Arriving during the rise of John Woo’s career, “Bullet in the Head” doubles down on his trademark style but was also an honest reflection of the political turmoil at the center of Hong Kong in the 1990s. Though Woo is known for pioneering action cinema under the sub-genre of Heroic Bloodshed, the essence of his male protagonists is defined by their time and place. In “Bullet in the Head,” Woo and his co-writers Patrick Leung and Janet Chun set the film in 1967 during the height of the Vietnam War. They metaphorically dissect the tensions of the time with Hong Kong during the 90s and the impending handover to mainland China.

This manner of philosophical depth and struggle is not what John Woo is known for. Bullet in the Head’s period setting tackles the politically charged milieu head-on, unlike his other rooted action films. Ironically, the writing uses the environment as a backdrop threaded with classic action sequences that define John Woo’s auteurist sensibilities. Tying these together in a way that doesn’t devalue the socio-political landscape of its time is no easy task. The writers manage to make a wholly satisfying film through the character writing, creating a narrative about three friends trying to get rich quickly during these tumultuous times.

These protagonists and their characteristics, as well as the film’s themes, are established right from the beginning. It’s an economical piece of writing and editing, which is also done by John Woo. A montage tracked to an ironically soft and peppy number introduces Ben (Tony Leung), Frank (Jacky Cheung), and Paul (Waise Lee). The trio are childhood friends and members of a street gang, fighting for territory with other hooligans led by Ringo. Ben is a leader with a strong sense of responsibility and practicality. He’s also quite the Romeo and is in a relationship with Jane (Fennie Yuen). Frank is the black sheep of his family, the innocent, funny man of the group who follows where the others lead and is fiercely loyal. Paul is the wise one, determined to make more out of his life so as to not end up like his poor father.

All three are the disenchanted youth of a troubled world, with Hong Kong around them engulfed in riots between the government and communist rebels. These problems never seem to be the center of their troubles but affect them subtly. The visual language enhances the encroaching threat of the social milieu onto the characters. For example, in the opening montage, Frank is flirting, unaware that the Police have taken off with his father, who is suspected in the tensions. The police are a constant presence that characters don’t notice, whether it’s Paul preparing to make deals to become a smuggler or Ben and Jane romancing outside cinema halls. Even when Ben proposes to Jane in the grassy hills of the town, the ominous shadow of a rapidly urbanizing Hong Kong is showcased in the backdrops.

The editing of John Woo equally plays its part in tracking this change in the setting and its effect on the character arcs. Fade-outs mark the different chapters of the film, with time being a malleable element reflected in the excessive use of dissolves. As the film’s editor, John Woo also uses freeze frames to punctuate significant shifts in the relationships between the characters.

Showcasing the key friendship early on, we witness the trio go freely cycling in their neighborhood streets. This moment is made all the lighter by the consistent dissolves and Woo’s patented use of slow motion. It contrasts because this isn’t an action scene but the punctuation of that core theme of friends as family and the bonds that tie men, which runs throughout his oeuvre. It’s also a neat piece of foreshadowing when Paul and Ben battle to see who’ll win the race while Frank just looks to ride. He nearly falls into the water at the pier while riding fast, saved barely by Ben as Paul watches. These little moments do well in understanding the individual dynamic between the three men.

When Ben gets married to Jane, it is Frank who risks his life getting a loan and fighting off Ringo to pay for their wedding. The freeze frame Woo utilizes at the wedding of the three friends encapsulates their united dreams and bonds. It also marks the biggest act shift in the narrative. The injury Frank suffers at the hand of Ringo spurs Ben into action, causing him to murder their rival. Their reliance on Paul mirrors the two’s closeness to get them out of trouble, as always. This sends the three men running to Vietnam with the promise of becoming wealthy as contraband smugglers.

Where the characters were once ignorant of the social strife of their era, they are now thrust into the political hellfire of the world. It’s fascinating to see John Woo use distinct styles in filming the actual historical sequences of Vietnam versus his general depiction of cinematic action. John Woo also uses his signature action choreography for exciting effects. Before Ben escapes to Vietnam, he meets Jane in the middle of Communist riots in Hong Kong. The scene is meant to be tragic and romantic; the cutting and shot-taking instead treat it like a classic John Woo action film. Slow motion depicts the rising tension and impending break in their relationship. It is intercut with a bomb squad failing to prevent an explosion caused by a time bomb left by the rebels. The visual subtext is rich.

In comparison, when Woo sends the protagonists packing to Vietnam, the political riots in Saigon are captured through guerrilla filmmaking. The documentary filmmaking style in this chapter highlights how the real world will soon encroach on the characters’ personal space. A majority of this chapter still operates like a traditional John Woo action film, the balance of which is masterfully done by the filmmaker. The three men meet Luke (Simon Yam), a hitman who provides them with weaponry to take out the gangster lording over a nightclub in the city. Luke has his own agenda, wishing to escape with his lover Sally (Yolinda Yam), the tortured nightclub singer kept as an enslaved person by the gangster.

While Ben grows close to her and Frank is enamored by her singing, they choose to help Luke and Sally run back to Hong Kong. Paul realizes there’s a case of gold leaf the gangster receives from the Vietnamese Army and CIA for betraying the Vietcong rebels. Paul joins their mission, his ambition driven by money as opposed to theirs to save Sally.

Woo stages the action within the nightclub, and it’s frantic, full of his traditional Gun-fu display as well as explosions. The electric nature of the sequence is enhanced by the cutting and sound, with tensions rising as Paul struggles with his friends over their conflicting morals. It foreshadows the film’s second half as the heroes turn the tables on the gangster but also get caught.

Their race against the criminals chasing them is fraught with trouble as the land outside Saigon is riddled with the Vietcong and military in conflict. The trio of protagonists is pushed farther into the brink of the political landscape, buoyed by Paul’s ruthless desire to cling to their wealth, while the other three men struggle and fail to keep Sally alive. Eventually, as a saddened Luke makes his escape, the protagonists are captured by the Vietcong.

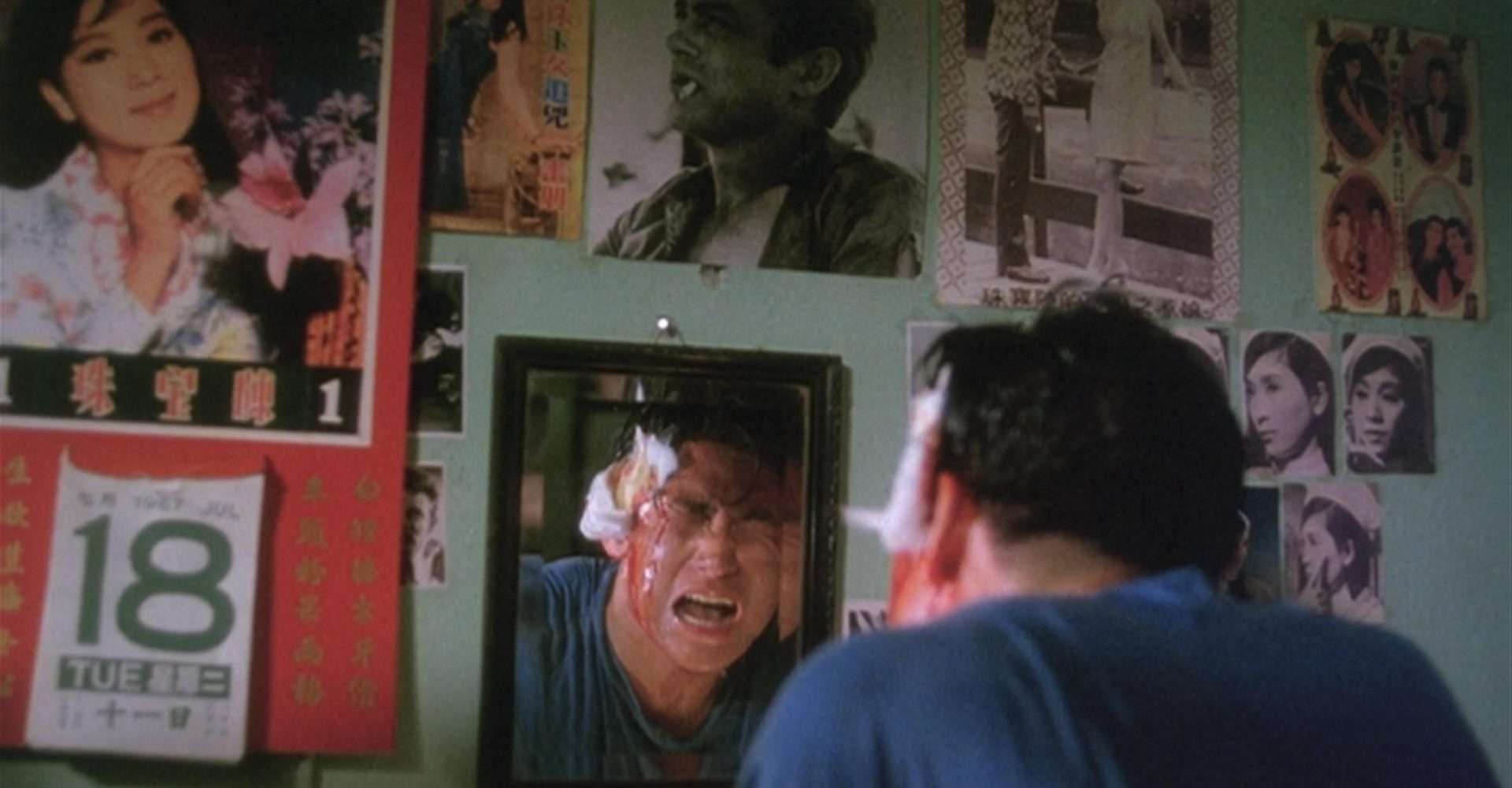

This is where the narrative falls into a tragic tone, bringing out the full force of the horrific time period on the characters. It alters the dynamic of the treatment without ever feeling disconnected from their arcs or the genre. For a moment, the viewer forgets this is an action film as the Vietcong tortures the three men. Paul is still desperate for the gold and gives in easily. Their bonds are tested as Ben is thrust as leader to force Frank to kill the American soldiers in the POW camp for the amusement of their captors.

The breakdown of Frank and Ben’s psyche as they go through this ordeal turns their arcs. It lets both Jackie Cheung and Tony Leung delve further into their performances. Oddly, at this juncture, “Bullet in the Head” reverts back to its roots as an action film. Luke arrives to the rescue with the full force of the CIA-backed American soldiers. It’s the kind of bombastic action set-piece one would expect from the climax of a John Woo film, yet there are still lots of narrative threads to unravel.

The bubbling tensions between the protagonists aren’t lost, as Paul’s ruthless ambition causes him to ultimately sacrifice his friends for the gold. In a bid to hide from the Vietcong during the skirmish, Paul shoots an injured Frank in the head to shut him up. This is where the film earns its title: the bullet lodged deep in a wounded Frank’s skull. Though they are ultimately saved, Ben by village Monks and Frank by the CIA, the dynamic of the three men has been ruptured. When Ben returns to the real world, he is confronted by the tragedy of Frank. Frank has become a mentally deranged killer for the gangsters in Saigon, all so he can use drugs to quell the pain from the bullet in his head. As the lead, Ben goes through the tragic arc of having to free his friend from his troubling situation.

Tony Leung and Jackie Cheung play off each other magically, with the melodrama of Woo’s macho classics breaking through. Cheung is exceptional as the once funny, innocent young man losing his sense of self. In turn, Leung carries the burden of his arc with an internalized performance that explodes in the climax against Paul. Waise Lee isn’t left behind either, known for portraying villains; the last chapter sees him as a rich man in Hong Kong. When Ben returns home, he is confronted by his wife, now bearing their young son. Determined to do right by his family and not lose them again, but also burning with vengeance, he takes action.

This last chapter could have suffered with the lack of time, shifting from the broken dynamic to an all-out war between Ben and Paul. Yet, John Woo finds simple ways to present the dramatic stakes of the situation while giving us a satisfying action-packed climax in one long sequence. A car chase is the perfect way to round out an action film and that is what exactly happens in the final fight between the two former friends. John Woo uses the slow motion of the two men bashing their cars toward the pier. John Woo envelopes this in a flashback with the earlier scene of the three friends cycling in the same place.

The impeccable production design that has captured the subtle changes in Hong Kong and Vietnam throughout works magic as it displays how much has changed in the setting since their youthful days. Staging the climactic action scene on the pier also reflects the altered dynamic between the two and the evolution of their arcs. Their last fight is fuelled by melodrama as much as it is blood, guns, and explosions. It’s the incredible cocktail John Woo’s action cinema concocts that has made him such an influential pioneer of the sub-genre. Like with Frank, Ben is forced to put down a wild and reckless Paul (a scenery-chewing turn by Waise Lee) in order to free the three men from the troubles of their world.

As operatic as he is in crafting his set pieces, John Woo proves he is equally adept at making a Shakespearean tragedy from characters of great depth. “Bullet in the Head” is a reminder that John Woo is considered a master because of his expertise and supreme style. At the same time, some of his great works, like this one, also possess great substance.

![The Suicide Squad [2021] Review – An Optimistic orchestra of Exploding organs](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/The-Suicide-Squad-768x432.jpeg)