When in 2011 Hungarian Director Bela Tarr declared that ‘The Turin Horse’ (A torinói ló) would be his last feature film, no one doubted the decision of this critical darling. From the very beginning there was something odd or rather untraditional about his films. For some Bela Tarr represented a man stuck in a modern time, who came from an older European world of art and literature. A thoughtful rebel who was given a camera to tell stories and his last film doesn’t take the easy escape route from this image.

A film of sparse dialogue ‘The Turin Horse’ opens with a blank canvas and before we see anything we hear the narrator’s voice reciting the apocryphal tale of Friedrich Nietzsche trying to save a horse from the merciless whippings of his master. Nietzsche is so overwhelmed by this ruthless spectacle that he throws his hands around the horse’s neck and sobs violently. He is then assisted by his neighbor back home where he laid silently for two days and then finally utters his last known sane words “Mutter, ich bin dummin” (Mother, I’m a fool).

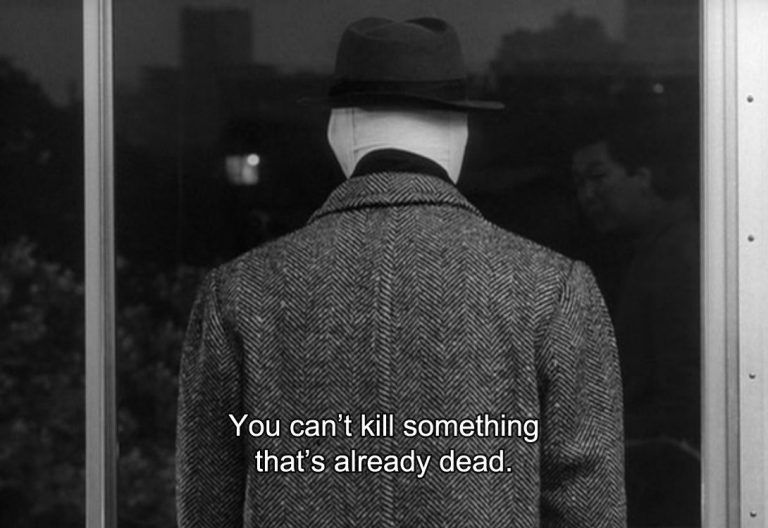

Seconds later we see the supposedly same horse. Screen is coloured with Bela Tarr’s favorite color palette, black and white. “There is a whole spectrum of color between black and white” he says, when asked of his choice to shoot all his work in 35mm shot and in stark black & white photography. It seems fitting that he continues with his usual trademark to his very last feature film before his camera turns to black entirely.

The very first visual image of “The Turin Horse” is an exhilarating experience. A beaten, defeated horse reigned by the handicapped hansom cab driver, surrounded by thick mist and raging winds. Camera zooms onto the horse from different angles, for a few seconds it rests on the driver itself but its central focus remains the animal. There is nowhere to escape, neither for the horse or the man nor for the viewers. For a good five minutes the camera solely focuses these two from different perspectives, all the while the haunting almost apocalyptic score of Mihaly Vig fills you with unexplainable dread. As the background score hushes down, we hear the sound of tired hoofs and the heavy breath of the animal. You can’t help but feel its pain, its resolve to give up and before you know it, your commitment to the story is locked in.

The Turn Horse featured in our list of 75 Best Movies of the Decade (2010s)

The masterfully curated cinematography of Fred Kelemen, a constant collaborator of Bela Tarr draws you straight into the fate of the horse and the cabdriver, and what we see ahead is the fictional and partly philosophical explanation to what happened to the horse. However, Bela Tarr would not be pleased with the word philosophical “Let’s not be too sophisticated?” he says, when someone readily tries to decipher the meaning behind his work.

The entire story is told in the span of seven days’ time. The narrative walks an illusionary parallel line between a simply told story of a potato farmer and his daughter who lives in a single room stone hut with an attached horse barn and a philosophical awakening on the director’s part. Each day is bounded by the same routine, we see their life unfolding in great detail, to the point where we understand how they live, how it is to be them but each day something changes. A life of repetitive routine where nothing changes but little by little existence becomes unbearable. The unrelenting raging storm that is deafening to ear is shut out by the withering door and inside life is silently crawling. The everyday change is so subtle but it mark’s the deepest impact in viewers’ psyche. The wood warms have stopped making sound, the father says “I have heard them for 58 years, but I don’t hear them now”

Bela Tarr’s last film is heavily shadowed by the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. The apocalyptic events that are taking place are not cataclysmic, they are the result of both God and men or so says the neighbor who comes to buy Palinka. Nietzsche believed that God is dead and all the consequences and bearings we have, are results of our own actions but Tarr takes a different route and assigns the blame on both God and mortals. The score is settled and it lies equally on both sides.

‘The Turin Horse’ mirrors the mental journey of its creator, who started his career with a lot of social anger and with burning passion to change the world, the burns of which are visible in his earlier work like ‘Damnation’ but as years went on Tarr realized that the problems he wanted to solve were far deeper than he anticipated. The root of our sufferings will always be intertwined with one another, nothing could be saved on its own.

The understanding of human pain and suffering had been a chief aim of Friedrich Nietzsche but he denied divine interference in it, Tarr in his attempt of releasing some of the pain understood the futility of this omission. God does take part he says, we dig our own grave by our own folly but he softens the earth for our burial. Let us go back to the very first image of the film, which was of the horse. Nietzsche tries to save the horse but what happened to it afterwards? Was it saved? Could it be saved without seeing the hands that reigned him? The raging storm in the film is the presence of that wreath, the final decay. The film marks the de-creation of the world, de-creation by fractions that is done by us and our many Gods. It may seem like a bleak way of looking at things but the film at its core asks for a more mellow approach towards life, it begs patience from both mortals and immortals.

Also, read – The Best films of 2021

The Turin Horse is an intricate study of human life, a discovery of what is unseen by the eyes. It’s an attempt to reassign the focus from ontology to cosmology. We see a beaten horse but don’t see the beaten men. Our actions are more layered then what they appear to be. The film seems to be Director’s declaration that he himself knows nothing and just like Nietzsche, he too comes to the natural conclusion of life. It’s an apt place to stop or rather start. Moreover, Bela Tarr’s ‘The Turin Horse’ is an epiphany and epiphanies can only be felt, not explained.

Author – Payal Baisoya

Bio – “Imaginary conductor of a round table interview with Bukowski, Layne Staley and Al Pacino, I am what they call a true realist.”