Cinema is an integral part of a state’s ideological apparatus, which today in the 21st century stands taller than its counterparts. When an artist, whose existence is determined by the relations of production, translates his imagination into sound and images, it takes the form of something which can roughly be called cinema and reflects a collective’s or an individual’s relations with the state.

With every passing political shift – which inevitably changes the base and affects the superstructure inexorably, cinema, like its counterparts, suffers the dread of becoming dated. Rarity occurs when a film transcends the materialistic changes of a society, which naturally differs from the time when it was produced. Satyajit Ray’s “Nayak” (1966) belongs to such a rare pedigree. Its re-release in theatres, in a 2K restored print, is nothing less than a political event which invites us to read this classic which still competently corresponds to the present dialectics of our society.

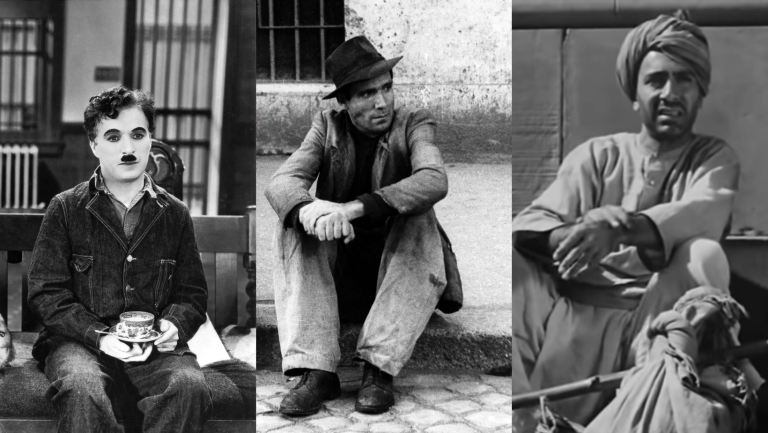

Ranging from Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay to Henrik Ibsen, Ray’s oeuvre mostly stands upon literary adaptations, while “Nayak” is one of the few stories that Ray penned himself to adapt into celluloid. It peeks into the convoluted intra-terrain of the matinee idol, Arindam Mukherjee (played by Uttam Kumar). Ray posits Arindam in the nucleus of his story and curates the orbit with a handful of characters, satelliting around him. While Arindam’s topographical inner view illustrates his victimization at the hands of merciless commodification, characters other than him represent a space where a duel between humane moral values and mercantilization of body and soul takes place.

At the summit of his career, Arindam has started realizing that his exclusive presence in films has ceased to lure the audience to the theatres. He decides at the last moment to accept a government award in Delhi and boards a train, with sleeping pills and liquor as his reliable companions.

Deploying train as a philosophical backdrop against the multifaceted odysseys of characters has been a stylistic trait that Ray has mastered over the course of his career. In “Nayak”, Ray places Arindam’s inner-journey inside a train. The protagonist’s introspection finds its way out at times passively through surrealistic haunting dreams and sometimes actively through his penance-like confessions. This drainage of Arindam’s piled-up traumatic baggage sheds his glamour-façade and invites us to sneak under his skin to realize and locate a commodified individual (film-star) and his loneliness in a ruthless cosmopolis dictated by capitalism.

While inside the train, an opportunist advertisement merchant (Kamu Mukhopadhyay) tries to coax his superior in business with the filthy idea of offering his wife’s somatic presence as a sexual commodity to secure a deal, other passengers in the train dimly gossip about Arindam’s latest rumor of being involved in a bar-brawl. Although much familiar with the fawning adoration of the masses, Arindam mostly bypasses his co-passengers, selectively speaking only to those who don’t really care about his vocation by hiding his eyes with black goggles and consuming sedatives.

Two dreams that Arindam witnesses during his journey, metamorphose his early taciturnity into confessions. In the first dream, he encounters his itinerary to fame and money. Ray constructs the first dreamscape in a surrealistic, almost tableaux-like fashion, where Arindam finds himself drowning in the quicksand of money, amid skeletons holding telephone receivers and Shankar da (Somen Bose), who had alleged Arindam – before his break into the films – for intending to sabotage his theatre, watching him sink.

The second dream unveils Arindam’s guilt of refusing Promila (Sumita Sanyal), an actress, to cast her as his co-actress, deceiving his friend Biresh (Premangshu Bose) in front of a factory workers’ strike and partaking in a bar-brawl that has been published in newspapers lately. In the aftermath of these dreams, he runs into Aditi (Sharmila Tagore), his co-passenger, who runs a women’s magazine called “Adhunika” – to confess the guilt that’s eating him from inside.

Ray, through Arindam’s repentance, poses the question: “Who is a hero?”, and draws a semblance between Arindam’s fame and loneliness.

The Hero is someone who has gained money and fame at the expense of commodifying himself to cater to his audience; thereby erasing his human(e) identity from the society. He is not allowed to break free from his class shackles; hence, Arindam admits to Aditi: “It’s not good for us to talk too much. We live in a world of shadows, so it’s best not to show the public too much of our flesh and blood.” A Hero is someone for whom conquering the box office is inversely proportionate to conquering his own loneliness; in a typical Subrata Mitra-esque close-up, Arindam points to his heart and blurts out to Aditi: “It’s all piled up in here. There’s nobody I can tell it all to.”

Arindam’s confessions could have been a treat to his followers as well as critics, but Aditi saves him by tearing off the notes she had taken from his confessions to publish in her magazine – an act of humanism, identical to Ray’s film-philosophy. This constant duel between rapaciousness and humanity, commodification and human existence makes “Nayak” a relevant film even today.

It is Ray himself who admitted that he had Uttam Kumar in his mind while writing the screenplay of “Nayak.” Then, would it be wrong to say that casting Uttam Kumar in “Nayak” was a political praxis for Ray? After all, who else in the Bengali film industry, back then, would have felt a personal connection with ‘Nayak’s script, if not Uttam Kumar?