Guillermo del Toro has always had a remarkable talent for evoking emotion from the grotesque. His oeuvre, including ”Pan’s Labyrinth,” “Crimson Peak,” “The Shape of Water,” “The Cabinet of Curiosities,” always touches a soft, aching human core. His adaptation of Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” (2025) carries a similar sensibility.

But here, he turns the story into something more personal. Instead of retelling Mary Shelley’s novel to the letter, he shapes it into a reflection of human emotions—grief, longing, jealousy, and loneliness. The narrative emphasises how the human psyche is like a sapling. Its fruit varies upon the soil and nourishment. The plot waltzes around, touching and exploring the phenomena of human emotions.

One of the most unsettling elements in the film is how Victor’s mother, Claire (Mia Goth), mirrors his sister-in-law, Elizabeth (yes, also Mia Goth!). The director has cast the same actress to play two different characters, who are not even related by blood. Their physical resemblance is obvious, but what stays with the audience is the repetition of their inner lives.

On one hand, we witness Claire’s married relationship only in fragments. Charles(Charles Dance) is almost always absent, lost in his work, while Claire leans heavily on Victor( Oscar Isaac) for affection and company. There is loneliness in her eyes, which is exhibited through the family portrait. Painter Arthur Gain has wonderfully drawn from Goya, Sir Thomas Lawrence, and Gainsborough.

On the other hand, Elizabeth’s frustration is voiced more directly. While watching a beautiful butterfly trapped inside a glass container, she calls it “entirely bewitching,” but is unable to choose anything for herself. Both women, in different ways, live like that butterfly—decorative, admired, but confined. Yet Elizabeth has one small divergence from Claire.

Before she dies, she admits that she found a strange fullness in her brief encounter with the Creature (Jacob Elordi). Like a drop of crimson on her white wedding dress, this confession of love sets her free. We see her unveiling herself willingly in front of the Creature, whereas Claire was seen in a veil in front of Charles.

But the Creature cannot be understood without Victor, and Victor’s wounds cannot be separated from Charles. This three-way entwined angle of resentment and longing forms the film’s emotional layout. Victor grows up desiring a father who is fully present. Instead, he sees Charles only as a distant, successful figure—someone to compete with, someone he blames for his mother’s death, and someone whose approval he craves but never receives.

His vow to learn “more” is not the pure pursuit of knowledge. It is the desire to surpass Charles, to be stronger, cleverer, even godlike. There can be a Freudian reading of this behaviour. According to Freud, the child seeks emotional closeness and reassurance from its mother. And the Father becomes recognised as a separate and powerful figure.

The same goes for Victor and Charles. Claire’s death provoked this rivalry more. This Oedipal characteristic makes Charles a competitor and an inspiration for Victor. I felt this was the main reason why Victor was attracted to Elizabeth, the doppleganger of his mother. When Victor creates the Creature, he momentarily oscillates between the roles of a mother and God. He gives life, but refuses responsibility for it. Charles once placed the burden of family pride upon Victor, and Victor repeats that cruelty by refusing to give the creature the dignity of a name.

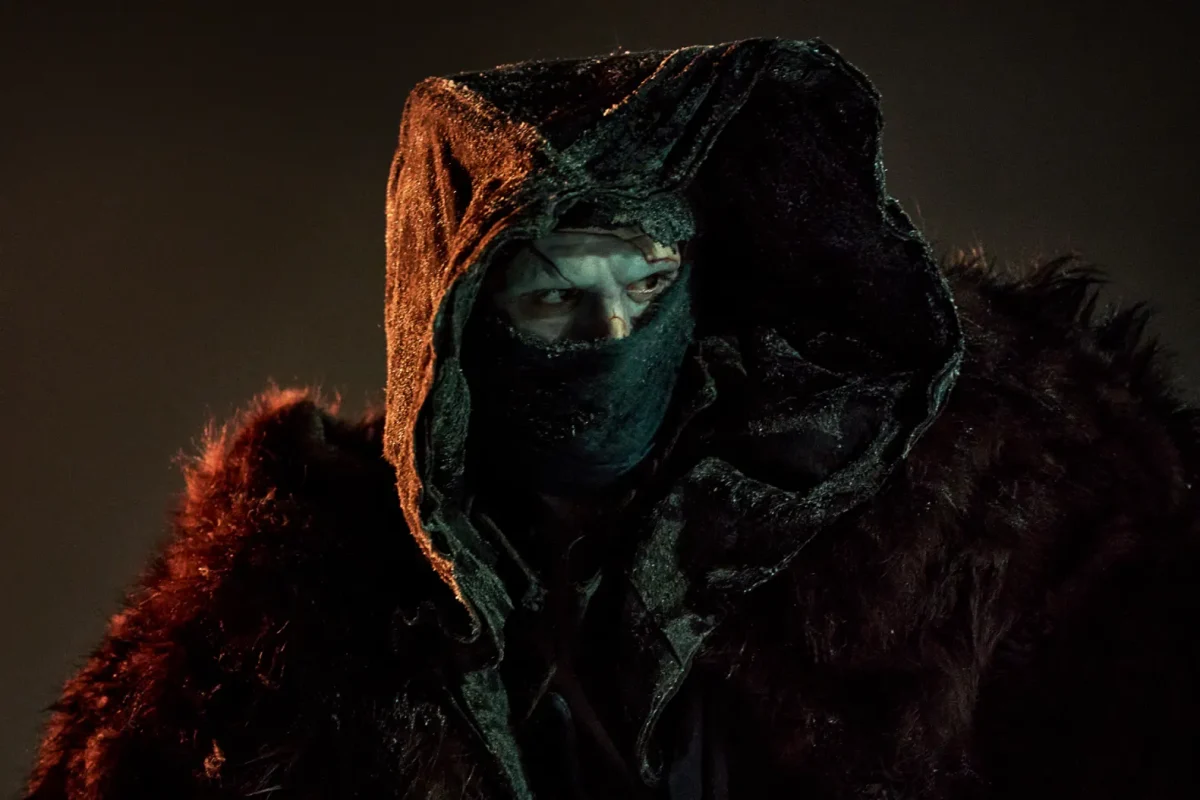

Namelessness in Del Toro settles like a wound. The Creature carries it in his spine, the way the body preserves certain injuries without needing to announce them. He had no template for the sound “father,” no internal theatre built to rehearse that idea, which is why the blind man’s tenderness, his unselfconscious acts of care, translate into friendship.

Fatherhood demands a past that the Creature was never given. Friendship thrives in the immediacy of shared air. Del Toro describes the Creature with an “eternal note of sadness,” a register that exceeds the body’s ability to repair. This is the same tonality Sophocles imagined over the Aegean — sorrow that hums behind identity, older than the hero, louder than exile.

When the Creature finally inspects himself through revelation rather than reflection, he names what he finds without adornment: born in a charnel house, assembled from the debris of the unclaimed dead, resurrected without provenance, engineered without kin. A body animated by collisions and discard, a life that arrived without foreword. His regeneration behaves like biology — efficient, automatic, unceremonious. His loneliness refuses biology’s triage. It stays intact, unrevised, unprocessed, a constant hum beneath repair.

The film resembles the story of the Cumaean Sibyl, who was blessed with long life but not eternal youth, trapped in a body she no longer desired. Similarly, the Creature is trapped in an existence that is stitched into an abysmal reality. The lines from “Bhaja Govindam” –“Who is your wife? Who is your son? From where have you come?”—ponder over the Creature’s wandering like a question he cannot answer. He has no past, no relationships, no origin he can claim.

What is most striking is how childlike he is at first. His only word is “Victor,” spoken with the desperation of someone looking for the one connection he believes he has. He follows an elk in the forest and tries to befriend it, only to see a man shoot it a few moments later. The so-called monster shows gentleness, whereas the human shows violence.

The violence between nature and humans seemed inevitable to him. He realised that with a single step, he had stepped into a world where people are hated for what they are. Del Toro repeats this contrast when the Creature walks across an abandoned battlefield. A newborn life walking through the wreckage of other men’s decisions—two creations, both are of men. The futility of war and the destruction it brings call attention to the innocence of a new life.

The plot metamorphoses from a question of identity—Who is the Creature?– to the more intricate problem of acceptance—What does he do with the self he discovers? Instead of offering an easy answer, Del Toro allows the Creature a slice of freedom. In the denouement, his final walk into the sunset feels neither triumphant nor is it tragic. It is simply open-ended, as if he is stepping into a life where he might find a way of fulfilment.

The symbols throughout the film—stitched skin, broken bodies, trapped insects, cold rooms, and the haunting emptiness after healing—point to a single idea: we inherit more from the people around us than we realise. Victor inherits rivalry and grief. Claire breathes her last with disappointment. The Creature inherits a life without death, and a life without death is a carcass of life. Victor wasn’t lucky enough to get a closure from his father. But on his deathbed, he reveals how regretful he was as he left the monster stranded. It is not until they forgive each other enough to surrender to their reality.

Del Toro’s “Frankenstein” argues that monstrosity does not come from deformity or fearsome strength. It sprouts out of abandonment, misplaced affection, and emotional wounds that are never mended enough to heal. What we call a monster may simply be a being shaped by misunderstood love.

It shows how one individual’s appearance can be deceiving. Heinrich Harlander (Christoph Waltz) appeared to be a gentleman, but his festering self was hiding beneath his wig and dress. He was dying of syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease. This gives us a peek into his clandestine life, and his wish to be immortalised inside the creature shows his incessant yearning or greed for power and life.

In the end, del Toro transforms Shelley’s story into a profoundly devastating meditation on human fragility. Elizabeth’s green evokes life and vulnerability, while Victor’s red underscores obsession and destructive intensity, showing how passion and mortality collide. The narrative captures how dependent we are on tenderness, and how easily one person’s loneliness becomes another person’s inheritance with perfection. Del Toro’s “Frankenstein” is a story about longing, about the ache of being unclaimed. It talks about the journey and survival before one realizes “from dust you came and to dust you return”.

![Our Friend [2021] Review: A Predictable Story Elevated by Terrific Performances](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/our-friend2-768x427.jpg)