“Platonic minds expect life to be like film, with defined terminal endings; a-Platonic ones expect film to be like life and, except for a few irreversible conditions such as death, distrust the terminal nature of all human-declared endings.”

– Naseem Nicholas Taleb, “The Bed of Procrustes”.

For the mouths of cinema lovers who have stretched out their tongues to taste everything from Swedish to Iranian and African to Japanese cinema, Mukkabaaz turned out to be placid, lacking a tenacity that could grip your heart and land a punch right where it would hurt, fleeting in its narrative like a regular unnoticeable co-passenger on your everyday local train, like the elevator symphony (which you cannot distinguish from Beethoven but would label mediocre for the sake of it), unadventurous, devoid of metaphors and dialogues that can fit as the postscripts of sincere love letters, too ordinary, too realistic, not typical of Anurag Kashyap like Wild Strawberries was not typical of Ingmar Bergman and The Elephant Man was not typical of David Lynch.

For a country that has seen cinematic marvels like Sadgati and Fandry crafted on the eternal caste-divide, Mukkabaaz is too verbose and loquacious, needing to use the instruments of surnames to tell who from whom, over-emphasizing character development till a point the audience feels empowered to predict the screenplay, making the political so personal that the “intellectually bourgeois” class of audience feels nauseous because, for them, art is good art only if it can have multiple interpretations. Abstract and absurd is the new art-house, the only one. Susan Sontag calls it “programmed avant-gardism” when an audience looks down upon an artist because he left nothing un-deciphered to go home and mentally ruminate. It is a common misconception to believe simplicity cannot be profound. It might inhibit our acceptance of a film only because it speaks a language without a mystifying accent.

In her essay Against Interpretation, Susan Sontag writes,“ None of us can ever retrieve that innocence before all theory when art knew no need to justify itself when one did not ask of a work of art what it said because one knew (or thought one knew) what it did. From now to the end of consciousness, we are stuck with the task of defending art.” The prejudice of the elite obstructs the very establishment that modern cinema wanted to overthrow: standardization, constructs, restrictive definitions of what qualifies for “good enough,” a dissatisfaction (conscious or unconscious) with the work and a wish to replace it by something else. Mukkabaaz was reduced to the linearity of its content, while what makes it stand alone as a piece of art was missed, that is, the form rather than the content. It is a portrait of ordinary human life where politics, culture, and relationships intertwine and are entangled in an irresolvable, unyielding knot.

If I could put the movie in one line, it would be from Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground, “I say let the world go to hell, but I should always have my tea.” Amidst small-town vandalism and inescapable poverty, Shravan struggles for the simple luxury of employment. His identity is disputed in a world where exclusively the Brahmins qualify for legitimacy, and you can sniff out from only the casual conversations when only Chaubeys, Tiwaris, and Mishras are found seated in the majestic chairs charged with the power of authority. Families are only weaved together with the threads of bloodline and tradition. Politics follow your footprints to the extent of your kitchen, deciding your future and your diet. Despite the brutal clutches of circumstances and inevitable social conformity, love always slips out.

The love story of Sunaina and Shravan is a wordless one that does not fit into the conventional expectations from an “affair”; in it all that is understood is in the language of sacrifice and promises, where the seams of trust(well-knit with assuring reciprocation and inexhaustible love to pour into one another’s hearts) bask in the eternal sunshine of their spotless minds. But their fates are not equally spotless. The battle begins every time Shravan steps out of the boxing arena. Life knocks him out as many times as he gathers the courage to tighten his gloves- once when he resists accepting apprenticeship is synonymous with slavery, again when he mistakes a wedding for a happy ending, and again with the hard-hitting realization that government jobs are more about tolerance and hierarchy than discipline and honor, and for the final time when he realizes that some battles are won not by obstinacy but by compromise. That ambition is but a small trade-off if there is stability, love, security, and comfort on the other side of the table. At some points in life, you must have your tea, even if it means abandoning the hyped worldly pursuits of passion and success(or as one of the songs puts it, “Bahut Hua samaan, tumhari aisi this”).

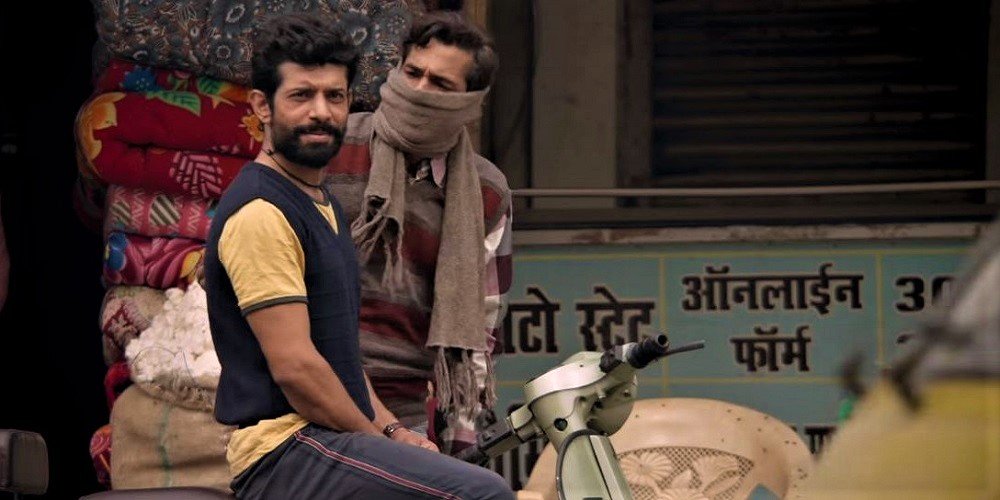

Every other character is but a resurrection built on the same matter, some with a mixture of empathy and less greed and some with more pride but still an equal fear of losing everything. In one of the scenes, a Yadav takes a video of a Thakur arranging empty teacups on a table and reminiscences, “At one time our fathers used to work under the Bhumihaars; look how the time has changed,” in a sentence framing the history and sociology of India. In another scene, two brothers talk about what makes a Brahmin the revered “upper” caste, only to realize neither power nor wealth but an imaginary ego-feeding sense of false pride. There are no shades of extraordinary hyperbolic absurdity with which the insignificant lives of the characters are painted, no allegorical signature of the director left behind in subtle nuances involving the furniture or the sky or shadows or reflections, no raining of frogs or Birdmen or resplendent references taken from classical literature, but a raw depiction of unexaggerated un-glorified slight town monotony with its scooters, its cracked walls aching for whitewash, its ugly sunsets that no one cares to write a quartet upon, the dust in its air which settles on every pair of eyes that ever cared to dream beyond the contours of the city, its sloppiness and shadiness, and struggle for survival.

In a world with plenty of Samuel Beckett, Thomas Hardy, Faulkner, and Proust, there is still a lot of space left for Jack Kerouac, Saunders, and Salinger. In the Indian context, read this film like a book by Aravind Adiga Jeet Thayil or Rohinton Mistry. “The old style of interpretation was insistent but respectful; it erected another meaning on top of the literal one.”, Sontag continues. “The modern style of interpretation excavates, and as it excavates, destroys; it digs “behind” the text to find a sub-text that is the true one. Today is such a time when the project of interpretation is largely reactionary and stifling. Like the fumes of the automobile and heavy industry, which befoul the urban atmosphere, the effusion of interpretations of art today poisons our sensibilities. In a culture whose already classical dilemma is the hypertrophy of the intellect at the expense of energy and sensual capability, interpretation is the revenge of the intellect upon art. To interpret is to impoverish, to deplete the world—to set up a shadow world of “meanings.”

Cinema, like literature, should be judged on absolute terms and not relatively; every work of art breathing a life of its own does not bear the burden of living up to expectations that are subconsciously institutionalized and impressed upon the minds of connoisseurs as some measure of merit, defeating the purpose of art being the complete opposite of confinement and scrutiny. An uproar overtook the country online and offline on the release of “Padmavat”, accusing the film of being misogynistic, Islamophobic, anti-Rajput and much more, missing the very simple point that morality is not the responsibility of art. Let art be a private affair between the maker and the consumer, both engaging in a discourse where no taste is bland and none too erudite, where all that matters is an intimacy and a connection that is beyond technicalities and dissertations. I remember watching “Mother!” by Darren Aronofsky, embracing the film as a narrative on the subconscious of an agoraphobic woman who feels predated by social interaction, only to realize all he wanted to portray was a social commentary on global warming. Sometimes, the intention and the consequence need not be aligned and not necessarily for the worse.

Andrei Tarkovsky proves my point in a much more straightforward way, talking about art as a spiritual journey rather than a conclusive debate: “Artistic creation, after all, is not subject to absolute laws, valid from age to age; since it is related to the more general aim of mastery of the world, it has an infinite number of facets, the vincula that connect man with his vital activity; and even if the path towards knowledge is unending, no step that takes man nearer to a full understanding of the meaning of his existence can be too small to count. Art must carry man’s craving for the ideal, must be an expression of his reaching out towards it; art must give man hope and faith. And the more hopeless the world in the artist’s version, the more clearly perhaps we must see the ideal that stands in opposition – otherwise, life becomes impossible! Art symbolizes the meaning of our existence.”

![[Watch] The Unexpected Popularity of RRR in the West Explained](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/The-Unexpected-Popularity-of-RRR-Explained-768x432.jpeg)