Seven decades after the film industry’s brightest and best began to stroll down the French Riviera, the Cannes Film Festival remains the highlight of a cinephile’s year – two weeks of glitz and glamour and ceremonious premieres to elevate the status of some of the world’s greatest films and filmmakers. It has been a hotbed of creativity and innovation through the years, helping gain wider audiences for exciting film movements across Europe and greater recognition for the film cultures of East Asia and North Africa, particularly.

Almost as rich a tradition has emerged in some quarters of critiquing Cannes and what it stands for. Does its status as the doyen of arthouse film render it an elitist institution? Has it ever really given female or Black directors fair representation? Such worthwhile discussion can only exist due to the festival’s ubiquity and the invaluable platform it can provide to further the lifetime and relevance of this medium we love so much.

Disclaimer

The following 30 films have been ranked by the writer’s personal opinion, not strictly trying to gather consensus. The list may be updated in the future for additional Palme d’Or winners.

30. Anatomy of a Fall (2023, Justine Triet)

The most recent Palme d’Or winner is a stern procedural underpinned with a touching family dynamic. Sandra Huller stars as an author who stands accused of murdering her husband, with their partially sighted child placed at the forefront of a criminal trial and media circus. Much of the film is as icy as its foreboding Alpine backdrop, but shines most in its moments of levity: the heartfelt connections felt by Sandra towards her son and her lawyer shared in quiet physical intimacy. Between this and her previous effort Sibyl, Justine Triet is proving her credentials as one of Europe’s most accomplished upcoming directors, one capable of generating intrigue and empathy in equal measure, and a particularly strong helping hand to incredibly talented performers such as Huller. Next year’s Palme winner has some work to do if it wants to rival Anatomy of a Fall’s assertive power.

- Jury president: Ruben Östlund

- Also in competition: The Zone of Interest

29. Miss Julie (1951, Alf Sjöberg)

Both director Alf Sjöberg and playwright August Strindberg are legends of the Swedish stage, but in 1951 the former was able to bring the Palme back to Stockholm for his second victory with this riveting adaptation of Miss Julie, powered by fine performances from Anita Björk and Ulf Palme. For the uninitiated, Miss Julie is a dramatic work from 1888 dealing with the complex intersection of class, sex and gender in aristocratic society, a plot transferred to scenic real life locations and shot with gusto in this screen translation. Although Sjöberg works here without frequent collaborator Ingmar Bergman, he is nevertheless pens an exciting script which takes refreshing liberties to the source material. These changes are necessary to render an old text new again, reminding audiences that the divisions between classes remain sadly irreconcilable to some. Sjöberg would be the last Swedish director to win the award until Reuben Östlund would win for The Square and Triangle of Sadness, two satires exploring similar themes over 60 years later.

- Jury president: André Maurois

- Also in competition: All About Eve

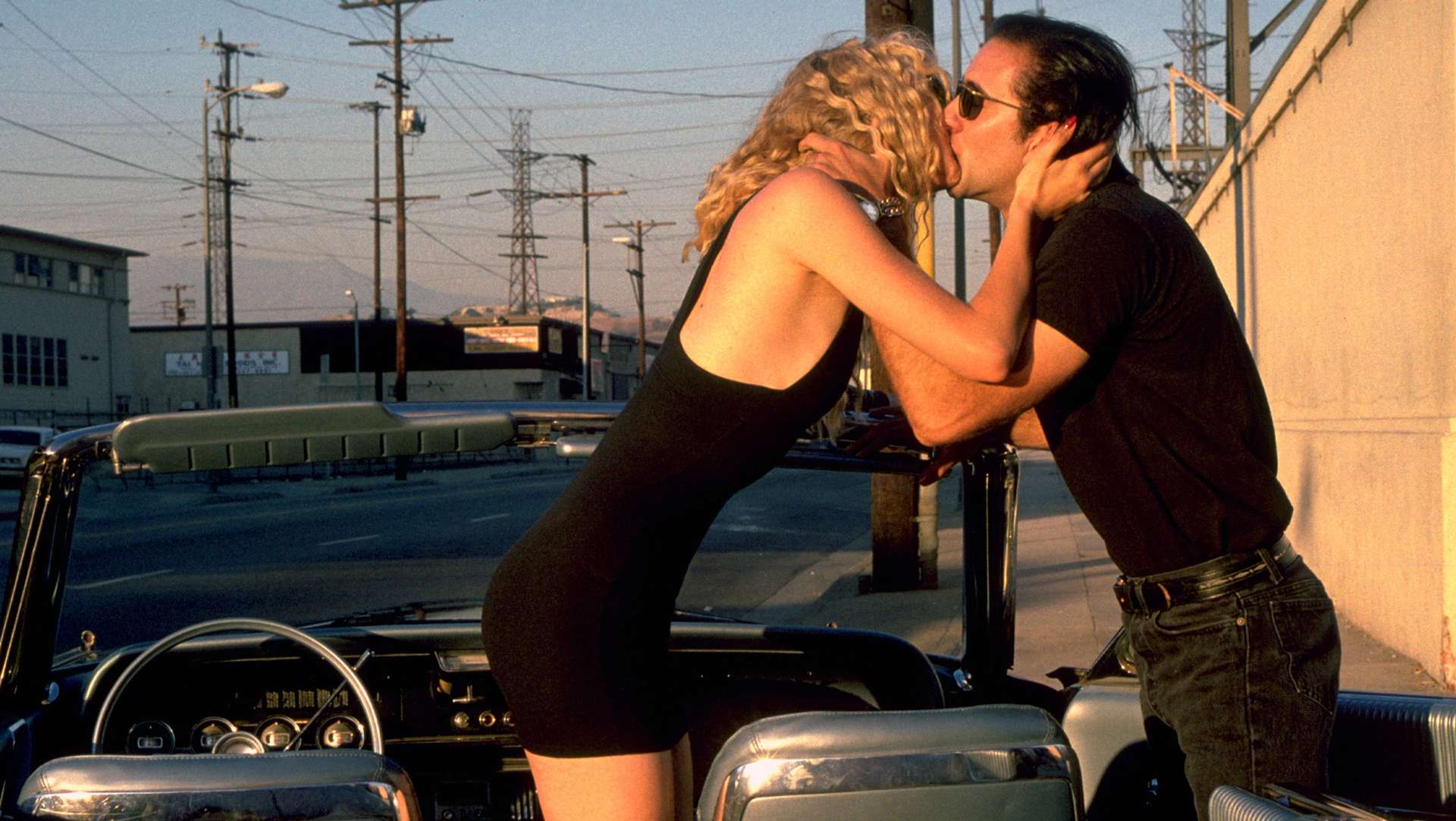

28. Wild at Heart (1990, David Lynch)

It may surprise you to hear that Lynch’s only Palme d’Or came for this wild card, rather than the more cerebral Mulholland Drive or conventional The Elephant Man. Instead the jury was most charmed with this enthralling of a life on the run that demonstrates the great surrealist director at his most energetic and unhinged. Much of the manic tone is down to Nicolas Cage’s lead performance, among his very finest, supplemented by real-life mother-daughter pairing Laura Dern and Diane Ladd who are commendably unafraid to go wherever this screenplay takes them. Electric editing and cinematography propel the narrative and reflect the compulsive nature of two leads setting their lives ablaze in gorgeous hues. Such a brave and audacious film doubtless deserved the plaudits, and it’s a crying shame that this fever dream goes overlooked nowadays in Lynch’s oeuvre.

- Jury president: Bernardo Bertolucci

- Also in competition: Cyrano de Bergerac

27. The Working Class Goes to Heaven (1971, Elio Petri)

An example of Cannes using its platform to showcase progressive and socially conscious cinema, The Working Class Goes to Heaven is a rare beast of a black comedy that manages to embrace the solidarity of working class labourers and find comedy where others would place trite idealism. Director Elio Petri cut his teeth with ‘Eurocrime’ thrillers in the 1960s and brings a similarly charged, propulsive energy to his work here. In the film, worker Lulu, played with remarkable volatility by Gian Maria Volonté, loses a finger in an industrial accident and struggles to meld his fundamental egoism (and sex drive) with the altruistic aims of the revolutionary groups he joins. In this incisive and entertaining examination of the class divide Petri distinguishes himself as one of Italy’s premier auteurs, and a worthy winner of the top prize.

- Jury president: Joseph Losey

- Also in competition: Solaris

26. The Lost Weekend (1945, Billy Wilder)

Wilder’s The Lost Weekend is one of few movies to have won both the Palme d’Or and Best Picture (most recently Parasite repeated the trick), indicative that its undeniable quality and sobering impact of this tale of alcoholism. The drama is truly anchored by Ray Milland’s performance as a writer addled by the allure of the drink, and Jane Wyman’s equally impactful turn as his long-suffering love. The complex web of emotions that exist between the two is compellingly written and performed, and successfully untangled by Wilder’s shrewd direction. Hot on the heels of the previous year’s Double Indemnity, Wilder here dips his toes into austere drama, showcasing the versatility, range and depth of feeling in his filmography that would make him one of the defining Hollywood directors of the era. Under his watchful eye, the tragic evil of addiction is shown in especially stark light.

- Jury president: Georges Huisman

- Also in competition: Wilder shared the award with several films: Brief Encounter, Torment, The Last Chance, María Candelaria, Men Without Wings, Neecha Nagar, Red Meadows, Rome Open City, Pastoral Symphony, and The Turning Point

25. Taxi Driver (1976, Martin Scorsese)

Once considered the masterpiece of Martin Scorsese’s storied career, Taxi Driver has begun to take a backseat (pun intended) to his more mature, often mafia-focused, dramas in recent critical evaluations. After all, his 1976 award-winner plot has been so often imitated that the ‘angry white man driven crazy by society’ arc seems hackneyed through modern eyes. But what Todd Philips’ Joker and its ilk fail to understand about the original is the depth and rich characterizations of Paul Schrader’s screenplay and, of course, the technical mastery of both Robert De Niro’s performance in front of the camera and the legendary work of Bernard Herrmann off it.

- Jury president: Tennessee Williams

- Also in competition: Cría cuervos

Also Read: 10 Best Films of Martin Scorsese

24. Sex, Lies and Videotape (1989, Steven Soderbergh)

Among the myriad accomplishments of Steven Soderbergh’s unique career in film, the fact that he became the youngest ever Palme d’Or winner in 1989 for Sex, Lies, and Videotape – the film that fully pronounced a new age of American independent cinema – seems to get overlooked. Set in the baking heat of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, the film’s overriding message isn’t groundbreaking; instead, it is the machinations of its plot and the way it unfurls that makes Sex, Lies and Videotape such a subversive and compelling watch. There was nothing quite like it in 1989, and its legions of imitators only cemented further the prodigious clarity of Soderbergh’s vision.

- Jury president: Wim Wenders

- Also in competition: Do the Right Thing

The 15 Best Steven Soderbergh Movies, Ranked

23. Gate of Hell (1954, Teinosuke Kinugasa)

To talk about Gate of Hell, the viewer must first remove their jaw from the ground, where it has no doubt spent the last hour-and-a-half gazing at the inimitable pallet and meticulous compositions of Kinugasa’s first color feature. That a director renowned for his silent horror masterpiece A Page of Madness (1926) proved such a dab hand at a classic ‘jidaigeki’, years before Kurosawa reinvented the wheel is a testament to his versatility and visual storytelling. The plot is more than happy to play second fiddle here, as a tale as old as time is elevated by the craftsmanship of the highest order from Kinugasa and DP Kōhei Sugiyama, who capture an ancient setting as if it were a fairytale.

- Jury president: Jean Cocteau

- Also in competition: From Here to Eternity

22. The Leopard (1963, Luchino Visconti)

A stone-cold classic of ‘world cinema’, The Leopard debuted in America to lukewarm reviews for an edited, dubbed version, whilst the original won countless plaudits and the big prize at Cannes. This is to say that to appreciate and understand Visconti’s most famous film, you must view the full breadth and scope of his vision in all of its 3-hour glory. Like the characters it portrays, The Leopard is preoccupied with ornate tradition: a sweeping epic about historical sea change starring beautiful movie stars, shot in marvelous technicolor. Yet this grand scope does not equate to distance from the text, as Visconti relates his personal stakes in Italian unification as the son of a former Duke.

- Jury president: Armand Salacrou

- Also in competition: Harakiri

21. The Piano (1993, Jane Campion)

Jane Campion became the first female winner of the Palme d’Or for The Piano, a searing drama that highlights her keen ability to outwardly explore feminist ideas by examining the damaged inner workings of masculinity. This is balanced with Campion’s clear preoccupation with formalist filmmaking as each shot and each movement of the camera is crafted to make the viewing experience as luxurious as possible for the viewer, a director truly at one with her control of the craft. In this context, actors can become set dressing, but not when Holly Hunter, Sam Neill, and Harvey Keitel are around delivering career-best work, arguably all to be shown up by the power of an adolescent Anna Paquin.

- Jury president: Louis Malle

- Also in competition: Naked

Also Read: All Jane Campion Movies Ranked

20. The Wages of Fear (1953, Henri-Georges Clouzot)

Genre cinema remains sadly underrepresented among Cannes alumni, but though it is often not mentioned in this bracket, Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Wages of Fear is about as straightforward a thriller as one can get. The stakes are set high, and the eccentric natures and differing goals of the characters are established early, ensuring that the thrilling set pieces of the next two hours are scenes of such hair-raising tension that they can be hard to look at. The film is bound for comparison with its American remake, Sorcerer, but there’s something about the classic age sheen of The Wages of Fear, contrasted with the gritty reality of its storyline, that gives it the edge.

- Jury president: Jean Cocteau

- Also in competition: Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday

19. Pulp Fiction (1994, Quentin Tarantino)

If a young Steven Soderbergh’s triumph for Sex, Lies, and Videotape in 1989 marked the breakthrough of American dining cinema, then Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction winning five years later marked the movement’s epoch. This postmodern genre hybrid remains, to a whole generation (or two), the cinematic embodiment of cool. Countless scenes, needle drops, quotations, and characters have seeped into the pop culture lexicon through its enduring acclaim and popularity. Watched today, Pulp Fiction remains an engaging, but most of all hilarious, watch, propped up by a raft of career-best performances from its cast and, of course, some of the sharpest dialogue of its day.

- Jury president: Clint Eastwood

- Also in competition: Three Colours: Red

Also Read: All Quentin Tarantino Movies Ranked

18. The Tree of Life (2011, Terrence Malick)

The Tree of Life is the most recent American film to win the Palme d’Or (11 years ago, an unusual drought for the prize’s most successful nation), but in truth, the work of Malick transcends boundaries of language and nationality. Soaring above the boundaries of narrative, this tone poem instead looks to the heavens and the annals of time to explore existential questions that affect the domestic everyday. Malick’s modern style – Emmanuel Lubezki’s swooping cameras drenched in earnest narration – isn’t for everyone, yet it is the perfect vessel for the director’s unique, philosophical perspective. Praised as undiluted genius upon release, time (and an increase in Malick’s once sparse output) has diminished The Tree of Life’s mystique, but for those willing to revisit its charms on the big screen, it remains one of the 2010s defining works.

- Jury president: Robert De Niro

- Also in competition: Midnight in Paris

Every Terrence Malick Film Ranked

17. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (Jacques Demy, 1964)

After years of flirting with the format, French New Wave legend Jacques Demy dove head first into the world of movie musicals with The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. As the separated lovers unite and unravel in the titular city, Michel Legrand’s compositions imbue each scene with the melodic wonder of a swooning torch song. Of all the Palme d’Or winners, this is perhaps the greatest crowd-pleaser – a truly irresistible song-and-dance sensation to which my feeble words can hardly do justice.

- Jury President: Fritz Lang

- Also in competition: The Woman in the Dunes

16. Shoplifters (2018, Hirokazu Kore-eda)

Triumphing over the stiff competition in 2018, Shoplifters is the culmination of Hirokazu Kore-eda’s career-long fixation with the eccentric machinations of family life. The film traces a makeshift quintet of characters on Tokyo’s economic outskirts as they overcome the moral and practical obstacles of their lifestyle in which they shoplift to get food on the table – the point being that family is not something bound to biology or genetics. Told with elegance and understated empathy, the film harmonizes Kore-eda’s strengths to create something thought-provoking and tear-inducing in equal measure, it’s little surprise that it became Japan’s first Palme d’Or winner in twenty years.

- Jury president: Cate Blanchett

- Also in competition: Burning

Also Read: All Hirokazu Kore-eda Films Ranked

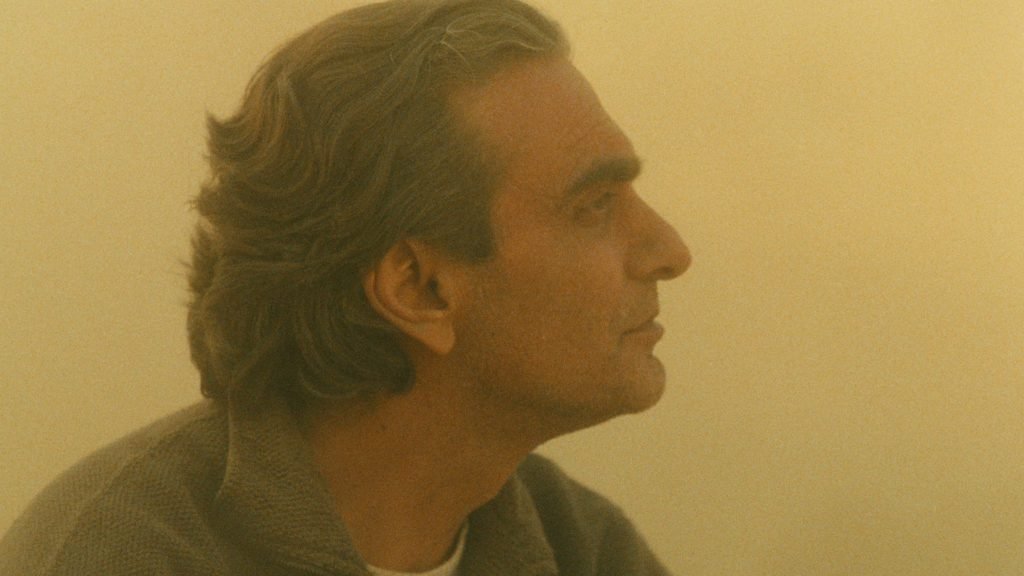

15. Taste of Cherry (1997, Abbas Kiarostami)

Drive, talk, drive, talk again, drive again – Taste of Cherry is a drama whose raw emotional impact is achieved through ruthlessly elemental storytelling. There’s a tragedy in the bluntness of Mr. Badii’s (Homayoun Ershadi) quest for burial and rewarding beauty in the conversations that either prevent or hasten his suicide, depending on your interpretation. Cannes veteran Abbas Kiarostami leaves the ending deliberately ambiguous, eschewing cliché in favor of a typical deconstructionist approach, as we see the director and his colleagues with camcorders following Ershadi, not Mr. Badii anymore, around. It’s everything that was so compelling about the Iranian New Wave distilled into a hundred minutes.

- Jury president: Isabelle Adjani

- Also in competition: The Sweet Hereafter

14. I, Daniel Blake (2016, Ken Loach)

Ken Loach’s style hasn’t changed much since his days as the leading light of British kitchen sink realism in the 1960s; then again, the issues affecting the working class from indifferent state apparatus haven’t changed much either. The focus has shifted slightly; whilst Cathy Come Home was a direct plea for increased housing after the war, I, Daniel Blake takes aim at modern Conservative Party austerity through its story of a laborer trying to get back into employment after a bout of ill health, but Loach’s empathetic touch, able to examine those in poverty without gazing or glamourizing their suffering, is seemingly eternal.

- Jury president: George Miller

- Also in competition: The Handmaiden

Also Read: 10 Best Films of Ken Loach

13. Viridiana (1961, Luis Buñuel)

Anchored by powerhouse performances from Silvia Pinal and Fernando Rey, Viridiana is one of Luis Buñuel’s most enduring masterpieces. The director, a committed atheist, eschews the didacticism of other films focusing on religious repression of the mind and instead creates a film defined by dark comedy and a clear-eyed admiration of the good in humanity beyond the self-declared piety of the organized church. Viridiana speaks of an artist at crossroads between his surrealist and social realist sensibilities, creating something quite beguiling as a result.

- Jury president: Jean Giono

- Also in competition: Mother Joan of Angels

12. Elephant (2003, Gus Van Sant)

Gus Van Sant’s chilling drama, inspired by the Columbine high school massacre, isn’t to everybody’s tastes – it’s cryptic storytelling and minimalist aesthetics continue to divide opinion. But those with the patience to buy into Elephant’s central structural conceit will rediscover a work brimming with human empathy and compassion. Van Sant became just the second director to win both Best Director and the Palme d’Or for the same film; considering the tasteful way in which he handled his film’s touchy subject matter and a plethora of non-professional actors, it’s hard to argue it was the wrong decision. One of the 21st century’s defining features.

- Jury president: Patric Chéreau

- Also in competition: Dogville

11. Parasite (2019, Bong Joon-ho)

2019 offered Cannes its greatest window of relevancy in years as Parasite won not just the Palme d’Or but became the first foreign-language film to win the Oscar for Best Picture. Considering how cleverly director Bong balances the genre trappings of his quasi-home invasion thriller and his sharp political commentary, it’s little wonder why its appeal was so universal. Formally excellent with glossy montages and set pieces and embellished by fantastic performances, it’s not long before Bong’s greatest film enters the canon, as it has already engaged legions of fans in uncharted waters of foreign film.

- Jury president: Alejandro González Ińárritu

- Also in competition: Portrait of a Lady on Fire

Also Read: All Bong Joon-ho Movies Ranked

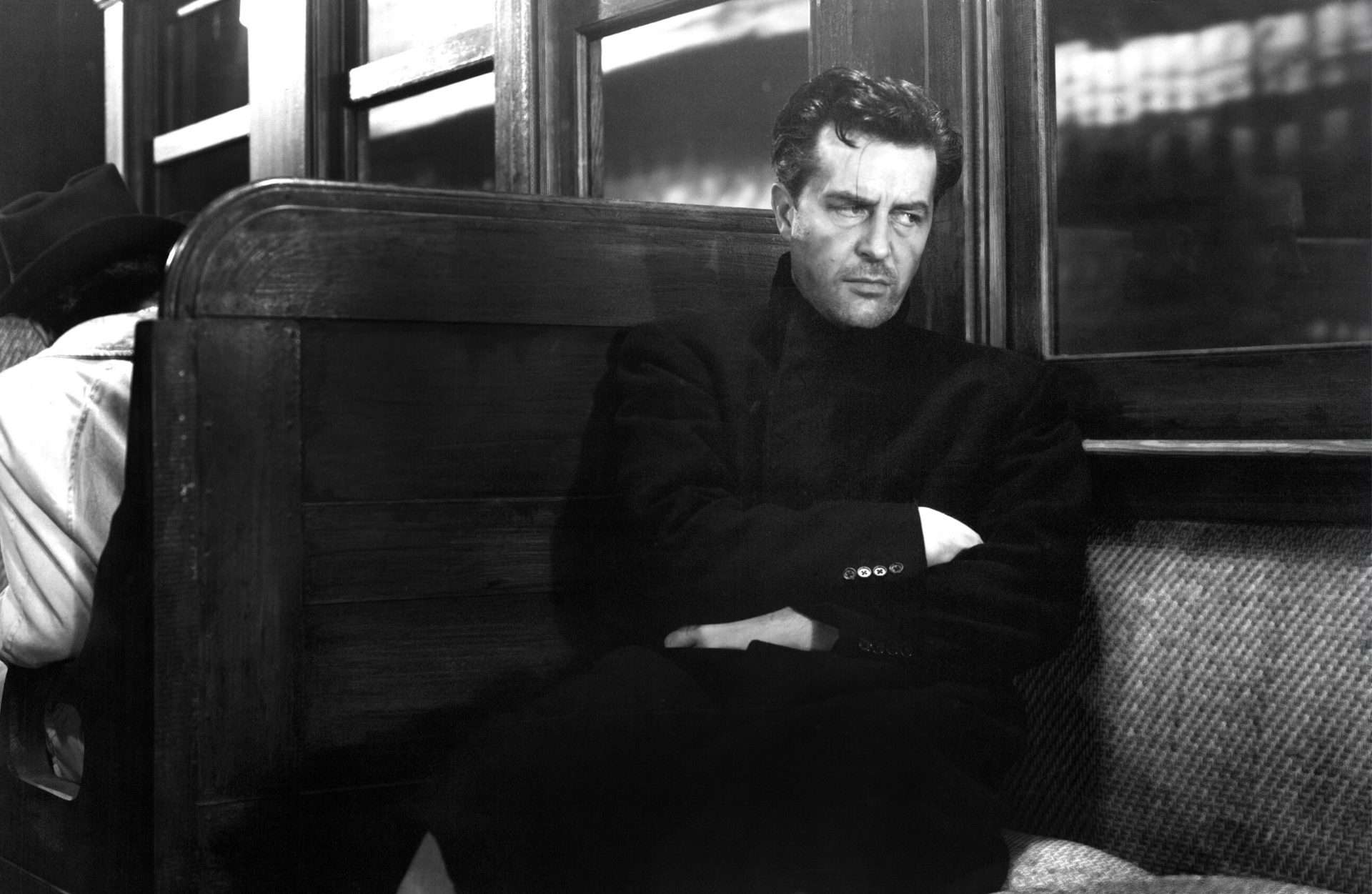

10. Othello (1951, Orson Welles)

Welles consolidates his status as cinema’s greatest Shakespearean with this dynamic adaptation of Othello, which chops and splices the text to create a film of simmering tension. That tension is reflected in the famously torturous process behind the scenes, in which Welles abandoned Hollywood for the hills of Tuscany for three-year labor of love that has since been recut and restored countless times – in fact, the version of the film that won the Palme d’Or in 1952 is only available on French VHS nowadays. The European theatrical cut, a lean 93 minutes, is the greatest incarnation of the auteur’s vision, thoroughly exploring the racial tensions at the heart of the source – albeit an exploration that may to modern viewers seem undercut by Welles’ use of blackface for the title role. Enduring beyond the sensitivities of time is the blistering display of technique from a master filmmaker in his element with a visible, infectious passion for the genius of its source; the centuries-old texts of Shakespeare have never felt more urgent or involving on the silver screen.

- Jury president: Maurice Genevoix

- Also in competition: Umberto D.

9. The Cranes Are Flying (1957, Mikhail Kalatozov)

Though even the most ardent of Soviet cinephiles are only privy to a small selection of his work, based on the form of his three masterpieces, Mikhail Kalatozov can lay claim to being one of the most inventive and talented visual storytellers of his day. Together with DP Sergei Urusevksy, Kalatozov uses his camera to glide around its subjects, rendering The Cranes Are Flying arguably the ultimate embodiment of Soviet wartime spirit, as the freneticism of desire to defend one’s country is contrasted with the emotional devastation it can leave behind. The director wisely eschews the borderline fetishization of hardship present in later communist war films in favor of something more nuanced and therefore moving – the extent of a soldier’s patriotic sacrifice as shown through the living hell of false hope and endless tension faced by his relatives.

- Jury president: Marcel Achard

- Also in competition: Mon Oncle

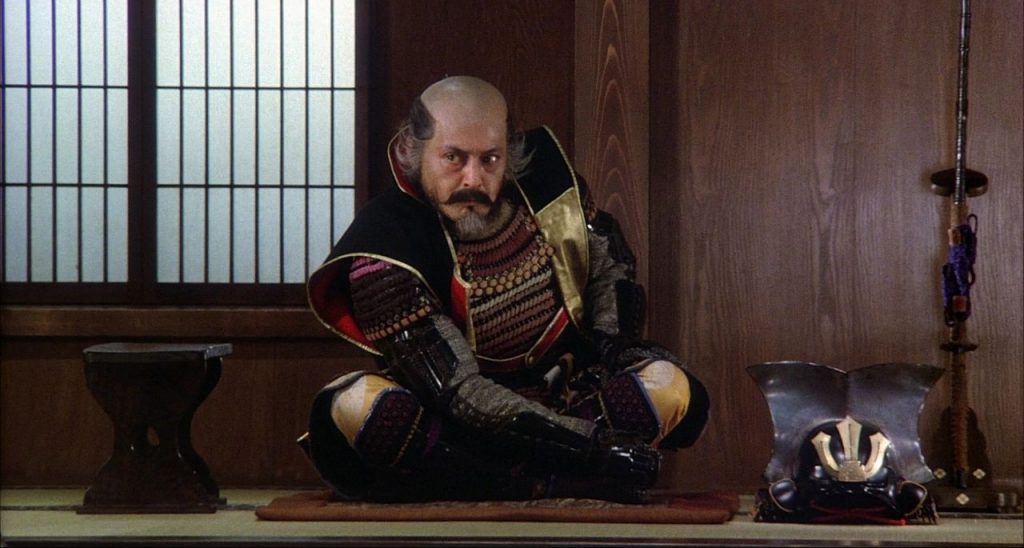

8. Kagemusha (1980, Akira Kurosawa)

Joint winner with Bob Fosse’s visionary self-eulogy All That Jazz in a particularly strong year on the Riviera, Kagemusha sees a master of monochrome finding his feet with color, treating the frame as his canvas on which he will paint with meticulous detail and unbridled enthusiasm. From its opening multiple-minute stationary take, the film has deliberate pacing but not at the expense of the suspense and drama seen in Kurosawa’s classic ‘jidaigeki’ of the 1950s. However, there is certainly a renewed patience in his storytelling. Further dimensions are added by Tatsuya Nakadai’s earth-shaking performance, convening the confusion and horror of a man trapped in a life of torturous duplicity. Tender moments between him and his faux-offspring are particularly poignant, a genuine human relationship forged and then torn apart by the indifferent machinery of feudal war. Breathtakingly beautiful and, like much of Kurosawa’s later work, subtly devastating.

- Jury president: Kirk Douglas

- Also in competition: Every Man for Himself

100 Films Recommended By Japanese Master Filmmaker Akira Kurosawa

7. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010, Apichatpong Weerasethakul)

Apichatpong Weerasethakul arrived at Cannes in 2010 as a promising young auteur, yet still one primarily known for the novelty of his name, and left as the leading light of global cinema with his fantastical tale of loss and reincarnation. It’s suitable that Tim Burton, another filmmaker who excels in enigmatic world-building, was jury president to award the brilliant Uncle Boonmee, but whilst Burton’s universes are squarely fixed in German and American iconography, Weerasethakul seems to be working on some sort of astral plane. Words simply do not suffice to detail the magic of a work that is so poetic and experimental, though never impenetrably so, as the filmmaker maintains his understanding of human emotion and interaction. With a lasting impact bolstered by one of cinema’s greatest-ever needle drops, there’s still nothing like it.

- Jury president: Tim Burton

- Also in competition: Certified Copy

6. Secrets & Lies (1996, Mike Leigh)

Mandatory Credit: Photo by Moviestore/Shutterstock (1616157a)

Secrets And Lies (Secrets & Lies), Marianne Jean-baptiste, Brenda Blethyn

Film and Television

“Why can’t we share our pain?” questions Maurice (Timothy Spall) at the climax of Mike Leigh’s greatest film, an exacerbated request for emotional honesty in a family unit crumbling under the weight of various internal and external factors. It feels a fitting mantra for Secrets & Lies, in which both the titular vices combine to break the viewer’s heart, and then repair it, with a life-affirming coda. Whether its Spall’s heartfelt sincerity, Brenda Blethyn’s hysterical wailing, or Marianne Jean-Baptiste’s restrained heartbreak, Secrets & Lies contains, put simply, some of the greatest performances to ever grace the silver screen, the awe-inspiring result of months of rehearsal work from director and cast which renders each scene more emotionally authentic than the last. Meanwhile, the intricacies in dynamics present in the shadow of a screenplay cement Leigh’s credentials as one of modern cinema’s great dramatists. Prepare to be swept off your feet – but remember to bring some tissues.

- Jury president: Francis Ford Coppola

- Also in competition: Fargo

Also Read: 10 Essential Mike Leigh Films You Should Watch

5. Blow-Up (1966, Michelangelo Antonioni)

Thanks in part to the distribution of Carlo Ponti, Blow-Up was a major international hit upon its release in 1966, garnering several Oscar nominations as well as the Palme d’Or and bringing the ingenious mind of Michelangelo Antonioni to the mainstream. In hindsight, this seems bizarre. Despite the film’s commercial success, it deviates little from the austere arthouse of the director’s previous films. However, in his first time working outside of Italy, Antonioni’s work receives a new dimension through the cool distance he is able from the culture of 1960s Britain. Whilst in some ways Blow-Up is the living chronicle of London’s heyday, it can also feel as if Antonioni is already prophesying the movement’s inevitable burnout through a parade of aimless characters and cheap sex. Still brilliant, prophetic, and with an eerie atmosphere all its own.

- Jury president: Alessandro Blasetti

- Also in competition: Mouchette

4. All That Jazz (1980, Bob Fosse)

An electrifying demonstration of artistic skill and personal fortitude, All That Jazz is one of the supreme achievements of American cinema. In a Hollywood climate that seems fixated on constant “reinvention” of the musical, it’s always a great time to revisit one of the genre’s masters, Bob Fosse, who relays his tale of self-abuse and personal demons with filmmaking that so masterfully imbues song-and-dance within the darkest of frameworks. The choreographer-cum-director demonstrates impeccable craft in his second language of cinema, montage, and sound design in particular. As Fosse’s alter ego Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider) greets himself in the mirror each morning with an increasingly beleaguered “It’s showtime folks!” the exacerbating mechanics of Broadway become apparent to the viewer. His pain becomes our pain in this universe of neon lights and stubbed-out cigarettes. The movie was, in no small part, inspired by Fosse’s own brush with death years prior, and the fact that he would pass away less than a decade later adds further potency to his greatest film.

- Jury president: Kirk Douglas

- Also in competition: Being There

3. Apocalypse Now (1979, Francis Ford Coppola)

Few films in the canon have as much mythology surrounding them as Apocalypse Now, a film that almost killed its director in a months-long voyage in the jungle whilst filming, one not dissimilar from the journey embarked on by tortured soldier Benjamin Willard in this ingenious reimagining of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Even more, overplayed is the praise of how the film so effectively captures the chaotic fervor of the war in Vietnam, but it’s undeniably the truth, as Coppola successfully makes a thrilling war picture that never descends into depicting conflict as an amusement park. The strongest praise is perhaps reserved for cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, whose vision of the sun-baked jungle defines not just this masterpiece but the collective cultural image of Vietnam in the West. Coppola’s best film, and boy, is that saying something.

- Jury president: François Sagan

- Also in competition: The Tin Drum

40 Years of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now

2. Underground (1995, Emir Kusturica)

In 1995 Emir Kusturica joined a select group of filmmakers to have won the Palme d’Or twice, but his unhinged send-off to the former Yugoslavia, Underground, seems to have been forgotten by the masses over time. Nevertheless, it remains one of cinema’s most exhibitory experiences, a singularly propulsive act of tribute and critique to a homeland left behind. To those in the know, it has never lost its relevance; its fingerprints are still seen everywhere in modern cinema. It’s not hard to draw a link between the sprawling historical framework of Kusturica’s masterpiece and the recent work of Quentin Tarantino, nor would its surrealist tendencies upset fans of Jean-Pierre Jeunet. Underground, however, remains something entirely unique and unmatched in the subsequent work of its director. Considering its historical context and swaggering style, it may be the most vital film of the 1990s.

- Jury president: Jeanne Moreau

- Also in competition: La Haine

1. La Dolce Vita (1960, Federico Fellini)

Its name evokes a million images, its poster is draped across millions of bedrooms, and its Trevi Fountain showpiece is the very definition of iconic. How did a three-hour Italian art film about the malaise of celebrity culture become an emblem for not just world cinema (as Italy and France arrived in America through the silver screen in the early 1960s), but for the era it represents? The sights and sounds of Rome cultivated by Fellini in his greatest film continue to inform visions of the vacuity of fame and the beauty of the ‘Eternal City’, and Marcello Mastroianni and Anita Ekberg remain dazzling in their star power. Watching La Dolce Vita in 2022, it’s impossible to remove the film from its cultural impact and the acclaim heaped on it by countless critics over six decades, but it does not affect one iota’s enjoyment of the film, which remains a contemporary, thrilling watch. No film has ever better embodied the ethos of Cannes, to elevate the art of cinema to a higher, more visible level. Without La Dolce Vita, the world of cinema is unimaginably drearier.

- Jury president: Georges Simenon

- Also in competition: L’avventura