Above everything, Rodrigo Moreno is a filmmaker who does not take kindly to genre conventions. In this new film, you can almost sense him willing to take challenging jabs at the viewer if you attempt to fold the tale he presents, both luxuriously and frustratingly over three hours, into expected twists and turns. The label of the heist film has been carelessly slung over it, which Moreno, who has also written the film The Delinquents (Original name: Los delincuentes), takes simply as a narrative thrust of sorts. The heist, the robbery, acts as the propeller. What unfolds is a leisurely considered plunge into the nature and cost of true freedom.

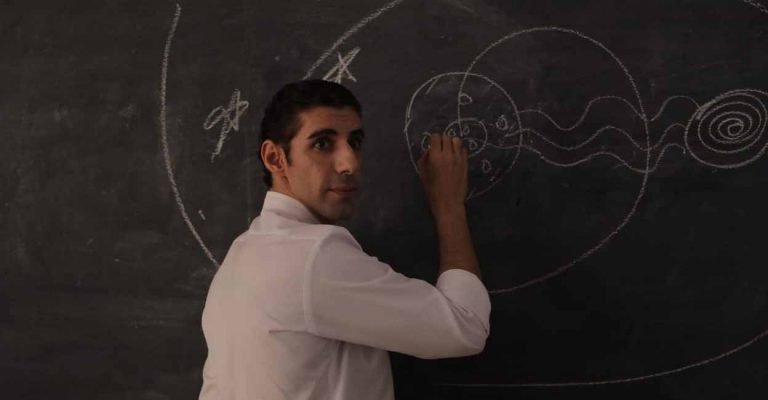

Moran (Daniel Elias) has the job of a treasurer at a bank in Buenos Aires. The long dialogue-free opening sequence makes the viewer follow him around the streets and into the bank. Moran is deeply watchful of everything around him, his eyes fixed on some intention that reveals itself soon enough. These early stretches acquainted us with some of his co-workers and his boss, Del Toro (German de Silva). We realize, however, that Moran isn’t quite friends with anyone despite his having worked presumably quite long at the bank. Moran is distant, and when he does edge close to his colleague, Roman (Esteban Bigliardi), it is strictly to strike a convenient proposition.

Moran has been planning to steal a hefty sum from the bank. With a lot of shrewd savvy and offering a near-no-escape situation for Roman, he manages to rope his colleague into the plan. He lures an initially reluctant Roman to enjoy the spoils of the heist, pontificating to him how it can cut them both from the burden of working another twenty-five years at what both of them see as unrewarding jobs. As per the plan, Moran turns himself to the cops, confident he will be out within three years and can then easily live off the stolen sum, which Roman is entrusted with hiding at his home for the rest of his years.

Of course, things do not pan out as anticipated. Roman may not have been at the bank during the time Moran is seen on CCTV ferreting out the money. This, however, only arms the hawk-eyed investigator called in, Laura (Laura Paredes), to bring him under her scrutiny further. As she goes about drilling all the bank employees, bolstered by Del Toro, who insists the robbery happened because of a collective oversight despite Moran confessing his sole culpability, there are demotions, layoffs, and sharp salary cuts.

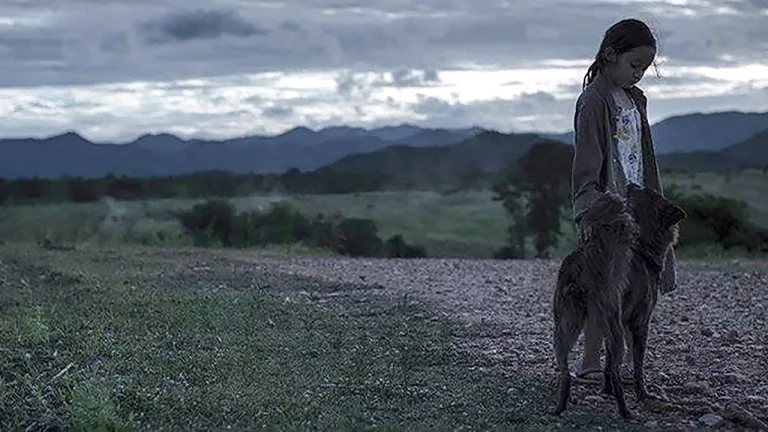

Amidst the severe staff downsizing, Roman can sense himself being acutely watched. The atmosphere at the bank becomes more and more steeped in suspicion. He does not tell his girlfriend either. It gets increasingly anxiety-inducing as he seeks to keep the stash away from anyone’s reach. Moran proposes Roman could trek out to the valleys of Alpa Corral; he knows a hiding spot there among the rocky outcrops. Roman stumbles across a trio in the prairies, little aware their linkages to him run deeper than he could fathom.

It is at this point the film swerves into a strain of storytelling that is beautifully adventurous, loose, untethered, and indulgent at times. This storytelling tendency is very much in the tradition of New Argentine Cinema, populated with the likes of epic, sprawling narratives. The trio Roman Chances includes a filmmaker and two sisters, all of whose ways of leading lives on their land, with no baggage of customary jobs, daily routines that entail picnics, shooting the breeze, and sudden swims, can hold out that quintessential allure for jaded city slickers.

Moreno bungs in a circularity vis a vis these folks and the two principal banking employees, their lives getting more and more entangled, often without the other even noticing. The tale takes several detours and digressions and keeps rolling along with a sort of boundlessness Moran had eyed himself while conceiving his plan.

The director provokes us into grappling with what and how the agency is wielded by the two characters, whose lives have a curious mirroring effect. Both Moran and Roman’s incursions into these desolate, vast prairies unspooling at the outskirts of Cordoba have uncannily similar trajectories. Both men fell for the same woman, Norma (Margarita Molfino).

Moran is deeply inspired by her, passionately telling her he wants to live like her, capable of arranging her day according to her whims, and not obligated to march in with any sort of life-sapping work. The mysterious echoes between the lives of the men are almost cued by an early scene at the bank when there is a bizarre instance of two customers with identical signatures. This inclination of doubling also extends to German de Silva, who also shows up as an elder convict, Garrincha, at the prison, who reveals to Moran the networks of power among the cells.

As Garrincha puts it, the time within the prison yields richer possibilities of looking at freedom and what one can do with oneself than when one is out. This prison space is juxtaposed with the thrilling enormity of the prairie landscapes, whose sequences are shot with bucolic wonder and liveliness by Alejo Maglio. The spark of romance and curiosity that Norma is able to ignite in both the men as they pursue her is exquisitely, joyously evoked. For the men, she unlocks the key to life’s mysteries that have lain long repressed and out of their view.

Rodrigo Moreno’s film is packed yet, at the same time, invites a certain openness that goes beyond languorous storytelling. As much as the men in it trust themselves way too confidently in matters of getting a sustained romantic interest and just generally how the world functions, they also learn and adapt, leading to a finale that is redolent with a charged meeting but withholds us from witnessing it. Its interests are more in how people get shaped and molded with time, while hinting convergences among us may be far more intimately enmeshed than we would like to admit, being all the more fascinating for it.