Simone Scafidi, the director of “Dario Argento Panico,” is like a little child who has grown up with the films of Mario Bava, Lucio Fulci, Dario Argento, and all other horror and Giallo masters. As a result, Scafidi, especially in “Dario Argento Panico,” feels like a researcher trying to dissect one of these horror masters into the fundamental aspects of themselves and then explore them piece by piece. There is also the minor topic of making a framing device around the documentary, for which Argento’s propensity to retire to a remote hotel to work on his screenplay is chosen by Scafidi.

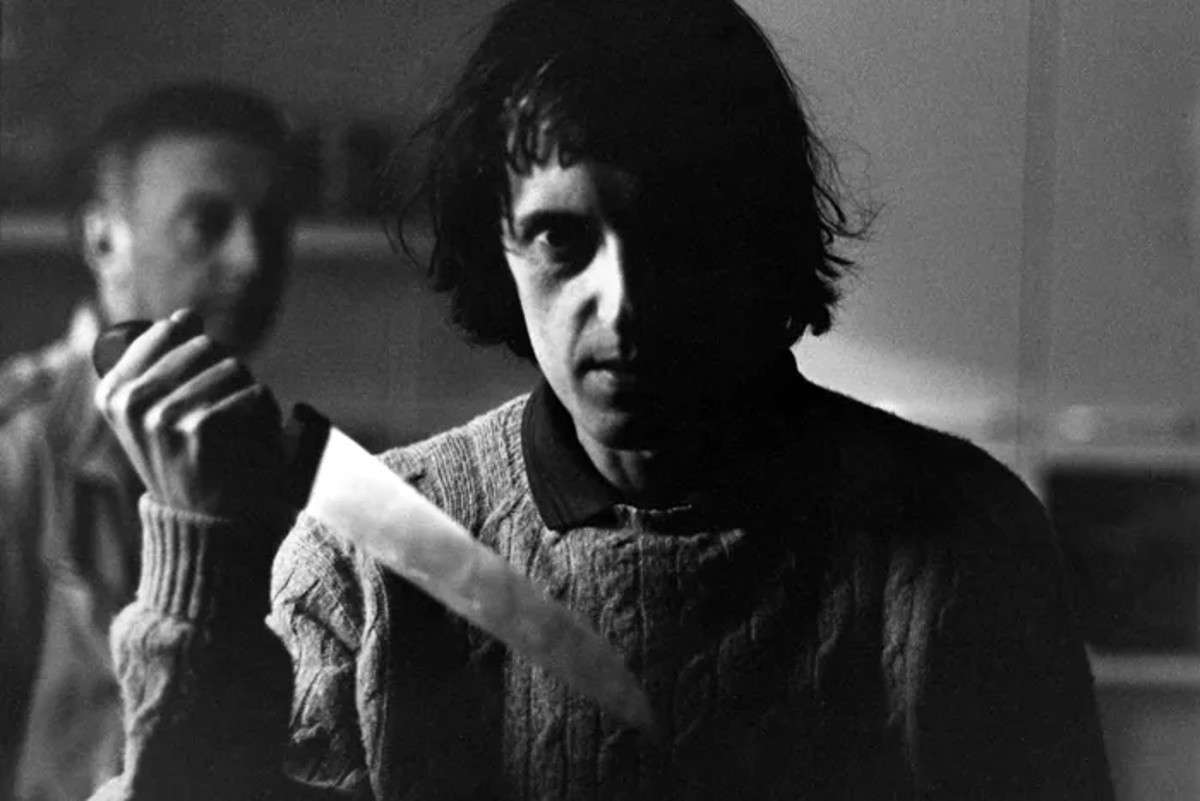

As the movie opens, we see Argento traveling with the documentary crew, interspersed with footage from “Suspiria” (1977), when Suzy takes the taxi and travels to the dance school through the torrential downpour in Freiburg, Germany. There are also moments where Argento is pacing through the hotel and wondering in silence, which is framed like one of his giallos through the signature camera angles. But Scafidi doesn’t take this thread of the “Screenplay” towards any substantial resolution. The “MacGuffin,” if one can call the conceit of this retreat by Argento, is that he is writing a new screenplay for his next movie, but there is no further exploration on that front by Scafidi.

A similar form of introduction to a fascinating plot thread is the presence of women in Argento’s life. The documentary is divided into four chapters, each covering a part of Argento’s life, weaving in important moments of his filmography. One of those fascinating insights comes from both Argento and his daughter, Asia. Argento describes how much he had been influenced by his mother (photographer Elda Luxardo) and her skills in photography and framing women sensuously and yet with strength.

It is in these moments that he also points out how that helped him and Bernardo Bertolucci craft a strong female character as the protagonist in Sergio Leone’s “Once Upon a Time in the West,” but it also influenced Argento’s propensity to cast female characters as the central protagonists or the most interesting characters in his films. A deeper insight comes from Asia, whereby she suggests that Elda must have given up her photography and even repressed her artistic side to take care of her family. Both Argento and his sister had learned through studying her work.

It’s weird how “Dario Argento Panico” never delves deep into the intricacy and filmmaking style of the “Italian Hitchcock,” especially in his staging and his eye for baroque stage pieces in Argento’s best-known works (“Suspiria,” “Deep Red,” “Inferno”). Scafidi leaves those insightful comments to his contemporaries, especially Michelle Soavi and Lamberto Bava, as well as to the auteurs inspired by his horror work, like Guillermo Del Toro, Nicolas Winding Refn, and Gaspar Noe.

From a visual standpoint, whereby the talking heads cut back and forth with archival footage of Argento being interviewed in the 80s, the documentary comes off as a drab and bland overview rather than an exhaustive or uniquely insightful one. And while Del Toro as an interviewee works very well in encapsulating the difference between Argento and his mentors or peers within the Giallo genre—how the environment itself becomes the enemy—such couldn’t be said for the perspectives of Refn or Noe, beyond how much they have obsessed with Argento or how much they have been inspired by him.

In the case of Noe, there is also blatant marketing of his film “Vortex,” in which Argento acted as the older patriarch to shine a light on Argento’s comedic skills. But it is difficult for anyone to care about these perspectives, much less a person completely unfamiliar with Argento’s oeuvre. As someone who is attuned to Argento, almost pushing his aesthetics and visuals towards abstraction and just relishing in the sheer vivacity, Noe’s and Refn’s perspectives feel, at worst, entirely unnecessary.

What truly makes this documentary interesting, though, is how it chooses to delve into Argento’s later-era works. It begins by interviewing Cristina Marsillach, the protagonist of Argento’s 1987 Giallo Opera, where Scafidi slowly, without asking too many leading questions, allows Marsillach to open up about her complicated, contemptuous relationship with Argento during that era.

The explanation furnished by director Michelle Soavi and Asia Argento on why the modernist works of Argento, mostly starring Asia, aren’t as hallowed. Shifting the blame to the removal of standards and practices of Italian television and making Argento’s films revealed as more exploitative than artistic as a consequence is fascinating. It is further emphasized by Asia’s own recollection of her time on her father’s sets, and while both she and Noe eulogize about the open relationship between Asia and her father, a muse, and her director, the discomfort in Asia’s face is readily apparent and very telling.

As a documentary on one of the great horror auteurs, Argento deserves a more exhaustive and deep dive into his filmmaking. Its threads, which Scafidi chooses to dive into, are fascinating to explore. It is both fascinating and baffling to see what hasn’t been explored and what has been inferred but not directly stated. A flawed man who isn’t completely let off the hook because of his prowess in the arts, “Dario Argento Panico” is an interesting overview into the work of one of the defining genre artists, but it does expect you to have seen most of his filmography.

![Chhorii [2021] Review: Another Feminist-Horror Film, Lost in its Own Sugarcane Fields of Jump Scares & Bad Acting](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Chhorii-2021-768x403.jpeg)

![Nine Days [2020] Review – A tender and metaphysical tale about the human condition](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Nine-Days.jpg)