There are realities they do not want to show… They create them, but do not want to show them?

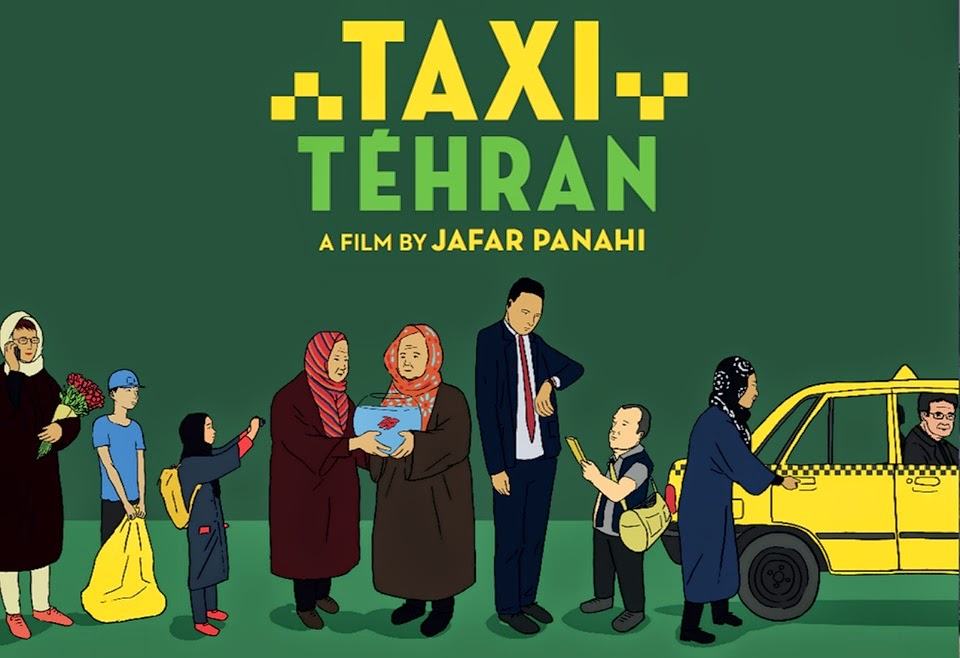

“Taxi” aka “Taxi Tehran” (2015) is the third minimalist exercise by Iranian film-maker Jafar Panahi, who was sentenced to a 20 year film-making ban by the Iranian government (back in 2010). And like his two previous films, “Taxi” isn’t just a proclamation of Panahi’s boldness and defiance; it is also a nicely coiled allegory and a biting satire on the limitations imposed on him as well as on many fellow Iranians. While “This is Not a Film” (2011) was diffused with an atmosphere of despair and “Closed Curtain” (2013) laced with righteous anger, “Taxi” is enlivened with bursts of optimism and sarcasm (Panahi even smiles a lot in the film).

The film has a very simple conceit. Director Panahi, who was set free from house arrest, ventures around the streets of Tehran posing as a taxi driver with cameras atop dash-cam & rear-view mirror (a similar kind of set-up was used by Abbas Kiarostami in “Ten” (2002)). He seems to pick up random people and record their views, which includes view on capital punishment to making films in Iran. Yes of course, this is a faux-documentary style that has been predominantly used to death in contemporary movies. Like all self-conscious Iranian film-makers, Panahi even allows one character to figure out the anomaly “They were actors, right Mr. Panahi? You thought you could fool me?” (even though this character isn’t even present, while the previous conversation happens). Each and every unrelated vignette that unfolds inside the confines of taxi keeps on subtly hitting at the prevalent societal oppression.

Abbas Kiarostami and Jafar Panahi are known for their trademark factor to blend in reality and fiction. “Taxi” also has many such moments, where many of the characters who walk into the Panahi’s camera are a blend of his reality and cinematic imagination. A pirated CD’s seller defends his livelihood (one who is said to supply for Panahi) on how he immensely helps the film students studying the state-run syllabus; A bright, fast-talking little girl (said to be Panahi’s niece) beautifully displays all the defects with the rules imposed to make films in Iran; a bloodied victim of a motorcycle accident lying on the lap of his wailing wife, asks the driver’s mobile to record his last will which is to bequeath all the properties to the wife (since government defaults all possessions only to the closest male relative); a disbarred lawyer distributes flowers with a smile (in fact, she is the world-renowned human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh, jailed for espionage among other concocted charges). All these conversations (laced with satiric scripted or improved lines) gradually bring on a composite portrait of current Iranian reality.

Full knowledge about Panahi’s previous films and dealt themes may provide a more delightful movie experience. The discussion on capital punishment that commences the narrative refers to “Crimson Gold”; the wailing wife refers to “The Circle”; a ritual involving goldfish (“White balloon”?); the highly opinionated niece talks about the scenario in “Mirror”; and the human rights advocate mentions the case about sports-loving woman, similar to that of “Offside”. These little reference makes us interpret “Taxi” as an exploration into the director’s own-self. It’s as if Panahi’s reflections on distressing political developments & selflessness of Iranian citizens’ intermingled with his own frustrated, cinematic memories. However, director Panahi shows enough showmanship to not turn “Taxi” into a tedious exercise of self-indulgence. The creative beauty with which the director passes through his message is an absolute delight to watch.

Panahi takes satirical jibs at Islamic film-making laws to not show ‘sordid realism’. The absurdities of those rules are elegantly showcased in the conversation between niece and a trash-picking boy. The girl films the boy, taking money off the ground and she calls him to return the money to its owner, so that she can show something ‘broadcastable’ or ‘distributable’ for her class assignment (since the law forbids film-makers to not show an act of stealing). Panahi, once again evokes the ‘sordid realism’ towards the end (in a sadder note) as the lawyer says: “Erase what I said or you’ll be accused of sordid realism”. These wonderfully staged or developed scenes contemplate on cinema’s growing failure to come close to ‘reality’ as well as on the rulers’ desire to transform cinema into something artificial.

“Taxi” isn’t just a one-dimensional, haunting treatise on the Iranian realities. It is also equally mischievous and optimistic. The Nasrin Sotoudeh episode (the woman with roses) and an old neighbors’ story about being mugged portrays how the people have abundance of resilience and compassion to encounter repressions. Panahi’s inability to traverse through the Tehran streets is a sort of playful self-criticism (to insist on his own lack of ability or perception to see all). In few occasion, Mr. Panahi leaves the confines of the taxi, although the camera stays on and records. The switched-on camera could be interpreted as a metaphor for Panahi’s own (mental) confinement that keeps him away from taking on fanciful ventures.

“Taxi” (82 minutes) is a self-referential, satirical and (sordidly!) realistic film, which exhibits a voice that doesn’t want to be silenced. Is it worth watching? For that question, director Panahi himself provides the answer in the film: “All films deserve to be seen. The rest is a matter of taste”.

![Ong-Bak Review [2003]: One of the Finest Martial Arts Actioners](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/ong-bak-screenshot-3-768x416.jpg)