Interview by Mariam Liperteliani

“A man who lies to himself, and believes his own lies, becomes unable to recognize truth, either in himself or in anyone else, and he ends up losing respect for himself and for others.”

The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky

The third edition of the Kutaisi International Short Film Festival was characterized by diversity. The program was structured subtly, and the versatility of the films filled the international audience with compelling emotions.

The Georgian section was profound, critical, and political as simultaneously the Georgian film fund is plundered by heinous authorities, which tend to persuade the local audience, that the organization needs to be reorganized urgently, that corruption is empowered, and the appreciated films represent preposterous lies. For them, contradictory, precarious, contemplative, and consequently, political films are unacceptable, and more than 400 workers from that field strive to regain the independence of the Georgian cinema, which was obtained at the cost of hard labor after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

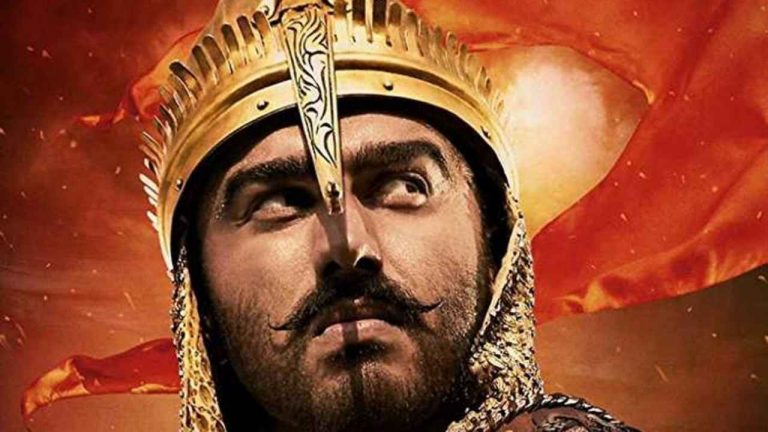

Ascension was one of the selected films. It is important to mention that the director of this picture, Giorgi Tavartkiladze is in prevalent protest and has announced a boycott of the reorganization of the film fund. The story deals with a young broadcaster who creates content for a specific segment of society whose attitude towards religion is excessive. Their grasp of reality slowly evaporates, and the prevalent bigotry leads them to place the chosen messiah on the verge of suicide.

Personally, I perceived the picture as a bold opposition towards the authorities, who tend to enlarge their prosperity at the cost of an abasement of the easily deceivable, uneducated swarm, but the directorial view would be more precise and promising. I have had an opportunity to elaborate on this feisty short film with the director himself.

Here is a little extract from our conversation.

Mariam: First, thank you, Giorgi, for your time. I would like to express my gratitude for your feistiness that you could unravel and explore the concept of religious bigotry in our country. My first question is also related to that. What was your main inspiration to elaborate on this sensitive topic, and were you afraid of aggressive reactions as an outcome?

Giorgi Tavartkiladze: Religious bigotry is permanently provoked in society intentionally. It cannot be prawned out of thin air. Humans tend to be subservient, and finding the shepherd becomes obsolete. This obsession needs some fuel, which is provided by authorities, whose priority is to enlarge obtained prosperity, without hard toil. Uneducated parts of society can be easily pleased and frauded.

Apart from that, the seeking process for the shepherd is tantalizing, and the only shelter could be found under the roof of delusional safety. For me, Georgian people strive to find a reified God because of the Soviet Union. After the dissolution of this treacherous organism, our little country regained its independence, which forced us to cope with slovenliness without the shepherd. The tendency of being subdued is entrenched in the subconscious, and religious bigotry emerged as a substitute.

The hypocrisy of clerical authorities unfortunately stays behind the veil, and the exhilaration induced by compelling, undeciphered faith is used for destructive actions. During the working process, it occurred to me that if the chosen Messiah confessed to the parish that he was delusional, mistaken, and the sanctuary was not really the dwelling of God, the swarm would react very aggressively; they would tear him apart and create holy parts out of his savagely demolished body.

That is when I realized I wanted to portray the shepherd of a cult not as an oppressor but as a victim. As for the second question, every cinematic experience includes the terror of being judged, criticized, or even disgraced, so as a director, I have embraced the fact that during the working process and even at the end of it, the consequences are oblivious for us.

Mariam: The main character Antimoz has some mysterious qualities. He lives with his parents, and this deficiency of personal space somehow determines his urge to be subservient, or maybe he needs gratification from the authorities. Even his tidiness and courageous nature portray a gullible person’s image. How did you construct this character? Tell us a bit more about his background because it is obscure, and when did you decide to give this role to Jano Izoria, who plays the main character, Antimoz?

Giorgi Tavartkiladze: Antimoz was the only child, often flattered and overly praised by his parents. This distorted perception from his acquaintances spawned and blossomed in his subconscious, and in adolescence, when his disordered beliefs collided with reality, the only way of preserving this imaginary immaculateness was to fully integrate into the cult, where he would receive the gratification for being obedient and subdued.

On the other hand, Antimoz has a persistent, abstinent nature, he is aware of technologies, and he knows how to record, edit, apply, and spread information which makes him the best candidate for the broadcaster Eldar sought. I suppose the main pattern with Antimoz is that his ambitions are higher than he is capable of, which triggers the destruction he goes through. As for the second part of the question, I have worked with Jano on several occasions, and the versatility of his nature inspired me to create such an ambivalent, mysterious character whose insidious landscape needs deep contemplation to dismantle.

Mariam: The scenery gets quite tragic when the remnants of the Messiah are discovered. The sound emerges as an accurate embellishment of the images depicted on screen. How do you explain the continuous usage of ominous, even hazardous, sounds in that sequence of scenes?

Giorgi Tavartkiladze: The sound represents Antimoz’s spiritual ascension. The discernment of reality is being restored, but now he is obliged to eradicate previous beliefs that were patched on him. The cleanse is painful but necessary.

Mariam: And lastly, if it is not a secret, do you intend to make a full-length film out of this story? Because Antimoz’s character has so many layers that must be unfolded. The ending left me with an urge to discover Antimoz’s discreet landscape, which is unobtrusive even for him.

Giorgi Tavartkiladze: Antimoz intrigues the audience, and observance deteriorates from the Messiah to him. Honestly, I was hoping to write a script about Nauli (The Messiah’s name), but after the screening, I realized that Antimoz has an enthralling quality, and it would be detrimental not to explore more about him. I cannot give you the exact details, but certainly, Antimoz’s story starts from the eclipse when the audience can no longer distinguish the motion on screen. In the end, this gullible, flamboyant, infantile man dodges his vulnerability and establishes a new cult from the grain of indecency. Maybe he becomes the new Messiah, a compulsively needed shepherd, but the wrath towards the throng on his face is detectable, or perhaps by strict abstinence, he will gradually gain God’s glorification and become a holy man whose corpse will be preserved untarnished. One can never know.