Klaus Härö’s “Never Alone” (Ei koskaan yksin, 2024) draws from real events and people during the Nazi years to tell the tale of a man who stood his ground with his ideals. Abraham Stiller (Ville Virtanen) runs a thriving textile business in Helsinki. He and his wife, Vera, are Jews who migrated from Tsarist Russia decades ago. The couple is part of local influential circles, having connections within the police as well. But how far does this immunize them or the Jewish refugee couple they take under their wing and give jobs?

What undoes the film, and whittles away some of its power is the frame narration rendered in trite, uninspired monochrome. A journalist is interviewing the businessman about his past. She questions him about Finland’s deportations of Jews in the 1940s despite it not being occupied by Germany. When she brings up the case of one deportee who survived the post-war trials, Georg Kollman (Rony Herman), he’s thrown into wistful mode and begins a long line of sad reminiscences.

She also becomes the point of reconnection between Stiller and Georg. Even the prosthetics of wrinkled skin on Virtanen look hardly convincing and downright tacky. This monochrome track feels entirely superfluous, as does the use of languorous slow motion in certain sequences, consciously trying to work up a tragic temper. Moments of fateful parting are already invested with emotional heaviness. The stylistic choice makes it duller, unimaginative, and leached of the weight it already would have in the instant.

Stiller is lamenting, regretting his lack of foresight and abundant naivete. But this doleful murmuring holds little depth in its retrospection. Until the eleventh hour, he is insistent the couple stay in Finland even when they express the desire to leave. Stiller pays no attention to the alarm bells signaling doom for the Jews in a country not under German occupation, but instead engaged in military cooperation. The Holocaust and its claws aren’t as distant as Stiller thinks they are. The stakes escalate yet he chooses to repose hope in administrative structures of integrity and honesty.

He had to pay the price of his impassioned idealism. His stubborn belief that Finland wouldn’t bend to the Nazi madness doesn’t pan out the way he hoped it would. There are several lives lost. But at least, his watchfulness and daring intervention curtailed the deportation to some extent. Finnish Jews were spared, while the refugees were shipped away to the concentration camps.

The film swoops on the bureaucratic evasion as well as the brave, unflinching tenacity of a few good men in the forces who refused to play fiddle to fascist currents. It’s on the trust and backing of a handful of upright police officers that Stiller clutches onto his strength and unshakable resolve. Unfortunately, the director of Finland’s State police, Anthoni, concedes no consideration for ‘outsiders,’ being more than eager and welcoming of the Nazi directive even though the country’s Prime Minister remains in the dark. An entire covert operation is mounted under the pretext of a “mere police procedure”, planting fake criminal charges on the refugee Jews.

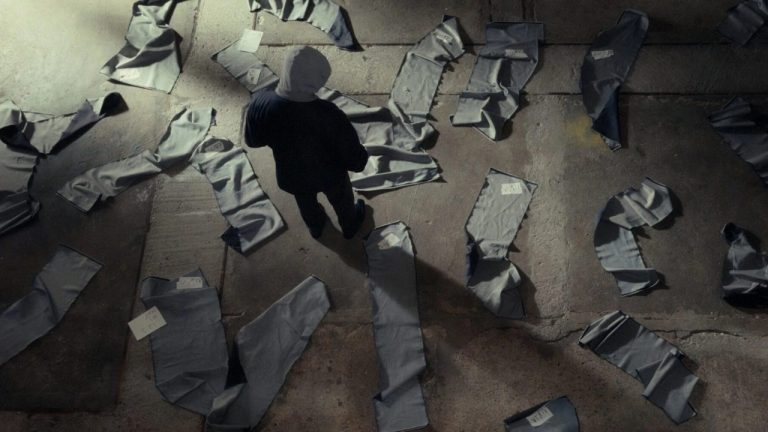

“Never Alone” could have gained momentum if it also incorporated the community Stiller looks over protectively, with almost paternal insistence. The film just bulldozes this by invoking the religious congregation angle to it. Two entire scenes prop up where Stiller insists on reciting the Sabbath with fellow Jews amidst a deeply perilous situation. However, the film relies on the strength of its production value which pulls it through. Härö executes some quietly bone-chilling moments, like when Georg’s wife steps out of the shop onto an empty street. Newspapers dumped on the road rustle eerily. As her glance wavers to a Nazi poster taped on a tree, both she and we are struck by the realization of impending, irrevocable danger.

“Never Alone” is relatively a brief film, as opposed to the overlong, clunky tendencies of period pieces. Yet there are quite a few scenes in it that don’t emotionally or narratively advance the film, like a section in Lapland where the refugees are initially dropped. The film is a mixed bag, one which leaves you wishing for a bit more subdued, lingering tension, a sense of coiled unease. Even the coda, attempting an overtly emotional tie-up, doesn’t evoke much in the viewer.

![Jesus [2019]: ‘Japan Cuts’ Review – The dilemma of belief through the prism of innocence.](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Jesus-Japan-Cuts.jpg)

![Pigs and Battleships [1961] Review – A Probing Portrait of a Marginalized Society](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/P-and-B-768x432.jpg)

![Widows [2018]: ‘MAMI’ Review – Suffers from Incoherent Narrative](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/widows_2018_review_highonfilms-768x384.jpg)