When “Sholay” was released on 15 August 1975, it was not an immediate box-office sensation. Critics initially dismissed it as overlong, derivative, and tonally uneven. Yet over time, the film not only reclaimed its investment but became the most enduring touchstone of Indian popular cinema. Its journey from critical indifference to cult immortality speaks to its unique position at the crossroads of genre experimentation, cultural hybridisation, and narrative audacity.

By marrying the stylised violence and moral ambiguity of the spaghetti western with the emotional excess and musicality of the Hindi “masala” tradition, Ramesh Sippy and the screenwriting duo Salim–Javed created what would later be celebrated as the quintessential “curry western.” The film resisted neat classification, functioning simultaneously as a revenge drama, buddy comedy, tragic romance, and action spectacle, thereby expanding the formal and thematic possibilities of Hindi mainstream cinema in the 1970s.

Beyond its technical and narrative innovations, “Sholay” became a language-defining event. Its dialogues entered everyday speech, its villain became a cultural archetype, and its characters inspired imitation, parody, and homage across decades. It challenged stereotypes about the Indian film hero, reimagined female roles in a male-dominated genre, and solidified the idea that Indian cinema could incorporate global influences without compromising its indigenous flavor.

Half a century later, “Sholay” remains a living text, quoted in political rallies, reframed in advertising campaigns, reinterpreted in scholarly discourse, and cherished in popular memory. Its 50-year legacy is not simply the survival of a film but the survival of an entire imaginative world that continues to resonate across generations, languages, and media.

The Birth of the ‘Curry Western’

By the mid-1970s, the spaghetti western had already left its mark on global cinema, yet Indian filmmakers had largely refrained from experimenting with its dusty landscapes, wide-angle gun duels, and morally ambiguous heroes. Ramesh Sippy’s “Sholay” transplanted this visual grammar into the Deccan plateau, reimagining Sergio Leone’s stylistic excesses through the lens of Hindi melodrama and folk narrative. The result was the “curry western”, a hybrid where cowboy hats met dhotis, six-shooters met sickles, and Ennio Morricone’s tense orchestral bursts found a local counterpart in R.D. Burman’s syncopated score.

The film situates Ramgarh in the rocky scrublands of the Deccan, a space that is both geographically real and cinematically mythical, a borderland where the writ of the state is tenuous, where the terrain itself becomes a moral testing ground, and where law must be reconstituted through community rather than enforced through distant institutions.

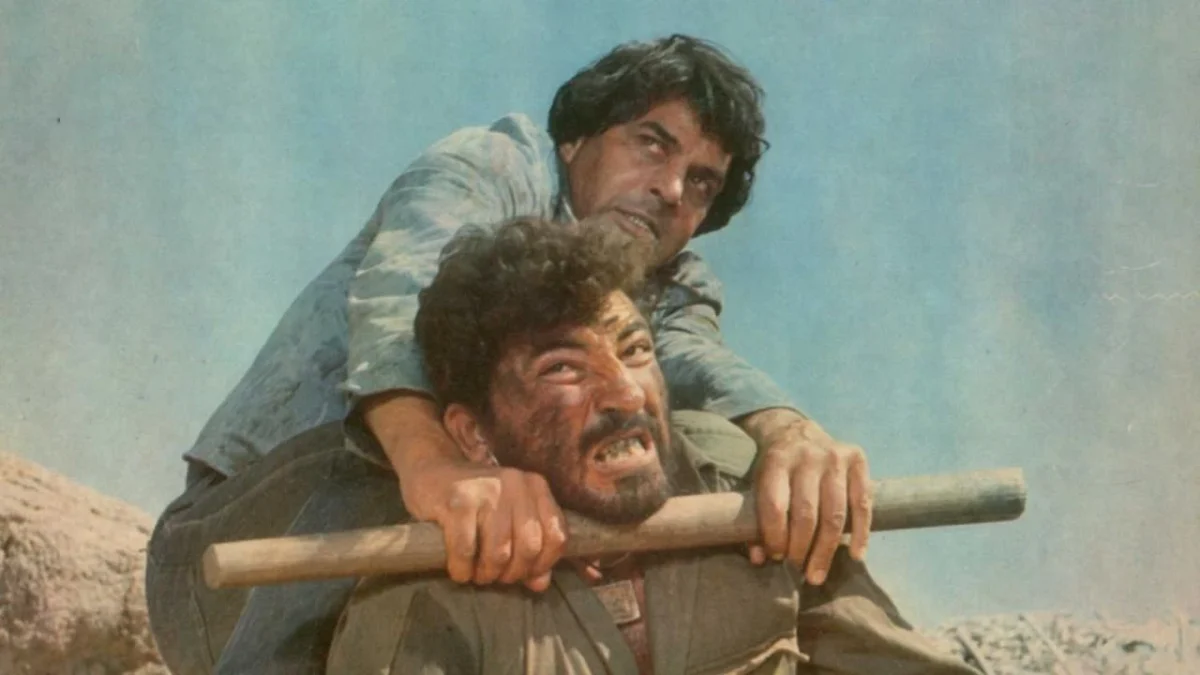

The iconography of the western – low-angle hero shots, prolonged standoffs, choreographed shootout – travels intact into “Sholay” but is quickly naturalised. Horses share space with tongas, the saloon is replaced by the village mela, and the familiar jangle of spurs is swapped for the clink of anklets and the rustle of dhotis. Even the train robbery, a staple of American western lore, is indigenised by placing it on the Indian Railways, transforming a global genre emblem into something deeply rooted in postcolonial Indian modernity. In this translation, the American outlaw becomes the Indian dacoit, and the sheriff becomes Thakur (Sanjeev Kumar), a maimed ex-policeman whose quest for justice bleeds into personal revenge.

If the American western often isolates the lone gunslinger, “Sholay” shifts the emotional axis to the buddy pairing of Jai (Amitabh Bachchan) and Veeru (Dharmendra). Their banter, shared songs, and moments of sacrifice transform the Western’s stoic individualism into a talkative, song-filled companionship, one that aligns perfectly with the Hindi masala tradition’s appetite for romance, comedy, and sentiment. R.D. Burman’s score similarly bridges two worlds: while it nods to the guitar twangs and whistled motifs of Ennio Morricone, it layers them with dholak beats, folk refrains, and full-throated melodies, creating a sonic frontier that alternates between tense silences and exuberant musical expression.

In “Sholay,” spectacle is never a hollow display; each set-piece – the train sequence, the siege of Ramgarh, the final showdown – is at once an action number and a narrative hinge. The choreography of distance, exposure, and cover remains faithful to Western traditions, but the stakes are reframed within a melodramatic ledger where loss and grief matter as much as victory.

Costume and gesture add another layer of localisation: Jai’s minimal denim, Veeru’s patterned shirts, Gabbar’s military fatigues, and Thakur’s stark black-and-white attire all function as visual shorthand for character and moral stance. Gabbar’s crouch, Jai’s sidelong glances, and Basanti’s animated speech patterns are as quotable as any line of dialogue, contributing to the film’s portability as a style that audiences could imitate, parody, and inhabit.

Perhaps most importantly, Sholay’s “curry western” preserves the moral ambiguity of its foreign inspiration without descending into nihilism. Jai and Veeru are ex-convicts whose loyalties are elective; Gabbar is charismatic even in cruelty; Thakur’s righteousness is shadowed by vengeance. Yet the film ultimately restores meaning: friendship, communal solidarity, and a stubborn sense of justice survive the chaos. In this way, the global genre is not simply transplanted but transformed, seasoned with local music, myth, humour, and emotional rhythms, until it is no longer a Western with Indian elements, but an Indian form in its own right.

Breaking Narrative Stereotypes

Before “Sholay,” the dominant strain of Hindi commercial cinema often followed a predictable arc: a romance-driven plotline set within a linear moral universe, with the hero embodying virtue and inevitably overcoming all obstacles. The genre boundaries were clear, and while “masala” films already blended song, comedy, and drama, they usually resolved with the reaffirmation of a simple moral order.

“Sholay” broke decisively from this formula. It did not merely blend genres, it integrated them into a cohesive, sprawling narrative that was part Western, part action thriller, part buddy comedy, part romance, part tragedy, and wholly cinematic spectacle. This multi-threaded construction allowed the film to shift tonal registers effortlessly, moving from a comic drunken serenade to moments of genuine pathos, from explosive action to intimate silences, without feeling disjointed.

Its protagonists, Jai and Veeru, were an equally radical departure from the virtuous hero archetype. They were not agents of the law or morally unblemished figures but ex-convicts hired for a dangerous mission. Their morality was situational, shaped by loyalty, friendship, and personal codes rather than institutional authority. This layered characterisation brought shades of grey into a cinematic space long accustomed to black-and-white morality, aligning more closely with the morally ambiguous figures of the spaghetti western than with Bollywood’s traditional hero.

Moreover, “Sholay” resisted the comfort of the all-powerful protagonist who triumphs through sheer charisma or physical might. The stakes in this story were deeply personal, rooted in loss, betrayal, and the need for redemption rather than in abstract notions of duty. Crucially, the film acknowledged that heroism could come at a cost. Jai’s death, arriving in the final act, was a moment of startling narrative boldness for a mainstream Hindi film.

This was not the symbolic, easily reversible death of melodrama but a permanent loss, underscored by its quiet, unceremonious depiction. It left audiences with a lingering sense of tragedy, reminding them that even in a world of stylised action and heightened drama, choices carried irreversible consequences. In doing so, “Sholay” expanded the emotional and thematic range of what a masala film could achieve, paving the way for a more nuanced engagement with heroism, sacrifice, and moral ambiguity in Indian cinema.

Villain as Icon: Gabbar Singh’s Cultural Takeover

Amjad Khan’s portrayal of Gabbar Singh marked one of the most significant turning points in the history of the Hindi film villain. Until “Sholay,” the mainstream antagonist was most often an urbane, suit-clad smuggler, a corrupt businessman, or a political power-broker—figures whose menace lay in their social influence and their ability to manipulate urban institutions. Gabbar was the antithesis of this template. He belonged not to the polished corridors of power but to the raw, lawless frontier of rural India. His cruelty was unvarnished, his authority enforced through fear, and his mannerisms were as feral as they were theatrical. The dust, sweat, and grime of the Chambal-like landscape clung to him as part of his identity, marking him as a product of the wilderness rather than the city.

What made Gabbar extraordinary, however, was not merely his brutality but the unpredictable texture of his personality. He was sadistic, but also possessed a streak of dark humour, delivering lines with a blend of menace and mocking playfulness. His casual cruelty, executing his own men for failure, tormenting his victims with sadistic games, was punctuated by an almost childlike delight in others’ fear. This oscillation between humour and horror made him more dangerous because it defied conventional emotional cues; audiences could never anticipate whether he would laugh or kill in the next moment.

Gabbar’s dialogues, crafted by Salim–Javed, were as sharp as bullets and quickly transcended the screen to enter everyday speech. Phrases like “Kitne aadmi the?” or “Jo darr gaya, samjho marr gaya” became linguistic shorthand for suspicion, bravado, or mockery, quoted in contexts far removed from cinema. In this way, Gabbar became not just a character but a cultural signifier, a point of reference in political speeches, advertising slogans, and casual banter.

Most strikingly, Gabbar’s charisma rivalled, and in some moments overshadowed, that of the film’s heroes. In a genre and era where the hero’s moral authority and narrative centrality were rarely challenged, “Sholay” allowed its villain to dominate the screen with equal, if not greater, magnetism. This inversion of moral centrality was not just a departure from formula, it signalled the early recognition that the anti-hero or charismatic villain could be a bankable figure in Hindi cinema. The result was a new archetype: the villain who could command fan followings, inspire mimicry, and achieve a form of immortality once reserved for heroes. In Gabbar Singh, Hindi cinema discovered that evil could be as enduringly iconic as good.

Women Beyond Decorative Roles

While “Sholay” is often remembered as a male-centric action epic, it quietly broke ground in its treatment of female characters, offering them greater agency, individuality, and narrative significance than was typical for mainstream Hindi cinema of the 1970s. In most commercial films of the period, women were idealised love interests, virtuous homemakers, or glamorous objects of spectacle, present to motivate the hero’s journey rather than to participate in it meaningfully. “Sholay” resisted this reduction by creating two sharply distinct female figures, each with her own moral and emotional texture, who contributed to the story’s thematic depth.

Basanti, played with verve by Hema Malini, is perhaps the most visible example. She is not simply a romantic accessory to Veeru’s character but a working woman with her own profession as a tonga driver, a role that positions her squarely in the public sphere, navigating male-dominated spaces with confidence.

Her chatterbox persona, comic timing, and resilience make her more than just a comic relief figure; she is a social connector, carrying news, facilitating encounters, and embodying a kind of grassroots agency that male heroes often take for granted. Basanti’s famous “chal Dhanno” sequences demonstrate not only her independence but also her physical courage, whether she is ferrying passengers through dangerous terrain or risking her life during Gabbar’s siege.

Radha, by contrast, inhabits the quiet spaces of the film, yet her presence is no less powerful. Played with restrained intensity by Jaya Bhaduri, Radha is a widow whose muted grief and stillness form an emotional counterpoint to the film’s bombastic action. Her relationship with Thakur, marked by shared loss and unspoken understanding, adds a layer of tragic intimacy to the narrative. Radha’s silence is not emptiness; it is a performance of dignity, resilience, and endurance in a world that has already taken much from her. In an era when female suffering was often expressed through high-pitched melodrama, Radha’s underplayed grief was a radical choice, demonstrating that quietude could be as expressive as spectacle.

Together, Basanti and Radha expand the film’s emotional and social range. They are not interchangeable symbols of love or virtue but distinct personalities who represent different modes of survival in a hostile world: one through vivacity, talk, and mobility; the other through stillness, introspection, and quiet strength. By giving space to both, “Sholay” challenged the stereotype of the female lead as a decorative placeholder, allowing women to participate in the film’s moral universe on their own terms. In doing so, it opened a subtle but important door for more layered female characters in the commercial Hindi cinema that followed.

Dialogues, Dialects, and the Linguistic Revolution

One of Sholay’s most enduring contributions to Indian popular culture lies in its language. Written by Salim–Javed, the dialogues did more than move the plot forward—they became a cultural currency, shaping how people spoke, joked, and even thought about cinematic characters. At a time when Hindi film dialogues tended toward florid, rhetorical flourishes or purely functional exchanges, “Sholay” delivered lines that were crisp, memorable, and deeply rooted in a colloquial Hindustani register. The writing balanced earthy rural idioms with urban wit, allowing the film to appeal simultaneously to audiences in small towns and metropolitan centres.

The linguistic choices also served to sharpen characterisation. Gabbar’s speech was jagged and abrupt, laced with mocking taunts that conveyed both his sadism and his self-assured dominance. Jai’s lines were spare and understated, reflecting his laconic nature, while Veeru’s were playful and expansive, brimming with mischief. Basanti’s rapid-fire chatter became a form of verbal acrobatics, a rhythmic performance of her extroverted personality. Even Radha’s silences were carefully scripted pauses, communicating volumes without a single spoken word. In this way, the dialogue was not just about what was said, but also about who was saying it, and how it fit their moral, emotional, and social position within the narrative.

Crucially, Sholay’s dialogues transcended the screen to become part of everyday speech. Phrases like “Kitne aadmi the?”, “Mujhe toh sab police waalon ki suratein ek jaisi lagti hain,” “Jo darr gaya, samjho marr gaya,” “Ek ek ko chun chun ke maaroonga… chun chun ke maaroonga,” “Iski saza milegi… barabar milegi” and “Basanti, in kutton ke samne mat nachna” slipped into the national lexicon, quoted in contexts ranging from school playgrounds to political rallies. This was not just mimicry; it was a sign of how deeply the film had embedded itself into the shared cultural imagination. The fact that these lines could be detached from their original context and still carry meaning or humour, speaks to the precision and universality of the writing.

In the decades since, few films have achieved this level of linguistic penetration. Advertising campaigns, comedy sketches, and public service announcements have repeatedly drawn on Sholay’s lines, trusting that the audience will catch the reference instantly. The film proved that dialogues could have a life beyond their immediate narrative function, becoming portable cultural artefacts in their own right. In doing so, it redefined the relationship between cinema and spoken language in India, demonstrating that a film’s verbal texture could be as influential and memorable as its images or songs.

The Cultural Impact: From Celluloid to Everyday Life

Over the past five decades, “Sholay” has moved far beyond the status of a successful film to become a central node in India’s cultural memory. Its imagery, characters, and dialogues have seeped into spaces far removed from cinema halls – politics, advertising, theatre, literature, and everyday banter. In many ways, it functions less like a single work of art and more like a shared myth, one that can be endlessly retold, referenced, and reinterpreted without losing its recognisability.

Politicians have invoked its lines to score rhetorical points in Parliament; advertisers have co-opted its characters to sell everything from detergent to motorcycles; and stand-up comedians, mimicry artists, and street performers have recreated Gabbar’s voice or Basanti’s chatter to instant applause. This portability is the hallmark of a true cultural phenomenon: the audience doesn’t just watch “Sholay”, they carry it with them, in their speech, humour, and mental imagery.

Its fashion cues also left an imprint. Jai’s minimalist denim shirts and Veeru’s patterned bandanas became emblems of rugged masculinity in the 1970s, while Gabbar’s patched fatigues and boots lent an oddly stylish edge to the archetype of the outlaw. Even Thakur’s stark black shawl over white kurta came to symbolise a mix of authority and personal tragedy. In an industry where costumes were often flashy and ornamental, Sholay’s sartorial choices worked as extensions of character psychology, further aiding their memorability.

The film’s musical score likewise transcended its original context. R.D. Burman’s themes became auditory markers, instantly recognisable to listeners even decades later. From the jaunty “Yeh Dosti” to the suspense-laden instrumental motifs associated with Gabbar, the music functions like a cultural trigger, evoking emotions, scenes, and even lines of dialogue without the need for visual accompaniment.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Sholay’s cultural impact is its cross-generational endurance. Viewers who first saw the film in its theatrical run have passed down its stories, songs, and catchphrases to their children and grandchildren. Newer audiences, encountering it through television reruns, streaming platforms, or meme culture, often find themselves quoting it without having watched it in full, a testament to how thoroughly it has permeated India’s collective consciousness. The film’s characters and situations have been remixed, parodied, and even politically reimagined, yet they remain instantly legible to audiences across regions, languages, and class divides.

In this way, “Sholay” is not just a product of its time but a continually renewable resource for Indian popular culture. Its durability lies in its ability to be both specific, rooted in the textures of 1970s rural India; and universal, tapping into timeless archetypes of friendship, revenge, courage, and villainy. Few films manage to retain their narrative and emotional potency while becoming so deeply woven into the fabric of everyday life, but “Sholay” remains a rare example where art, entertainment, and cultural memory converge seamlessly.

The Cinematic Language of Immortality

Sholay’s technical bravura, shot in CinemaScope, choreographed action sequences, slow-motion gunfights, and panoramic location shots, was unprecedented in Hindi cinema at the time. Sippy’s pacing alternated between meditative pauses and bursts of kinetic action, while R.D. Burman’s score used leitmotifs to bind the narrative emotionally. The film’s immersive world-building made Ramgarh as memorable as its characters.

Today, “Sholay” is more than a film, it is a palimpsest of Indian popular culture. It gave Bollywood its first true cult fandom, where viewers returned for repeat screenings, memorised dialogues, and identified with its moral universe. It remains endlessly referenced in memes, remixes, and homages. Crucially, it proved that Indian cinema could assimilate and localise global genres without losing its own idiomatic charm.

Half a century after its release, “Sholay” continues to stand as a towering landmark in Indian cinema, not merely because of its box-office success, but because it redefined what popular filmmaking could achieve. It fused the grammar of global genres with the ethos of rural India, gave moral ambiguity to heroes and magnetic power to its villain, and carved characters so indelible that they became part of the nation’s cultural vocabulary. Its songs, dialogues, and visual motifs remain as alive today as they were in 1975, reminding us that truly iconic cinema is not bound by time, it grows, adapts, and continues to speak to each new generation. In celebrating “Sholay” at fifty, we are not just honouring a film; we are acknowledging a living legend that still rides, like Jai and Veeru, into the horizon of our collective imagination.

FAQs about Sholay (1975)

What is the release date of Sholay (1975)?

Sholay was released in India on 15 August 1975, coinciding with the country’s Independence Day.

Who are the main characters in Sholay?

The main characters include Jai (Amitabh Bachchan), Veeru (Dharmendra), Gabbar Singh (Amjad Khan), Thakur Baldev Singh (Sanjeev Kumar), Radha (Jaya Bhaduri), and Basanti (Hema Malini).

Where is Sholay available for streaming?

Sholay is currently available to stream in India on Amazon Prime Video. Streaming availability may vary depending on region and licensing.

![Dragged Across Concrete Review [2019]- Taste the Pavement](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/DAC_D27_04417-768x502.jpg)