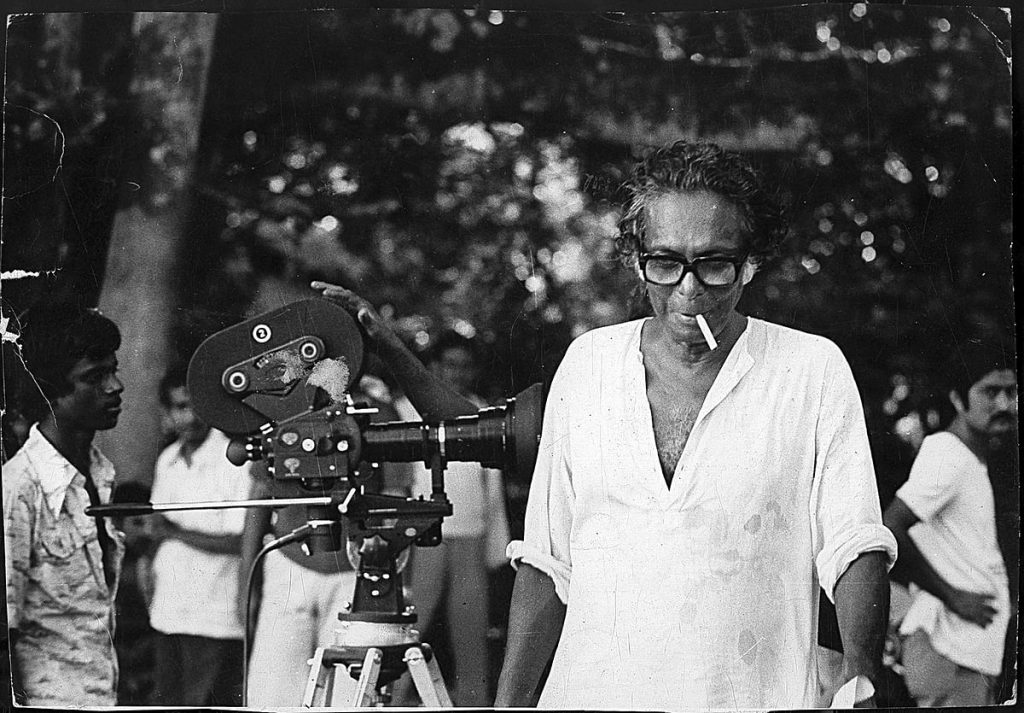

My introduction to the works of Mrinal Sen occurred late. Unlike the movies of Ray and Ghatak that I had grown up watching and revisiting, I started watching Sen’s movies like an ingenue. Often cited alongside his contemporaries Ray and Ghatak as one of Indian Cinema’s trinity of legends, Sen’s films have a consistently radical approach towards filmmaking.

Coincidentally, a film that I chanced to see on his 97th birthday on 14th May, was his multiple national award-winning Akaler Sandhane (In Search of a Famine, 1980). And for more reasons than one, this felt like a revelation.

A film about a film, it is about a director and his crew who go to a village to shoot a film on the great Bengal Famine of 1943. During their stay in the village for a month at a dilapidated house that was formerly a zamindar’s palace, they discover that there is no need to go in ‘search’ of the famine – it is an ever-present reality in the villages of Bengal. Released 40 years ago, it is still as relevant in contemporary times, even more so within the context of the pandemic.

It is a striking reminder of how crises like the famine in 1943, or that of the present pandemic to stress about, affect lives differently based on their social position. With migrant workers in the country dying on the road of hunger, the incidents cut clear through the senses of an economically divided society far removed from the daily realities of its fellow countrymen.

Starring Dhritiman Chatterji, Deepankar De, Smita Patil and Sreela Majumdar in pivotal roles, Sen’s film blurs the borders between the past and present, constantly merging the filming sequences of the crew to the reality of the villagers.

Smita Patil plays the role of Sabitri in the film-within-the-film where she lives with her destitute husband and new-born, starving for days. Helpless, she spends one evening with a contractor from Calcutta and brings home rice and kerosene oil – essentials that have long vanished from the market.

Her husband realizes this and rages, breaking all the utensils in the kitchen, and just as he is about to dash the baby to the ground Sabitri screams and stops him. This reel sequence is broken with the shriek of Durga (Sreela Majumdar), a local villager whose reality coincides with that of Sabitri. What is common to both the reel and real – whether they are set in rural Bengal of 1980 or that of 1943– is still poverty and hunger.

Sen’s vision grows out if this coinciding with filmic characteristics to make another relation palpable. The parallel not just between the past and the present, but also about art and reality and the limits of representation.

How far can an artistic medium like cinema create to portray the truth of reality? In the end, the film unit has to pack up and leave for Calcutta, forced to shoot the rest of the film in the studios. What haunts the viewer, however, is not the fate of the conscientious director’s film, but the fate of Durga in the village.

Sen’s film ends with a still of Durga, rapidly receding in the background, with a voiceover ending her tale in three lines: “Durga is alone. Her infant died. Her husband cannot be found.” The search for the famine remains incomplete in its rendition.

Now, that we are in the middle of a pandemic, with thousands of people dying, and without a possible certainty of normalcy. The horrors of the present are slowly overpowering the art forms and will certainly persist.

Where does a film like Akaler Sandhane stand in the response generated by COVID-19 that evokes many popular dystopian or post-apocalyptic books and movies? It is certainly not in the line of Virus (2018) or Contagion (2011)- fictionalized representations of a pandemic that are too real at the present. But, these two examples are similar to Akaler Sandhane in the sense that all three of them remind us that the social and cultural boundaries we use to structure society are fragile and porous, not stable and impermeable.

They partly illuminate the fears of invasion and the perceived threat of outsiders that can diminish our humanity. The fear and resultant apathy for the film crew, looked as ‘outsiders’ by the end of Akaler Sandhane is the testimony to the ingrained fear for outsiders.

But Akaler Sandhane stands out from the other models of cinematic treatment of a crisis because it provides not just a representation, but a response. Sen’s film takes a further step ahead since it can provide an example, and a succinct glimpse, for understanding the cultural response to COVID-19 shortly. Even more dreadful than the famine that Sen’s film depicts, is the cultural response to the pandemic which is still rooted in a certainty that narratives can lead to discriminatory behavior or racism.

Now neither is Mrinal Sen a subjective filmmaker nor is his film in question. And I am not, for once, comparing this film with the frenzied present, but the sequences of the film at once feel eminently relatable at times like these. His words- “In a way, we are exploiting the situation. We cannot do anything about poverty, by making a film, we cannot do anything to the economic structure of society,” instantly strike a chord with the helplessness that I as a middle-class citizen of this country feel.

This takes me back to the introduction where I had recognized my late entry into the world of Sen. This subjective example is but a reminder as to how modern cinephilia worships Ray, salutes Ghatak but seldom remembers the genius of Mrinal Sen.

Probably, a contemporary filmmaker like Kaushik Ganguly sums this up correctly. He said, “Today, we need to take stock of the way this man consistently went against the tide to pave way for future storytellers. Kharij and Akaler Sandhane are just as valid today. They speak of our hypocrisies and fears, but also about the emotions that redeem us. These emotions are timeless, as are the storytellers who can capture them honestly.”

Like Akaler Sandhane, Mrinal Sen remained out of bounds for narrative cinema, on the outskirts of the popular convention. Through this film, he wanted to study characters and situations through a socio-political lens — interrogating their responses, moral dilemmas, self-corruption, and exploitation, which can then provoke the spectator to start a discussion. In the end, it is this invitation to discuss that we must not decline.

More Articles Related To Mrinal Sen:

Mahanagar (1963): Uncertainties Meet Expectations

Cat Sticks (2019): A Black And White Exercise In Excellence

Abyakto (2019): About Unexpressed Nuances of Life

Bird of Dusk (2018): A Celebratory Look Onto Rituparno’s Reality