Like most fans of cinema, I enjoy reading a lot of reviews; not just to find a worthwhile movie to watch, but also to gain some insight and look into different perspectives on films that I find interesting. I especially like reading film reviews from the past to see how assessments back then measure up to how the film is viewed today, and to examine whether similar evaluations of the directors and predictions regarding their careers have aged well.

We all know how certain movies, like “The Thing” and “Blade Runner,” were poorly received during their time, only to become highly influential within their genres later on. But it’s even more fascinating to read why these movies were panned and what led to their reassessment. With that in mind, I would like to talk about eight reviews or assessments that I found particularly fun to revisit with the benefit of hindsight.

Andrew Sarris, The American Cinema

Andrew Sarris is considered a titan in film criticism. Credited with popularizing the auteur theory in the United States, Sarris wrote the highly influential book “The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929–1968,” where he evaluated films and directors from the advent of the sound era through the mid-20th century. One of the most fascinating parts of his book is this excerpt on Francis Ford Coppola.

Francis Ford Coppola is probably the first reasonably talented and sensibly adaptable directorial talent to emerge from a University curriculum in film-making. You’re A Big Boy Now seemed remarkably eclectic even under the circumstances. If the direction of Nichols on The Graduate has an edge over Coppola’s for Big Boy, it is that Nichols borrows only from good movies whereas Coppola occasionally borrows from bad ones. Curiously, Coppola seems infinitely more merciful to his grotesques than does anything-for-an-effect Nichols. Coppola may be heard from more decisively in the future.

To give you some context, Mike Nichols had just come off two back-to-back critical and commercial megahits in ”Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” and ”The Graduate” both of which combined had 20 Oscar nominations and 6 wins including one best director win for Mike Nichols. On the other hand, the films Coppola had made at that point weren’t particularly successful critically or commercially and have largely been forgotten even today. So for Sarris to predict that Mike Nichols would fade into irrelevance (which he again reiterates in the section he dedicates for Mike Nichols) while championing Francis Ford Coppola was certainly bold, to say the least.

But that’s exactly what happened in the next few decades. Coppola went on to have a career that far eclipsed Nichols who while reasonably successful was never able to recapture the magic of his first two films. While Sarris might not always be right in his predictions (Kevin Smith certainly didn’t become the next Scorsese), this was one of those rare instances where a critic drew attention to a genuinely underrated (at that time) talent.

Roger Ebert, Fanboys (2009) Review

If there’s one thing people loved about Ebert, it’s that many of his takedowns of terrible films are often more entertaining than the films themselves. He wasn’t known to mince words when he hated a film and as one should expect of a Pulitzer-winning writer, his negative reviews were filled with memorable passages. Whether it’s describing “Pearl Harbour” as a two-hour movie squeezed into three hours or “Armageddon” as a 150-minute trailer, we all have our favorite Ebert quote from his most scathing reviews and mine would have to be this one from his review of ”Fanboys.”

A lot of fans are basically fans of fandom itself. It’s all about them. They have mastered the “Star Wars” or “Star Trek” universes or whatever, but their objects of veneration are useful mainly as a backdrop to their own devotion. Anyone who would camp out in a tent on the sidewalk for weeks in order to be first in line for a movie is more into camping on the sidewalk than movies.

Extreme fandom may serve as a security blanket for the socially inept, who use its extreme structure as a substitute for social skills. If you are Luke Skywalker and she is Princess Leia, you already know what to say to each other, which is so much safer than having to ad-lib it. Your fannish obsession is your beard. If you know absolutely all the trivia about your cubbyhole of pop culture, it saves you from having to know anything about anything else. That’s why it’s excruciatingly boring to talk to such people: They’re always asking you questions they know the answer to.

Ouch! At the time many people thought this was a tad too mean-spirited towards these hardcore fans but considering that entire subcultures have since formed around gatekeeping and complaining about new installments in popular franchises, I do think Ebert might’ve had a very good point in saying that fandom isn’t a substitute for having a personality. The amount of outrage I see over filmmakers taking some creative liberties when it comes to the pre-existing lore of a franchise or worse endless videos whining about casting (particularly those involving women and people of color) is baffling.

Look, I am also a fan of certain films and franchises that haven’t had great Hollywood adaptations/remakes. For instance, I absolutely love ”Cowboy Bebop” and ”Ghost in the Shell” both of which had lackluster Hollywood adaptations. I gave them a chance, decided it wasn’t for me, and then moved on with my life. I didn’t get irrationally angry at the films or their creators. What’s even worse is that fans seem to hold a vendetta against filmmakers who in their view have “sullied” their favorite franchise. I haven’t seen ”The Last Jedi” but I know its entire plot because there would be endless debates about it in discussions leading up to the release of Rian Johnsons’s ”Knives Out.” In my view, this level of obsession with any film, comic, or book is quite frankly unhealthy and Ebert seems vindicated in his assessment of hardcore fanboys.

Also Related: The 15 Best A24 Comedy Movies

Peter Nicholls, The Thing (1982) Review

John Carpenter’s “The Thing” (1982) is one of the most famous examples of a film that was negatively received during its release only to become a beloved classic later. It wasn’t even a mixed reception, “The Thing” was nearly universally reviled by the critics and audiences at the time. According to John Carpenter, the film was pilloried even by science fiction fans.

I take every failure hard. The one I took the hardest was The Thing. My career would have been different if that had been a big hit … The movie was hated. Even by science-fiction fans. They thought that I had betrayed some kind of trust, and the piling on was insane. Even the original movie’s director, Christian Nyby, was dissing me.

Now that is heartbreaking to read. One of the earliest voices to champion “The Thing” was the prominent Australian critic Peter Nicholls. His brief review from 1992 not only touches on all the qualities that make the film great but also presciently remarks that it would likely go on to become a classic.

There is a case for arguing that the Carpenter version goes as far as genre movies normally dare, if not further, in questioning not just the nature of humanity under stress but its value. Faced by the alien, the humans themselves become inhuman in every possible way. It is a black, memorable film, and may yet be seen as a classic. The novelization is The Thing (1982) by Alan Dean Foster.

And boy, was he right. Today, “The Thing” is considered an all-time classic of horror cinema, and it is because of voices like Peter Nicholls, who chose to go against the grain, that the film was able to reach that status.

Also Read: 10 Best John Carpenter Movies

Mr.Plinkett, Star Trek (2009) Review

In fact, J.J. Abrams should have directed the prequels and George Lucas should have directed people to their seats in the theater.

Speaking of fanboys, let’s talk about this review from people who are more into geek culture. Obviously, the above quote hasn’t aged well and RedLetterMedia, later on, justified this statement by saying they only wanted J.J. Abrams to direct but not write. I have to say I find that to be a tad dishonest. Moreover, I say this because throughout this review they justify aspects of ”Star Trek” (2009) that would go on to become the point of criticism in ”The Force Awakens.”

I am referring to the parts where they basically defend “Star Trek” (2009) for being nothing more than an exercise on nostalgia with some added action, arguing that the more interesting sci-fi/philosophical elements of “Star Trek” wouldn’t have made for an exciting action movie and no studio would spend hundreds of millions for anything more complicated. Not only that they also use this excuse the movie for having a weak villain because the movie has to spend time reintroducing the iconic characters and lore to a wider audience.

Look, I always appreciate critics who keep in mind the limitations a filmmaker has to face when handling films whose budget is north of 100 million. It obviously can’t be like an experimental art film but that doesn’t mean it can’t have interesting ideas. See it’s one thing to defend a filmmaker creating a film that makes interesting ideas palatable and even entertaining to a wider audience and another thing to argue “This film is a soulless cash grab because the audience is dumb, so just enjoy this action.”

There have always been filmmakers who have the audience in mind when making a film like Hitchcock, Spielberg, Cameron, and Chris Nolan but they did it without making their films as generic as possible. Also, to be clear, I am not arguing that you can’t enjoy these movies as simplistic action movies but there’s nothing to suggest that they can’t aspire to be something more. Another fascinating thing about their reviews for these franchise films (I also listened to their “Force Awakens” review) is the amount of importance they give to the lore. Lore is no longer something that’s supposed to supplement the story and themes but rather something that should be the primary focus of the filmmakers where they’re expected to build stories that revolve around and make use of this pre-existing lore.

They also dedicate a portion of these reviews to writing fanfiction about what these filmmakers could’ve done with these characters and lore instead of what the filmmakers actually did. Of course, we all saw what such an approach can lead to with the sequel trilogy basically imploding in on itself. I know there are film series that have succeeded despite there being not much of a plan initially (the original “Star Wars” trilogy itself being a great example of this) but it’s hard to succeed when your foundation is as shallow as TFA. Anyway, I didn’t find these reviews to be particularly insightful about the movies themselves (no offense to their fans) but they do give some insight into what fanboys of franchises basically expect from filmmakers.

Related to Star Trek: 30 Best Sci-Fi Movies of the 21st Century

Bosley Crowther, Bonnie and Clyde (1967) Review

It’s well known that at the time of its release, ”Bonnie and Clyde” inspired polarizing reactions among critics. Some like Pauline Kael and Roger Ebert gave it rave reviews calling it a milestone in American cinema while others like Bosley Crowther savaged it, calling it a sleazy film that glorified violence. Eventually, it was Pauline Kael and her essays that won out and the narrative changed in the film’s favor. Joe Morgenstern changed his view of the film after a second viewing while it’s speculated that Bosley Crowther lost his position in The New York Times because he was believed to be out of touch with public opinion. Still, if you read Bosley Crowther’s review one realizes things haven’t changed that much regarding the discourse around violence in film. From his review.

A raw and unmitigated campaign of sheer press agentry has been trying to put across the notion that Warner Brothers’ Bonnie and Clyde is a faithful representation of the desperado careers of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, a notorious team of bank robbers and killers who roamed Texas and Oklahoma in the post-Depression years.

It is nothing of the sort. It is a cheap piece of bald-faced slapstick comedy that treats the hideous depredations of that sleazy, moronic pair as though they were as full of fun and frolic as the jazz-age cutups in Thoroughly Modern Millie. And it puts forth Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway in the leading roles, and Michael J. Pollard as their sidekick, a simpering, nose-picking rube, as though they were striving mightily to be the Beverly Hillbillies of next year.

How often have we seen similar sentiments expressed towards films that came long after “Bonnie and Clyde”? Films like ”A Clockwork Orange,” ”Fight Club,” and ”Watchmen” have received similar responses. In fact, Roger Ebert who praised “Bonnie and Clyde” and considers Kael to be a major influence had this to say about Fight Club.

“Fight Club” is the most frankly and cheerfully fascist big-star movie since “Death Wish,” a celebration of violence in which the heroes write themselves a license to drink, smoke, screw and beat one another up. Sometimes, for variety, they beat up themselves. It’s macho porn — the sex movie Hollywood has been moving toward for years, in which eroticism between the sexes is replaced by all-guy locker-room fights.

and

Of course, “Fight Club” itself does not advocate Durden’s philosophy. It is a warning against it, I guess; one critic I like says it makes “a telling point about the bestial nature of man and what can happen when the numbing effects of day-to-day drudgery cause people to go a little crazy.” I think it’s the numbing effects of movies like this that cause people to go a little crazy. Although sophisticates will be able to rationalize the movie as an argument against the behavior it shows, my guess is that the audience will like the behavior but not the argument. Certainly, they’ll buy tickets because they can see Pitt and Norton pounding on each other; a lot more people will leave this movie and get in fights than will leave it discussing Tyler Durden’s moral philosophy. The images in movies like this argue for themselves, and it takes a lot of narration (or Narration) to argue against them.

Is there a way to portray violence without glorifying it even a little? I guess the debate around that will continue for a long time.

Read More: 100 Years of Pauline Kael

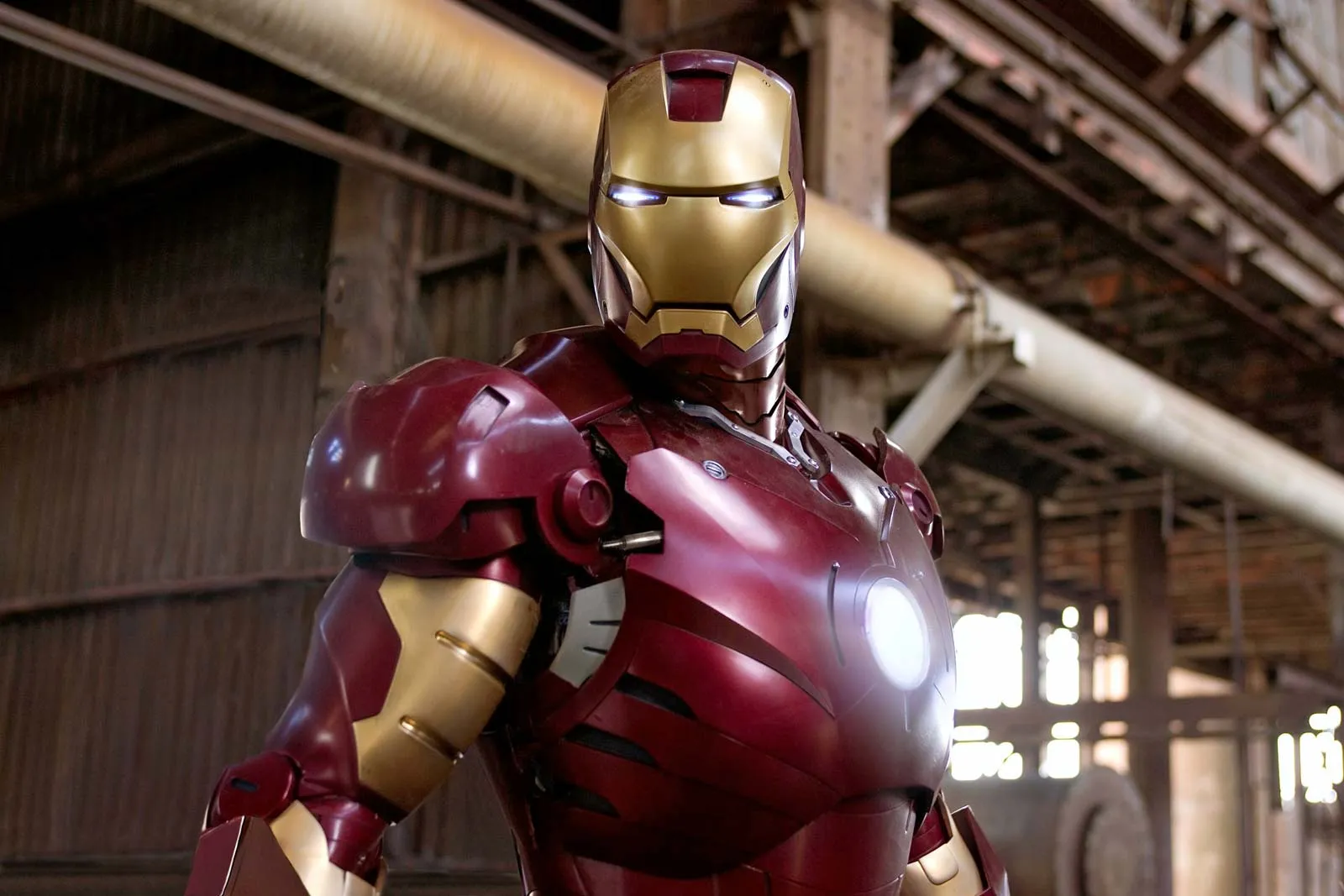

Roger Ebert, Iron Man (2008) Review

“Iron Man” – the movie that kick-started the most financially successful film franchise in history. While it’s common these days to see the MCU criticized for being too formulaic, we tend to forget that when Robert Downey Jr. donned Iron Man suit in 2008 it was considered a breath of fresh air compared to other superhero films. With that in mind, Roger Ebert’s review of “Iron Man” feels oddly prophetic in how it foreshadows what the MCU would turn out to be in the future.

It’s prudent, I think, that Favreau positions the rest of the characters in a more serious vein. The supporting cast wisely does not try to one-up him. Gwyneth Paltrow plays Pepper Potts as a woman who is seriously concerned that this goofball will kill himself. Jeff Bridges makes Obadiah Stane one of the great superhero villains by seeming plausibly concerned about the stock price. Terrence Howard, as Col. Rhodes, is at every moment a conventional straight arrow. What a horror show it would have been if they were all tuned to Tony Stark’s sardonic wavelength. We’d be back in the world of “Swingers” (1996) which was written by Favreau.

Another of the film’s novelties is that the enemy is not a conspiracy or spy organization. It is instead the reality in our own world today: Armaments are escalating beyond the ability to control them. In most movies in this genre, the goal would be to create bigger and better weapons. How unique that Tony Stark wants to disarm. It makes him a superhero who can think, reason and draw moral conclusions, instead of one who recites platitudes.

To me, it feels unreal reading some of those sentences in 2024. In the decade after that review was written, the MCU would turn every single one of their characters into Quipbot9000, and Tony Stark would go on to make bigger and better weapons (Ultron, Spidey’s armor), giving them even to teenagers. It also shows why Tony’s flippant nature in “Iron Man” worked so well. He was so endearing because, as Ebert astutely points out, we can sense that his persona is, in part, an attempt to hide deep, private wounds, and positioning the other characters in a more serious vein creates a great dynamic. When everyone becomes comedic with no rhyme or reason, it isn’t as compelling, especially when said humor is often used to undercut serious emotional moments which is so often the case with these Marvel films.

Overall, this review gives us a better understanding and appreciation of what made a great movie work so well and also provides insight into what its imitators are doing wrong. It’s reviews like this that make reading Roger Ebert so much fun, even more so than his famous takedowns of bad films.

Related to Iron Man: Who is Tony Stark?

C. A. Lejeune, Psycho (1960) Review

Today, we take it for granted that Hitchcock is considered one of the towering icons of cinema, and it’s hard to wrap your head around the idea that he wasn’t always viewed as a visionary genius throughout his career. Indeed, at one point, a section of critics considered him merely a competent director of thrillers and hotly contested the idea that he was a great artist. As film historian Simon Hitchman notes in his blog, it was French critics, particularly the Cahiers group, who began to challenge this view.

But then, in the early 1950s, Hitchcock found himself and his work unexpectedly lionized in the pages of specialist film magazines and journals in France. In publications such as Le Revue du Cinéma, La Gazette du Cinéma, and most famously, Cahiers du Cinéma, a new generation of passionate cinephiles were writing about cinema with an unusual intensity and intellectual depth. Favoring the style of a film over its content, these cine-literate young critics – among them Maurice Scherer (Eric Rohmer), Jacques Rivette, Claude Chabrol, Jean-Luc Godard, and Francois Truffaut – contradicted the then orthodox view of European cinema as representing art and American cinema as mass entertainment. They argued that some of the most important contemporary directors, not least Alfred Hitchcock, were working within the Hollywood studio system. Hitchcock was, for them, the supreme example of what they called an “auteur”, or a director whose mastery of mise-en-scene and thematic consistency made them the true “authors” of their films.

Many of Hitchcock’s classics were often met with mixed critical reception, including his most iconic film, “Psycho” (1960), which many critics dismissed as sensationalistic and exploitative. One of the more extreme reactions came from The Observer critic and longtime friend of Hitchcock, C. A. Lejeune. By that point, Lejeune was already becoming disillusioned with various emerging trends in film, and she was so appalled by “Psycho” that she walked out before it ended and, shortly after, resigned from her role as film critic at The Observer. She was also not impressed by the marketing surrounding the film.

The stupid air of mystery and portent surrounding Psycho’s presentation strikes me as a tremendous error. “The manager of this theatre has been instructed, at the risk of his life, not to admit any persons after the picture starts.” “By the way, after you see Psycho don’t give away the ending.” Signed, Alfred Hitchcock. I couldn’t give away the ending if I wanted to, for the simple reason that I grew so sick and tired of the whole beastly business that I didn’t stop to see it. Your edict may keep me out of the theatre, my dear Hitchcock, but I’m hanged if it will keep me in.

Lejeune’s dramatic exit from “Psycho” was a parting shot from an era unwilling to confront the darker turns of cinema. Hitchcock’s thriller might have repelled her, but it captured audiences—and critics—who would later hail it as a revolutionary work that redefined horror and suspense.

Also Read: Dial ‘M’ for Masterpiece: 20 Best Movies of Alfred Hitchcock, Ranked

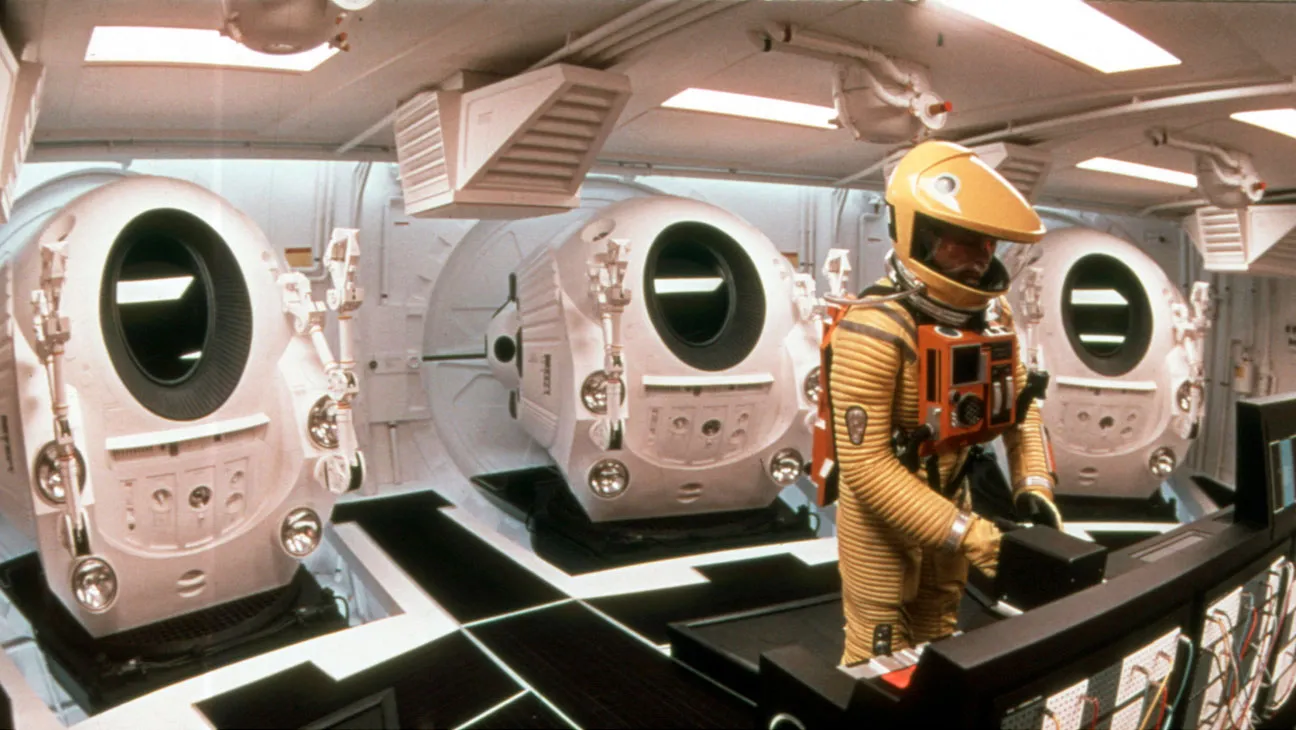

Pauline Kael, 2001 A Space Odyssey (1968)

Pauline Kael’s famously negative review of “2001: A Space Odyssey” illustrates her iconoclastic, sometimes contrarian approach to film criticism. Kael wasn’t one to shy away from criticizing beloved films, and “2001” was just one of many classics she derided. Her biting reviews also targeted films like “La Dolce Vita,” “Badlands,” “Dr. Strangelove,” “Wild Strawberries,” “Red Desert,” “Faces,” “Blow-Up,” and “A Clockwork Orange.”

However, her review of “2001” is infamous because her reasons for disliking the film are so far removed from what the film is known for that it feels downright bizarre reading her review today. For instance, she called “2001” “commercial,” a term that feels almost surreal considering the film’s slow pacing, minimalist dialogue, and abstract storytelling—features that starkly contrast with what we consider commercial today.

Adding to this, she called the film “monumentally unimaginative” and if there’s one thing that people agree about “2001” today, it’s that it had a lot of imagination. In fact, one of the common praises you’ll often hear from fresh viewers of “2001” is how it feels like a modern hard sci-fi film in terms of its portrayal of space-faring technology. To top it all off, she accuses the film of glorifying weapons when in reality the film is mostly likely not making any statement about tools of death, from Wikipedia.

In a book he wrote with Kubrick’s assistance, Alexander Walker states that Kubrick eventually decided that nuclear weapons had “no place at all in the film’s thematic development”, being an “orbiting red herring” that would “merely have raised irrelevant questions to suggest this as a reality of the twenty-first century”

Even if we were to assume that it is about weapons, the consensus is that there’s little in the film to support the thesis that the film is glorifying them. Kael’s critique of “2001” remains one of the boldest examples of her tendency to challenge conventional wisdom, even when it seemed to defy the essence of the film itself. Her review has become a fascinating counterpoint in the film’s legacy, a reminder of how deeply personal—and divisive—the interpretation of cinema can be.