With over 38 films (33 Japanese films produced by Toho and five American films), television series, comic books, and video games, the fictional Kaiju Godzilla has become an international pop icon. Some might argue that he had been the first kaiju that had broken through the mainstream, and that won’t be a bad argument. Since 1954, when the first Godzilla film was released, Godzilla has undergone many iterations. Created by director Ishiro Honda as a metaphor for nuclear testing and the consequent horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Godzilla slowly evolved from antihero to outright heroic to a kids’ icon. Threats and the tonality of the movies also took a campier route until a reboot would ostensibly bring him back to his horror roots.

True to the structure of a Godzilla film, the best or most effective ones would comment on a specific segment of Japanese society, be it the environmental degradation of the late 1960s, the unchecked horrors of crony capitalism, the apathy of Japanese society, or its propensity to not learn from the mistakes of its past. In some cases, the Godzilla films would also become Japan’s calling card to the rest of the world by showing its progress through technology or even storytelling skills. Thematically, almost all of these Godzilla movies are always about humanity’s hubris and how the aftermath of the destruction convinces humanity to do better (whether that referendum sticks in the next film is a different matter).

Eras

Any long-running franchise at some point or another would have to undergo a creative reset—a reboot that could be classified as either hard or soft, whether it is setting the films in a completely new continuity or shifting the tonalities depending on the market when the movies are being released. Godzilla films are widely divided into four separate eras:

- Showa Era (1954 – 1975)—The story begins with the original “Gojira” (1954) and concludes with the “Terror of Mechagodzilla” (1975). It is characterized by somewhat loose continuity in the beginning, slowly tightening by the end of the 1960s. The evolution of Godzilla from a destructive force of nature to a campy heroic figure that is almost anthropomorphized occurs here, along with the introduction of Godzilla’s core rogues gallery that persists to this day.

- Heisei Era (1984 – 1995) -A reboot of the series would occur ten years later with “The Return of Godzilla” (1984), which acts as a direct sequel to the original and removes all the continuity of the Showa films. The Heisei era spans a series of seven films set in a single timeline with somewhat tighter continuity. It also focused more on Godzilla’s science and biological nature, with most of its villains formed as a direct result of Godzilla’s presence and his actions leading to tinkering via human hands.

- Millennium Era (1999 – 2004) – The third reboot after the end of the Heisei era occurred as a response to the American travesty that had been the 1998 Godzilla film directed by Roland Emmerich. Each of the films during this era had staggered continuity; thus, the overall era is treated as an anthology. Almost all these movies had continuity, with only the original film being the closest reference. The movies “Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla” (2002) and “Godzilla: Tokyo SOS” (2003) are the only ones sharing direct continuity, as well as with the original Godzilla film and the 1961 Mothra film.

- Reiwa Era (2016 – Present) – Similar to the Millennium era, Toho would again reboot with 2016’s “Shin Godzilla.” The anime trilogy of “Godzilla: The Planet Eater” doesn’t share continuity with “Shin Godzilla” or “Godzilla Minus One” (2023). The reboot occurred after Legendary Pictures’ American Reboot and the creation of a unified Monsterverse, whereby Toho decided to expand both the Godzilla franchises (Japanese and American) simultaneously. The Reiwa era showed a sense of creative highs as well as the lowest of lulls, and it’s still ongoing.

Caveats –

- Only the movies featuring Godzilla are taken into account here. Thus, the solo kaiju films of the Showa Era (“Mothra,” “Rodan”) or the entries in the Monsterverse not featuring Godzilla (“Kong – Skull Island”) but would be included in the timeline aren’t considered.

- Only the officially released feature films are being considered. That removes all the short films Toho released and the fan films on YouTube.

- No television series featuring Godzilla are being considered – animated or live-action

- As always, this is a subjective list, considering both the amount of fun one can have in a Godzilla feature and its overall quality as a film.

Without further ado, let’s dive into the top 10 Godzilla movies being made so far –

10. Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla (2002) | Millenium Era

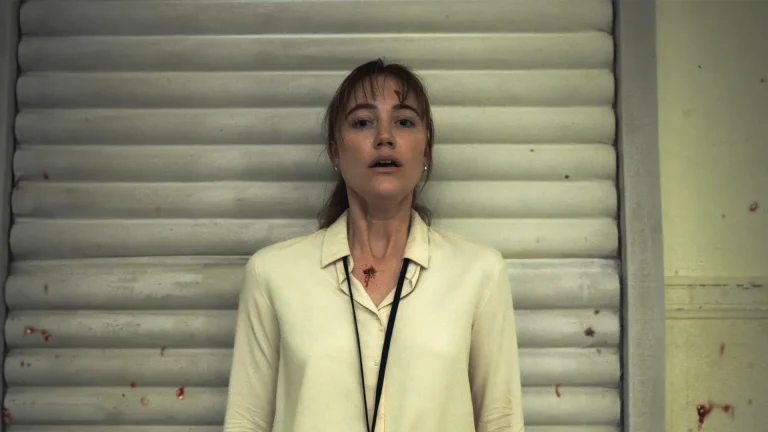

Forty-five years after the original film’s events, the appearance of a new Godzilla prompts a fateful encounter between the beast and the forces of the JSDF (Japan Self-Defense Forces). A tragedy befalls Maser cannon technician Lieutenant Akane Yashino, for which she blames herself. To ensure a countermeasure, scientists are instructed to build a new mecha over the skeletal remains of the original Godzilla. As the cyborg is sent into battle against Godzilla, it is revealed to harbor the restless soul of the original monster, which complements the restlessness of Akane’s soul as she is forced to pilot the mecha.

This is easily the best of the four films featuring MechaGodzilla in this franchise. One of the reasons why the first half of this Kiryu saga lands is because, taking into account the weird premise of creating Mechagodzilla over the bones of the original Godzilla from 1954, it expands on that premise to explore the sentience of the mecha. Also, unlike many Kaiju movies, the human characters, especially the protagonist in this one, are incredibly compelling.

While a badass fighter in her own right, the character of Akane is imbued with a sense of quiet compassion, underscoring her determination, making her a fascinating character to follow, especially in the film’s final act. The overuse of digital effects in the Millennium era helps in the design of the action set pieces featuring MechaGodzilla, showing a much scrappier iteration eager to fight Godzilla from up close rather than utilizing beams and long-range weapons in its arsenal. This gives the fights an added dose of excitement.

9. Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964) | Showa Era

Two journalists discover a strange blue-grey object (revealed to be an egg) near a typhoon wreckage. The egg is reclaimed by greedy entrepreneurs who plan to build a hotel around the egg. The Shoubijins of Infant Island, foot-long fairies, and priestesses worshipping Mothra plead for the return of the egg, which is revealed to be a new Mothra’s egg and are aided by the journalists. Amidst all this hullabaloo, Godzilla arises near Nagoya. Now, the priestesses of Infant Island must decide whether to enlist Mothra to aid the people of Japan against Godzilla.

To capitalize on the popularity of the Mothra film from 1961, Toho decides to face Mothra against Godzilla in this 1964 iteration. Thus, elements of Mothra’s mythology (the Shoubijin, Infant Island, the catchy song, and dance sequences) are all repeated here. The fantasy elements become a staple of Godzilla, especially Mothra mythos, while Mothra’s design becomes iconic, as is her presence in the canon of Godzilla. The fact that this film comes out ten years after the original “Gojira” (1954) makes sense once you visualize the Godzilla segments in a vacuum and how much the destruction and a couple of shot selections mirror the original.

In this, Godzilla is much more effective as a destructive force than in his earlier appearance, so having Mothra as a foil works. The bout between Mothra and Godzilla, too, is quite watchable, with some sequences being especially cool: Mothra pulling Godzilla by its tail and dragging it, or her wingspan producing winds of such ferocious knots that they stop Godzilla right in its tracks.

8. Godzilla (2014) | Monsterverse

Ford Brody’s (Aaron Taylor Johnson) return home from the Navy, and his reunion with his family is interrupted when he is forced to go to Japan to help with his estranged father, Joe (Bryan Cranston). They are both swept up in the middle of an ancient battle between Godzilla and the MUTOs (Massive Unidentified Terrestrial Organisms). The creatures leave destruction in their wake as they make their way toward San Francisco, the final battleground.

To completely construct a Kaiju movie as a disaster film hearkens back to a similar premise to the original Godzilla. While the divisiveness of this iteration is understandable, being shrouded in darkness and Edwards’ stubbornness not to provide catharsis via the money shot, it all feels strangely like a boots-on-the-ground story. Like most Godzilla interpretations, the movie tries to show an individualist perspective to an extent via Aaron Taylor Johnson’s character. Still, it works better as an overview of a disaster zone left behind by the Kaiju’s fighting, uncaring about the carnage being wrought.

Through that lens, “Godzilla” (2014) comes the closest an American interpretation manages to show the big guy as a force of nature rather than the superhero he is shown to be in the later incarnations of the Monsterverse. Few Monsterverse, or for that matter, few Godzilla films, look as gorgeous in blood-red hues as this one does.

7. Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack (2001) | Millennium Era

The events of the 1954 film have become a distant memory for the people of Japan, when the destruction of a US submarine off the coast of Guam raised alarm bells, especially after footage showed the presence of a giant creature’s fins. Meanwhile, an intrepid reporter who works as part of a film crew creating low-rent horror docudramas is caught in the middle of a mysterious earthquake. She later learns of a monster being sighted as the cause of the earthquake before discovering the myth of mysterious guardian monsters responsible for protecting the planet. She soon finds herself caught in the crossfire of all these guardian monsters battling against a Godzilla possessed by the souls of those killed in the Pacific War.

Director Shuske Kaneko attempts to make this film a jumping-on point by imbibing all these monsters with a supernatural bent. At the same time, the world around the main event resembles the reality of the current era. Making Godzilla a monster possessed by the souls of the soldiers killed in the Pacific War gives him a ferocity akin to a demonic possession. Rarely has Godzilla felt so mean-spirited. In contrast, the idea to integrate Mothra, Baragon, and, surprisingly, King Ghidorah as supernatural entities akin to guardian monsters is a subtle way of commenting on how the entire franchise of Godzilla has integrated itself within the lexicon of Japanese culture. It also allows the franchise to dabble into the horror roots as well.

While the human story starts quite slowly, as the battles escalate, the reactions of the humans become conjoined with the director’s deliberate focus on the carnage and violence. Its reaction against the forces of the unknown makes the human story more relatable from a macro perspective. The special effects, the visuals, and the overall fight choreography of the monsters truly make this film feel epic in scope. With Godzilla almost feeling unbeatable, it is a different feeling for anyone who has followed the franchise to see the big guy as a true-blue antagonist, but here it works.

6. Shin Godzilla (2016) | Reiwa Era

The reboot and the first installment of the Godzilla franchise in the Reiwa era, under the umbrella of Hideaki Anno and Shinji Higuchi, follow the Japanese administration suddenly falling over themselves and into the bureaucratic red tape as they scramble to deal with the presence of a strange gilled monster (Godzilla) who evolves itself as soon as it is attacked. Meanwhile, a ragtag group of researchers and scientists act against the web of bureaucracy to search for a solution to the Godzilla problem before time runs out.

It’s fascinating how this reboot mirrors the original as a political allegory, at least in terms of its premise. The way Anno captures one’s disdain for the government, the bureaucracy, the inherent stasis, and the viciously circular nature of decision-making make it a strange but necessary complement to a “kaiju” film. This is why it is surprising how optimistic the government’s ethos in the movie is.

It becomes a stimulating exercise to see a movie balance both the kaiju destruction, showcase the awesome power and potential, and show the strength of a government body and group firing at all cylinders and working together without getting bogged down in the muddy, turgid nature of bureaucracy symptomatic of democracy. The design of Godzilla, from its gilled form to its bipedal evolution, reminds me of Anno’s quirky lens, evoking Hedorah’s design sensibility from “Godzilla vs. Hedorah” in its abstraction and ever-changing nature.

5. Godzilla vs. Destoroyah (1995) | Heisei Era

The final installment in the Heisei era of Godzilla follows Godzilla, whose heart is similar to a nuclear reactor uncontrollably undergoing fission, as it emerges to lay siege to Hong Kong. At the same time, horrible new crustacean-like creatures, which had been hidden beneath the Earth’s core for millennia, emerged during the construction of the Tokyo Bay Aqua Line. Mutated as a result of the oxygen destroyer, the same weapon designed by Dr. Serizawa that had resulted in the death of Godzilla in the original film, the Precambrian-era creatures soon combine into several human-sized crab-like creatures and begin terrorizing Japan.

The Heisei era had promised to forego the camp nature of the earlier era, bringing in a focus on the science element of the proceedings, though not necessarily grounded. And while the Heisei era is guilty of being inconsistent, this final installment brings the serious tonality back around. With the director of “Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II” and the screenwriter of “Godzilla vs. Biollante,” the final film serves not just as a closure for that era but also as a true homage to the franchise as a whole. The 40th-anniversary era of the franchise ensures a look back, and “Godzilla vs. Destoroyah” does that by directly connecting the kaiju of this film to the final weapon utilized to defeat Godzilla in the original.

In a way, it is Godzilla fighting against what had been responsible for incapacitating him 40 years ago, but Godzilla also has to retroactively deal with all the events in the last seven films, which has turned him into a ticking time bomb. The design of the monsters, as well as Godzilla on the verge of meltdown, is extraordinary, but what truly struck me is how the movie can mine emotions from Godzilla’s plight. The final 20 minutes are truly something very different from the traditional installment of this franchise, dependent on final fights with the humans in the background commenting.

While the humans are actively contributing to the fight, the movie doesn’t forget to comment on Japan’s overuse of nuclear power and how Godzilla’s situation is a form of atonement for their misdeeds. “Godzilla vs. Destoroyah” wraps up all loose plot threads of the Heisei era, utilizes the baby Godzilla trope impressively well in commenting upon the legacy, and, like all best pulp films, ends with a tease of continuation even as this era ends.

4. Godzilla vs. Biollante (1989) | Heisei Era

After the events of “The Return of Godzilla” (1984), an arms race began to form between corporations over the ownership of Godzilla’s cells. Concerned over Godzilla’s return, the government uses these cells to create a new bioweapon, the Anti-Nuclear Energy Bacteria (ANEB). To ensure the creation of the weapon, they seek the help of a geneticist, whose experiments result in the formation of a kaiju that is made with the cells of Godzilla and a plant, as well as the blood cells of his deceased daughter.

“Godzilla vs. Biollante” feels the closest to a Michael Crichton thriller dealing with humanity’s proclivity to push science towards boundaries that shouldn’t have been pushed in the first place. It is also one of the few Godzilla movies where the human element is as strong, if not more robust than the monster battles. There are genuine emotional stakes about a scientist dealing with the loss of his daughter that would lead him to indulge in experimentation. What truly sets this film apart is the design of Biollante and its inception. Gorgeous aesthetics and amazing puppetry akin to “Little Shop of Horrors” make Biollante one of the best new monsters in Godzilla’s lore. The cinematography, too, is exquisite—one of the best the Heisei era would offer.

3. Godzilla vs. Hedorah (1971) | Showa Era

Godzilla might be facing his greatest nemesis yet: Hedorah, an amorphous alien species of the Horsehead Nebula who is transported to Earth by a comet and feeds on pollution enveloping the Earth, evolving into a poisonous acid-secreting sea monster. Its ability to spew toxic sludge and mists of sulphuric acid makes this a terrifying menace that neither the populace of Earth nor Godzilla would be able to solve.

Even amidst the Showa-era Godzilla films, Yoshimitsu Banno’s lone kaiju offering is the weird stepchild. It is not only trying to respect the sensibilities of the previous decade of Godzilla films, but in ushering in a new decade, it is becoming a reflective mirror of the original Gojira film. If the original Gojira was the response to an atomic blast and the nuclear arms race, “Godzilla vs. Hedorah” is the response to pollution.

A clear response to the unnatural deaths from 1912 to 1961 as a result of unregulated pollution, “Godzilla vs. Hedorah” is striking and punk-rock. Banno creates a visual palette far different from that of the usual Godzilla films. It comes off as part PSA via the kid and his scientist father explaining the process of Hedorah’s growth, intercut with animation resembling a child’s drawings showing Hedorah swallowing everything in its path. The opening credits recall that of James Bond, with a jazz number sung by a ballroom singer, but the lyrics admonish and point out heavy metal pollution in the seas, urging humans to give it back. The set pieces, too, are vastly different.

The effects of Hedorah’s abstract form and power, as well as Godzilla’s attacks, are shown in gruesome fashion, with civilians drowning in sludge, flowers wilting away, or patrons of a nightclub barely escaping being drowned by Hedorah’s sludge. As a result, even Godzilla’s confrontation with Hedorah has stakes. Banno keeps away the goofy antics usually associated with the Showa era until the very end, choosing to instead go forth with dark, eerie master shots of Godzilla facing off against Hedorah like a boxer challenging an opponent.

2. Godzilla Minus One (2023) | Reiwa Era

In a true blue reboot similar to “Shin Godzilla” (2016) but set post-World War II, Takashi Yamazaki posits a simple question through the perspective of a former kamikaze pilot suffering from PTSD and being a personification of the country barely surviving after the war: what happens when a giant monster termed Gojira attacks an already devastated and wounded country? How will they fight back, or will they be able to fight back?

When Godzilla debuted back in 1954, it had been an allegory of the end of World War II, the futility and destruction of nuclear annihilation, and yet the resilience of a country to rebuild itself was still smarting from the destruction. Takashi Yamazaki chooses this setup but goes a step further. He takes the sentiments of war and hones them sharply towards the soldiers, towards imposter syndrome from a survivor’s perspective, wracked by PTSD and guilt over being unable to save his comrades, and thus, at length, chooses to focus on the soldier realizing and finding a new life to build, like his country, slowly regaining its status back. The presence of Godzilla becomes intricately tied to the harrowing ordeal of Japan and its citizens.

Its presence, stripped of all personalities beyond a hulking, terrifying rage monster, a sheer force of nature, and treated with the same veneration-heavy dread that the shark from “Jaws” receives, becomes tantamount to the movie’s narrative. When these themes weave in so intricately with the sheer breathtaking nature of the visuals of Godzilla’s destruction and awesome power, you are left with the push and pull of excitement and dread—enjoyment of the visual splendor and yet investment in the characters. This is a director who knows the allegorical power of Godzilla, the symbolism of the kaiju, and the weight it carries, and executes it to near perfection.

1. Godzilla (1954) | Showa Era

After ships are sunk, they explode and sink near the coast of Odo Island. A world-renowned paleontologist leads an expedition. The expedition discovers the presence of the 50-foot-tall kaiju Godzilla, who soon begins a rampage through Japan, leaving destruction in his wake. The grand-daddy of all Kaiju movies, a humanist commentary about the nuclear holocaust from the perspective of the victims, “Godzilla” (1954) gains even more impact during that era due to directly commenting on the Bikini Atoll incident that had resulted in nuclear fallout being showered upon a Japanese fishing vessel a few months before the movie would be released. From the cultural and political overtones of World War II, the Japanese public connects with Godzilla as they view him as akin to the personification of the trials and tribulations faced by the Japanese.

Calling the images allegorical would be taking away their power—of burning buildings, overflowing hospitals, and children affected by nuclear fallout—and somehow gains even more precedence if one considers that the American version of the movie would be faced with extensive recuts, with a voiceover of an American reporter somberly recounting the events. Somehow, the denigration of the recut only increased the thematic depth of the original.

However, Honda’s strength also lies in its characters. In showcasing them as humans reacting to an incident so harrowing, the melodrama itself isn’t entirely enough, almost coming off as subtle in response to the horror. Humanity trying to shelter themselves through love or human connection could be the only possible solution; empathy affords a B-movie genre A-lister status. Major franchises have been active as long as, if not longer than, this one, but there are very few franchises whose progenitor grows in stature the more you explore the contours of the franchise.