In an otherwise tale of late-life resurgence, “The Blue Trail” (Original title: O Último Azul) flirts with many genres. Like the beautiful curves of the Amazon, it navigates between dystopia, magical realism, and coming-of-age. The use of the 3:4 aspect ratio forces the viewer to get acquainted with its 77-year-old protagonist, Teresa (Denise Weinberg). Mascaro curates an image of Brazil, a not-too-distant image, where anyone over the age of eighty would have to move into retirement colonies where they will be taken care of by the state. Without the burden of caring for their parents, the children would be better equipped to boost the economy.

In this situation, Teresa finds herself caught in the crosshairs of the government. A sudden lowering of the age threshold from eighty to seventy-five makes her an immediate target. When she returns from work, she sees officials putting laurels on her door and presenting her with a medal celebrating how the old should be cherished. Once the ceremonial gestures are over, the government worker tells her that she has worked enough in her life and should now rest and enjoy her remaining days. Her agency as a human being with choices is stripped away.

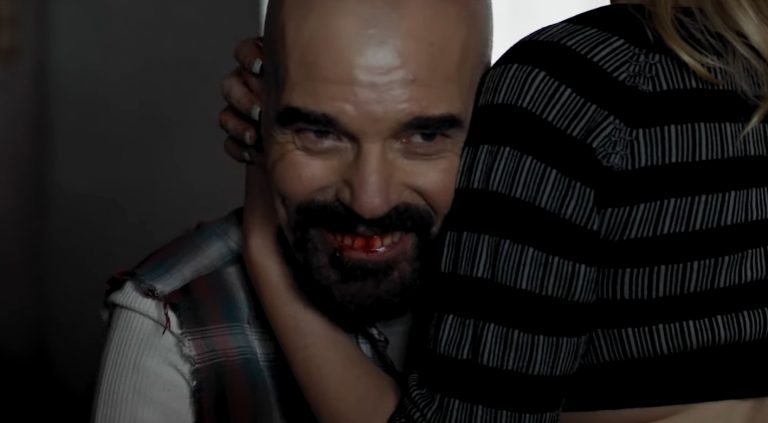

When confronted by her friend, who urges her to go to the colony, she reveals her wish to experience flying at least before she is deported. But when she tries to buy a ticket, she realises that her daughter has legal custody over her and she cannot make card payments without her approval. She then learns of a light aircraft at the Amazonian port of Itacoatiara, where she can pay in cash. She befriends a sketchy boat driver, Cadu (Rodrigo Santoro), who agrees to take her there.

When their boat is delayed, Cadu finds a “blue drool snail” and spins a tale about how its blue dye, when dropped into the eyes, can show the future. With her future already bleak, she somehow tries to fly before she is shipped off. However, unfortunately, it doesn’t transpire, and when she is back home, Teresa is chastised by her daughter as she is shipped to the colony. She somehow manages to escape and later finds a woman, known as The Nun (Miriam Socarras), who sells digital Bibles to the people.

Teresa and the Nun nurture a connection that is warm and pivotal in them realising how they need each other to survive the ordeal. When Teresa finds the same blue drool snail, in a haze, both of them try it, and Teresa goes to a sketchy gambling place called The Golden Fish and wins big before returning to stay with the Nun driving down the picturesque waterways of the Amazon.

The film explores the intersection of ageing, dignity, and erasure. As Teresa’s social and economic capital dwindles, she—like many older people—is quietly pushed to the margins. Stripped of her agency and reduced to a mere number, she is forced into a retirement colony that denies her autonomy. This dehumanisation fuels her longing to break free from the constraints tightening around her. Her recurring desire to fly—never realised—becomes a poignant motif for living on her own terms and a subtle form of resistance against government overreach.

Mascaro also questions the value attached to the life of an older citizen, holding it as a parallel to Brazil’s own history. The answer that he crafts is that of erasure. Authoritarian governments have a tendency to either alter history or erase it completely. By removing the older bodies from the social hierarchy, the film positions itself as a direct critique of how Brazil wants to forget its own history.

The landscape also plays a pivotal role in this narrative, proving to be an active storyteller. The ageing bodies of Teresa and the Nun against the exploited Amazonian backdrop, where the rubber tires are dumped, drive the story forward as to how the relocation colony will be. A dump yard where nobody will ever see what dictatorial euthanasia looks like.

“The Blue Trail” also refuses to shy away from depicting the sexuality of older women. In a tender shower scene between the Nun and Teresa, Teresa’s gaze becomes quietly revelatory; the unbroken shot allows her—and us—to register her own ageing body alongside the Nun’s. A body long assumed to be “past its limit” becomes instead a site of recognition and solidarity.

Later, during a massage, she relishes the masseuse’s touch, reclaiming physical pleasure without apology. The film’s 3:4 aspect ratio further draws the viewer’s attention to their wrinkled, unguarded bodies, especially when they share an intimate embrace while dancing. These moments matter: they insist that older bodies continue to desire, that longing is not the exclusive property of the young, and that ageing does not mark the end of sensual experience.

The film’s core philosophy remains intact. Solidarity will always trump dictatorship. The relationships that Teresa forms briefly and her care for Cadu are something that cannot be understood by bureaucratic norms. Cadu’s emotional outburst and teaching a 77-year-old woman how to drive a boat are also images of perpetual learning and the ability to transform. The magical blue dye is not just a motif to see the future, but it is also an act of defiance where Teresa transgresses the bureaucratic idea of who she should be, and the white fish representing her as she takes on the government and wins.

The Blue Trail’s framing is a timely reminder of how we value history and the people and the nature that represent our historical acts of exploitation and barbarism. We want to erase them quietly, but solidarity and fighting for freedom will always be the final acts of defiance in an otherwise world of constant amnesia.

![Logan [2017]: A Life Lived Well](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Logan-768x432.jpg)