Satyajit Ray’s 1969 visual rendition of Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury’s children’s fantasy “Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne” (GGBB), along with its later extension titled “Hirak Rajar Deshe” (1980), which was originally written by Satyajit Ray himself, has been inhabiting the center of a popular polemic in West Bengal and Bangladesh for ages now, which forays into arguing that these two visual pieces are more than what they seem and must not be understood simply as children’s cinema. Not only has a flux of academic and non-academic articles on these two films kept coming throughout all these years, but the duology has also been, for a long time, significantly central to the space of popular political praxes (mostly in the left milieu).

The current regime in India (led by the National Democratic Alliance) has, on multiple occasions, been analogized with “Hirak Raja” (The King of Hirak) by the West Bengal faction of the opposition, for implementing its draconian acts. During the 2021 Assembly election, when the BJP was attempting to usurp the Bengal throne, a flood of digital posters, carved with images and dialogues from “GGBB” and “Hirak Rajar Deshe,” were disseminated by the opposition parties.

Following Babul Supriyo’s (who was then a junior minister of the central government) visit to Jadavpur University in 2019, which ended in a rampage, as the JU wing of Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) ransacked the campus premises, a huge banner held by the protesters on the next morning read “O mantri moshai, shoro jantri moshai, theme thak” (“Hey minister, mister conspirator, stay put!”), which is a much-celebrated song from the film “GGBB.”

Hence, let alone the question of standing the test of time, the duology remains a postcolonial site of cultural and political reconstruction for a particular community. Both of these films take into account the post-colonial crises, such as landlessness, migration, refuge-seeking, utopian wish-fulfillment, dictatorial power structures, and the possibility of a proletarian uprising (not an armed revolution, though), which places them in the post-colonial critical discourse. Since the spectre of colonialism and imperialism still lingers, with the prefix ‘neo’ attached before them, over the ex-colonies, it goes without saying that the characteristics that shaped the post-colonial trauma are still recurrent in their ‘neo’ forms. Thus, in the subcontinent’s context, the Goopy Bagha saga remains an essential visual text to revitalize the anticolonial agenda during the times of major political repercussions.

The political space that still uses this duology as a resistance weapon somewhat fixates the question of whether we should consider “GGBB” and “Hirak Rajar Deshe” as exclusively children’s cinema or not. The answer is simply ‘NO’, because the taxonomy of the usage of the dyad implies the fact that, rather than children, in the subcontinent, the two films have influenced the grown-ups much more. What I would try to investigate in this article are a few facts (mostly discrepancies) that could problematize the space under discussion if, I believe, scrutinized minutely.

From simpletons to revolutionaries

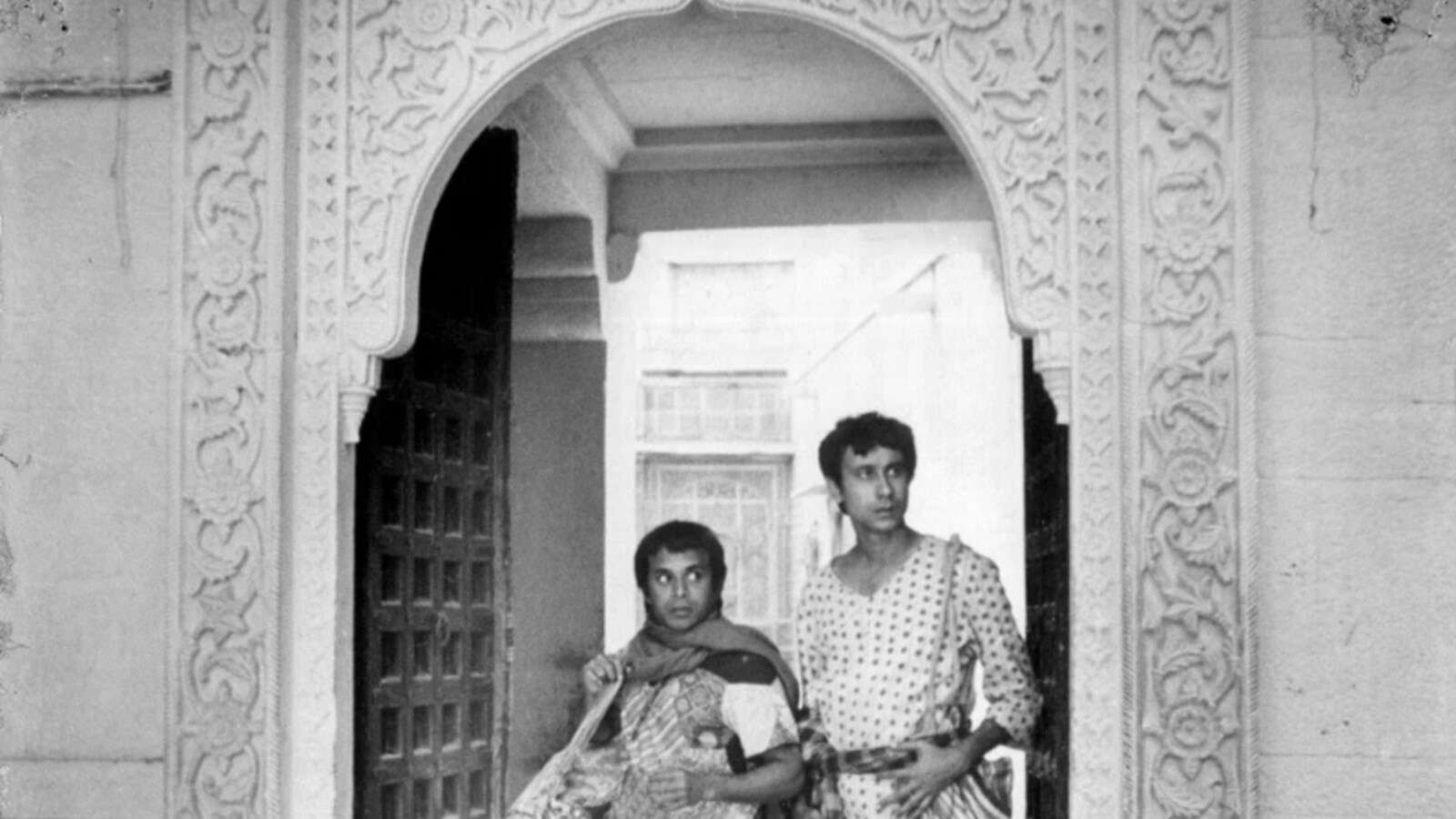

The primary source (Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury’s text) helps us to know that Goopy and Bagha both belonged to lower-caste petit-bourgeois families. Both had a penchant for music, but lacked the necessary skills, which eventually cost them an unexpected expatriation from their native villages. Satyajit Ray, in the visual adaptation of the text, overtly politicized the space by determining Goopy’s spatial position in his village.

Goopy is seen jesting, in the opening scene, with a farmer, whereas in the very next scene, he pays obeisance to the old Brahmins of the village and takes a seat in front of their feet. He also chronicles how Gonsai-khuro (Gonsai’s uncle) – another Brahmin – exploited his physical labour in exchange for a defunct Tambura, which the owner considers ill-omened. The caste discrimination, semi-supine till now, emerges bluntly as the older upper-castes of the village trick Goopy by dictating to him to sing before the king’s palace at daybreak. This enrages the king to such an extent that he expels Goopy from his kingdom.

In the subsequent sequence, Goopy chances upon Bagha, and their rendezvous with ‘Bhooter Raja’ (‘The King of Ghosts’) takes place in a bamboo forest. This sequence – Goopy Bagha’s encounter with the king of ghosts – changes the course of the film and our protagonists’ fates, too. Three boons, that they received from the King of Ghosts, ameliorate their poverty-stricken lives and help them earn a position as the court-singers at the durbar of Shundi’s king. Since then, Goopy Bagha’s bewitching music, rooted deeply in the Indian classical and folk school, has halted a war and, ten years later, brought an end to the tyranny of King Hirak.

But what I veritably seek to investigate in this section is whether we can consider Goopy and Bagha as revolutionary figures or not. To answer this, we first need to decipher a few dialectics encoded in the film, especially the ones that functioned as an impelling rationale behind our protagonists’ urge to halt the colossal Halla troops from invading Shundi. It is (primarily) because, on the condition of saving his kingdom from being ravaged by the Halla army, the king of Shundi promised to betroth his daughter to one of our protagonists. Therefore, driven by such fetishism (considering the princess as something of a commodity to win), they fail to offer us a scope to recognize their efforts as ‘noble’ or ‘honest.’ Perhaps understanding such incongruities in the bildung of Goopy-Bagha, Ray introduced the character of Udayan Pundit in the sequel.

The sequel, Hirak Rajar Deshe, stretches Goopy-Bagha’s journey but also contradicts its prequel in many aspects. The film delineates, symbolically, the fate of a postcolonial nation-state, falling prey to the hands of a totalitarian authority. In such regimes, one often witnesses the authority brainwashing the proletariat by imposing a monolithic train-of-thoughts (e.g., religion, racial supremacy, cultural supremacy, etc. al.), hacking democracy and banishing the dissenting voices from the state. All these themes and their inevitable consequences are sharply portrayed in the film.

Udayan Pundit has been banished from the kingdom of Hirak for running a ‘Pathsala’ (school). Instead of fleeing, he seeks refuge in a tenebrous cave and secretly plans to organize all his class allies to overthrow the dictator from his throne. It is from Udayan Pundit that Goopy-Bagha learn the tactics of a revolution. Udayan, in his long-grown beard and dialogues, echoes the ideals of Che Guevara (though he doesn’t take the path of an armed revolution).

When the naïve and illiterate Goopy boasts before him, asserting that he and Bagha can halt any uprising, Udayan explains to them why, sometimes, we need an uprising to rectify the wrongs of our society. He teaches them to organize the labourers, agrarian workers, and the state army before countering the dictator, and through his tactics, which Goopy-Bagha implements, we see how an authoritarian tyrant becomes vulnerable in front of an organized force. So, the conclusion to this section can be drawn by stating that it is the cohort of Goopy, Bagha and Udayan Pundit that can be entitled as revolutionary because the rationale behind their collective effort is truly noble and honest, but Goopy-Bagha on their own are mere simpletons, lacking the necessary erudition to organize a revolution, and are mostly keen on gaining private profits.

Goopy Bagha’s unabashed patriarchal views

Class consciousness, in the context of India, has always been clouded by firmly rooted caste discrimination, with patriarchy and racism as its natural allies. Goopy and Bagha’s worldview, especially their tendency to recognize the presence of women as mere commodities, aligns perfectly with the Indian tradition of casteist patriarchy.

Bagha, coming from a lower caste family, has an almost intangible desire (or a fantasy) to marry a princess, which he also implants in Goopy’s mind. This fantasy of Bagha is actually rooted in his desire to discard his own class position, as marrying a princess would inevitably improve his living standards or vice versa. So, the princess exists in Bagha’s mind merely as capital which he seeks to exploit for gaining a private profit.

When Goopy-Bagha notices Monimala, the princess of Shundi, for the first time, Goopy mistakes her for a ‘Jhi’ (maid) but is immediately corrected by Bagha, who remarks that maids’ complexions cannot be this fair. As the princess takes her leave, Goopy, with his goofy gesture, says: “Pakhi Ure Gelow” (‘The bird has flown’). Objectifying women as birds is a popular masculine view, which indirectly suggests that women are living beings whose sole duty is to entertain men and must be caged.

And they indeed follow this conventional patriarchal line. Once the princesses of Shundi and Halla become their wives, they demarcate their wanderings within the palace. We learn this from the opening sequence of “Hirak Rajar Deshe,” where Goopy-Bagha reveals, through their song, that their beautiful and efficient wives stay at their homes and take care of their children. Thus, I shall argue that Goopy and Bagha cannot be regarded as the ideal (or purest) representatives of socio-political resistance because they have never been seen incorporating women’s participation in any of their missions; moreover, they limit them to the confines of the house.

Manipulating technology, alienating technicians

The two films under discussion here have their roots in two different traditions. GGBB is firmly rooted in the folklore tradition, while “Hirak Rajar Deshe” has its roots in symbolism. Since GGBB is rooted in folklore, its phantasmagorical narrative occasionally takes a break from the burden of explaining everything logically. For example, we are not told from where ‘Barfi’ – the magician – comes, we don’t know how exactly he gained his magical powers, and in how many instances the authority of the Halla kingdom manipulated his esoteric talent.

Whereas, in “Hirak Rajar Deshe”, king Hirak himself explains that the scientist Gobochandra Gyantirtha Gyanchandra Gyanambudhi Gyanathuram, seven months ago, has arrived at the land of Hirak from Jambudvipa and self-proclaimed that there is nothing in the world of science that he is ignorant of. The scientist asked the king to arrange a laboratory for him and took seven lakh rupees in advance, promising that his inventions would make the king’s enterprises a children’s game. By pasting and burning several metals and limbs of different animals, the scientist invented a machine capable of controlling anyone’s brain, provided a suitable mantra for the target is inserted into the machine. The king exploits this invention by using it against mine-labourers and agrarian workers, and he devises plans to target students and their teachers next, which, however, he fails to succeed in carrying out.

The difference between Barfi and the scientist Gobochandra lies in their different modalities of obeisance to the state. While Barfi is seen to be a nonchalant mere state machinery who is untroubled by how the state manipulates his formulas, the scientist Gobochandra actively takes part in the climax sequence by inserting a mantra into the machine to wash the king and his allies’ brains. He needs to be seen as an alienated inventor who has grown tired of seeing the state’s manipulation of his inventions. Perhaps that is why he becomes furious when Goopy-Bagha asks, Whose side are you on, and he declares, “I’m alone! I live all by myself.”

If compared, these two characters, through the means of their socio-political existence, and if the imagery of their countenance is studied closely, one might decipher the subtle dictum that science (even in the form of magic), by itself, cannot take a side. Rather, it depends on the user(s) and their intentions in utilizing it.

Based on the propositions which I propounded in this article, I would like to argue that, to understand the poetics and politics of Goopy-Bagha’s deeds, one needs to assess their bildung, which is expanded in two instalments (two films). What led me to engage critically with this duology is a handful of oddities that I noticed in the popular discourse. To conclude this piece, I must say that while using two fictitious characters to cope with or counter a national/regional/global crisis, one must keep in mind the incongruities inherent in them, so that they can avoid those incongruities blending with their anthems of resistance.

![Ozu’s Equinox Flower [1958] : The Autumn of the Patriarch](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Equinox-Flower-768x575.jpg)