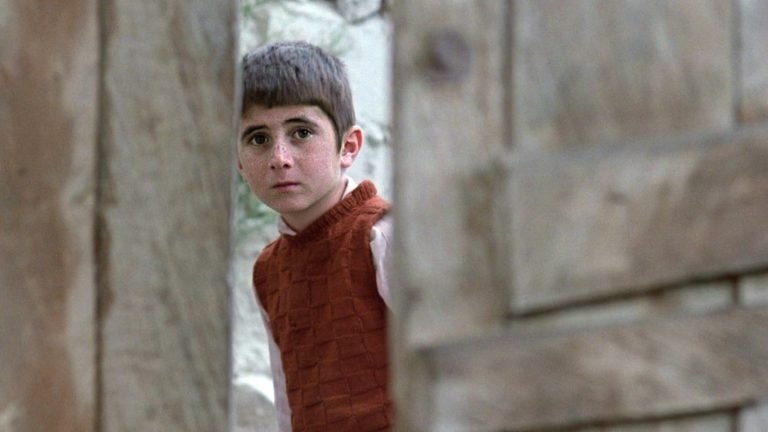

Principal Skinner is another character the writers killed off, except his was done metaphorically. When Keeler did try and pretend it never happened, it somehow made it even worse. Skinner is a recurring character and fan-favorite. He’s the milquetoast headmaster of Springfield Elementary that Bart considers his enemy (behind Sideshow Bob, of course) and exercises militaristic discipline—or at least, tries to. Deep down, though, Skinner’s a soppy mama’s boy that anybody can walk over.

By season 9, viewers had dedicated eight years to knowing and loving the dwellers of Springfield. Then, suddenly, the writers pulled the rug out from underneath them and declared Skinner a fraud. When the real Principal Skinner arrives in town, it’s revealed that the one we know is actually a man named Armin Tamzarian. He served alongside the real Skinner during the Vietnam war, taken under his wing after joining the army as a petty criminal more akin to Bart. Tamzarian thought Skinner had died during the war, so he took his name and dream job as principal to fulfill his goals for him.

Now that the real Skinner is back on the scene, Tamzarian is kicked out of Springfield, only to be brought back again, and a court judge rule, “I hereby confer upon you the name of Seymour Skinner, as well as his past, present, future and mother.” The real Skinner is tied up and driven out of Springfield, while the judge further decrees that “everything will be just like it was before all this happened, and no one will ever mention it again.” So, not only did the writers take an axe to one of the show’s main characters, but they then asked us to pretend it never happened, rendering the destruction pointless. This is arguably one of the first instances of the show’s creative bankruptcy.

Harry Shearer, the voice of Skinner, said himself that this storyline was “so wrong. You’re taking something that an audience has built eight or nine years of investment in and just tossed it into the trash can for no good reason…it’s so arbitrary and gratuitous, and it’s disrespectful to the audience.” And just like the judge ordered, nobody did mention it again. Not even the creators. According to Shearer: “they realize it was a horrible mistake. They never mention it. It’s like they’re punishing the audience for paying attention.”

The only other time this lapse in judgment is acknowledged is in I, (Annoyed Grunt)-Bot (S15:E9) when Lisa is on her fifth pet cat and decides, “we’ll just call you Snowball II and pretend this whole thing never happened.” As she says this, Skinner walks past and interjects, “that’s really a cheat, isn’t it?” to which Lisa replies, “I guess you’re right, Tamzarian.” This joke is a double-edged sword because it requires context and knowledge to understand; it’s self-aware and almost acts like a nod—an apology—to the mistake the writers made in season 9. However, actions speak louder than words, and despite this acknowledgment, the creators still went on to corrupt the story and cheat on its characters.

Will it ever end?

The downfall of The Simpsons was a gradual decay into caricatures, product placement, flat one-liners, and Lady Gaga. It didn’t happen overnight. Season 14 saw the switch to digital animation and heavier employment of celebrity cameos. Unlike the early days when guest voices had their own unique, fully-fledged characters (Michael Jackson as Homer’s cellmate; Danny DeVito as Homer’s brother; Dustin Hoffman as Lisa’s substitute teacher), they now appear as themselves, usually at random and for only a couple of minutes.

Instead of parodying pop culture, The Simpsons is now the show that gets parodied. “I think I speak for all of us when I say, I am over The Simpsons…The Simpsons suck!” says Peter Griffin in Episode 1 of Family Guy’s 13th season. The Simpsons/Family Guy crossover was almost exclusively written by Family Guy producer Patrick Meighan, remarking on the universal opinion that The Simpsons has become stale, now replaced by its once-student Family Guy.

The Simpsons doesn’t make delicate references to books or movies anymore but bases entire episodes on them, likely due to a lack of imagination after running for 34 years (making it the longest-running sitcom and animation in American TV history). The writers have clearly run out of ideas, hence the increasingly chaotic and illogical plots where every storyline feels more like a Rick and Morty (2013) episode than a grounded family sitcom, disregarding all original rules of The Simpsons diegesis.

Despite all these overwhelming factors, The Simpsons remain the flagship show of Fox network who refuse to let their paycheques go. Season 34 is currently in the works, with at least two more seasons confirmed by the studio. The Simpsons have garnered an entire online aesthetic during the Internet age, with whole Instagram pages dedicated to screen grabs (@scenic_simpsons; @springfieldcuisine; and @existential.simpsons—note most of their posts are from old episodes…before it lost its charm) and GIFs of Homer backing to a hedge circulating like a forest fire. However, most fans waved goodbye to The Simpsons the day Principal Skinner died in 1997.