How ‘Mysterious Skin’ Succeeds in Portraying Abuse Stories: Trauma seen through the lens of abused men is hardly shown in cinema, and if also queer-centered, it often ends up underdeveloped or built on the exploitation of pain. Abuse portrayal, in general, is probably one of the most complicated subjects to depict. And if it covers an uncommon reality, it could risk falling victim to stereotypes and clichés. But trauma is not only suffering and violent scenes. It’s a life-altering experience that feeds off your soul, not easy to be told by or for someone who hasn’t experienced it. It’s something that sticks with you. However, at the same time, it’s not a helpless condition, as life is not to be limited by the past. There’s more to life, and some narratives can be helpful to process and understand this.

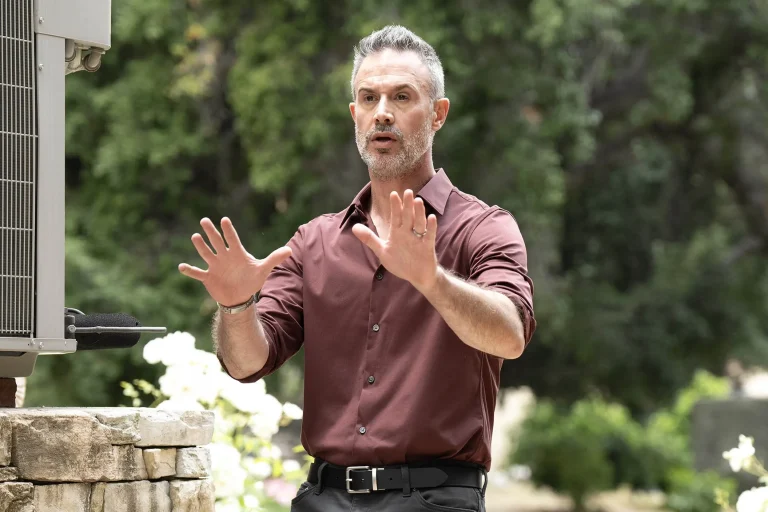

Adapted from Scott Heim’s novel of the same name, Mysterious Skin is a 2004 movie written and directed by Gregg Araki. Probably the director’s most notorious work, the film has received acclaim for the way it portrays the consequences of child abuse on men. On the other hand, Araki’s narration has also been considered scandalous for the unconventionally direct and realistic depiction of such a traumatizing reality.

The film follows the intertwined story of two young Kansas boys, Neil McCormick (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) and Brian Lackey (Brady Corbet). They reconnect ten years later due to a life-altering event that occurred to them as children during the summer. Both of them struggled with neglectful parents: Neil is the son of a single mother who prioritized her fleeting relationships, while Brian’s father is equally forgetful of his parental duties. Eventually, none of the two realize the abuse at the time, resulting in the inability to give comfort to their sons.

However, the event has been causing now-18-year-old Brian to have frequent nosebleeds, wet bedding, and vivid nightmares. There, he is being touched by a blush and a strange hand. “When I was eight years old, five hours disappeared from my life,” Brian narrates, stating that he believes he’s a victim of alien abduction and looks for answers, hoping to find some inner peace. “It started to rain. What happened after remains a pitch-black void”, he continues. As he tries to untangle the mystery behind his nightmares, he finds a picture of his Little League team. The photo shows a young Neil, who Brian remembers to have been with him during the supposed abduction. Due to this revelation, he immediately tries to track his former baseball team buddy.

Confused and distressed by this mysterious childhood event, he has become an obsessive, anxious, and timid boy unable to make friends. Meanwhile, the tragic event has shaped Neil into someone completely different from the scared and distraught Brian. With time, Neil has grown up to be a disenchanted sex worker since the age of 15, and he vividly remembers that summer memory. While showing his side of the story, his words bitterly revive the accident: “It just happened, that’s what I told myself.” Remembering more clearly the harshness of what happened to them, he has a more hopeless and destructive attitude towards life. His best friend Wendy (Michelle Trachtenberg) believes that “where people have a heart, Neil McCormick has a bottomless black hole.” But just like Brian, he has trouble facing his trauma, although in a different facet.

Intricate and gripping, this narration works as a framing device. Throughout the two main character’s perspectives, it’s revealed that Neil and Brian’s baseball coach abused them during the same night. Neil was the coach’s “favorite,” a role that convinced him that the abuse experienced was love. Openly queer, he later develops a strange attraction to older men and unsafely leads his sex life. Unsurprisingly, in the real Gregg Araki style, the queer representation is realistic and thoughtful.

Most stories about child abuse might show homosexuality as a “hypersexual reaction” to the tragic event, while Neil’s homosexuality has naturally no connection to his trauma. He is his own person. For Brian, on the other hand, hypersexuality does not become a coping mechanism. Instead, he rejects any kind of sexual offer or physical touch. At one point, he starts to cherish his time with Avalyn (Mary Lynn Rajskub), a girl he discovered on TV, as she’s convinced of being abducted, too. Once the girl tries a sex probe on him, he scarily pushes her away and tells her to go, ending it once and for all.

In some way, Neil obsesses, similarly to Brian, over the abuse. The only difference is that he’s aware of what happened, but he’s convinced that was his true love, a relationship he’ll never experience again. As he recounts: “But what happened that summer…is a huge part of me. No one ever made me feel that way, before or ever since.” Neil keeps cassettes, pictures, and objects to keep the memory alive, treating it like a love treasure. He comes back to the coach’s house more than once, mad at him for abandoning him right after the abuse.

As the story progresses, we experience what’s similar to a puzzle game, where each scene helps the audience – and, eventually, the characters – to put the different pieces together, showing the whole picture of the incident. When playing a puzzle, one connects the same pieces according to a different and personal order. Just like that, the abuse is shown piece by piece, perfectly portraying the diverse way one comes to terms with their traumatic experiences. No one lives them the same way, and there’s no singular and homogenous solution to overcome what the final image provokes. There’s probably no way to, but the image is there; it’s inescapable.

But once we get close to someone, things might be for the better. Beyond Neil and Wendy’s soulmate-like friendship, Neil and Brian have Eric’s (Jeffrey Licon) full support. Connecting with others plays an important part. Thanks to Eric, Brian finally has a friend and acts more carefreely. After an encounter with a client with AIDS who just wants his back rubbed, Neil also realizes that he must get off the dangerous path his life has taken. The man tells Neil: “Really, I just need to be touched,” and his whole world changes.

Before his return to Kansas for Christmas, Neil ends up being abused again on a last sex work shift. This latest traumatic experience represents some sort of reality check for him, due to which he realizes that the nature of his past and the life path he’s been on will get him back on a harrowing abusive cycle. Once back home, Neil and Brian finally meet again. He takes him back to the place of his nightmares: there’s an epiphany. They slowly start remembering about each other, and Brian, bit by bit, figures out what happened that summer night. He begs Neil to tell him everything, to which he agrees and answers with as much detail as possible.

Trembling, Brian gets on his lap, looking for comfort, nearly resembling his little boy self. He eventually breaks down, bursting into tears while bleeding from his nose. Still shaking, Neil comforts him, and while they hold each other, Carolers appear outside the house door, singing Holy Night. Recalling the tenderness of a fable, they face their past bitterly. But with a taste of hope, Neil’s thoughts share an eagerness to go on:

“And I thought of all the grief and sadness and fucked up suffering in the world, and it made me want to escape. I wished with all my heart that we could just leave this world behind. Rise like two angels in the night and magically disappear.”

Almost every narrative sequence resembles a fever dream, shaping Brian’s perpetual surreal and confused state. It cuts off to rougher imagery, depicting Neil’s frail and self-destructive lifestyle. The movie’s artistry is exceptional, as it takes care of its characters while maintaining an appropriate distance, giving them the space and time to develop. Like a friend, it offers enough support to work on themselves and convince them that everything will be alright. And at the same time, it does not compromise their freedom and tries to achieve closure on their own terms.

What differentiates the film from other portrayals of abuse is that, here, the abuser is not at the center of the narration. It’s not about how disgusting he is but about how his actions affected the victims and how they tried to heal their wounds. For once, they’re deservedly the eyes through which we see the story, and we should focus on their point of view, not through non-stop images of cruelty.

Mysterious Skin doesn’t sugarcoat the consequences and despicable nature of child abuse but, at the same time, doesn’t feed on suffering. Despite the scandalous nature of its narrative, the film shows thoughtful sensibility and understanding. The shock value is an aftermath; it derives from our inability to face the world’s harshness and chaos. In fact, there’s no desire to shock the viewers but to connect with them through these harrowing events, showing through Neil and Brian’s reencounter that there’s hope and beauty in the world for us not to give up despite everything.