Into the fifties, a trinity of electric young performers—Montgomery Clift, Marlon Brando and James Dean, in that order—emerged as major players in the movie industry. All students trained in The Actors’ Studio, the trio greatly popularized Method Acting. Not what we have come to know today of going extreme, sometimes wild, lengths for immersing into a role, but truthfully, it means exploring and exteriorizing the inner complexity of the human condition by way of your own personal experience.

This introduced a new type of leading man, who, unlike its precursors—the dashing and suave casanovas of Gary Cooper and Errol Flynn; the dorky and sweet charmers of Cary Grant and Jimmy Stewart; or the cynical and unbeatable tough guys of John Wayne and Humphrey Bogart—showcased a deeply nuanced and conflicted emotional spectrum, offering more wounded and vulnerable representations of masculinity on screen. Their protagonists could cry just as easily as they could brawl, show hesitance and apprehension in the same breath as courage and chivalry. They weren’t men so much as they were human.

For today’s standards, the manhood with soft edges of their characters may seem natural, moreover, expected. But, at the time, it was something totally unheard of. This shift prevailed, especially into the seventies, when the shabby look and atypical personalities came into vogue through the likes of another triad of giants: Dustin Hoffman, Al Pacino and Robert De Niro, that funnily enough, were the ones who pushed and converted ‘The Method’, so to speak, into the idea of living the part as opposed to just playing it.

However, after a period of gloomy and gritty realism, escapism became vital once again, and the action genre dominated the marquees throughout the eighties. This brought with it some old-fashioned ideals of manliness back into the public imagination, featuring hypermasculine and impossibly chiseled physiques by the likes of Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone and Jean-Claude Van Damme. Enter “Point Break” (1991) directed by the eclectic Kathryn Bigelow.

It is no secret that Bigelow has a proclivity for stories framed through film genres typically associated with men, both in front and behind the camera—bombastic, adrenaline-fueled, action-driven spectacles. And while it may be sexist, to some degree or another, to assert she possesses an inherent female gaze, the thematic subversions of her often overlooked but consistently brilliant oeuvre is indicative of a sensibility her male counterparts lack altogether, presumably and precisely because of their gender.

Operating within frameworks that directly rely on heavy doses of testosterone to come to life, may suggest that Bigelow, a woman herself, has a biological deficiency going against her, if not for the fact she has delivered some of the most invigorating films in the American landscape of movies. And, in fact, there may not be a greater indication of her contrapuntal genius than her initially dismissed but since reassessed film “Point Break.”

Set against the sun-baked Californian coast, this highly unusual police procedural follows a slim Keanu Reeves, long before he became a bona fide action star, as Johnny Utah, an overachieving rookie assigned to the FBI Los Angeles division. Over there, he must join forces with a jaded officer by the name of Papas (Gary Busey), and investigate a series of robberies committed by an unidentified group of criminals that call themselves ‘The Ex-Presidents’—for each member wears a rubber mask of Reagan, Nixon, Lyndon and Carter.

The highly skilled criminals have successfully perpetrated a series of heists and evaded the authorities without any difficulty. And the only theory, backed by Papas, sounds way too ridiculous to ever be taken seriously by anyone at the Bureau. Of course, the novice believes in the wisdom of his elder and falls for this idea. And just like that—in the iconic words of Barbie’s boy toy accessory, Ryan Gosling´s human-sized doll Ken—his office job quite literally becomes ‘Just Beach’.

His mission is to discreetly infiltrate the free-spirited Surf Culture and discover the identities of the robbers hiding underneath the guise of American democracy. Johnny’s first attempt at surfing goes as embarrassingly bad as Ken crashing headfirst into the plastic ocean of Barbieland, except Johnny does not fly backwards into the air, but plunges into the turbulent waters. Pro surfer, Tyler, comes and saves him from dying before he has started living. This accident makes Johnny realize two important things: first, that mastering the art of riding waves is not an easy one, and second, surfing ain’t merely a hobby, but a whole way of living. So if he intends to blend seamlessly into the salty-haired, tan-skinned beach bums, he must surrender completely to the groovy lifestyle.

To achieve this, he’ll need a mentor, and who could be better for the task than the striking woman that rescued him. Under her wing, he gets to learn the basics and mechanics of surfing. Before venturing into the water, she teaches him on steady land ‘The Pop-Up’, as they call it. This is a fundamental technique that involves transitioning swiftly from a prone position on your board to an upright stance. Then comes paddling, necessary to get yourself near the waves you wish to ride and, last but not least, wave reading, as in understanding the water’s behavior. Bigelow films these lessons with the simmering sensuality of a sex scene, as if the flirtation and love-making between Johnny and Tyler was not with one another, but with the ocean itself.

They are not the only ones enamoured with the gentle caressing of the salty breeze and rough janking of the crashing waves. Amongst the many riders of the sea, one stands out. This is Bodhi, a statuesque and dexterous Patrick Swayze, who serves as the radical yang to Johnny’s yin. Blonde’s are said to have more fun [than brunettes], in which case, to quote another complementary male duo, Bodhi is all the ways Johnny wishes he could be: he looks like he would want to look, fucks like he would want to fuck… is smart, capable, and, most importantly, is free in all the ways he is not. So it is only natural that Johnny feels attracted to Bodhi, not on a sexual level, but a deeply spiritual one. Soon, what began as a professional assignment turns into a personal journey of self-discovery.

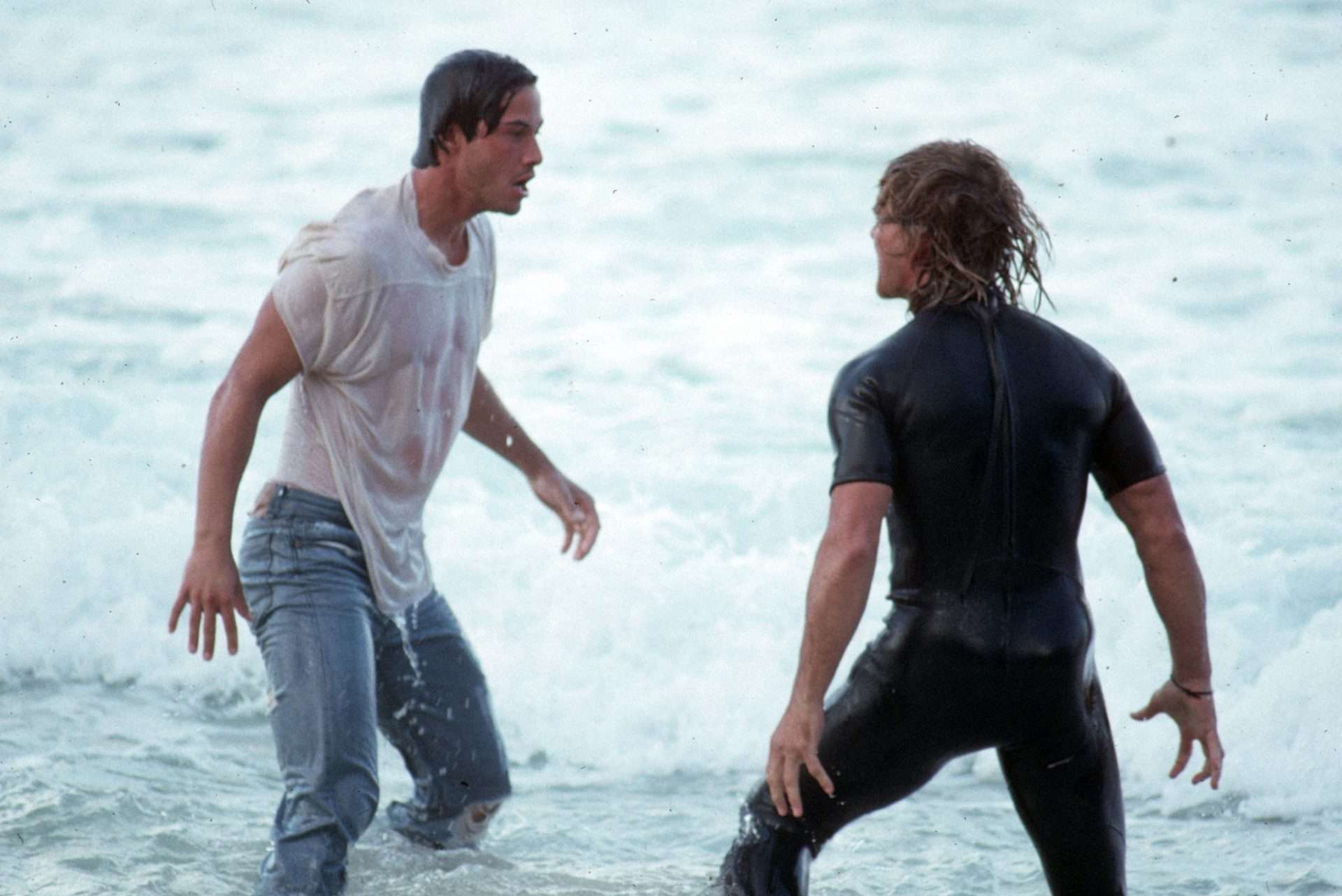

Once Johnny surfs on his own, without the guarding of Tyler, he throws himself into the water without a proper knowledge of a Surfer’s Code and Etiquette, which includes being aware of surroundings not to endanger fellow surfers. So he cluelessly dives into somebody else’s wave, crashing into the man and bumping him off his surfboard. Known for being territorial, not long after their quarrel, the man and his pals look after Johnny to beat him up, which they do until Bodhi intervenes and kicks their tanned asses. This incident leads Johnny to believe these guys are the ones behind the heists, especially since, after digging up their information, he discovers they’re involved in illegal stuff. Which then culminates in a deadly raid.

Charmed by the spell of Bodhi, Johnny fails to realize sooner that his new adrenaline-junkie friends were the target of his operative all along, and by the time he does, he has grown too fond of them to stop their mischief, especially since he knows their motive isn’t harming others, but instead, a means to fund their anti-establishment way of living, which he too has fallen in love with. In his defense, agent Utah is far from being the only undercover operative [in film] to be seduced and swayed by the double life he leads. Though that doesn’t make it less of a glaring mistake against his better judgement.

Not since Tony Scott’s “Top Gun” (1986) had a masculine movie been so overtly homoerotic. But while Scott’s sweaty treatment seems oblivious of its inclinations, Bigelow not only recognizes it, she intelligently deploys all of the sexual tension to create heart-pounding climaxes of action—an exhausting chase scene, a botched bank heist, and before Cruise did it, a balletic skydive sequence. Her direction extrapolates the debilitating rush of sex and applies it to violence. Thirty-four years later, it is clear that for “Point Break,” Bigelow wasn’t interested in fleeting thrills, but instead, everlasting sensations.

![Outlier [2021] Review: Psychological thriller about abuse drags to a finish](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Outlier-1-768x320.jpg)

![The Cordillera of Dreams [2019]: ‘KVIFF’ Review – A Piercingly Elegiac Documentary on Landscape and Memory](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/The-Cordillera-of-Dreams-Doc-768x401.jpg)