10 Great Films That Helped Cinema Grow As An Art Form: Since the inception of the medium, films have garnered new meanings for their ever-expansive exploration over the decades. From the Soviet Montage that introduced innovative ideas and efficiency in the editing process, German expressionism working on the atmospheric disposition, the French New Wave conceptualizing subversive methods breaking storytelling and narrative boundaries.

Thus, the medium has been explored and experimented with by various filmmakers and film movements, helping cinema grow- mechanically and philosophically. Cinema and its viewers have evolved simultaneously, with filmmakers providing challenging experiences and its admirers religiously observing and understanding the art and craft behind it, its various associations with society, culture, the human condition, and its subsequent effect on the viewers. Often touted to be an amalgamation of other forms of art- music, photography, and literature; the film has had a challenging time being accepted as a singular art of expression and communication.

Related to Cinema as an Art Form: Why Do We Love Movies?

This list consists of films that stress upon the notion that cinema is an exclusive medium, that film is a language of its own, able to express itself as a distinctive organization. It consists of films from different eras, from all over the world, subscribing to its nature of timelessness and individuality. The list is not conclusive or exhaustive but exemplary of film withholding its unique identity as a form of art and medium of expression. Here are 10 Great Films that helped grow Cinema as an Art Form.

Vampyr (1932) | Director: Carl Theodor Dreyer

Vampyr, Carl Theodor Dreyer’s sole film of the decade, following his most acclaimed project The Passion of Joan of Arc in 1928, is a subversive revolutionary horror drama. Allan Gray, the protagonist, rents a room in a small lodging in a village named Courtempierre, he experiences strange encounters enveloped in supernatural and spiritual acts structured in a disjointed narrative. With his previous endeavor, Dreyer focused on photographing faces and explicit emotions to help aggravate the themes. Vampyr although fundamentally aims at achieving the same transcendental experience, functions in a completely different world. The narrative is punctured and wanders onto unknown territories of experimentation with sounds and images. Dreyer uses the plot, events, and characters as tools to communicate a very personalized, internal experience of Allan Gray and his fascination towards the metaphysical stature of vampires.

Related to Cinema as an Art Form: 10 Classic Black and White Horror Films That Still Hold Up

Through editing techniques of superimposing images and wrapping them with an enigmatic score that enforces and guides an otherwise fractured story- Allan Gray’s experiences dwindle and aggravate in a lingering fashion. Dreyer’s cinematography utilizes shadows and abrasive lighting to enhance the sinister, supernatural architecture of the inn. The mannerisms and acts of his characters teamed up with the trademark conflicted Christian spirituality of Dreyer are juxtaposed with the frontal themes of the film. Vampyr is not just unique and revolutionary with its creative filmmaking techniques but how it enforces those techniques to push and elevate the narrative, its characters, and themes which circumvent the supposed climax in a very consciously loose knitted ending open to inexhaustible interpretations. Vampyr books its slot in one of those rare films from the developmental stages of cinema that stand the test of time, as Paul Schrader would suggest, largely due to its transcendental nature.

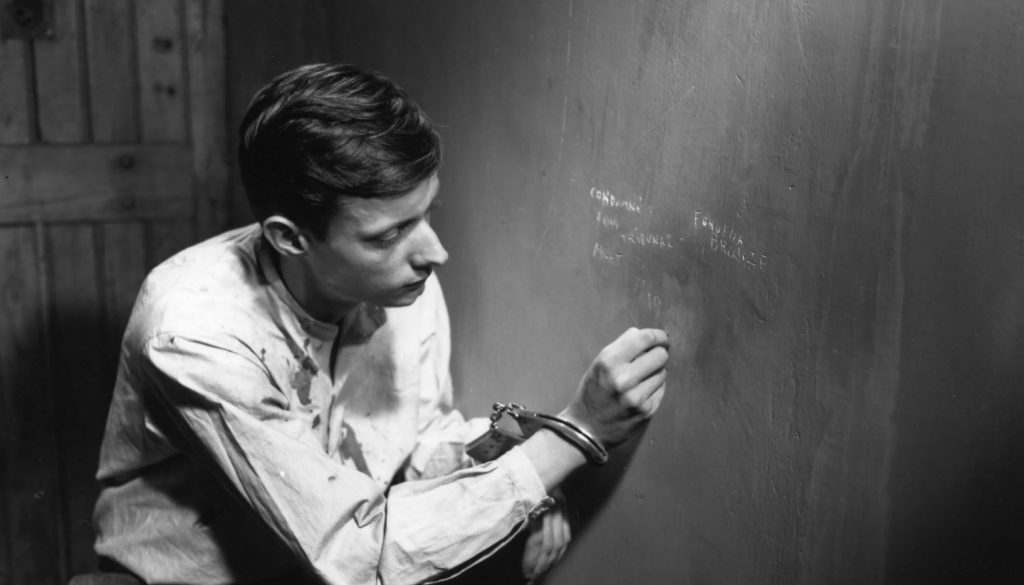

A Man Escaped (1956) | Director: Robert Bresson

French auteur Robert Bresson’s fourth feature A Man Escaped, is a semi-autobiographical film about a French Resistance fighter’s escape from prison during World War 2. Robert Bresson negates an important aspect of conventional cinema concerning the engagement of the viewer when he titles the film, A Man Escaped. He has an antithetical language of filmmaking, focusing on showcasing thematics through the internalization of characters and their exhibited actions. A Man Escaped is driven by a desolate narrative that builds upon the protagonist Fontaine’s existential dread through the captive narrative. Fontaine narrates his experience in what appears to be seemingly mundane but spectacularly detailed, emphasizing the process of his escape through communication and tools, furnishing his recitation with simultaneous accounts of his subconscious thoughts and feelings with utmost sincerity. Bresson, in his audio-visual style, propagates and exercises his images constantly attempting to evoke the film’s transcendental nature, exerting upon the viewer- the experience and insight through the prison with glaring universality. His editing process and selection of shots- enumeration of Fontaine’s activities in demanding order and care rewards a unique, responsibly precipitated experience.

Related to Cinema as an Art Form: 15 Best Films of Jean-Luc Godard

A Man Escaped evokes the viewer not only concerning the film but the filmmaker as well. Robert Bresson’s filmmaking philosophy of concealment, photographing the ordinary, the truth in a certain singularity translates into a form of filmmaking, absolutely recognizable of his craftsmanship. With the explicit film title, A Man Escaped, Bresson, dries the climax from the very beginning of the film; which directs the viewer’s experience and observation into Bresson’s radical and timeless philosophy of filmmaking. Mozart’s music that is sparse yet precisely used is meditatively powerful, reaching its peak, both structurally and sentimentally towards the end, when the young accompany of Fontaine after escaping says, “If only my mother could see me”, before evaporating into the dark. A Man Escaped is one of Robert Bresson’s most notable works, in his short, consistent, and timeless filmography. Robert Bresson, one of cinema’s powerhouses and a 20th-century revolutionist manages to provide one of the briefest, most minimalist, and life-altering experiences with A Man Escaped, exploring the expressionistic medium of cinema.

Woman in the Dunes (1964) | Director: Hiroshi Teshigahara

Woman in the Dunes is Japanese filmmaker Hiroshi Teshigahara’s sophomore outing in 1964. An entomologist’s exploration in the desert to discover an insect for further research and inspection for recognition purposes. He’s misled by a group of locals who dupe him into living in a feeble settlement in a confined pit in the desert, along with a woman. The film deals with various themes and subjects expanding upon its scope in transcendental terms. The mysterious score from the very first frame obtrudes with the images of seeping dunes featuring minuscule locomotive creatures that glide in and out of the vast landscape, all of it captured through volatile cinematography. Teshigahara’s vision is instantaneously communicated within the first few minutes of the film’s atmospheric essence and stark lighting. Woman in the Dunes carries itself gradually as the narrative progresses with the Entomologist and the woman in the house. There is an unbridled philosophical clash between the two owing to the man’s urban outlook and materialistic world view and constant quest for change; the woman’s restrained experience in the rural scape and vivaciously dutiful character.

Related to Cinema as an Art Form: What Happens When A Woman Ascends The Stairs

Characterized by constant engagement of ideology concerning what both of them desire in life, their regrets, quarrels over morality under layers of the patriarchic notion, and the entomologist’s constant attempts to escape the unknown territory. Teshigahara augments the plot to a metaphysical level, moments of sexual tension and collision of their bodies, the colossal sandscape portrayed as blistering and gigantic terrains gushing waterfalls one moment and as serene and lush streams meandering harmlessly, through free form cinematography and dreamy editing. The film seamlessly inputs social commentary through a ritualistic sequence wherein the villagers aiming their razor-sharp fire sticks, lighting the pit, demanding the couple to perform sex. It organically infuses themes of consumerism and the orient with its strong visual communication withholding the mystery intact. Woman in the Dunes is an inexhaustible experience that demands multiple viewings, it offers a powerful atmosphere amidst a snarling narrative and transcends as a revolutionary piece of film experience through its visual style and form.

The Color of Pomegranates (1969) | Director: Sergei Parajanov

This film is a biographical piece on the life of an Armenian poet, Sayat Nova. Russian experimental filmmaker Sergei Parajanov, in this film, expands upon the poetic and political cross-section of livelihood in an era orchestrating culture, stigmatized themes, and extraordinary use of symbols to elevate the narrative. Set designer Mikael Arakelyan vivaciously stages every inch of space provided to him as a painting. Narrated in an endless free form structure, the film, as recuperating the times of the past, progresses in the same dreamy format. Parajanov’s vocal artistic vision is communicated through striking, belligerent frames and Tigran Mansuryan’s score accentuating the themes and claustrophobic yet enthralling atmosphere. The Color of Pomegranates do not take any breaks, it consistently builds upon itself from all sides- score, sets, themes and maintains the dazzling quest of Sayat Nova’s life and poems. He explores subjects and events in his life in a chapter-wise format- Childhood, Youth, Prince’s Court, The Monastery, The Dream, Old Age, The Angel of Death, and Death.

Parajanov claimed to have wanted to explore the inner dynamic nature of Armenian miniatures he was inspired from. Purposeful and sentient use of color and texture in a wholly mystical, religious piece of work that comfortably reinvents the medium of cinema as a form of expression. Images that go from a child laying on the roof surrounded by serially arranged books to an unwavering, blood-curdling display of chopped sheep heads. Sergei Parajanov internalizes the cultural conditioning to unseen playing fields through the run time, sprinkling a variety of colorful and dense emotions, shot completely in real locations, from monasteries, medieval churches, and ancient settlements. The experience is describable through nothing but its formative cinematic language.

Pastoral: To Die in the Country (1974)| Director: Shuji Terayama

One of Japanese cinema’s gifts to the world- Shūji Terayama, is an avant-garde who creates a world in his films through striking visuals and revolting yet mystical soundscapes. Pastoral: To Die in the Country is a film about a boy’s coming-of-age tale, squashed into memories and dreams, themes of adolescence and desires rooted in rural Japanese culture and mythology gradually being engulfed in political volumes along with an impossible-to-forget meta cinematic feature in it. Terayama paints his images with energetic colors to support the surrealistic imagery of the film, lush orange skies, blue lands along the mountains, and the countryside. The ethereal soundscape quarreling with the sometimes high-spirited sometimes introspective music. Sequences throughout the film concerning sexual identity and fantasy explorations are smeared in multicolored pallets. The supposed protagonist’s day-to-day exchanges with his grandmother, fascination with the neighborhood woman he’s attracted to, are juxtaposed with the social customs of the locale he lives in.

The film builds this atmosphere through coruscating compositions and camera work, numerous top shots hint towards the distant and alien relationship between the boy and his family, landscape photographs at disposal symbolizing many themes of vehemence, high spirit, and exuberance. The pacing of the film holds the dreamy, rhythmic structure throughout its runtime. Terayama’s trademark shifts in the color pallet are extremely fascinating. The meta cinematic turn in the film brings up a whole new layer and perspective, closer to the present day without distancing itself from its previous commute. The explorative personality of Shuji Terayama is piece by piece realized towards the end, the last few culminating minutes which could be regarded as an ode to cinema, at its most experimental and equivocally enigmatic to have come to fruition and fulfillment. The climax brings about two polar fork’s of universality and personality onto a single plate in one of the greatest “welcomes” or “goodbyes” to the cinema.

The Passenger (1975) | Director: Michelangelo Antonioni

Michelangelo Antonioni’s third and final collaboration with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer is a meandering maundering crime noir, The Passenger. In supposedly one of the finest years in cinema, with releases like The Travelling Players, Mirror, Nashville, India Song, Jeanne Dielman, Barry Lyndon, and Dersou Uzala. The Passenger stands in its unique, tall stature as an unorthodox tale of David Locke, a journalist covering a piece in North Africa. He assumes the identity of a dead businessman who turns out to be an arms dealer, facing a series of conundrums as the story progresses. Like the rest of his filmography, Antonioni religiously sticks to his style of wandering, drifting cinema; deserted pace and nonchalant movement of the camera. Unlike conventional filmmaking techniques, he flips the funnel upside down and starts pouring his themes and structures that splatter, very consciously in full control of Antonioni. Existentialism and identity are at the forefront of The Passenger. Antonioni mordantly intertwines quests for truth with political nuances as he explores the North African landscape that David Locke scales and the rebels from the region that he interviews.

Related to Cinema as an Art Form: 10 Best Jack Nicholson Film Performances

There is a fascinating segment of exchange between them that circumvent the thematic scope of the film, David asks the rebel, “Isn’t it unusual for someone like you to have spent several years in France and Yugoslavia, has that changed your attitude towards certain tribal customs, don’t they strike you as false now and wrong, perhaps for the tribe?”, he replies, “Mr. Locke, there are perfectly satisfactory answers for all your questions. But I don’t think you understand how little you can learn from them. Your question is much more revealing about yourself than my answer would about me.” To Locke’s, “I meant them quite sincerely”, Antonioni’s camera leans forward stealthily, the Chadian further digresses from the subject but progresses within the scheme of the film saying, “Mr. Locke, we can have a conversation, but only if it’s not just what you think is sincere, but also what I believe, to be honest.” He turns the camera around with David’s face fixated within the frame, resolutely saying, “Now we can have a conversation, you can ask me the same questions as before.”

This particular dialogue exchange, brimming with subtext, not just what the characters suggest but what the scope of filmmaking Antonioni is leaping to achieve. The most significant aspect of the film is how it refrains from leading or guiding the viewer. The characters, the viewer, and the filmmaker start the journey together- discovering and exploring events under serene meditative clouds filled with thought-provoking visuals and themes, pouring uniformly. The film culminates in an iconic near 10 minutes unscathed shot of Michelangelo Antonioni cautiously handling the camera, the same way he handles the film’s intentions and responsibilities, and unassertively bursts upon its viewer with questions, incertitude, and wonderment, in one of the most uniquely crafted masterpieces of cinema.

Close-Up (1990) | Director: Abbas Kiarostami

Abbas Kiarostami read about a trial of a man conning a family into believing he was Mohsen Makhmalbaf, an acclaimed Iranian filmmaker, convincing them that they would play a significant role in his new film. Kiarostami amidst the pre-production of a project immediately shifted focus on making a docu-fiction on this subject. Kiarostami, coming fresh out of one of his best projects, “Where is My Friend’s Home?”, delves even deeper into the perennial nature of reality and the primordial question, what is the meaning of art? A poignantly crafted film, Close-Up constantly shatters the conventional boundaries of reality, it ponders upon the postmodernist theory of Hyperreality wherein there is an underlying conflict between reality and the simulation reality. It imposes upon the viewer to not only contemplate philosophical ideologies but simple unsophisticated humanism that Kiarostami seems to be a master of. Through Close-Up, he challenges the divisive notion of morality, of what is wrong and what isn’t, relatively or absolutely.

Related to Cinema as an Art Form: 10 Best Iranian Films Post Iranian Revolution

Close-Up furthers the dimensions of what art can achieve and imply, with a plaintively arranged score and sincere long takes he brings the film and the people in it to life, handling every aspect of the film, including its implications and depiction with utmost responsibility. Towards the final act, Hossain Sabzian, the accused man is forgiven by the family to who he is grateful, he meets Mohsen Makhmalbaf and goes to meet the family with him along with flowers by his side. The climax oozes the redemptive character of the whole event allowing Hossain to reinvent himself. Close-Up ends with Hossain holding the flowers with humility, looking down with a subtle grin, the frame frozen at the sight while the credits roll inviting the melancholic, compelling score to breathe in one of the most iconic shots and achievements in film history.

Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010) | Director: Apichatpong Weerasethakul

Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives is the sixth full-length outing of Thai visionary Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s universe. A floating, hazy story about Boonmee- a veteran suffering from acute kidney failure, living his last days in the countryside. He experiences a series of events- visit of the ghost of his deceased wife, lost son returning home in an altered form of life; and more before he ceases from existence and admission into death or enters in an overlapping realm of existence. Apichatpong in every audacious drive of his previous outings steers this film into a labyrinthine and invitingly lost world where Boonmee experiences the bridge between the cessation of his present life and admittance to his next. He has mystical exchanges with his close relationships who guide and nurture his ideological conflicts and second thoughts about so perceived death and new life. Apichatpong incorporates the countryside atmosphere to transcend the dialogue amongst the characters, often pressurizing the silence to the point that it gradually condenses into drones and static sound waves accompanied by crickets and swirling trees in the woods.

Related to Cinema as an Art Form: 10 Great Asian Films You Can Watch on Netflix

Apichatpong takes a smooth, near noticeable but powerfully ambitious turn with a sequence of a queen in a chariot in the middle of a tropical forest. Stops by a lake cursing her supposedly unacceptable facial features she regrets and prays to the waters to make repairs for which she offers her possessed ornaments. In a tangential dreamy exchange between them, the narrative ponders upon the materialistic metaphysical nature of life and desires. The filmmaker constantly shifts gears carving new paths and thriving at the crossroads and the traffic of subliminal themes of existentialism, life, death, morality, and memories, without losing its serene atmosphere. Uncle Boonmee ends amusingly, utilizing Penguin Villa’s track Acrophobia towards its finality, in what could be touted as one of the most unforgettably cathartic moments of cinema. Genre subversive cinema is an ambitiously fresh take that has been sparingly yet ambitiously attempted by the heavyweights of cinema throughout history, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, fully belonging to this group also paves unseen bridges and paths of subverting the experiences of life itself. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives is one of those successful attempts along with the rest of his equally audacious films.

Horse Money (2014) | Director: Pedro Costa

A film about the atrocious experiences of the marginalized migrated communities in Lisbon, Pedro Costa’s Horse Money is a visionary piece of filmmaking where the psychological experiences are manifested and depicted physically, through barren lighting, mostly soaking in the darkness that suppresses the light that glows in tight, inflexible spots. Extending into the world of documentary filmmaking and docufiction. Ventura is an old man traumatized from his past experiences is suffering from an illness that serves as a metaphor through his incongruous gesticulation, shivering hands, whispering dialogue, unmoved stature, he represents the effects and outcome of colonialism.

Horse Money also explores the spaces of hyper-realism, but unlike Close-Up that explores it in an ideological drive, Horse Money, encompasses it, ideologically and visually with its aesthetic choices and photographic imagery, carefully crafting and concentrating on the eyes, lips, hands, tears, etc. Ventura meets Vitalina Varela, whose arc seems to be initiated here and fully traversed in Costa’s 2019 film Vitalina Varela. Ventura and Vitalina converse in whispering segments in conjectural shadows, narrating mishaps and their painful experiences, about her missing husband, Ventura’s fervent sickness, and her being. Structured in a fractured format, there is an explicit phantasmagorical element throughout its run time, Ventura drifts off on deserted dark roads with light beams, his conflicted disposition and the film’s hazy, harrowing nature, not just with respect to the content but expressively and cinematically offers a unique, asphyxiating meditation of an experience fully rewarding the patience that it demands. Pedro Costa’s style and philosophy of filmmaking are, although very distant from perceived reality, pulls the viewer closer to physically feeling reality in a densely intangible yet extremely intimate experience.

Burning (2018) | Director: Lee Chang-dong

Lee Chang-Dong’s 6th and arguably most ambitious project to date ponders upon more questions than it seemingly suggests. A tale of primarily 3 characters – Jongsu, Haemi, and Ben. The film begins with Jongsu accidentally bumping into his schoolmate Haemi and start hanging out building a close albeit mysterious relationship with each other. Haemi later goes on a trip to Africa where she meets Ben and they come back home, together. Haemi introduces Ben and Jongsu to each other on their arrival. There are a series of consequent and routine events looming with constant ambiguity. Burning albeit a straightforward act, aggressively comments on the nature of circumstances and conclusions. Amidst its meditative visual scape and exasperating pace, it drifts and contemplates upon situations based on limited information and casual coincidences. Haemi is in the quest for the meaning of life with suicidal tendencies owing to a lack of self-esteem and vulnerabilities from her past, yearning for materialistic gains and recognition. Jongsu is an aspiring writer, a talented one as Ben suggests, who although being extremely wealthy and self-sufficient is envious of Jongsu’s virtuosity.

Related to Cinema as an Art Form: 10 South Korean Thrillers With Socio-Economic Commentary

Lee Chang-dong’s expansion of Haruki Murakami’s short story Barn Burning explores and breaks boundaries of storytelling, completely subverting the genre of mystery films wherein the climax of the film raises more questions rather than providing a resounding resolution. He inculcates Haemi’s precarious and susceptible nature to imply conclusions over explicitly portraying them. While Jongsu seems to be the conventional protagonist, his character is brimming with selfishness, obsession, misogyny, and distasteful envy, Ben, on the other hand, seems to lack antagonizing qualities, an introverted, unenthusiastic personality with the obsession of burning neglected greenhouses, something which Lee Chang-dong treats metaphorically. Burning’s unwavering juggling between dreams and memories escalated and transformed through intermittent guitar swirls and sparse but resolute drum sections. Burning is filled with metaphorical allusions and inconclusive themes that expand the margins of cinematic storytelling.

This list of cinema as an art form may expand in the future, please tell us in the comments what all films could be a part of this list.