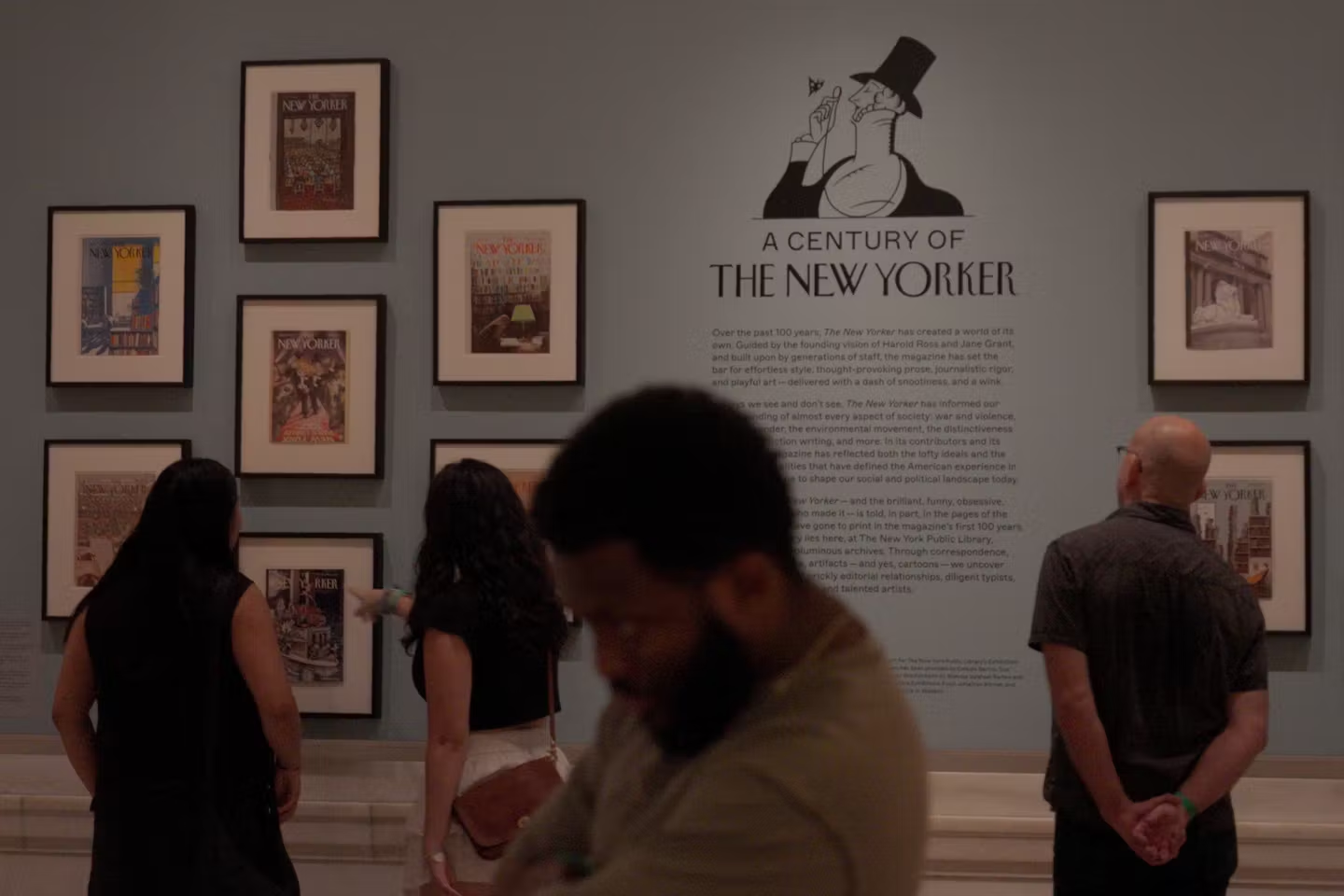

Go to any newspaper or magazine kiosk in a country, which is a staple of its reading community, and one can see the latest edition of The New Yorker sitting quietly at the front. Not boisterous, tantalising images of celebrities or tabloid photographs, but elegantly drawn painted covers adorn the magazine.

The covers showcase the creative freedom, unique style, and mood of a magazine that has been a staple of the culture for a century. From Truman Capote’s true crime-defining work, “In Cold Blood,” to Rachel Carson’s environmental masterpiece “Silent Spring,” which chronicled the destruction wreaked by widely used insecticide DDT, The New Yorker has left an unavoidable mark on politics, art, movies, and above all, fiction itself. So, no surprise, Netflix’s latest take on what makes the magazine giant still resonate with readers worldwide has been drawing so much attention.

Directed by the Oscar nominee Marshall Curry, who is known for stellar work such as “The Neighbor’s Window” and “A Night At The Garden,” the documentary gives viewers an intimate look at The New Yorker’s newsroom as it prepares for its centenary issue. Audiences get a look at pitch meetings where potential stories are discussed, the various processes involving the art style, as well as the somewhat mind-numbing task of selecting cartoons for the pages. The documentary encapsulates it all.

We follow long-time staffers like Nick Paumgarten, Hilton Als, and Richard Brody on assignment as they write about the political divisiveness tearing the United States apart, art created by marginalized communities, and film criticism. The documentary makes you feel as if you are on the streets of New York, talking to people or sitting in a small room, watching the week’s latest flick. The visual piece succeeds in giving the audience a look into what has driven the machine throughout the decades in print and the diverse political and cultural shifts that the literary giant has captured in its writing.

There are many things which set The New Yorker apart, be it its sometimes flamboyant but hard-hitting journalism, its own unique typeface, or its mascot Eustace Tilly, a spectacled, erudite gentleman in a suit which has been on the covers of many prints. The documentary does a great job in capturing and embodying the aesthetics of the magazine it covers. Through well-put animated graphics, viewers understand the origins of its typeface, the editorial legacy behind its mascot, and how the century-defining magazine was founded by Harold Ross and his wife, Jane Grant, in 1925.

The documentary employs a spate of diverse and old newsreels as it discusses the great pieces of journalism pursued by reporters like John Hersey, who, in his piece ‘Hiroshima’, documented the aftermath of the nuclear holocaust on the Japanese people. The visual piece draws on archival material from the period to show how Hersey’s work exposed the brutality inflicted on civilians at a time when American authorities censored images of suffering. Old photographs, newsreels, and excerpts from Hersey’s interviews are woven together through precise contemporary editing.

To showcase the deep impact The New Yorker has left on the culture, the documentary also interviews celebrities like Jon Hamm, Sarah Jessica Parker, and Jesse Eisenberg, to name a few, as it tries to understand the attraction for the magazine.

Julianne Moore lends her voice to the documentary, guiding the viewer from the dingy rooms of Manhattan’s old publishing district, where Harold Ross once pored over story drafts, to the magazine’s present-day corporate offices at One World Trade Center, following its absorption into Condé Nast’s media empire.

Be it the funny, sometimes raunchy cartoons selected from hundreds of submissions or the Pulitzer-winning fiction pieces from writers all over the world, everybody has their story or an opinion about the weekly.

Surprisingly, the documentary also does a good job of taking a critical view of its subject. Before The New Yorker decided to publish a then little-known writer, James Baldwin, the weekly had only published a few pieces by Langston Hughes and one story by Ann Petry. As the poignant voiceover by Moore says, “The New Yorker was publishing a range of voices, but it managed to ignore the lives of over a million New Yorkers.” Representation of people of colour in the weekly was rather limited to servants, porters, and racist caricatures. The young writer’s piece would have a profound impact on the literary landscape.

Baldwin’s “Letter from a Region in My Mind” would expound on his experiences of growing up black in a racist country, his years as a preacher, and subsequent disillusionment with faith and the rise of the Nation of Islam. The essay became a philosophical pillar of the then-nascent civil rights movement in America and also drew attention to the lack of intellectual space provided to minority communities.

With the use of archival footage and modern graphics, audiences are transported to an era of racial divisions. However, for all the promises of such an essay, the New Yorker ran the brilliant piece along with an advertisement depicting a black servant. The documentary rather candidly touches on such sensitive topics, thus giving it credibility as it smoothly avoids the pitfalls of revisionism.

In a heartfelt moment, Remnick reminisces about his parents, who were both disabled at a young age, as he looks intently at an old family photograph and discusses his own experience of raising an autistic daughter. The camera lingers on Holding the Note, his collection of profile essays on musicians and performers of our time, as he reflects on how professional fortune coexisted with personal struggles that ultimately shaped who he became.

As the legendary journalist summarizes, “I have had incredible strokes of good luck, and I have had incredible strokes of bad luck.” It is in moments like these that “The New Yorker at 100” truly shines, showing the stories of staffers and editorial leaders who bring the magazine to the table. It also tactfully and with humour confronts the fact that the magazine has a reputation for being snobbish, with its knack of old school typography to overzealous use of commas to usage of words sometimes more fit for a museum.

Editing can really make or break a visual project. In its aesthetic and graphic design, the docu-feature imbues the feel of a magazine with animated texts, typefaces, overlays, and texture. Like turning over the pages of The New Yorker, the documentary often uses the effect to transition between frames and discuss time periods, as paper animations are used to bring life to images of writers from another era. We, as the audience, also traverse The New Yorker under the guidance of its past editors, as William Shawn took the mantle after Ross’s death.

We follow present editor David Remnick, the fifth editor of the weekly since its inception, as he follows his daily routine. Be it discussions with his staff on potential developments and story leads or making editorial choices regarding the magazine cover, Remnick has been at the job since 1998.

The film also traces shifts in the media landscape through the magazine’s leadership changes, beginning with the departure of long-serving editor William Shawn, followed by the swift succession of Robert Gottlieb and Tina Brown. Brown’s endeavour to modernise the magazine saw her focus more on topical coverage with flashy interviews of celebrities, and ultimately, her untimely exit is also well covered by the documentary.

This raises a simple question: why does such a deeply human story behind one of the world’s most famous magazines fail to reward a second viewing? Despite all the elements of what could have been a timeless piece of documentary behind a coveted and famous newsroom, the narrative thread is rather conventional, predictable, and sometimes tedious.

The documentary also, at times, comes across as a marketing tool for The New Yorker. The newsroom is often portrayed as a place of bonhomie between writers and bosses, while journalistic spaces are often further from that. It is this polished, corporate sameness—often bordering on the formulaic—that weighs down many Netflix documentaries, and it does the same here. The film shows little interest in taking formal or editorial risks.

In an age of ever-diminishing space for independent media and increasing political interference, how will The New Yorker wade through the sea of misinformation and continue to produce strong reportage? In an era of anti-intellectualism, will the magazine be able to shed its snobbish reputation and become relatable to the common folk out there? All these potential story beads remain unexplored.

What “The New Yorker at 100” ultimately delivers, despite its access to one of the country’s most influential newsrooms, is a largely vanilla portrait. It makes for a perfectly serviceable one-time watch, particularly for readers and journalism enthusiasts, but it neither invites nor rewards repeat viewing.