If you had asked me a couple of years back which import of American network television I imagined being used as a template for multiple adaptations and remakes, the Ann Bidermann-created seven-season Showtime drama “Ray Donovan” wouldn’t have been anywhere near the vicinity of that imagination. That could be accounted for by the show’s general mediocrity of quality, which coasted primarily on the performances of the central cast and a killer premise that can generate storylines for multiple seasons, but not necessarily compelling ones.

If examined further, the central issue of the source, which is also being extended to its official remake, “Rana Naidu,” is in its evocation of “The Sopranos” ethos—the professional world against the personal dilemma. “Ray Donovan,” and to that end Rana Naidu’s first season’s misstep, is in its expectation that its personal subplots are similar or more compelling than the central plot thread, when in reality the stacking of cliches upon cliches threatened to decrease the thematic potency of the frayed relationship between fathers and sons, or the cyclical nature of the sins of the fathers doomed to be repeated by their offspring. I can report, though not happily, that many of the same problems extend to the second season of “Rana Naidu” as well.

Thus, what remains within the fading lapses of memory (caused by the seasons releasing within a span of three years) is the flowery, intricate cursing by Venkatesh’s Naga Naidu, or the highly stylised action, with dollops of both sex and gore. It reminded you of a five-year-old having first learned of an adult rating and trying to write a “mature” tale sans the maturity, choked with edginess. There is fun to be had within that sloppily dripping pulp, and the sheer wordsmith that had been Suparn S. Verma’s dialogues, aided by a gleeful energy within showrunner Karan Anshuman.

I do think the news outlets reporting the hue and cry from the Telugu states due to Venkatesh’s liberal cursing, a far cry from his usual image of a family-friendly mass hero, was one of, if not a major contributor to the flattening of the edginess. While Naga still retains that impish unpredictability, his general sliminess is traded in for comic relief and moments of emotional poignancy. Even after sanding off the edges of the character, Venkatesh is in fine form, easily the best out of a very stacked central cast.

The supporting cast, Sushant Singh and Abhishek Banerjee, both deliver in spades. Unlike the first season, where the subplots of the Naidu brothers seemed ancillary and barely integrated unless necessary, season 2 of “Rana Naidu” manages to incorporate those subplots far better into the main narrative. Similar praise should be afforded to the subplots of both kids. Young Ani would be kidnapped in the opening of the second season, forced to watch his father burn a man alive to rescue him. His elder sister, on the other hand, would be far more of a necessary ingredient in the impending war between Rana Naidu and Mumbai-based gangster Rauf Mirza (Arjun Rampal), and that brings forth an increase in stakes within the narrative itself.

But sans Rampal, who is having a ball hamming it up with his charisma and unpredictability as Rauf, the rest of the newer additions within the cast are emblematic of the problems that “Rana Naidu” season 2 depicts. The addition of Rajat Kapoor as rich businessman Viraj Oberoi lacks any major impact—a similar effect is extended to Kriti Kharbanda’s portrayal of Alia Oberoi, daughter of Viraj, or Tanuj Virwani’s portrayal of the wayward, spoiled son.

Most of their scenes comprise two siblings battling it out for their father’s approval, with the plot mechanics—Alia’s attempts to buy a franchise cricket team or Viraj’s movie studio creaking under the weight of major flops—barely serve as window dressing in the show’s attempts at commentary on capitalism and the perils of fantasy cricket. It’s a plot thread that struggles to register, which is all the more noticeable because of the driving force of motivation for Rana’s actions to do “one last job.”

This thus circles back to the stacking of cliches upon cliches, and poor Surveen Chawla as the disappointed wife who dips her toes in an affair seemed far more of an add-on to the already innumerable cliches. The pleasures to be had are in the immediate payoffs of these moments—a confrontation between Rana and Naveen (Dino Morea) at a police station or Rauf implicitly threatening Rana’s daughter as they are discreetly exiting the police station. Characters like Chawla’s Naina, Aditi Shetty’s Tasneem, or even Kriti Kharbanda’s Alia are welcome additions of female characters being given space to shine.

I do have to address the events surrounding Tasneem’s introduction in the second episode of the series, which had been constructed with a comedic premise, but only paints Banerjee’s Tej Naidu as creepy. Though Shetty later within the series has moments to fill her character with enough personality, such that one could root for both Tasneem and Tej.

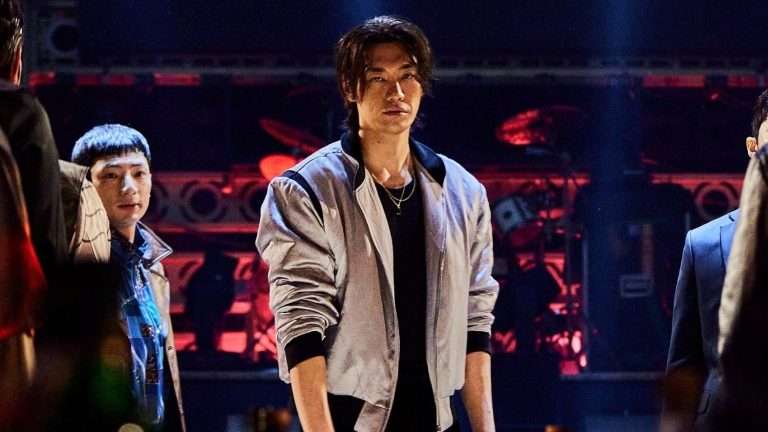

I say “moments” because even as the show displays a modicum of greater depth than its previous season, it never lifts itself from the morass of mediocrity. The edgy provocativeness is gone, replaced instead by familiar plot mechanics and cliches. It is, however, cut far too rapidly, especially towards the tail end of the season, to fruitfully register. Action sequences have been developed with ambition and even stylization, but the haywire editing hinders them. Rana Dagubatti as Rana Naidu is sturdy and reliably stoic as the lead, and the show itself remains watchable. It trades away the sheer baffling hilarity of the dialogues and the edginess of the first season for sprinkles of depth and poignancy, but ultimately blandly made, somewhat competent fare.

I am confused about whether that’s levelling up or sinking deeper into the morass of forgettability. Then again, this confusion is far more impactful a response than sheer forgetfulness of the source material, so Karan Anshuman’s adaptation is a winner on that front.