One could say that Astruc’s professions as a journalist, novelist, and film critic influenced the creation of the Auteur theory. The notion of caméra-stylo, or ‘camera-pen,’ developed as a movement after the nouvelle vague or New Wave in French Cinema, reconstructed the director’s role in producing a film. Earlier, films were understood to be a collaborative enterprise between people of different expertise, where neither had total control over the end product. This was especially visible in Marxist films; private ownership was shunned in most (or every) aspect of life in accordance with the communist ideology. Lenin had often said, “that of all the arts, the most important for us is the cinema.”

First published in Kino-nedelya (No.4, 1925), Lenin’s directive for Soviet film-making issued The People’s Commissariat for Education to not only supervise the content of the films but also to integrate them into systematized business. The Soviet leaders were aware of the country’s widespread illiteracy and sensed cinema as the ideal tool for imparting propaganda and education. Two categories were fixed: films for the purpose of entertainment and advertisement (without obscenity) and films with special propaganda shown under the heading, “From the life of peoples of all countries.”

The limitations imposed on the director were multidimensional; the political message to be imparted must be evident, the films should not lead to critical thinking or questioning, and since films were considered a novelty in the villages, the crowds were more susceptible to the message; hence intellectual films which earlier only catered to the bourgeoisie should be simplified for the village audience. However, in contrast, the auteur theory emphasizes films are a reflection of the director’s own artistic vision and thematic/visual representations that get associated with that specific director, creating his unique identity. This would lead to the emergence of a specific style of direction but, at the same time, would impart freedom of exploration and expression to the director, restoring cinema as an art form rather than a mere political medium.

After the fall of the Tsarist regime, the democratic Bolshevik government faced a young Soviet Union that was primarily made up of different nations and ethnicities. To employ the central idea of Communism, which was to abolish private property and create a classless, stateless society, the masses needed to be educated in those political principles. However, that was improbable due to the widespread rate of illiteracy. Thus, as a medium, film was considered ideal for revolutionizing the masses and exhibiting technological innovation and mechanical proficiency as an industrial expertise.

The new generation of communist artists, like Dziga Vertov, Sergei Eisenstein, Pudovkin, etc., took it upon themselves to transform films from a medium of entertainment into a powerful source of communication that impacted all masses alike. Despite the young directors’ embracement of the Marxist theory and incorporation of those ideas into filmmaking, only Eisenstein applied it to all aspects of his film direction.

Starting from the selection of his camera angles to his theory of ‘montage of attractions,’ which juxtaposed images for the generation of specific emotive responses; his focus on form and movement within frames and later, even in the selection of sound and music, elevated Eisenstein from a true-blue Soviet director to a revolutionary auteur of methods in film-direction. “Dnevnik Glumova” or “Glumov’s Diary” was Eisenstein’s transitionary step from theatre stage direction to films. An adaptation of 19th-century Russian playwright Ostrovsky’s “The Wise Man” (“Na vsyakogo mudretsa dovolno prostoty”), Eisenstein inserted the anti-hero Glumov to convey the same message albeit through clowning and acrobatics.

As a trained architect, Eisenstein developed a whole new science of film editing (and making) based on Marxist dialectics. Having worked under Russian director Dziga Vertov, a pioneer in the cinéma vérité style of documentary movie-making, Eisenstein had already been exposed to expressive directorial techniques and assemblage of film clips without regard to formal continuity of time and logic, which leads to a ‘poetic’ effect in films. “Strike” (1925), his first full-length feature film, juxtaposes the chronicling of the strike carried out by workers just before the 1905 Bolshevik Revolution with dramatization for affect. The film is divided into six parts, progressing linearly, lulling the audience into viewing it as a story.

To amplify that effect, the actors dramatize their expressions (which is similar to the theater technique of ‘mime’), and Eisenstein adds practices like gossiping to make it more relatable. Two scenes stand out as highlights of the film: the first being the suicide of the worker, which unites all the other workers of the factory against the hierarchical officers. The second is the montage of the slaughterhouse with the chaotic dispersion of the workers when attacked by the Tsarist police, drawing parallels between both. This brings one to understand an important shortcoming of montaging: the difference in affect on the audience. The bourgeoisie would react differently to this than the factory workers who are desensitized to blood (seen by them as a factory by-product).

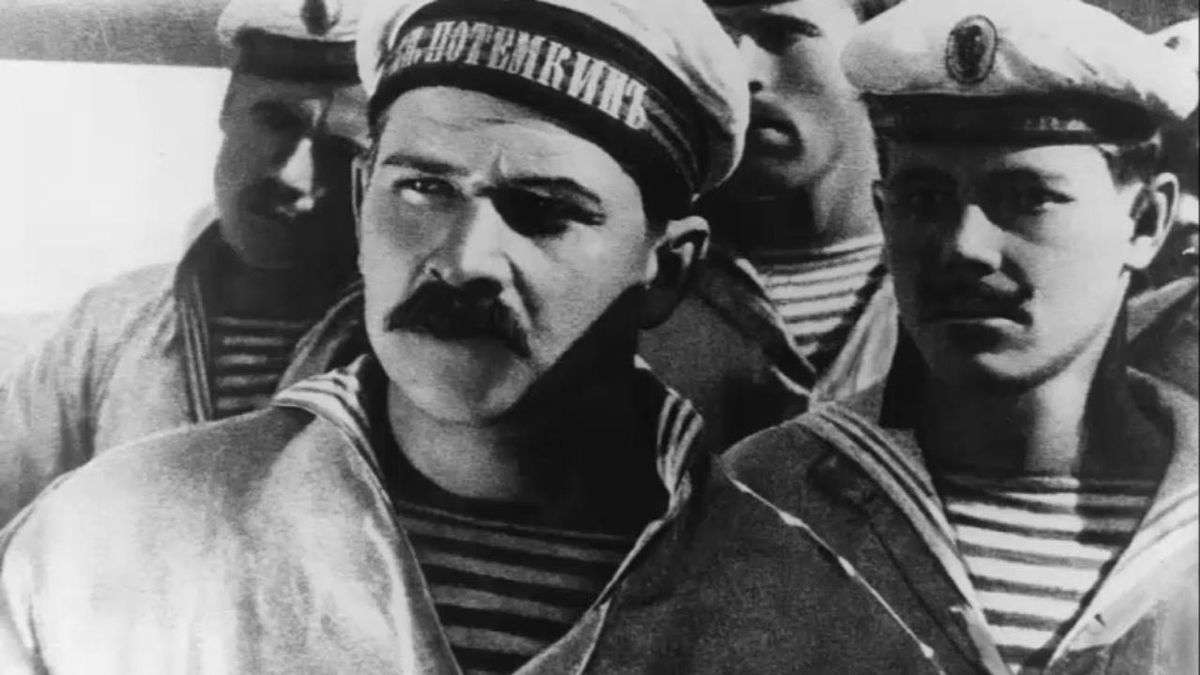

However, Eisenstein’s most iconic film is “Battleship Potemkin” (1925), which stirred the audience into making their own revolution. Eisenstein’s remarkable selection of imagery of maggot-ridden meat served to the sailors, cruelties by the officers, and the methodical shootdown of innocent citizens on the stairs of Odessa by the Tsar’s Cossacks stirred the exact sentiments he aimed for. “When “Potemkin” is discussed, two of its features are commonly noted: the organic unity of its composition and the pathos of the film.”

Eisenstein employed Engels’ focus on unity (in Dialectics of Nature) through the composition in “Potemkin,” which was both proportionate and structured, to psychologically manipulate the audience’s emotions and retain its artistic nature. However, after being criticized for his formalistic ways of film direction, Eisenstein made his comeback with the “Ivan Trilogy.” However, Que viva Mexico! would have been his boldest film due to its deviance from his formalistic cinema, further establishing him as a cinematic genius. As an auteur, Eisenstein is especially renowned for carving his niche in a totalizing environment meant to contain a director and restrict progress that might lead to questioning.