The International Federation of Film Critics (FIPRESCI) released the following list around two weeks back. I will try and analyze these films briefly to work out an introduction to these famous works.

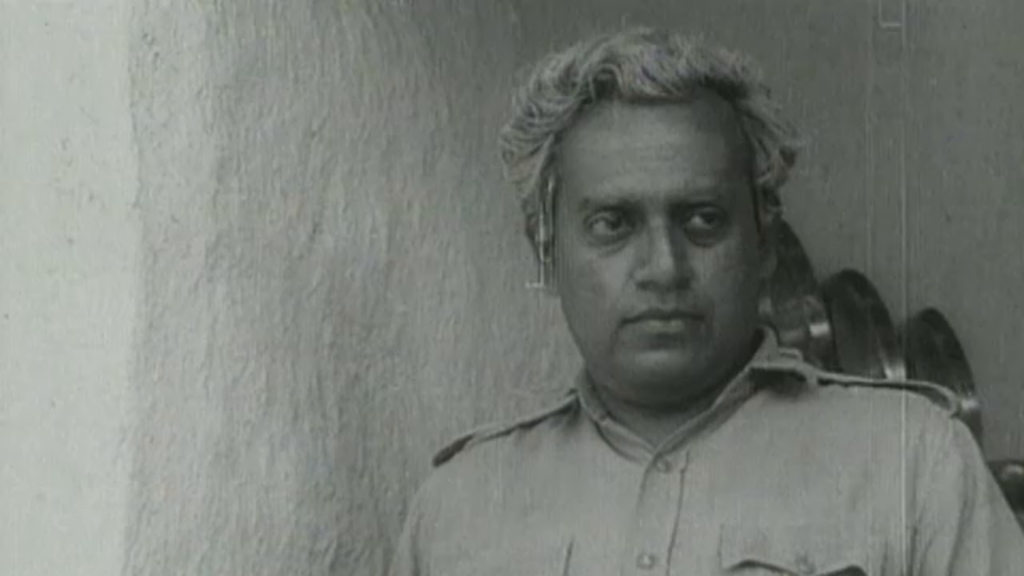

Pather Panchali By Satyajit Ray – Bengali

“I chose Pather Panchali for the qualities that made it a great book; its humanism; its lyricism; and its ring of truth. The script had to retain some of the rambling quality of the novel because that in itself contained a clue to the feel of authenticity; life in a poor Bengali village does ramble,” wrote Ray. Ray made two more films on Apu, the boy in Pather Panchali with Aparajito (1957) and Apur Sansar (1960) completing a trilogy he had not thought of when he made the first film. Contemporaneous with these films were two-three timeless films, Devi (“The Goddess”), Parash Pathar, and Jalsaghar (“The Music Room”). Pather Panchali (Song of the Road) was the celluloid adaptation of a classical masterpiece in Bengali literature by Bibhuti Bhushan Bandyopadhyay.

Pather Panchali (1955) was a historical necessity. Something had to burst upon Indian cinema like a wild wind, blowing away the cobwebs of the studio, the make-up on the stars, the filters on the camera lenses, and the painted canvas flats making up the walls in the studio huts. Suddenly, people looked like real people, dialogue sounded like real speech, houses looked like houses, children like children, and the back of an old woman, like the skin of an ancient crocodile. The relevant and the irrelevant, the ugly and the beautiful, the country flute and the foreign band brought the Indian village to life on screen. All of urban India, all of Indian cinema, was suddenly shocked to see reality reflect itself on screen. The making of this film brought him face to face with rural life, in its daily grind as well as in its inner rhythm that defied the pressures of poverty. He saw the life of the individual struggling against adversity, not the poor in the abstract as middle-class city dwellers usually do.

Yet, Pather Panchali is not a film about poverty but about hunger. It is a chronicle of life progressing from birth to adulthood through experiences common enough throughout the country beginning from medieval times right to the present day. Though it does depict hunger in different ways, each one is distinct from the other. It gives us a character like the doddering old aunt Indir Thakrun, portrayed by Chunibala Debi, a forgotten actress from the old theatre with an opium addiction discovered by Ray after a long search. In her eighties, the actress lent her own voice to the song in the film but passed away before the film was released.

The process of making a ‘real’ film that narrates a classic story, begins in the first film, fulfills itself in the third, Apur Sansar, and the second, Aparajito providing the bridge between the first and the third. The three films of the trilogy – Pather Panchali, Aparajito, and Apur Sansar were separately conceived, each to be seen by itself as an independent film, and yet to be seen as a cohesive whole of the story of one man – Apu – and his growth as well as the metamorphosis from a small child of four or six to an adult father returning to take his son on his sojourns across the country. The three films are bound by the same vision of the uniqueness of each human being, however ordinary or brilliant, and the perception of the morality that surrounds life even as it pulsates mysteriously in man, beast, and nature. It is this constant awareness of a larger framework that invests even the daily chores of life with a compelling significance in Ray’s films.

In Pather Panchali, Ray’s personal feeling was expressed from behind a curtain, as it were, of “objective” filmmaking. It suffused the story-telling but did not come out to the front. In the mother-and-son episode in Aparajito (1956), the feeling is much more personal, almost autobiographical. But Apur Sansar (1959) is possibly the most passionate film he ever made. He takes a classic outline of the poor, creative young man’s life, his marriage by accident, his very Indian flowering of love after marriage, the death of his wife in childbirth, his disenchantment with life thereafter, and his wanderings ending in the long-postponed reclamation of the son. Every stage is as familiar and typical as though it is taken from an epic, but is invested with feeling expressed through an infinite array of detail on the one hand and on the other, a sense of the cycle of birth, life, and death forever enacted on a planet turning in space. It is in this setting of detail against a larger sense of time and space that the memorability, the tension, and the resonance of the Ray image is created through his early films.

Pather Panchali is considered to be neo-realist in its implications. The main reason for describing the movie as neo-realistic was the fact that it was filmed not long after the II World War when neo-realism held sway in most of Europe. Satyajit Ray and Bimal Roy, two of the greatest filmmakers of India, were deeply influenced by Italian Neo-Realism in Cinema. Ray evolved to become one of the greatest filmmakers the world has ever produced. The influence of Italian Neo-Realism is said to have been mainly triggered within them through Bicycle Thief and through the films of Roberto Rossellini who came to India in the early Fifties.

Meghe Dhaka Tara by Ritwik Ghatak – Bengali

Three films, namely, Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Komal Gandhar (1961), and Subarnarekha (1962) dealt with the ravaged psyche of the victims of partitioned Bengal. The three together are regarded as a complex, trend-setting, cinematically splendid trilogy. Ghatak claimed that Meghe Dhaka Tara was “the greatest of all my films.” It is a corrosive, complex account of a refugee family with an incredibly stoic protagonist, Neeta. According to Ghatak, his ‘trilogy’ comprised of Meghe Dhaka Tara, Komal Gandharand Subarnarekha was his interpretation of the marriage of the two Bengals.

Meghe Dhaka Tara means “the cloud-capped star”. The title has layers of meaning and is open to several readings. Firstly, this is how Sanat described Neeta in a love letter he penned to her once. He compared her with a star that cannot hide its shine and sparkle behind clouds. Neeta hides this letter under her pillow. Shankar discovers this once by accident, when he steps into Neeta’s room. Secondly, the title relates to Neeta’s love for the hills. She reminisces in a conversation with Shankar how they had once gone to holiday on the hills as children. “We woke up while it was still dark to climb the mountain and see the sun rise. Imagine the pain when the sun did not rise that dawn,” she says.

Meghe Dhaka Tara paints a brutally frank picture in stark black and white images, of the family as a cannibalistic consumer of one of its own members. The ‘black and white’ does not refer to the cinematographic reality of the film. It is metaphorical and figurative in essence since the characters are painted in black and white. In fact, history points out that cinematographically, color had not become prolific in Indian cinema at the time the film was made. Neeta, her father and Shankar are the ‘white’ characters. Gita, Montu, and their mother are the ‘black’ ones. Sanat is somewhere in the middle of these two extremes, weak, spineless, indecisive, and in the ultimate analysis, as cannibalistic towards Neeta as the others.

Her courage is defined by her quiet submission and surrender to the wishes of the very people who consume her as fatally as her tuberculosis does. In fact, one is not very sure in the end about whether it is TB that takes her life or whether it is her family and her boyfriend who are responsible. The line between the family’s brutal cruelty towards her and the spread of tuberculosis within her body gets increasingly blurred as the narrative moves toward its dramatic climax. Her desperate cry, “Dada, I want to live,” underscores the family’s complete indifference to Neeta as a human being, leave alone its attitude towards her as a young woman who is the sole earning member of the family. The family as ‘consumer’ of the very member, Neeta, who holds it together marks the uniqueness of Ghatak’s presentation of decaying values in the impoverished scenario of the refugee family.

The telling use of fading editing enriches the film’s tapestry. The preference for close-ups, especially of the faces, highlights the contrasts. Shots of Gita are lit in a way that gives her a witch-like appearance. The lighting in the night-time interior shots adds to concentration and highlights focus. Ghatak has used the chhawra form of rhyme (Bengali version of folk nursery rhymes) twice to express the warmth in the relationship between Nita and Shankar.

Meghe Dhaka Tara remains a classic example of the power of sound in cinema. Ghatak used sound as an essential language of cinema, a tool of self-expression, an expression of rebellion, tragedy, and grief. His use of sound is not only aesthetic and imaginative but is also startling, designed to shock, to reach beyond the cinematographic frame of the film. In Sound in Film Ghatak gives an idea of the place of sound and how it can be effectively employed in the delineation of human relationships and the human condition. “We are so used to calling cinema a visual art that I sometimes fear we shall soon forget that sound has an important world of its own.”

Ghatak had a unique and perceptive vision that assimilated the searing spectacle of Partition, the black memory of refugee camps, the degradation of rootlessness, the dehumanization of the alienated, and the emerging definitions of a new class struggle. Ghatak externalized his private anguish into a global perspective. This heightened sensibility turned his art into a language that could be understood in distant Punjab and the rest of India, in Poland, Germany, Korea, Vietnam, Palestine, and any country that had been sundered by the trauma of separation and the bleeding scar of an overnight border.

Related List: All Ritwik Ghatak Films Ranked

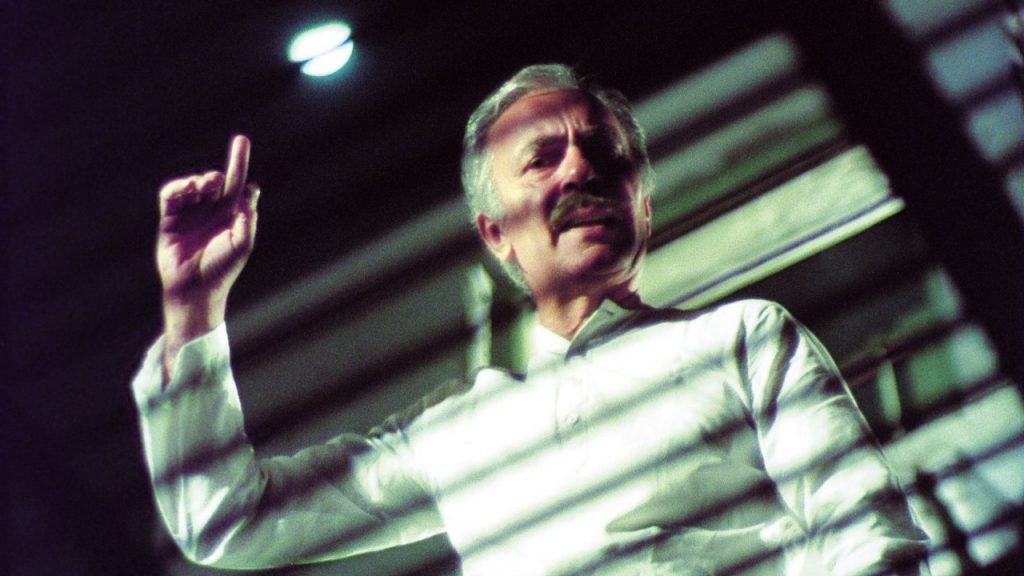

Bhuvan Shome by Mrinal Sen – Hindi

Bhuvan Shome was a path-breaking film in many ways, for Indian cinema in general and for Mrinal Sen as a filmmaker in particular. This was his ninth feature film but his first in Hindi. It was based on a novelette by Balai Chand Mukhopadhyay who was known better as Bonophool, a noted medical practitioner who was also a prolific creative writer of fiction. Many of his stories have been made into films but Bhuvan Shome stands out. Why? Because it is a very simple and straightforward story that Mrinal Sen narrates with interesting twists and turns in the technique of cinema such as animation, fast-forwards, close-ups, humor, and satire telescoping brilliantly into each other without the audience becoming conscious of it.

Bhuvan Shome is a bureaucrat who holds a high position in the Indian railways. He is a strict disciplinarian and not very popular among his subordinates for his insistence on honesty, integrity, and industry to sustain which, he did not spare his own son. But this basic honesty combined with a refusal to compromise also alienates him from everyone and also from his colleagues. But that does not deter him from his ideology. He is a widower and his staff is very alert because the news of his strict ways of handling corrupt people has reached them before he reaches his new office.

The camera uses the speeding railways tracks and the sound like a repeated metaphor signifying the mechanization of Shome through his routine-like existence manipulated by his dedication to discipline and honesty. Nature also plays a role in the metamorphosis of Shome when the camera pans across the sky to show a huge group of birds in flight, cranes/storks crowded on the shores of a beach, or, Shome running terribly scared through the dunes and trees escaping the wrath of the chasing bull, or, Gauri narrating the story of a king and queen who lived in a place now reduced to ruins and so on.

Vijay Raghav Rao’s beautiful music opens with a classical taan with the visuals focussed on the speeding railway tracks as the credits come up. The orchestra is comprised of cymbals, jal tarang, and an array of percussion instruments. Towards the end of the titles, the camera remains focussed on the tracks but is now silent because the narrator will take over and introduce Shome. The ambiance of music remains the same throughout the film while the visuals now shift alternately (i) between Bhuvan Shome and his interactions with the bullock cart puller (Sekhar Chatterjee) along the shaky roads of Saurashtra, (ii) between Bhuvan Shome and Gauri in her modest mud house and (iii) between Shome and Jadav Patel (Sadhu Meher) each exploring new spaces, new relationships with new negotiations in the life of Shome. The voice-over defines the honesty that underlines the “true Bengali” character of Bhuvan Shome by showing us glimpses of the “Bengali identity” through fleeting clips of Swami Vivekananda, Pandit Ravi Shankar, Satyajit Ray, and overhead shots of massive crowds defining the unrest of processions that describes Calcutta encapsulated in Bhuvan Shome. This intrusion is superfluous and does not lend itself to the spirit of the film at all.

The acting by the main cast, Utpal Dutt, Suhasini Mulay, Sekhar Chatterjee, and Sadhu Meher is organic and spontaneous as if they are not at all aware of a movie camera’s active presence on the scene. None of his theatrical backgrounds spilled over into his screen acting at any point. The complete caricaturing of the protagonist was not liked by some critics but looking back at the film as a whole, it did jell into the theme of honesty by investing it with a unique perspective blending comedy with satire. The tearing down of Patel’s dismissal order by Shome in front of Patel however, appears melodramatic considering the mood of the film.

Related Article: The Enduring Relevance of Mrinal Sen

Elippathayam by Adoor Gopalakrishnan – Malayalam

Elippathayam (The Rat Trap) is a 1981 Malayalam film written and directed by Adoor Gopalakrishnan. It stars KaramanaJanardanan Nair, Sharada, Jalaja, and Rajam K. Nair. The film documents the feudal life in Kerala at its twilight overshadowed with grief, and a sense of carelessness/avoidance as a form of revolt. The protagonist is disenfranchised and trapped within himself and does not want to – unable to change with the social changes taking place around him. The film premiered at the 1982 Cannes Film Festival. It was also screened at the London Film Festival where it won the Sutherland Trophy. It is widely regarded as one of the best Indian films ever made.

A middle-aged man, Unni, and his three sisters struggle as the feudal way of life becomes unviable in Kerala. Eventually, succumbing to the adverse conditions surrounding him Unni becomes helpless like a rat in a trap. The film’s name ‘rat trap’ is a metaphor for a state of oblivion to changes in the external world, such as the disintegration of the feudal system, in which some are caught and which leads to destruction.

The film is set in the now derelict manor house of an aristocratic family, that has obviously seen better days. The film begins by showing the audience about a rat problem, and Sridevi taking initiative to catch and drown them. Unni, the patriarch, in spite of the looming changes in the family’s fortune and the times, retains the old attitude and is portrayed as proud, and incapable of adjusting to the impending downfall of his family and remains oblivious to it.

The film revolves around Unni and is also driven by this character who is perhaps the most unconventional protagonist one has encountered in the history of Indian cinema. Even the ambiance he lives in – physical, mental, filial – defines him. His way of dressing, his very slow and lazy movements, and his clandestine peeping at the neighboring woman drying herself after a bath in the pond, offer detailed glimpses into the character realized with a goosebumps-raising performance by Karamana Janardanan Nair.

Unni is an escapist, a coward, and a narcissist whose entire life is divided between taking care of himself on the one hand and on the other, making his two sisters attend to all his cares including capturing rats who invade the home and even eat up into his ironed shirt. Sridevi, the younger sister, drowns them in the pond behind their home after catching them in the broken mousetrap she has repaired herself. The problem does not cease and Unni, who is afraid even of making eye contact, is scared stiff of everything and everyone, unperturbed because he knows his needs will be taken care of by his sisters. He is unconcerned when his sisters point out that their coconuts are being stolen. He feels physically attracted to a farm hand who tries her best to seduce him but he literally begins to walk fast in order to avoid her. She pokes fun at his cowardice.

Rat Trap, the title of the film, is not just about rats who invade the Unni home, as and when. The rat trap repaired carefully by Sridevi is not just a physical reality but is also a metaphor for the film itself. The large, dilapidated family home of the Unni family is a rat trap where one must either die or remain trapped or run berserk. Each member is captive within his/her own rat trap which Sridevi manages to escape from but Rajamma lives on to die or be drowned alive. Unni rises from the slushy pond, his hair dripping with water, water dripping off his clothes which suggests that he is doomed to live in the rat trap he has reduced his life and his home to.

The test of a great film lies in that each time one watches it, different layers of meaning begin to emerge that may not have been noticed in the earlier viewing. Ellipathayam is Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s third feature film and his first film in color. And it offers different readings at different viewings, especially when each successive viewing has a reasonably long time gap as one’s viewing also matures over time. Ellipathayam is an example of this experience where you notice things you may have overlooked in the earlier viewing. This critic has watched the film three times. The first time, I felt it was very slow but the story was powerful and the acting was brilliant. Ten years later, the second viewing made me aware of the social setting, the location, and the cinematography. The third viewing, another year on, added another dimension – the larger canvas of the time the film is placed in and the model lesson in minute detailing Adoor has worked on which added value to the earlier readings.

Related List: 10 Most Essential Films of Adoor Gopalakrishnan

Ghatashraddha by Girish Kasaravalli – Kannada

Ghatashraddha (The Ritual, Black & White, 1977) This was Girish Kasaravalli’s first feature film. The film won him the President’s Golden Lotus6 for Best Feature Film in 1978. The then 27-year-old became, and remains, the youngest film director to win a President’s Golden Lotus, at a time when Satyajit Ray, Adoor Gopal Krishnan, Mrinal Sen, and others were at the height of their film-making careers. The film carries the hallmark of a filmmaker who knew how to tell a story on film in his unique way, placing hard-hitting subjects in as subtle and as low-key a manner as possible.

Ghatashraddha launches a scathing attack on several social evils that dogged society during the period in which the story is placed. One of them is child marriage, an evil custom that victimized the girl child by marrying her off to a much older man. When the old man died, the girl was forced to lead the life of a widow filled with extreme forms of abstinence in the form of food, clothes, treatment, sex, and shelter. If she broke the virginity rule, like the child-widow then a teenager, Yamuna did without realizing the consequences of her “lover’ leaving her in the lurch, not only was she driven out of the village to live a life of extreme penury on the outskirts but was doubly humiliated as the father of the girl would perform her shraddha or death rituals using a pot (ghata) as a symbol to officially claim that she was “dead” to everyone and was, therefore an outcast. Most young girls who got pregnant or engaged in any affair as they turned young, would die of hunger, poverty, and socially structured negligence which amounted to inhumanity by one group of humans against a single child-woman.

Ironically, Udupa, Yamuna’s father who runs a pathshala in the village, not only performs the ghatashraddha but also gets married to a very young girl from the Brahmin community to “rescue” the girl from an unmarried status. This was a practice dominated and controlled by Brahmins driving home the point that Brahmin girls too, were not spared from barbaric treatment that often led to an untimely and tragic death comes across in the film. Strange, that this same Udupi had once saved his daughter’s life from snake-bite. And he is the one who not only agrees to perform the ghatashraddha of his living daughter but also throws her out of the village forever after having her head shaved completely.

There is a powerful subplot that merges into the main story. It is about a very soft and affectionate relationship that evolves between Yamuna and Nani a boy who joins the pathshala. Yamuna looks after him with motherly care. They develop a mutual bond, whereas other students like Shastry and Ganesh would harass her. The film set against a rural backdrop in Karnataka is placed sometime around the 1920s. Girish Kasaravalli himself wrote the script of the film during his training at the FTII. It is based on a Kannada short story by Dr. U.R. Ananthamurthy. B.V. Karanth scored the music and S. Ramachandra handled the cinematography. Meena Kuttappa as Yamuna and Master Ajit Kumar as Nani are in the lead roles.

Kasaravalli says, “It was a very powerful and extraordinary story. It spoke of rituals and traditions in Brahmin families. It was my first movie after I graduated from the Pune Film Institute. I selected Meena Kuttappa, who was a student at that time, for the role of Yamunakka. It won national (Golden Lotus) and state awards.” The best moment captured in the film is when, just before the climactic scene, the Shudra slave tells the main priest, “he saved his daughter even from snakes, but could not save her from a Brahmin” thus summarizing the tragedy of the Yamuna in one single sentence.

Garm Hava by M.S. Sathyu – Hindi and Urdu

M.S. Sathyu’s Garm Hava (1974) is the very first Hindi film on the Partition of India 25 years after the Partition happened. It has remained one of the immortal classics of the Partition of India. And it almost never got made and even after it was made, we might never have had the opportunity of watching it. M.S. Sathyu, who was by then known in theatre and film circles for his production design, and art direction, submitted a script to the Film Finance Corporation (which later became the National Film Development Corporation). The script submitted by him to the FFC was rejected, so he handed in another one—a story about a Muslim family that chooses to stay back in India after Partition in 1947 but gets uprooted from within in the process.

The story’s protagonist Salim Mirza is a Muslim shoemaker and patriarch who does not want to relocate to Pakistan. There is the added element of a love story woven into this political narrative which adds greater meaning to the story and takes it to its dramatic climax. The filmmaker’s imaginative creation of the use of light and framing added another dimension to the characters and their struggles. Salim is rendered helpless by the forces of this shift in attitude and in the sensitive and volatile political environment. But he stubbornly refuses to cross over to the other side because he considers India to be his home. It is one of the best films on how Partition victimized the minority in India and what impact it had on human lives, lifestyles, ideology, and economics.

The sad story is that the film’s release became a hurdle even before its release. The Mumbai office of the Central Board of Film Certification rejected the film, citing its potential to stir up communal trouble. Sathyu approached PM Indira Gandhi. Gandhi ordered the film to be released without any cuts. But even she could not ensure a smooth theatrical release. “N.N. Sippy took up the film’s distribution, but he backed out when we showed the film at a festival ahead of its release,” Sathyu says. “I eventually approached a friend in Karnataka who owned a distribution company and a chain of cinemas, and he released the film first in Bangalore.” Only then did other distributors step in to ensure that moviegoers saw for themselves the tragedy of a Muslim family that opts for India over Pakistan. The Shiv Sena rising in power at the time, wished to watch the film and this was followed by other vested political groups too. “We found that we were holding more private screenings for free for different groups than we could expect to earn from the ticket sales of the film,” said Sathyu in an interview.

That is not the end of the story. Even after the release and the accolades became to come in including the acclaim at Cannes and the string of national awards, the story of Garm Hawa was hardly over. The prints of the film simply vanished into thin air. No VHS tapes or DVDs were made—surfacing occasionally on Doordarshan. But all that finally changed when a privately funded restoration process put back the wheels of restoration of the classic film to recreate history. The rebirth of Garm Hawa is the result of passion, doggedness, and deep pockets. The process was started by Subhash Chheda, a Mumbai-based distributor who runs the DVD label Rudraa. Chheda approached Sathyu asking for permission to produce DVDs from the film’s negative. The negative had aged badly and was damaged in many places. The idea then took root of expanding the scope of the project—to re-release the film in theatres and re-introduce audiences to its sobering pleasures.

One distinctive feature of the film is that this is the last film to bring together members of IPTA and PWA together in the making of Garm Hawa both in front and behind the camera. Young and veteran actors from the IPTA came forth to act in the film from Delhi, Bombay, and Agra. Farookh Sheikh who played the younger son of the protagonist Saleem Mirza and made his debut with this film was a young actor with IPTA. A.K. Hangal who plays Saleem Mirza’s friend was of the IPTA and so was Shaukat Azmi. Sheikh, who was 24 at the time, was promised a remuneration of Rs.750 which he was finally paid in full 15 years later. Balraj Sahni, who portrayed the protagonist, was also a known Leftist and the only star of the film. He was paid the highest sum – Rs.5000. Writer Kaifi Azmi, of the PWA and IPTA, who wrote the dialogue, added to the screenplay his experiences of working with shoe-manufacturing workers in Kanpur. Everyone who mattered was known to be staunch leftists so they believed in the strong Leftist ideology of people’s faith in their homeland that came first and the belief that no one, of any faith or community, should be forced to leave the country if one wanted to stay back.

Garm Hawa was the first feature of M.S. Sathyu. It was the first film to deal with the human consequences resulting from the 1947 partition of India. This action, ordered by British Lord Mountbatten, split India into religious coalitions, with India remaining Hindi and the new country of Pakistan serving as a refuge for Muslims. Is ‘refuge’ the right word for Muslims who did not wish to leave? Would they be accepted socially and economically by the original residents of the newly formed Pakistan.

Charulata by Satyajit Ray – Bengali

Other than the Apu Trilogy, Charulata, perhaps, is the most hotly debated, variedly interpreted, widely discussed, and critically questioned among Satyajit Ray’s films. They continue to shed new light on the film. “Where Charulata herself is concerned, Ray achieves that wonderful transparency in the objective correlative which represents the height of cinema. Every thought in her mind is clearly visible, every feeling” writes Chidananda Dasgupta. He goes on: “Deeply intelligent, sensitive, outwardly graceful, self-composed and serene but inwardly the kind of traditional Indian woman of today whose inner seismograph catches the vibration waves reaching from outside into her seclusion, stirring her with a spiritual unrest.” Though one tends to agree with Dasgupta on most counts, one differs from his contention of ‘spiritual unrest.’ It is rather, an expression of sexual and emotional unrest.

Charulata (1964) is based on Nastaneer (The Broken Nest) a novelette of around 80 pages, written by Tagore in 1901. Its translator, Mary M. Lago, describes it as “one of Tagore’s best works of fiction.” The story of the film and the original literary piece takes place in 1879, at a time when the Bengal Rennaissance was almost at its peak. Western thoughts of freedom and individuality were just about to ruffle the age-old calm feathers of a feudal society. Thinking men were responding to it and some changes were already in motion. Women’s liberation was being talked about, but not much beyond a few cases of widow-remarriage and some education.

In Charu of Charulata, Ray probably discovered the crystallization of the Indian woman, poised between tradition and modernity. Intelligent, sensitive, graceful, and serene, Charu was a traditional woman whose psyche imbibed unto itself, waves from the world outside. It was changing, and below, in the drawing room, her British-influenced husband Bhupati was celebrating the victory of the Liberals in Britain. Nineteenth Century Western social philosophy and Ram Mohan Roy’s ideas were constantly working toward the liberation of women.

What gave Ray this deep insight into the mind of a woman who ‘lived’ at the turn of the 20th century and who fell in love with her husband’s cousin? She is the only one among the three characters – Bhupati, Amal, and herself, who has no crisis of conscience. Bhupati feels guilty for not having devoted enough time to her and blames himself more than others for his predicament. Amal realizes that he was about to betray his cousin’s faith in him and runs away. It is Charu alone who does not turn away from her passion. In her reconciliation with her husband, there is no sense of guilt. Nor is there any arrogance or pride. All that is left is the recognition of reality.

Charu switches over from the embroidery frame to the lorgnette, to a pack of cards or the paan-box to writing for a magazine. Charu peeping out from behind the bedpost at Amal when Bhupati is unfolding the story of the theft to Amal; Charu swinging away to daydream and to discover a subject to write on; Charu unrolling the straw mat out in the garden; Charu crumbling up pieces of paper of her ‘rough’ work and throwing these away; Charu hitting Amal with the magazine her article is published in; Charu reprimanding Mandakini for small lapses are tiny details that are complete in themselves, yet weave out to form a single ‘theme’ reflecting Charu’s exploration, creation, transcending of objects that surround her and objects she possesses and uses that mean much more than their physical reality implies.

Charu’s radical stance is comprised in that she is conscious of her transcending the moral and social spaces sanctioned by marriage by falling in love with Amal, a relative by marriage, younger than she is. But she does not shy away from expressing it. She does not care if the rest of the family, except Bhupati notices this. Amal runs away from any possible contravention of the norms of conventional morality. Her total obliviousness to her husband’s dilemma distances Amal from her. The camerawork in the film is caressingly soft, blurring the blackness of Black while taking care to soften the whiteness of White, in keeping with the grayness of the characters within the film. Charu of Charulata, therefore, stands out as the finest blend of the ideal and the pragmatic, the radical and the traditional, among all of Ray’s women. Tagore’s Charu is a woman ‘born’ much ahead of her time. Ray’s Charu reasserts this literary ‘reality’ ages after Tagore created her in Nastaneer. If Tagore gave life to Charu, Ray added meaning to it.

Ankur by Shyam Benegal – Hindi

His first feature film in Hindi, Ankur (The Seedling, 1973), tells the story of an arrogant urban youth who returns to his ancestral home in feudal Andhra Pradesh. His subsequent affair with the wife of one of his laborers (played powerfully by Shabhana Azmi in her debut) and her eventual call to arms against the feudal system brought him criticism for using a purportedly “un-Indian” approach and for “victimizing” women. The film brought the problem of feudal and patriarchal structures to the fore.

Ankur is set in Andhra Pradesh in South India and uses the local Hindi dialect with a thick accent picked up from the regional lingo. Based on his own story, Ankur (Seedling) unfolds the story of a zamindar’s son, Surya, who arrives from the city to oversee his father’s estate. Bored and sexually frustrated, he seduces his attractive maidservant (Shabana Azmi), the wife of a deaf-mute Dalit laborer (Sadhu Meher.) The arrival of his wife, who senses her husband’s involvement, and the discovery of the maidservant’s pregnancy brings the situation to a head.

Surya, as his way of escaping the maid’s anger and/or retribution, leashes the deaf-mute husband who is ecstatic on learning of his wife’s conception, the truth veiled by his naiveté and innocence. Though in sum, the affair clearly implies adultery on the part of the maid, it is a power game where the employer abuses his power over his victim first, by seducing her and involving her in an adulterous relationship (he is married too), second, by impregnating her, and finally, by disowning her and taking out his frustrations on the low-caste, deaf-mute husband of the maid. In a sub-theme, Benegal shows that the young man’s father, the zamindar himself has a kept woman who has borne children by him. But he is fairer to the woman than is his city-bred son towards the woman he seduced.

The film launches a three-pronged attack through the film. One is about the seduction of a young woman, who works as a maid in the zamindar’s son’s house. It is not rape but it is a seduction that leads to consent on the part of the young wife of the Dalit man who works on their farm. There is a clear power relationship between the two. The second is that the couple – the wife (Shabana Azmi) and her husband (Sadhu Meher) are Dalits and therefore, right down the ladder of the caste hierarchy. The third is that this husband is also a deaf-mute so he has no voice – socially and physically.

The silence of the deaf-mute husband, therefore, can be defined as a political statement on the oppressed, the marginalized, the poor, and the outcast, which includes women. Silence in this sense is an explosive expression of resistance, revolt, suppressed anger, and rebellion, which finds eloquence because of its juxtaposition against all the sounds that characterize the normal sound film. Its dramatic impact is part of the director’s total design for the entire film. The culture-specificity lies in the significant revelation that almost without exception, it is the marginalized that recede into this shell of self-imposed silence, either for the entire film or for part of its narrative footage. Benegal, through the deaf-mute husband in Ankur, unwittingly surrenders or designedly structures this inheritance to the past history of Indian cinema. The silence within the man is biological, coinciding with his other marginalities – being a hired peasant, and a husband whose wife has been seduced by the same landlord’s son, thus adding to his subaltern position within the framework of his family, his caste, his village, and the society and the time he belongs to. The oppression of native colonialism thereby, directly from within the characters of the film and indirectly from the urban audience, flows from the film to the viewers and vice versa.

Related List: 10 Best Films of Shyam Benegal

Pyaasa by Guru Dutt – Hindi

Pyaasa (1957) is the first of Guru Dutt’s masterpieces and the first of his tragic trilogy comprised of Pyaasa, Kagaz Ke Phool (1959), and Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962.) Pyaasa is a romantic melodrama set in Calcutta that explores, through the sojourns of Vijay, a man’s thirst for love, thirst for recognition and thirst for spiritual fulfillment. Vijay is fascinated by the very act of collecting material for his poems focussed on India as a nation-state. Rejected by his family and society, Vijay is a poet who nobody wants to publish. He is forced out of his house by his two brothers who accused him of living off them like a parasite without the slightest intention of taking up a regular nine-to-five job. They mock the idle poet who roams the streets and by-lanes of the city looking for poems, words, and images instead of seeking gainful employment.

His sweetheart Meena opts out in favor of marriage to a successful publisher. Once out of his house, Vijay keeps wandering aimlessly, as if in free space, but mostly confined to the marginal fringes of the city normally considered taboo for the kind of social strata he comes from. He wanders through the nocturnal spaces of beggars and prostitutes. In Pyaasa, Vijay always remains poor, but his poverty feeds his art and provides him with the appropriate material for voicing the concerns of the subordinate and the marginalized. He becomes a poet of the poor. Yet, when he finds that his poetry is lining the pockets of his exploiters, he renounces himself as the author of his poems. His becoming poor, in the Hindu sense, is in essence, a rejection of materialism When the film’s audience is busy throwing him out of the reception hall, the auditorium audience, applauding Vijay, is ready to welcome him into their midst.

Guru Dutt had originally kept the end tragic but later, at the suggestion of his distributors, he changed the end to a more acceptable one. Another striking element in the film is the characterization of the two women, Meena, Vijay’s girlfriend who ditches him for financial security, and Gulab, the prostitute who buys back his poems from the shop where they were already sold. They offer sharply defined counterpoints to each other, probably by intent and though this intensifies the melodrama, it does not strip the film of its essential statement. Gulab has often been drawn as an extension of Chandramukhi of Devdas, a prostitute who denounced his vocation after she met and fell in love with Devdas. But Vijay in spite of his partly circumstantial and partly willing alienation from mainstream society finds peace in an alternative world peopled with the likes of Gulab. He offers a positive counterpoint to the extremely negative and pessimistic image of Devdas.

Gulabo (Waheeda Rehman) of Pyaasa is perhaps the most restrained and dignified prostitute in the history of Indian cinema. Her dignity is subtle and underplayed probably because she is very poor. Her love for the poet Vijay (Guru Dutt) is rooted in the fact that when they meet for the first time, both share common social and physical space – the fringes of civil society and the margins of poverty. The irony of her character lies in that she loves poetry and at a point of time, even decides to publish Vijay’s poems at her own expense in the form of a book. She buys the file of Vijay’s poems his brothers had sold off to a shop trading in old newspapers. She approaches Meena (Mala Sinha), Vijay’s old flame now married to a very successful publisher, with a request to get the poems published. When Meena tries to buy them off, she gracefully declines, quietly ignoring the cruel barb Meena makes hinting at her profession.

The fact that Vijay’s roots lie within the framework of so-called middle-class respectability does not intrude into the undercurrents of bonding that draw them close on emotional terms, though Vijay realizes her worth only at the end of the film. When counter pointed against Gulabo however, Vijay comes across as selfish and self-centred. Till the very end, he remains unaware of Gulabo’s secret yearning and love for him. It is only after the bourgeois society rejects him completely that he realizes that the only person who can offer him true and selfless love is Gulabo who is a social outcast, an outsider by virtue of the fact that she inhabits a world where her means of survival is to sell sex beyond the borders of the very bourgeois society that has rejected him.

Sholay by Ramesh Sippy – Hindi

Ramesh Sippy’s all-time hit Sholay (1975) is perhaps the most-reviewed film in Hindi mainstream cinema. But few critics have ever explored the possibility of reading it as a road movie. Probably because the storyline had different layers – revenge, love, hate, bonding, pride, solidarity, integrity, courage, greed, fun, happiness, and so on. Sholay is such an all-encompassing film covering every kind of human emotion that one completely misses out on pointing out the rootlessness, the sense of casual adventure, the bonhomie and the essential loneliness of the two small-time thieves Veeru and Jai. Till Veeru and Jai reach Ramgarh to take on the assignment Thakur has for them, they are constantly on the move. When their pockets are empty and they must settle down before the next action, they get themselves caught by the police and take some respite in prison. Veeru and Jai are thieves. But they are good-natured, simple, bold, strong and extremely likeable souls.

The two have neither home, nor family, nor any roots to hold on to. They are not given any social history. Nor does one notice any desire in them to get rooted and settle down in one place. They appear to be quite content with their lives in a constant state of flux, geographically and financially.

The film opens with the two friends singing yeh dosti hum nahin bhoolenge on a funny motor bike with a flexible carrier that moves away and comes back to join the main vehicle during the song. As the film moves in flashback, we find them inside a moving train where they meet the much-younger Baldev Singh Thakur for the first time when he is a police officer.

Sholay is not only a road movie but it is also a journey film. The difference between the road movie and the journey film lies in the strong and concrete physicality of the former and the abstract, conceptual and sometimes, ideological themes that dot the latter. Destination, be it a journey or be it the road, is uncertain, undefined and sometimes infinite, reminding one of destiny which makes one’s destination ambivalent.

When they meet Baldev Singh Tahkur again years later at Ramgarh, his hair has turned white but Veeru and Jai remain as young as they were when the film began. Thakur’s hair has turned white before time probably because of the shock of losing his entire family except the younger bahu shot down in cold blood by Gabbar Singh. Veeru and Jai’s rootlessness and living away from the mainstream appears to have stopped the ageing process for them.

The two metaphors of wanting to belong, wanting to be loved, are expressed when Veeru says he wants to get out of thieving, marry, and have a train of kids. Jai’s mouth organ, a small musical instrument that can travel with its owner everywhere, is a symbol of his desire to be loved and to belong. Every night, he sits outside his outhouse in the Thakur’s mansion and plays on the mouth organ, waiting for Radha, the widowed young daughter-in-law to come out on the balcony. The tune he plays is the same everyday, because that is probably the only tune he knows to play. It is a sad, melancholic tune that reflects the sadness of his life and underliines the pathos in the solemn and silent face of the widow. It is also a silent pointer to the tragic end of this love story. When the film ends, it is inside a train where Basanti, the tongewalli, is waiting to go away with Veeru to begin a new life together. Will they settle down to domesticity? Or will they embark on a different journey with a different destination? The film keeps the question hanging in the air.

The modes of transport also describe the different journeys of the other characters. The film has a funny motor cycle Veeru and Jai are riding in that indicates their bonding and also hints at their separation in the end. There is the train which Gabbar Singh’s dacoits want to loot which is thwarted by the young police officer Thakur Baldev Singh. Gabbar Singh’s gang are on horseback and that is their vehicle of transport. For Basanti, it is Dhanno and the tonga he pulls that is not only a way of life for her but also a friend, a guide and a helper. Ahmed rides a yearling.

It is Gabbar alone who does not move much from the den that is his place of operation and perhaps, also, his home. It is not a cave but an open hillock he presides over like a lord, swinging his leather belt this way and that, chewing tobacco from his small pouch and spitting it out. He makes his men do all the riding and lootingas he is confident that he holds even distant villages in a constant ambience of fear. He is bothered neither about a journey nor about a destination. He has a one-track mind – holding people in terror and fear and looting them on demand.

The sub-texts are also interwoven with journeys. One journey is the one the young Ahmed takes on the back of a yearling (young one of a horse) making his way to a job opening in the city. It turns out to be a journey of no return when the yearling trots back to Ramgarh slowly without its rider. Basanti running away in her tonga pleading with Dhanno to take care of her ijjat when Gabbar’s men are on a hot chase is another action-filled journey. The flashbacks into Thakur’s past and the past of the two good-hearted thieves are stranded together with journeys across time and space with the train and the railway tracks as a repeated metaphor. There is a beautifully shot and edited scene of men on horseback running parallel to the running train when the dacoits and the police are pitted against each other.

Basanti’s tonga is a motif of Basanti’s unusual characterization. The trotting sounds of Dhanno, the horse, pulling the tonga with Basanti wielding the whip cut into with the sounds of the bells in Dhanno’s neck is a sound metaphor. She is a strong young woman, courageous enough to carry male passengers from the nearest station to the village and back. Radha, Thakur Baldev Singh’s widowed daughter-in-law, charts a journey from being a very bubbly and jabbering young girl fond of Holi to a shy young bride to a widow swathed not only in widow’s weeds but also in silence. The journey is also from speech to silence.

Sholay offers a textbook model for a road movie because it has four basic elements – the road, the journey, the destination and the characters undertaking the journey. In Sholay, the ‘road’ per se, may be absent and the character/s who undertake/s the journey define/s it as a ‘road’ movie. The characters are the most important while the road and the journey are secondary to the character. What better example can one find but in Sholay?

Similar List:

25 Best Malayalam Movies of All Time

Announcement: High on Films is now on YouTube as well. Watch our videos and subscribe if you like our work.