A superhero thriller without the hyper-stylized energy or the textbook hero-villain framework, M. Night Shyamalan’s “Unbreakable” quietly kicked off what would later become the Unbreakable film series. Originally written as a spec script and structured like a comic book, the film never really cares to follow the line between studio-safe genre and stubborn realism. It just does its own thing and ends up finding a voice that feels oddly singular.

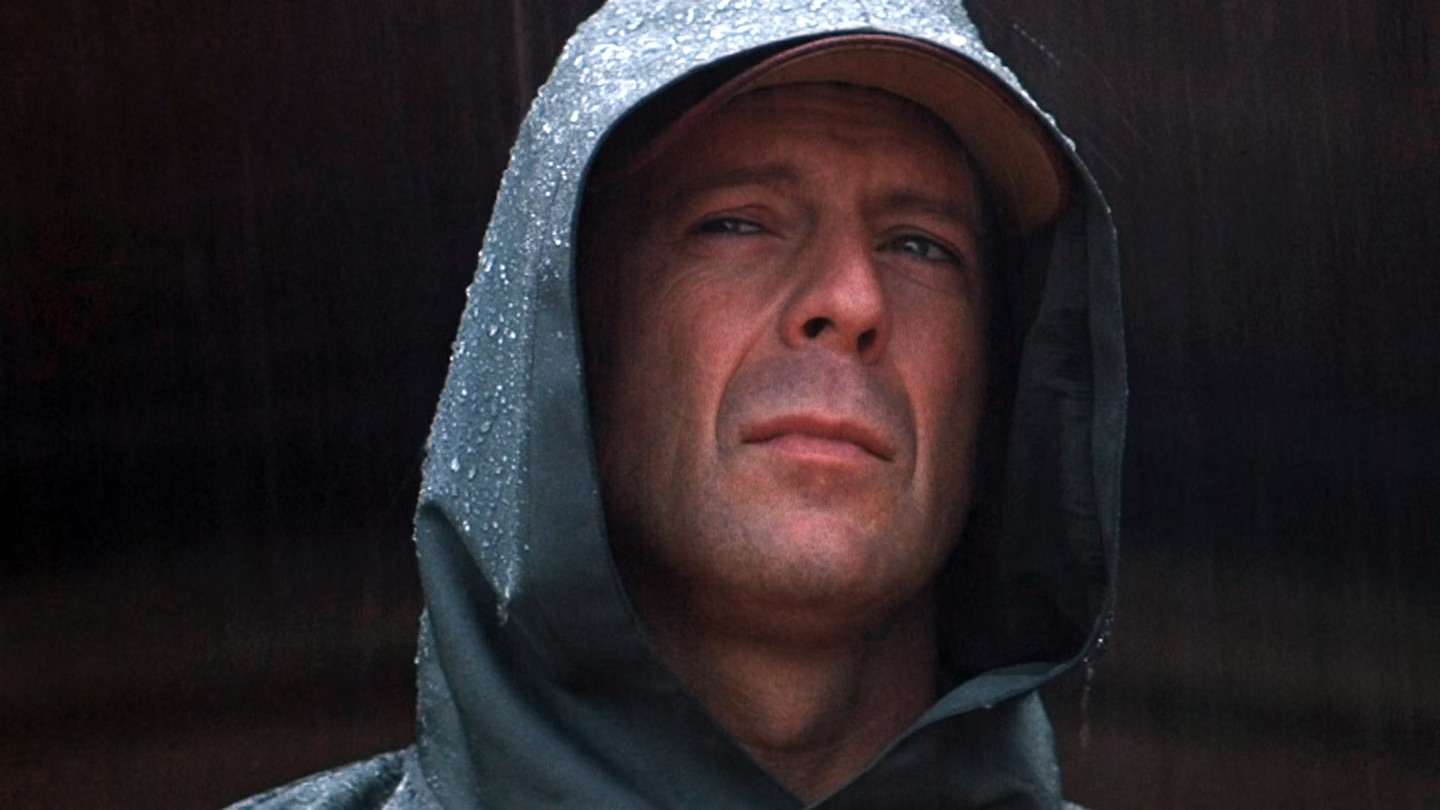

Starring Bruce Willis and Samuel L. Jackson in performances that strangely mirror each other, the film roots both its superhero and supervillain origin arcs in something so grounded, you stop watching it for patterns or genre cues and start watching for what’s actually happening. There’s a kind of lived-in grit to the storytelling—like domestic drama that just happens to brush against the supernatural. And somehow, without even trying too hard, the film builds this moody, almost indie texture without ditching its mainstream footing.

What “Unbreakable” does best, though, is redefine what it means to feel safe. It frames security as this weirdly personal, almost spiritual thing—what makes one person feel whole could destroy another. It’s not about saving the world. It’s about surviving yourself. And since the bulk of the film hangs out with a regular American guy going through a dead marriage and unresolved daddy baggage, the gloomy tone never feels like a gimmick. It fits. There’s no need to fight the comic-book shape of the story, because it barely wears that shape to begin with.

Also, not everyone in this film is Elijah Price. Some characters—like the audience—are just trying to figure out what the hell’s going on. And that’s part of the tension, too. This isn’t the kind of movie that lays things out neatly. If you’re half-tuned in, it might feel like a code you’re not cracking.

So, here we are trying to decode it.

Unbreakable (2000) Plot Summary and Movie Synopsis:

Opening with statistics on comic book production patterns and consumption habits in the US, we are transported to 1961 Philadelphia, where a crowd has gathered around a mother with a newborn. The doctor, upon taking the baby into his arms, is shocked. He turns to the delivery nurse and asks if she dropped the child—an accusation that horrifies her. She denies it outright. The doctor then urgently calls for an ambulance, saying the boy has sustained multiple fractures in the womb—his arms and legs are broken.

What strange event changes David Dunn’s life forever?

In the present day, a weary man named David Dunn is returning from a job interview in New York to Philadelphia on the Eastrail 177 train. Spotting a beautiful sports agent named Kelly seated beside him, he quickly slips off his wedding ring and tries to flirt. Kelly shuts him down, telling him she’s married and moves to another seat. Suddenly, David senses the train speeding up. Hours later, he wakes up in a hospital room. A routine inquiry follows. When he asks the doctor why he looks so stunned, he learns he’s the sole survivor of a derailment that killed all 131 other passengers. His wife Audrey and son arrive at the hospital. Audrey asks if he got the job—David shakes his head.

Who reaches out to David, and why?

David attends a memorial service for the crash victims. Afterward, he finds a note on his car asking, “How long has it been since you’ve been ill?” and inviting him to Limited Edition, an art gallery. Back home, David anxiously asks Audrey if she remembers him ever falling sick. She says she doesn’t, but adds it might just be her exhaustion talking.

What childhood trauma shapes Elijah’s worldview?

The film then flashes back to 1974. A young Elijah sits in his room, staring despondently at a turned-off TV. He tells his mother he doesn’t want to go back to school because kids call him “Mr. Glass”—they say he breaks like glass. In response, his mother gives him a challenge: she leaves a comic book on a bench in the local park and tells him he’ll have to go and retrieve it himself before someone else takes it. Elijah grows up to build Limited Edition, an art gallery showcasing comic book illustrations.

How does David begin to question his own past?

David visits the gallery with his son Joseph to meet Elijah. Elijah lays out his theory of real-life superheroes. He explains how pictorial storytelling has preserved history across the ages, and argues that if his own condition represents extreme physical fragility, then someone at the opposite end of the spectrum—someone unbreakable—must also exist.

He concedes, however, that this is only a theory, full of its own holes. David gets uncomfortable, suspects it’s a scam, and leaves. That night, he searches through old newspaper clippings from his days as a star quarterback, looking for reports of the car accident he had in college. Audrey knocks on the door and asks if he’s been seeing other women, given the strains in their marriage. David denies it. Audrey breaks down and says she wants to give their relationship another chance—his survival feels like a sign.

When does David start to show signs of something more?

Later, Elijah visits David at the football stadium where he works as a security guard. He starts asking pointed questions, like why David chose a job that involves protecting people. When David notices a man in a camouflage jacket and correctly senses he’s a junkie carrying a gun, Elijah is intrigued. How did he know? As Elijah keeps pressing, David gets irritated and tells him to either sit down or leave. Elijah follows the junkie, but while pursuing him, falls down a staircase and fractures his ribs, arms, and most severely, his right leg.

Audrey is assigned as his physical therapist. During one session, Elijah asks her about how she and David met. Audrey confesses that if David had become a football star, they probably wouldn’t have been together, because football represents violence, something she deeply resents. When Elijah jokingly asks if things got better after the car accident, she replies, “Sort of.” Elijah then reveals he’s met David and begins sharing the same theory with her.

David picks Joseph up from football practice and tells him he’s going to work out. Joseph tags along to help. As David bench presses, Joseph keeps piling on weight. To David’s own amazement, he successfully lifts 350 pounds. Joseph starts idolizing him, believing he’s a real superhero. One day, Joseph gets into a fight at school. When David comes to pick him up, the principal reveals that she once rescued him from a drowning incident—he had been unconscious underwater for five minutes and developed pneumonia.

She gently asks if he still fears water. That night, Audrey tells David about her session with Elijah and expresses sadness over how trauma can twist people’s beliefs. Then, in an intense moment, Joseph aims a gun at his father, desperate to prove Elijah’s theory. David sternly disarms him and unloads the bullets. The next day, he confronts Elijah and tells him to stop. He cites his childhood trauma—nearly drowning—as proof he isn’t unbreakable.

Also Read: 35 Best Comic Book Movies of All Time

That night, Audrey and David go on a “first date” to rekindle their relationship. It goes well. When they return home, the babysitter tells them someone called from New York—David got the job. Audrey is saddened, as this might slow their emotional healing. Soon after, Elijah calls and says that even superheroes have weaknesses—David’s, he argues, is water. David then remembers the car accident—how he was unharmed and even ripped open the car door to save Audrey. He had faked the injury to quit football because Audrey hated the sport. He calls Elijah and asks, “What now?” Elijah tells him to go public.

Unbreakable (2000) Movie Ending Explained:

How does David discover the extent of his powers?

David realizes that his intuition at work may actually be extrasensory perception. By consciously honing it, he discovers that touch gives him visions of people’s past crimes. As he walks through crowds, he sees theft, assault, and rape through mere contact. Eventually, he spots a janitor who has broken into a family’s home, killed the father, and is holding the mother and children hostage. David follows him. At the house, he frees the children but is pushed into a swimming pool. Unable to swim, he nearly drowns—his one true vulnerability. The children pull him out. He then strangles the janitor to death, but finds the mother already murdered.

What is the final revelation between David and Elijah?

The next morning, David quietly shows Joseph a newspaper sketch of the mysterious hero. Joseph recognizes his father and tearfully promises to keep his secret. At an exhibition at Limited Edition, David meets Elijah’s mother, who explains the difference between villains who fight with brute force (soldier villains) and those who use intellect (archnemeses). Elijah then asks David to shake his hand, and in that moment, David sees the truth.

Elijah orchestrated multiple high-profile accidents, including the train crash, all to find his counterpart: a superhero. Moreover, Elijah finally declares, “Now that we know who you are, I know who I am.” He adopts his childhood nickname, Mr. Glass, as his villainous identity. Post-script text reveals that David reported him to the authorities. Elijah is now confined to a psychiatric hospital for the criminally insane.

Unbreakable (2000) Movie Themes Analyzed:

The Fear of Becoming Who You Are

Through the character of David Dunn, M. Night Shyamalan explores a far subtler and lonelier kind of depression. The film initially treats David’s reaction to his supernatural condition as mere fascination. But as the story deepens, that fascination reveals itself to be a smokescreen. David isn’t afraid of being hurt—there’s not much in this world that can hurt him. What truly scares him is being seen. To be noticed is to risk being known, and for a man like David, that’s far more terrifying than bullets or fire.

His everyman-ness isn’t incidental—it’s compulsive. He clings to ordinariness like it’s armor. He doesn’t want to feel unique, look unique, or sound like someone who matters. His strength isolates him. Beneath that strength is the aching fear that he’s drifting alone, cut off from the world in ways he can’t articulate.

The film, with its deliberately cramped and quiet structure, peels back this condition gently. We’re made to notice how people bury their truths, not just to avoid pain but to endure the dull ache of existence. And those truths are often tied to some form of dormant excellence. David gives up football. He lies to his wife about cheating, not out of malice but out of a deep fear of being real. He whispers about $40 raises like he’s apologizing for wanting anything at all.

In contrast, Elijah’s character is the other extreme. Some people are so certain of their truth, so consumed by it that the rest of the world begins to look unworthy by comparison. Elijah builds an entire empire around his truth, but it’s a fragile, extremist kind of clarity. His quest for meaning becomes militant. He isn’t a villain because he’s wrong—he’s a villain because he weaponizes being right.

The conflict here isn’t hero vs. villain—it’s repressed potential vs. overexposed obsession. Even the awakening is quiet, almost tragic. When David finally tells Joseph that he was right all along, it’s not a moment of triumph. David looks exhausted. Joseph looks drained. Belief, it seems, is a tiring thing to hold onto.

Comic Books as Modern Mythology

There’s long been noise around whether comic book cinema is unserious—“amusement park rides,” as Scorsese once said. But the deeper question is this: what does serious comic-book storytelling even look like? Unbreakable doesn’t answer that—it barely tries. Instead, it sits in that space between lore and loneliness. It gives the superhero a traditional arc, but it lets the villain’s origin unfold first, reordering the mythology in a way that catches you off guard.

Elijah is a dangerous kind of oracle. His wisdom doesn’t come from trauma alone—it’s born from the hypersensitivity bred by physical frailty. The body, in this world, becomes prophecy. The film treats physicality the way comics treat illustration: detailed, dramatic, and definitive. Text—nuance, psychology, contradiction—is secondary. Elijah’s obsession with balance, with purpose, feels like a theological argument disguised as a fanboy rant. What’s fascinating is how easily we buy into his logic, even as it turns monstrous. The film is less concerned with whether comic books are real myths and more curious about what kind of people need them to be.