Pixar Animation Studios began as a trailblazer in the world of animation movies with the release of Toy Story in 1995—the first fully computer-animated feature film. But Pixar didn’t stop at innovation; it steadily built a reputation for emotionally intelligent storytelling, rich visuals, and deeply human themes, even when its characters were toys, monsters, or anthropomorphic feelings. Across nearly three decades, Pixar has told stories that echo childhood wonder and adult melancholy in equal measure. These films have become staples of global popular culture, often sparking philosophical debates and personal reflections.

Pixar’s filmography spans coming-of-age tales, existential dilemmas, speculative futures, and deeply rooted cultural stories. Themes like memory, identity, grief, legacy, and belonging surface repeatedly. Politics, too, often weaves subtly through its narratives—whether it’s environmental degradation in WALL-E, workplace equity in Monsters, Inc., or immigration metaphors in Elemental. Yet, in recent years, Pixar’s position has shifted. Some viewers feel disconnected from its latest outputs, citing a tonal drift or franchise fatigue. Others see evolution as necessary experimentation.

Personally, I have been so attached to the Pixar universe during my formative years that it’s hard for me to digest that the studio isn’t the same anymore. However, the little stories that it spur up every now and then – their latest film “Elio” for instance – have always managed to make me take away something personal and fruitful home. In accordance to that, I’ve decided to explore each Pixar movie released to date—examining its premise, the emotional or philosophical core it taps into, the animation style and storytelling decisions, the audience it connects with, and the broader cultural or political context it inhabits. I have also tried to rank them on the basis of my own comprehension and liking of what these stories are trying to say, and how successful they are in saying it.

Please be aware that this is a very personal opinion and should not be a representation of the quality of the films in the Pixar canon because they will most definitely have a different impact on the one’s watching it.

29. Lightyear (2022)

Director: Angus MacLane

Honestly, Lightyear didn’t work for me—for two very clear reasons. First, it lacked any real sense of thrill or emotional pull. For a film that was supposed to be the in-universe blockbuster that inspired Andy’s love for Buzz Lightyear in the Toy Story movies, it felt flat, distant, and hollow. The pacing dragged, and the story struggled to hook.

Second, Chris Evans voicing Buzz didn’t bring the energy or weight the character needed. Buzz felt like a caricature of himself, missing the humor, depth, and charisma we knew of. It felt like a misstep—not just in casting, but in how the character was handled. It’s tough not to see it as Pixar banking on brand recognition rather than crafting something meaningful.

The film might’ve looked sleek—space, robots, time loops—but the emotional beats didn’t land. The plot was more about ideas than connection, and the supporting characters, though diverse and well-meaning, didn’t have enough time to become memorable. More than anything, Lightyear felt like a commercial product. Not a story. Not a film that came from a place of curiosity or emotion. Just a studio decision trying to expand a franchise that didn’t need expanding. And in doing that, it missed what made the original Buzz iconic—not the suit or the catchphrases, but the heart underneath it all.. It asks what it means to live with your choices—and whether heroism is defined by action or adaptation.

28. Cars 2 (2011)

Director: John Lasseter

Cars 2 takes a hard turn from the introspective Americana of its predecessor and steers directly into international espionage. Lightning McQueen is back, but this time the spotlight shifts to Mater, who inadvertently gets caught up in a global spy mission while accompanying McQueen to a series of Grand Prix races.

The sequel trades small-town charm for globe-trotting spectacle—complete with high-speed chases, secret agents, and elaborate sabotage plots. While the visuals remain impressive, especially in rendering global backdrops like Tokyo and the Italian Riviera, the tonal shift is jarring. The heart and stillness of the first Cars film give way to kinetic energy and spy parody. However, the decision to center the narrative on Mater’s accidental heroism means sidelining the more grounded character work of McQueen and his growth from the previous film.

Michael Caine joins the voice cast as British spy Finn McMissile, adding a dose of Bond-like charisma, while Emily Mortimer voices Holley Shiftwell. Their presence underscores the film’s playful riff on espionage tropes, but the thematic depth typical of Pixar’s best work is largely absent. Cars 2 also marked the first major critical bashing that the studio had received, even though it wasn’t the first time they tried to build on a popular franchise.

27. Cars 3 (2017)

Director: Brian Fee

Cars 3 takes a deliberate step back from the high-octane spectacle of Cars 2 and returns to the franchise’s original emotional lane. Lightning McQueen (Owen Wilson) is no longer the rookie—he’s the aging legend, watching newer, faster racers like Jackson Storm dominate the track. The story begins with a crash, both literal and existential, that forces McQueen to confront the inevitability of change.

This installment is about legacy and about knowing when to fight, when to evolve, and when to step aside. McQueen’s struggle is less about reclaiming his title and more about finding new purpose in a world that’s moved on. That tension—between relevance and reinvention—forms the emotional spine of the movie. Cruz Ramirez (voiced by Cristela Alonzo), a car who never saw herself as a racer, enters as McQueen’s spirited, tech-savvy trainer and becomes the one who carries the baton forward. Over time, their dynamic shifts: from mentor-mentee to something more balanced, even symbolic.

The animation is notably polished. The stormy beach scenes, the reflections off polished hoods, and the final race under bright lights—all showcase Pixar’s technical range. But the visuals never outpace the story. Cars 3 isn’t flashy or groundbreaking and it doesn’t even try to be. Instead, it’s a quiet meditation on mentorship, humility, and how stepping back can sometimes be a form of moving forward.

26. Elemental (2023)

Director: Peter Sohn

Elemental is set in Element City, where fire, water, earth, and air live together—but not without barriers. Ember, a fire element raised in the immigrant neighborhood of Fire Town, is expected to take over her family’s store. When a plumbing accident leads her to Wade, a water element and city inspector, her world begins to shift.

For me, Elemental was also quietly triggering. There’s an undercurrent of gender dominance, the trope of the emotional male savior, and a manic-pixie energy placed onto a protagonist who otherwise carries the weight of the story. Ember wants to make her own decisions, but she’s constantly seen through the lens of someone else’s understanding—often Wade’s, who ends up explaining feelings to her, even when she’s the one going through them.

The story taps into something broad—immigration, cultural inheritance, and intergenerational pressure—but its execution sometimes slips into overly neat binaries. Ember’s personal struggle to balance self-worth with family duty is resonant. Yet, the emotional navigation often feels framed by someone else’s insight rather than her own voice leading the way. It’s beautiful and well-intentioned, but I couldn’t help wanting it to trust Ember more—as a protagonist, as a woman, and as someone capable of carrying the emotional arc without the need to be mansplained. Elemental works in parts, but it also leaves behind the question: why does a story built around difference still fall into familiar storytelling traps?

25. Elio (2025)

Directors: Adrian Molina, Domee Shi, Madeline Sharafian

Elio is an extremely cute movie about a bright young boy who, after losing his parents, moves in with his aunt—who also happens to be a space marshall. But Elio doesn’t feel like he belongs on Earth. He believes the intergalactic world is where he truly fits in, and he works toward connecting with aliens, hoping they’ll take him to a place where he feels wanted.

The story is about understanding your place in the world through a child’s eyes. With adults too busy doing “important” things, a child with no sibling or parent can often feel isolated. Elio taps into that—loss, loneliness, and the little ways children try to make sense of it all. The animation is full of color and life, and the tone is light enough to make you giggle, even when the themes are heavy. Elio, with all his “wokeness” and intelligence, tries to fix his immediate environment in ways that feel entirely like something a child would do—creative, hopeful, a little messy, but full of heart.

When his efforts to meet the aliens actually work, you’re surprised and hopeful along with him. That moment opens up the rest of the film beautifully. For me, the story also felt political in an interesting way. In one scene, Elio has to present himself as the leader of planet Earth to avoid conflict with an egotistical alien leader. And even though he’s just a child, he does it with confidence and clarity. It feels like a quiet nod from Pixar that the future—peace, empathy, leadership—might just belong to kids who feel everything deeply and aren’t afraid of being vulnerable.

24. A Bug’s Life (1998)

Directors: John Lasseter, Andrew Stanton

Pixar’s sophomore feature steps out of the toybox and into the dirt. A Bug’s Life zooms in on an ant colony living under the weight of a yearly shakedown by a gang of grasshoppers. Flik, a well-meaning misfit inventor, decides he’s had enough—and sets out to find help. What he returns with isn’t a band of warriors but a down-on-their-luck group of circus bugs. What unfolds is a comic misadventure that becomes a story of courage, misjudgment, and collective action.

Though it doesn’t carry the same emotional depth as later Pixar movies, A Bug’s Life shines in world-building and metaphor. Inspired in part by Aesop’s fables and the narrative structure of Seven Samurai, the film disguises a story of uprising and solidarity within the vibrant lens of a children’s adventure. The animation is noticeably more ambitious than Toy Story, with sweeping natural landscapes, sunlight filtered through blades of grass, and complex crowd sequences. The film leans into physical comedy and timing, bolstered by a playful score and a voice cast that includes Dave Foley, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, and Kevin Spacey as the menacing Hopper.

While it might not be the most discussed Pixar movie today, A Bug’s Life holds its place as a movie that subtly introduces children to the idea of resistance, leadership, and the value of community. It’s a story about the smallest creatures finding strength in numbers—and in themselves.

23. Onward (2020)

Director: Dan Scanlon

Onward builds its world on a simple reversal—what happens when magic fades, not because it’s gone, but because people stopped needing it. The setting is a modern-day fantasy suburb where unicorns are pests and spells have been replaced by appliances. Within this quiet collapse of wonder, we meet two elf brothers: Ian and Barley Lightfoot.

Ian, voiced by Tom Holland, is awkward, cautious, and uncertain of himself. Barley, voiced by Chris Pratt, is loud, impulsive, and obsessed with the old ways—maps, quests, and enchanted history. On Ian’s 16th birthday, the brothers receive a magical gift from their late father: a spell that can bring him back for a single day. It works—but only halfway. The lower half of their father appears. Time is limited. So they set out to find the missing piece, literally.

What follows is a road movie across forgotten parts of their world. As the journey unfolds, Ian keeps track of all the things he never got to do with his dad. By the end, that list becomes something else entirely. Onward doesn’t make a spectacle of its grief. It lets it rise gradually through small gestures, near-misses, and realizations that shift everything. What the film ultimately offers isn’t a reunion, but clarity. It reframes presence. Ian doesn’t meet his father. But he sees who’s been there all along.

22. Soul (2020)

Directors: Pete Docter, Kemp Powers

Soul begins with a question that Pixar hadn’t yet asked so directly: what makes a life meaningful? Joe Gardner, a middle school band teacher and jazz pianist, is offered the chance of a lifetime—to play with a legendary musician. But before the gig, he falls into an open manhole and finds himself in the “Great Before,” a liminal space where souls are shaped before birth.

The film doesn’t follow the traditional arc of achieving a dream. Instead, it asks whether the dream itself is what gives life meaning. Joe teams up with 22, a soul who has never wanted to live, and through their unlikely partnership, the story slowly pivots. What Joe thinks is the purpose is reframed into presence.

The film speaks more directly to those stuck in loops, questioning time, and wondering what they’ve missed. Joe’s journey is not about returning to life for a second chance at glory. It’s about seeing what was already there. The story has strong existential urges — something that Pixar has not explored with their movies ever, seeing how they were mostly focused on kids, but this film, helped bring in the more mature audience to trust Pixar again. The animation contrasts two worlds: the tactile, bustling New York and the fluid, minimalist design of the soul world. Jon Batiste’s jazz compositions and Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’s ambient score layer the film with emotional texture.

21. Monsters University (2013)

Director: Dan Scanlon

A prequel to Monsters, Inc., Monsters University tracks Mike Wazowski and James P. “Sulley” Sullivanback to their college days—before they were partners, before they were friends. It’s a story about ambition, failure, and the slow, messy process of learning that talent alone doesn’t guarantee success.

Mike, ever the planner, dreams of becoming a top scarer and believes hard work will get him there. Sulley, coasting on natural ability and a famous family name, believes less in discipline and more in instinct. When both are kicked out of the elite Scare Program, they’re forced into an uneasy alliance, joining the school’s least respected fraternity to compete in the campus Scare Games.

The emotional arc here is more understated than in Monsters, Inc.—but quietly poignant. It’s not about defeating a villain, but confronting the truth that sometimes you won’t get what you want, even if you do everything right. That lesson, wrapped in campus hijinks and monster humor, lands differently depending on who’s watching: kids see the value of teamwork; adults see the inevitability of recalibrating dreams.

The animation leans into vibrant colors and collegiate iconography—banners, dorm rooms, libraries—remixed through a monster lens. While it doesn’t hit the same emotional peaks as its predecessor, Monsters University offers something valuable: the idea that your path might not look the way you imagined, and that success isn’t always about being the best. Sometimes, it’s about finding where you truly belong.

20. The Good Dinosaur (2015)

Director: Peter Sohn

The Good Dinosaur opens with a simple but intriguing premise: what if the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs had missed Earth altogether? In this alternate history, dinosaurs continue to live and evolve, forming their own agrarian societies. At the center of the story is Arlo, a timid young Apatosaurus separated from his family and forced to journey home through untamed wilderness. Along the way, he forms an unlikely bond with a feral human boy he names Spot.

The narrative is familiar—a classic survival and coming-of-age arc—but it’s the emotional tone that defines it. Arlo’s path is less about conquering fear and more about understanding it, navigating loss, trust, and resilience in a world that often feels overwhelming. The film’s visuals are among Pixar’s most photo-realistic from the landscapes—towering mountains, stormy rivers, and sweeping plains—all are rendered with a painter’s eye for light and scale, while the characters retain stylized features that contrast against the natural backdrops.

Though The Good Dinosaur didn’t leave the cultural imprint of Pixar’s other hits, its gentle rhythms and emphasis on emotional truth offer a quieter, more contemplative entry in the studio’s filmography.

19. Toy Story 4 (2019)

Director: Josh Cooley

If Toy Story 3 was about letting go, Toy Story 4 asks what happens after you do. The toys are now with Bonnie, a new child, and Woody finds himself increasingly without a role. When Bonnie creates Forky—made from a spork and pipe cleaners—Woody sees a new purpose: keep Forky safe.

The film is centered on a deeper question: who are you when you’re no longer needed? Woody’s sense of duty, once rooted in Andy’s love, now exists without a clear anchor. His encounter with Bo Peep, now independent and self-sufficient, further challenges his worldview. Their dynamic brings in a quiet maturity—the clash between loyalty to the past and embracing reinvention.

The concluding film has a very precise and tactile quality that makes you focus on porcelain cracks, carnival lights, and dust on antique shelves. New characters like Duke Caboom (Keanu Reeves) and Gabby Gabby (Christina Hendricks) add humor and melancholy and with Gabby (which may seem like a villain), turns out to be a character searching for validation, giving the film another shade of longing.

Explore More: Oscars 2020: Ranking The 2019 Best Animated Feature Nominees

18. Cars (2006)

Director: John Lasseter

Pixar slows things down with Cars, a movie that trades the high-tech or high-concept settings of its predecessors for a dusty town off Route 66. At its center is Lightning McQueen (Owen Wilson), a rookie race car obsessed with speed, fame, and winning. When he gets stranded in Radiator Springs—an aging town bypassed by progress—he’s forced to confront everything he’s been speeding past: relationships, responsibility, and reflection.

While the idea of anthropomorphic vehicles may alienate some, the film gently weaves a story about deceleration in a culture of acceleration. Radiator Springs becomes a metaphor for places and people forgotten by time. For children, it’s a world of vibrant characters, racetrack drama, and comic relief through Mater (Larry the Cable Guy), the rusted tow truck. But adults will find a meditation on burnout, relevance, and the cost of ambition that never pauses.

The animation replicates Americana with reverence. Sun-drenched highways, chrome reflections, and desert backdrops evoke a sense of nostalgia. The design of the cars—each with human expressions molded into their grills and eyes—strikes a careful balance between playfulness and visual coherence. While it may not rank among Pixar’s most emotionally complex films, Cars offers something different: a quieter contemplation of what happens after the spotlight fades, and the beauty of rediscovering purpose not through acceleration, but stillness.

17. Turning Red (2022)

Director: Domee Shi

Turning Red centers on Meilin “Mei” Lee, a 13-year-old Chinese-Canadian girl navigating adolescence, expectations, and the onset of a very unusual family trait—when emotions run high, she transforms into a giant red panda. The film doesn’t use metaphors gently. It leans into it. Mei’s transformation is messy and awkward, mirroring the chaos of puberty and identity. At its core, the story is about generational expectations. Mei wants to carve her own space between tradition and independence, family loyalty and personal desire.

To me, Turning Red is a bold film, especially for Pixar. It openly addresses femininity, emotional chaos, and bodily changes in ways that 90s kids rarely saw in animated stories. The idea of an adolescent girl navigating her growing identity while trying to meet family expectations is complicated and long overdue. That said, while the film does break new ground, I wish it had pushed further. The narrative often stays safe, leaning into the specifics of one experience without opening up enough space for other genders to resonate equally. It also doesn’t help that it is paced like a cannon ball, not allowing its more important aspects to hold ground. The emotional truth is there, but it could’ve been sharper, broader, and less concerned with playing it safe.

The animation style breaks from Pixar’s usual realism, borrowing from anime and 2000s pop culture. Movement is exaggerated. Emotions are heightened. It fits the age and world of its protagonist. Sandra Oh voices Mei’s mother, Ming, with restraint and tension that slowly softens. The soundtrack, featuring original boy band songs, places the film firmly in its era, but the emotional beats remain universal.

Also Read: Turning Red (2022) Movie Review

16. Luca (2021)

Director: Enrico Casarosa

Luca is a coming-of-age story set on the Italian Riviera, where sea monsters live beneath the waves, watching humans from afar. Luca, a young sea creature, ventures onto land and discovers that out of water, he takes on human form. What begins as curiosity becomes friendship, freedom, and a summer of change. With his friend Alberto, Luca explores the town of Portorosso, hiding their true identities as they dream of buying a Vespa and traveling the world. The film captures a brief, transformative phase of childhood—the moment when the world feels both wide and reachable, and identity is still fluid.

There is no central villain in Luca, no dramatic twist. Instead, tension arises from secrecy and the fear of rejection. The sea monsters’ need to hide parallels many forms of difference—cultural, emotional, personal. Children see an adventure and a bond. Adults might see the ache of outgrowing innocence, and the silent costs of hiding who you are. The animation draws inspiration from hand-drawn textures and soft pastels. The sea is rich with movement; the land, sun-drenched and grounded. The town feels lived-in without calling attention to its realism. The score by Dan Romer complements the lightness without undercutting the film’s emotional undercurrent.

While readings of the film have gone in several directions, director Enrico Casarosa once shared that a romantic possibility between Luca and Alberto was considered during development. But the focus ultimately remained on their pre-adolescent friendship—an emotional closeness that didn’t need romantic framing to feel intimate or real. Had they leaned into that queer narrative, it might’ve marked a bolder, more political move for Pixar, especially at a time when the studio has faced criticism for playing it safe.

15. Finding Dory (2016)

Directors: Andrew Stanton, Angus MacLane

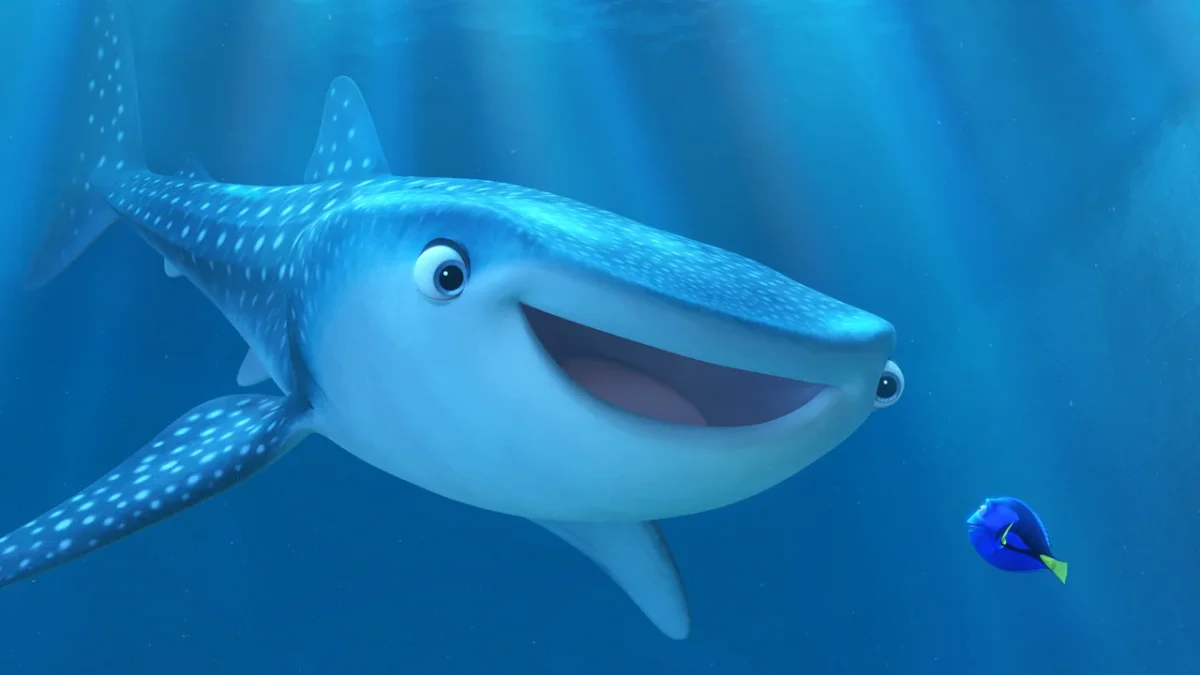

Finding Dory picks up a year after the events of Finding Nemo, but emotionally, it travels much further. Dory, the forgetful blue tang voiced again by Ellen DeGeneres, takes center stage this time—on a journey not just across the ocean, but into the foggy, scattered corners of her own memory. Unlike its predecessor, which moved with the urgency of a rescue mission, Finding Dory settles into something quieter: the slow search for self. The film introduces us to Dory’s backstory—her childhood, her parents, and how she came to be alone in the world. These pieces emerge in fragments, much like memory itself. As Dory swims through the Marine Life Institute in California, the pieces start falling into place—but not all at once.

What the film does well is tether a childlike sense of wonder to a deeper, often painful undercurrent: how do you hold onto yourself when you’re always forgetting? Dory’s optimism isn’t blind—it’s survival. That nuance gives the film its weight. The supporting cast—Ed O’Neill as Hank the septopus, Ty Burrell as Bailey the beluga, and Kaitlin Olson as Destiny the nearsighted whale shark—adds both humor and heart, each character carrying their own version of adaptation. These aren’t just sidekicks. They reflect parts of Dory’s internal world.

The film is rich and immersive as far as the animation is concerned—coral reefs, glass tanks, kelp forests—all rendered in the tactile, textured style Pixar had now perfected. And while it may not surpass Finding Nemo in emotional heft, Finding Dory stands on its own as a deeply empathetic portrait of living with difference, and the long road back to belonging.

You Might Be Interested In: 15 Great Films About Memory

14. Coco (2017)

Directors: Lee Unkrich, Adrian Molina

At its heart, Coco is about memory – not just what we remember, but how we are remembered. The story follows Miguel, a young boy from a shoemaking family in Mexico, who dreams of becoming a musician despite his family’s long-standing ban on music. His pursuit to learn about his ancestry, his passion, and his place in the world—takes him across the threshold into the Land of the Dead.

What begins as a spirited adventure across an afterlife soon becomes something more personal. The dead aren’t just spirits in Coco. They’re fragile, fading echoes who continue to exist only as long as someone remembers them in the living world. The concept of the “final death”—when the last memory of you disappears—is one of the film’s most affecting ideas. The story’s emotional fulcrum arrives with the song “Remember Me,” stripped of its performance value and reduced to a lullaby between a fading man and a little girl who once loved him.

Anthony Gonzalez voice as Miguel has a natural charm, while Gael García Bernal’s performance as Héctor offers deep humor. The film’s visual language includes intricate detailing, such as papel picado, ofrendas glowing in candlelight, and bridges of petals. Coco doesn’t traffic in nostalgia but builds a space where identity is an inheritance and memory is resistance.

13. Inside Out 2 (2024)

Director: Kelsey Mann

Inside Out 2 returns to the mind of Riley, now a teenager. With adolescence comes new emotions—Anxiety, Envy, Embarrassment, and Ennui—entering the headquarters where Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear, and Disgust once ran things without competition. The sequel picks up where the first film left off—gently challenging the idea that emotional balance is something that can be maintained. Instead, it shows how quickly things shift when your sense of self begins to fracture, expand, or contradict itself.

Anxiety, voiced by Maya Hawke, takes the lead—not as a villain, but as a presence that believes she’s helping. The film’s strength lies in showing how different parts of ourselves compete for control, especially when we’re still figuring out who we are. Visually, the film continues to experiment with abstract spaces—long-term memory, imagination, belief systems—now layered with teenage volatility. However, it doesn’t repeat the first film’s structure, rather it evolves it.

12. Brave (2012)

Directors: Brenda Chapman, Mark Andrews

Set against the sweeping Highlands of medieval Scotland, Brave is Pixar’s first fairy tale and its first film led by a female protagonist. Merida (Kelly Macdonald) is a skilled archer and a rebellious princess resisting the traditions of royal marriage imposed by her mother, Queen Elinor (Emma Thompson). When Merida seeks to change her fate, a magical mishap transforms her mother into a bear, forcing the two to confront their strained bond.

Unlike Pixar’s more ensemble-driven films, Brave is anchored by a mother-daughter dynamic. The emotional tension lies in miscommunication across generations—how expectations, love, and fear often disguise themselves as control. Visually, the film is one of Pixar’s richest—lush landscapes, glowing will-o’-the-wisps, and the textured depth of Merida’s wildly animated red hair stand out. The animation team’s attention to natural light and atmosphere creates a world that feels mythic without being overly fantastical.

Patrick Doyle’s Celtic-infused score adds a sense of place and emotional sweep, and Julie Walters lends her voice to the eccentric witch whose spell sets the plot in motion. While Brave may not dive into existential questions like other Pixar movies, it marks a tonal and thematic shift—prioritizing personal relationships over grand ideas.

Watch This Space: All 24 Oscar-Winning Animated Movies Ranked from Worst to Best

11. Toy Story 2 (1999)

Directors: John Lasseter, Ash Brannon, Lee Unkrich

Toy Story 2 might have begun as a modest sequel, but it quickly outgrew that category. The film deepens the emotional and philosophical core of its predecessor, moving beyond the fear of being replaced to the fear of being forgotten entirely. When Woody is stolen by a toy collector, he discovers he was once part of a popular TV show, and that he’s now a valuable collectible. This revelation opens up a quiet, aching dilemma: is it better to be admired behind glass, or loved through wear and tear?

Jessie’s flashback sequence remains one of Pixar’s most affecting moments, portraying abandonment with delicate honesty. It’s a rare animated scene that invites silence from both children and adults—each understanding the feeling differently. The film also expands the ensemble dynamic, with Buzz stepping into a leadership role and new characters like Bullseye and Stinky Pete enriching the universe.

Visually, the animation improves in subtle but effective ways. The textures are smoother, the environments larger in scope, and the action scenes more ambitious—particularly the airport finale. The film balances humor with poignancy, giving space for existential reflection while never losing its pace. What Toy Story 2 manages so skillfully is transition: toys grappling with their life spans, kids growing up, and the audience maturing along with the franchise. It’s the moment Pixar confirmed it wasn’t simply in the business of sequels—it was in the business of storytelling with weight and consequence.

10. Monsters, Inc. (2001)

Director: Pete Docter

With Monsters, Inc., Pixar trades the suburban or natural landscapes of its earlier movies for an industrial labyrinth powered by childhood fear. The city of Monstropolis runs on energy harvested from children’s screams, and professional scarers like Sulley (John Goodman) and his one-eyed partner Mike (Billy Crystal) are at the top of the corporate food chain. But when a child named Boo accidentally enters their world, the system’s ethics are brought into sharp focus.

At its surface, the film plays with slapstick chaos, buddy comedy rhythm, and inventive creature design. But beneath that is a narrative about empathy in opposition to institutional fear. Sulley’s slow shift from top-scarer to protector is the emotional center, and Boo becomes more than a plot device—she’s a mirror through which adult characters, and viewers, reconsider what it means to care.

The animation is a leap forward, especially in Sulley’s fur—a technological milestone at the time. The design of Monstropolis is playful yet mechanical, filled with conveyor belts, factory doors, and cold storage—all rendered with detail that gives the world weight. Billy and Goodman elevate Mike and Sulley into one of Pixar’s most memorable duos, blending comic timing with unexpected emotional range. Monsters, Inc. doesn’t only ask what scares us—it asks why we let that fear guide entire systems. And in its answer, it shifts from screams to laughter, offering a radical idea: that joy, not fear, might just be the better way forward.

9. Incredibles 2 (2018)

Director: Brad Bird

Incredibles 2 picks up immediately where the first film ended, with the Parr family mid-battle against the Underminer. But rather than continue the same arc, the sequel pivots. This time, the spotlight shifts to Helen Parr, aka Elastigirl, while Bob stays home to manage the domestic chaos. It’s a smart reversal—less about new threats and more about new dynamics.

What unfolds is a meditation on shifting roles. Helen gets the call to action—not just in fighting crime, but in restoring superheroes’ public image. Meanwhile, Bob navigates a different kind of complexity: math homework, toddler tantrums, and the slow realization that fatherhood demands a different kind of strength. Especially when your baby, Jack-Jack, reveals unpredictable powers at every turn.

The film’s antagonist, Screenslaver, critiques media saturation and passive consumption—a thematic thread that runs quietly beneath the family hijinks. While not as emotionally tight as the original, Incredibles 2 still plays with the same ingredients: the strain between individuality and unity, secrecy and openness, power and accountability. The animation of the sequel is definitely sleeker and action scenes—especially a motorcycle chase with Elastigirl—are tightly choreographed showing off Pixar’s refined sense of motion.

8. Toy Story (1995)

Director: John Lasseter

Toy Story was not only Pixar’s first feature-length film, but also the first entirely computer-animated film in cinema history. This technological leap, however, is only one part of what made the movie groundbreaking. At its core, Toy Story is a story about purpose and identity, told through the rivalry and eventual friendship between Woody (Tom Hanks), a pull-string cowboy, and Buzz Lightyear (Tim Allen), a deluded space ranger who doesn’t know he’s a toy. The film explores how status and self-worth can be destabilized when change arrives—a theme that resonates across generations.

The film draws viewers in by placing them inside a child’s room from the toys’ perspective. Suddenly, the mundane becomes extraordinary. The animation, though basic by today’s standards, was revolutionary at the time. Textures, lighting, and movement were carefully calibrated to balance realism with playfulness. But it’s the writing that carries the film—witty, emotionally intelligent, and never patronizing. The storytelling carries a dual register. For children, the concept that toys come to life when humans leave the room is endlessly exciting. For adults, the narrative reflects anxieties around relevance, fear of being replaced, and the discomfort of change. Woody’s internal journey—moving from jealousy to acceptance—mirrors very real emotional transitions.

Toy Story’s screenplay—co-written by Joss Whedon, Andrew Stanton, Joel Cohen, and Alec Sokolow—is packed with humor and emotional depth, without ever talking down to its audience. The film was nominated for three Oscars and received a Special Achievement Academy Award for its pioneering animation, paving the way for future animated films to be taken seriously as both entertainment and storytelling.

Continue Reading: Top 10 Tom Hanks Films According To Rotten Tomatoes

7. Toy Story 3 (2010)

Director: Lee Unkrich

When Toy Story 3 arrived over a decade after the original, it carried the weight of a generation that had grown up with Woody, Buzz, and the gang. The film captures that sense of transition with remarkable clarity. Andy, now college-bound, must decide what to do with the toys that once meant everything to him. Through a series of missteps, the toys find themselves at Sunnyside Daycare—a place that appears welcoming but hides a strict, even cruel, hierarchy.

The film’s central tension doesn’t lie in escape or survival alone—it lies in purpose. If a toy’s job is to be there for a child, what happens when the child no longer needs them? Toy Story 3 lets that question hang over nearly every scene. The incinerator sequence—where the toys silently accept their fate—is perhaps one of Pixar’s most emotionally affecting moments, precisely because it offers no easy out until the very last second.

Visually, the film pushes boundaries in lighting, texture, and depth. Dust motes, aging plastic, and sun-streaked rooms evoke a quiet melancholy. While, for children, there’s adventure, humor, and a sense of triumph, on the other side, it’s a farewell ritual for those who grew up with the franchise. Andy’s decision to pass the toys to a new child—Bonnie—isn’t just a plot resolution; it’s a metaphor for aging, memory, and letting go.

6. Finding Nemo (2003)

Dirctor: Andrew Stanton

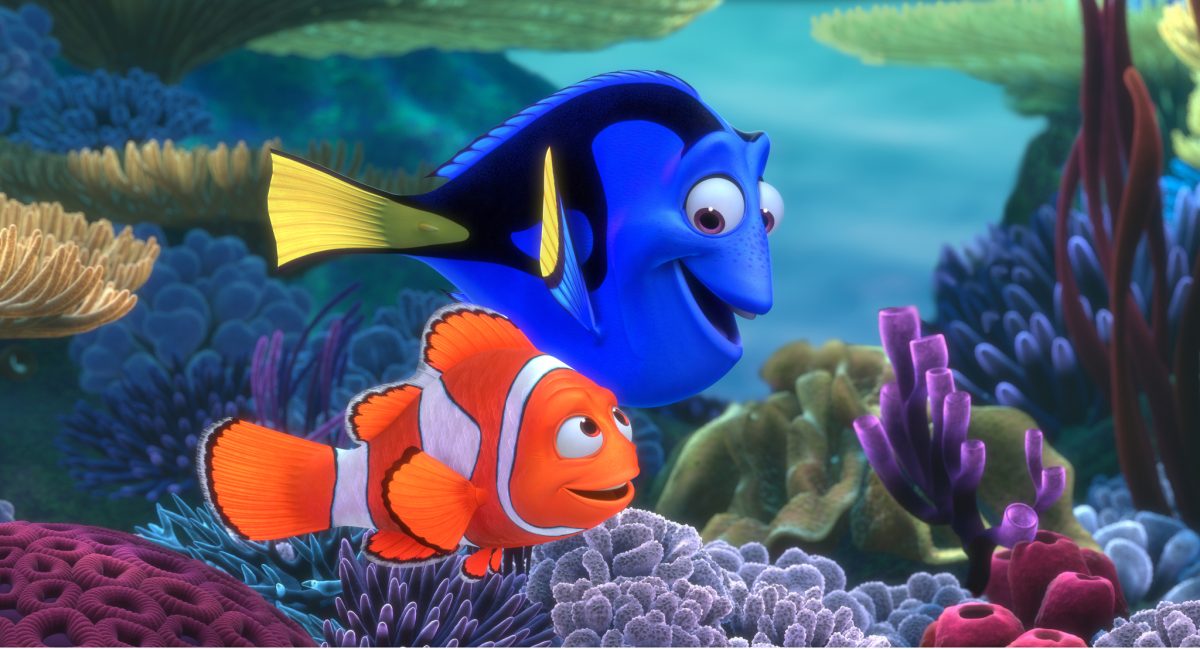

Beneath the vibrancy of coral reefs and bustling marine life, Finding Nemo is a story about fear—and how it shapes love. After losing his wife and most of their eggs to a predator, clownfish Marlin (Albert Brooks) becomes obsessively protective of his only surviving child, Nemo (Alexander Gould). But when Nemo is captured by a diver and placed in a dentist’s aquarium, Marlin must venture across the ocean to bring him home. The journey becomes as much about rescue as it is about release.

The film resonates with both sides of the parenting equation. For children, it’s a thrilling undersea adventure marked by colorful characters like Dory, the forgetful blue tang with a wide-open heart offering humor while embodying the film’s deeper theme: just keep swimming, even when memory fails. For adults, Marlin’s arc—his need to relinquish control and trust the world again—hits closer to home.

Visually, Finding Nemo set a new standard for aquatic animation. The way light refracts underwater, the layered textures of sea life, and the vastness of the ocean all serve the story rather than overshadow it. The sound design—whispers of water, distant echoes—helps establish a world that’s both immersive and isolating. At a time when animated movies rarely allowed for long silences or quiet reflection, Finding Nemo trusted its audience to follow currents of emotion without spelling everything out.

Dive In: 25 Great Dad Movies: Memorable Fatherhood Movies of The 21st Century

5. The Incredibles (2004)

Director: Brad Bird

Pixar’s first foray into the superhero genre leans more into family therapy than fantasy spectacle. The Incredibles opens in a world where superheroes have been forced into hiding, living under the weight of bureaucratic suppression and societal suspicion. Bob Parr, once Mr. Incredible (Craig T. Nelson), is now stuck in a cubicle, dreaming of his former glory while his wife Helen (Holly Hunter)—formerly Elastigirl—manages home life. Their children, each with latent powers, navigate the tensions of suppression and self-expression.

The brilliance of The Incredibles lies in how it folds genre tropes into a study of identity and repression. It’s not just about powers—it’s about what happens when you’re not allowed to be who you are. The story is equal parts domestic drama and mid-century espionage thriller, with a sleek retro-futuristic aesthetic that nods to Bond-era design and Cold War paranoia.

While children are pulled in by the action—supersuits, fast-paced battles, invisibility—the deeper currents speak to adult fears about purpose, disappointment, and the negotiation between personal ambition and collective responsibility. The villain, Syndrome (Jason Lee), is a former fan turned antagonist, a reflection of what happens when admiration curdles into resentment. Brad Bird’s script balances kinetic set pieces with crisp, character-driven dialogue. Michael Giacchino’s jazzy score further roots the film in a distinct tonal world. It’s a film that doesn’t shy away from moral gray zones—celebrating excellence without denying the costs of ego.

4. Up (2009)

Director: Pete Docter

Pixar opens Up with one of its most unforgettable sequences—a near-silent montage that compresses an entire lifetime of love, loss, and unfulfilled dreams into a few minutes. That opening sets the emotional tone for what follows: a story about Carl Fredricksen (voiced by Ed Asner), a widower who ties thousands of balloons to his house to fly it to Paradise Falls, fulfilling a promise he made to his late wife.

But the adventure doesn’t stay solitary. Carl is reluctantly joined by Russell (Jordan Nagai), a young Wilderness Explorer trying to earn his final merit badge. Their dynamic—crusty old man and optimistic child—evolves from irritation to interdependence. As they face sky dogs, a giant bird named Kevin, and the unmasking of Carl’s childhood hero as a villain, the film quietly explores what it means to live after loss.

The animation balances realism with fantasy: the South American landscapes are rendered with painterly detail, while the floating house becomes an unlikely symbol of grief in motion. Michael Giacchino’s score, especially “Married Life,” anchors the story in emotional restraint, allowing music to carry what words cannot. Up is about finding new life when the old one slips away. About how adventure doesn’t have to mean distant places—it can begin at the moment you decide to open your door again.

3. Inside Out (2015)

Director: Pete Docter

Inside Out turns inward—literally. The film follows 11-year-old Riley as she grapples with the emotional fallout of moving to a new city. But the real action takes place inside her mind, where Joy (Amy Poehler), Sadness (Phyllis Smith), Anger (Lewis Black), Disgust (Mindy Kaling), and Fear (Bill Hader) manage her emotional landscape like a control room.

Pixar’s innovation here is structural. The story doesn’t hinge on external conflict, but internal balance. When Joy and Sadness are accidentally ejected from headquarters, Riley is left without her core emotions, triggering a quiet spiral into detachment and confusion. The movie tracks Joy and Sadness as they journey through the memory banks, imagination land, and Riley’s subconscious—while Riley herself withdraws, struggles, and ultimately begins to process her feelings.

What’s most affecting is the film’s thesis: sadness isn’t failure. It’s connection. It’s care. That message lands with rare clarity, especially for older viewers who understand the relief of being understood, even in grief. The animation is vibrant and surreal, with colors, shapes, and physics shifting based on each mental realm. Michael Giacchino’s score, tender and wistful, underlines the emotional transitions with restraint. Rather than moralizing or simplifying emotional development, Inside Out accepts it as complex and layered. It’s a story about how growing up isn’t just about change—it’s about learning to carry joy and sadness together.

2. WALL-E (2008)

Director: Andrew Stanton

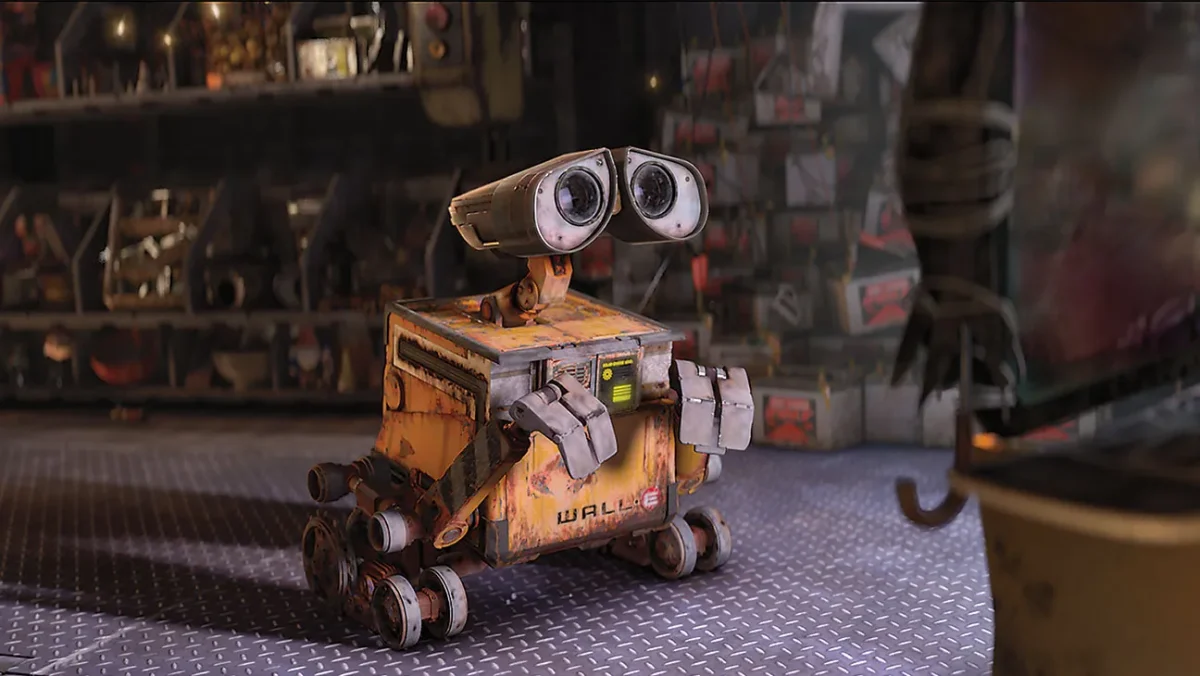

Pixar took its boldest narrative leap with WALL-E, centering the movie around a nearly silent protagonist and an Earth long abandoned by humanity. WALL-E, a lonely waste-collecting robot, spends his days cleaning up garbage and collecting relics of human culture. But everything changes when he meets EVE, a sleek, mission-driven robot sent to scan for signs of sustainable life. Their unlikely bond sets off a journey that stretches into space and confronts the detritus of consumerism.

Ben Burtt voices WALL-E using expressive beeps and whirs, creating one of Pixar’s most emotionally resonant characters with barely a word. The film’s first half plays like a silent-era romance, relying on visual storytelling, physical comedy, and mood-driven animation to capture emotion. Set against a backdrop of environmental collapse and passive human lifestyles aboard a space cruiser, WALL-E doesn’t preach—it imagines. Every shot of this animated movie feels composed, cinematic, and deliberate—proof that storytelling doesn’t require constant dialogue.

Thomas Newman’s score underscores the emotional weight of WALL-E’s solitude and the wonder of his awakening. More than a love story between two machines, WALL-E is about loneliness, purpose, and the rediscovery of care—in the smallest acts and the largest questions. It remains one of Pixar’s most daring films: contemplative, unsettling, and strangely hopeful. left to clean up a deserted Earth. It’s an indictment of consumerism, climate negligence, and passive living.

Full Story: Wall-E (2008) Movie Ending Explained

1. Ratatouille (2007)

Director: Brad Bird

Ratatouille takes an unlikely protagonist—Remy, a rat with a palate—and places him in the heart of French cuisine. What could’ve been a simple underdog comedy becomes a sharp, evocative story about talent, gatekeeping, and the pursuit of craft. Living in the sewers beneath Paris, Remy dreams not just of cooking, but of being taken seriously as someone with taste. Through a chance encounter, he finds himself controlling the hapless kitchen worker Linguini (voiced by Lou Romano) in a bustling restaurant once owned by the late great chef Gusteau.

Patton Oswalt voices Remy with wonder and precision, bringing internal conflict and excitement to life. The standout performance comes from Peter O’Toole as Anton Ego, the food critic whose final monologue reframes the film’s thesis: not everyone can become a great artist, but great art can come from anywhere. That idea lands gently with children, but adults will recognize its provocation—what qualifies someone to create, and who gets to decide?

The animation simulates flavor and movement with almost tactile detail. The kitchens sizzle and clatter with controlled chaos, while Paris glows just beyond the windows. Every dish Remy assembles becomes a visual and emotional crescendo, a quiet rebellion against the assumption that worth must come from the “right” background. Beneath its whimsy, Ratatouille asks serious questions about taste, access, and the value of hidden labor.